'Wicked' Is the Film We All Need Right Now

Let’s talk about how the big screen improves the musical’s political messaging (and why it's the perfect film to go see after the U.S. election)

There is a moment in Wicked: Part I, the big-screen adaptation of the Wicked stage musical, where my cynicism – hardened to tungsten strength by the U.S. election this past month – melted away and, if only for a moment, I remembered what it felt like to believe human beings can be better than they are. By the end of the film…well, I’m not saying my faith in humanity was completely restored, but sweet baby Jesus riding a broomstick, it did restore my faith in the power of Hollywood to produce films that genuinely stand a chance of challenging people and changing them for the better.

Before I get to the moment, I want to say what you’re about to read is not a review. I don’t write film reviews here at 5AM StoryTalk. But it’s also maybe, fine, okay, whatever, kind of a review? Because as I write this, I’ve only been out of the theater for ninety minutes and I already want to go right back to see it again.

Wicked: Part I left me elevated. It’s left me hopeful. And I swear to Zeus and Baby Buddha and the Guardians of the Galaxy, it’s the film anyone feeling broken, beaten down, defeated – ready to throw in the towel on anything or everything – needs to go see, like, right now. In fact, I don’t even want you to read this article if you haven’t seen it yet (which is going to veer hard into storytelling as all of my writing here does). Just grab your coat and go; I’ll be here when you get back, don’t worry.

[Patiently twiddling my thumbs while you go see Wicked: Part I.]

Ah, you’re back. Obviously, you won’t mind all the spoilers to come now. So, out with it — what did you think?

Yeah, I have notes, too, and I’m never going to get comfortable with how weird and unreal everything in these CGI fests feels, but come on – come on! – that finale, where Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) grabs the broom and leaps through the window all action hero-like and, you know, does her thing and then flies around the sky before singing, “So if you care to find me, look to the western skies”? I’m not saying I literally cheered, but, yes, I literally cheered. It’s okay, though, because the two women on either side of me were crying happy tears because they’d waited twenty years to see this 2005 musical on the big screen and it clearly delivered for them, too.

Okay, about the moment I realized I loved this film—

No, wait, maybe not yet.

You need context first.

You need to understand how truly cynical I’ve become, how bitter, how angry. Maybe you’ve come to this place in your life, too. The 21st century has not been kind in so many ways.

I hate how I feel about the world most days, but most days the world also justifies that rage. I’ve developed tools to counteract my darker tendencies – I’ve discussed some of them here at 5AM StoryTalk – and yet the darkness never goes wholly away. It vibrates right there at the edge of my consciousness, like one of Hans Zimmer’s more experimental scores, both discomforting and as demanding as a siren’s call - “Give in, give up, fuuuuuuuck itttttttttttttt.”

This is why I think I groaned when I saw the trailer for Wicked.

Through no fault of its own, this film simply arrived in my life at a point where I didn’t have any energy left for what it wanted to offer the world — or rather the trolls, media personalities, and politicians it would inevitably incite.

It’s not that the Far Right wasn’t always going to react negatively to Wicked: Part I, mind you. The musical is deeply political, too; at the time of its premiere, many critics panned it for being too preachy about its messaging. Its inspiration, the novels of L. Frank Baum, were equally progressive.

Oz has always had something to say about the concerning state of the world — including race and fascism — is my point.

But Wicked: Part I manages to deliver its message louder and more effectively than the rest put together while simultaneously changing very little about its own musical source material. One major reason is the re-election of Donald Trump, which somehow makes the film’s message even more relevant and imbues several aspects of its story with new, deeper meaning. More on that later.

First, I need to tell you about the moment, the emotionally transformative one I’ve been building up to. Though maybe I should point out it’s not even the first time I wept watching the film. That privilege goes to a scene in which Elphaba’s sister Nessarose (Marissa Bode), who uses a wheelchair, experiences her first dance.

My sister uses a chair, so the sight of this made my heart swell for every kid in one, or disabled in other ways, who felt seen in and inspired by Nessarose’s joy. Bringing my sister up is perilous, of course, because it suggests my empathy in this regard is limited to my intimate familiarity with such disability. We, as a species, tend to extend our concern to those we care about and not much beyond that. This is what makes Wicked, both the musical and the film, so special — it suggests we can become less selfish. More on that later, too.

Shit, sorry, I got sidetracked again. I still haven’t told you about the moment that made me a Wicked: Part I stan and, as I hyperbolically described, recall the faith I used to have in human beings. No turning back now, don’t worry. Here goes nothing, deep breath, [starts frantically typing]…

The much-alluded-to moment comes late in the Ozdust Ballroom sequence that Nessarose’s dance kicks off. We’re about halfway through the film at this point, and Elphaba arrives, looking silly in a pointed black cap. She quickly realizes she was invited here so her loathsome roommate Galinda (Ariana Grande-Butera) can humiliate her.

Glinda — as Galinda renames herself later — is everything Elphaba is not. She’s blonde, bubbly, popular, and very, very not-green. Did I mention Elphaba is green? Well, she is. Very, very green. It seems to be related to her also having a whole lot of magic flowing through her veins.

It should be noted that all humans in Oz are equal regardless of race and/or ethnicity…as long as you’re a normal human skin color. It means that actors can play these rolls from a race-blind perspective – and Wicked Part I is an explosion of representation (not just race, but body type and identity). But their diverse appearances can – and intentionally do in the film – evoke real-world frustration with women and people of color who collaborate with their own oppressors just to be closer to power themselves.

Glinda and her super-hot boyfriend Prince Fiyero (Jonathan Bailey) are examples of this. While their whiteness and privilege seem irrelevant to other students compared to their social cache – the way everyone centers them at their university – their whiteness and privilege does mean something to audiences like you and me. If Elphaba’s green skin others her, making her a surrogate for marginalized minorities of any kind, then Glinda and Fiyero are there to serve as her foil – but especially Glinda.

The casting of Michelle Yeoh as Madame Morrible, the Dean of Shiz University, is another example of this. On one hand, director Jon M. Chu might’ve just wanted to work with Yeoh again after she starred in his film Crazy Rich Asians (2018). On the other, Yeoh - not Morrible - is a person of color whose character is working to disadvantage others in Oz in order to secure more power for herself. As audience members, it is impossible to distinguish the actor’s real-world race from her Morrible’s actions, which is, I have to say, a stroke of meta genius to intensify many of the Wicked adaptation’s themes.

As Elphaba enters the Ozdust Ballroom — remember, we’re supposed to be discussing the moment everything changed for me watching this film — she realizes the whole student body is snickering at her. She almost breaks, too…but she begins to dance by herself instead.

Fiyero observes to Glinda that Elphaba really doesn’t care what others think of her…but Glinda, who is as narcissistic as her roommate is selfless, knows better.

As we watch the pretty blonde white girl’s face, something happens. She wakes up to another human being’s pain and suffering.

Otherwise known as empathy.

Not for someone close to her, but for someone she hates — or thought she did.

Glinda goes to Elphaba and gracefully saves her from embarrassment. In doing so, she begins a friendship that will carry us through to the end of the film until…well, friendship has its limits when privilege is at risk, as you’ll see.

Christ, there’s a lot of foreshadowing going on here. Do you think it will lead anywhere? God, I hope so.

So, the thing is, I adore the musical Wicked. I’ve seen it performed five times. I know its songs by heart and now even my children can sing along with them.

But its racial element is far more important to the story than maybe the stage was capable of adequately conveying. It’s there, don’t get me wrong, but it’s infinitely more impactful when Elphaba’s green skin is presented in close-up and the face behind all that make-up is a Black woman’s.

I’ve seen a Black woman perform Elphaba before, to be clear, but again, it’s the proximity to my eyeballs that makes the difference here. Cynthia Erivo is…otherworldly in this part. I don’t know how else to describe how radiant, how intelligent, how utterly brilliant she is. This is a star-making turn for the ages, and I’m ready to follow her into Hell itself if it means I can watch her act some more. When she, as Elphaba, starts talking about equality – in this case, the increasingly marginalized talking animal population of Oz – there is a weight to it that cannot be denied because her face is right there in my face.

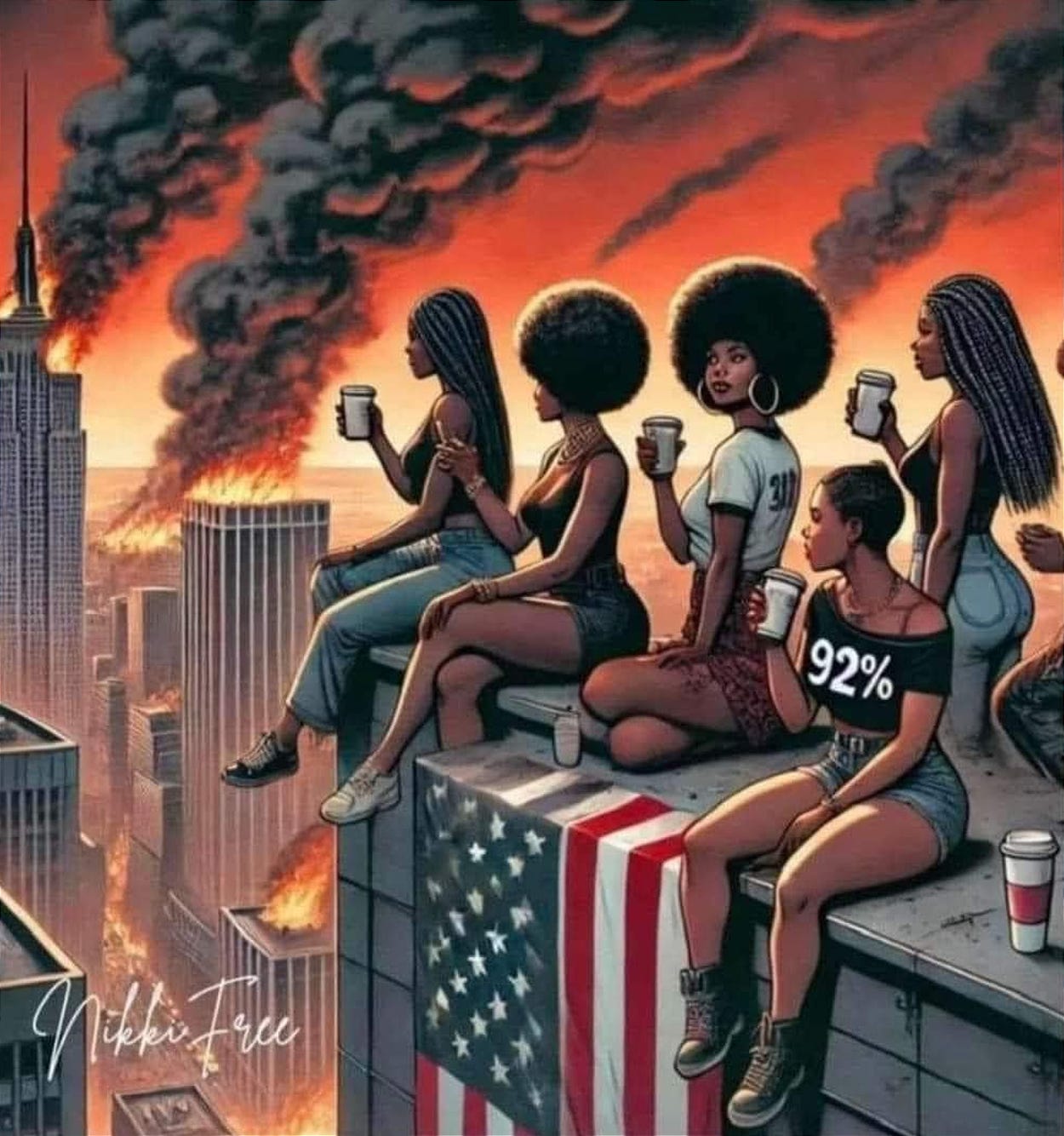

Especially a month after 92% of Black women voted for Kamala Harris and not the white supremacist.1

It’s a common refrain that Black women are the moral core of the United States, as their support for equality and general progress never waivers. They don’t require any special prodding to do their part for themselves and other marginalized, at-risk groups. They show up, over and over, despite being let down over and over by the politicians they help to elect.

This is considerably different than white women. Over the last seventy-two years, a plurality of white women has only voted for the Democratic presidential candidate twice – in 1964 and 1996.2

Twice.

In this year’s election, they supported Trump over Harris, just as they did in 2016 and 2020. If that’s not bad enough, younger white women even slid more Trump’s way, a detail I don’t hear people bring up nearly enough; he got 40% of them, up from 33% in 2020.

I’m bringing all this up because, yes, Wicked is broadly political, but it’s also very much about the U.S. – baked into its DNA since L. Frank Baum created the world of Oz.

When you buy a ticket to see the film – or, if you insist on waiting to watch it at home despite my pleas for you to head to the movie theater right now – you are doing so at an inflection point in history that has seen the majority of white Americans overwhelmingly reject the idea of equality and general social progress in favor of a baseless, but populist message of economic salvation.

Consequently, it is impossible not to now see similar elements in the film and not find their meaning exponentially magnified.

Wicked is, at the plot level, about a witch of unique color discovering that her country’s glorious, god-like leader is a charlatan who secured with lies and continues to retain his power by scapegoating talking animals…some of whom are also actual goats. So, the scapegoating is an unintentional pun, sorry. Anyway, the talking animals are Latino immigrants, Muslim immigrants, other non-white immigrants – basically, the dreaded other people are so quick to xenophobically blame for everything in the real world.

The Wizard (Jeff Goldblum in all his charming, slithering glory) even makes the point to Elphaba that he will say anything to make people like/support him, including bald-faced lying to her that he’s concerned about what’s happening to animals in Oz. Lies are his stock in trade, and eventually he turns them on her, too.

When Wicked hit the stage back in 2005, the Wizard was George W. Bush, who had condemned the United States to years of foreign wars based on a lie – wars that had killed hundreds of thousands by that point. He wanted flying monkeys as spies because Bush had convinced the world Muslim terrorists were hiding everywhere just like those pesky talking animals.

Twenty years later, the Wizard’s elaborate, often nonsensical fabrications to gain and keep “office” makes him seem amateurish next to Trump’s non-existent relationship with the truth. The Wizard’s flying monkeys are even more terrifying in a culture where the most powerful leader in the world is determined to use the power of the state to hunt down and lock up his enemies.

To state the obvious: Elphaba should’ve seen this coming.

Literally everyone around her in Wicked is drowning in privilege, even the Munchkins in their rustic, but beautiful homes. They live spoiled, perfect lives, free from anything like real concern – even for the talking animals they allegedly care about. But to humans, these animals are just servants, useful for things like taking care of wealthy humans’ children and playing funky music at the Ozdust Ballroom.

These are two narratively minor, but thematically major changes made to the Wicked musical for the big screen. I might even call them ingenious strokes of meta genius.

In the first instance, Elphaba and her sister Nessarose are now raised by a nanny who happens to be a bear named Dulcibear (Sharon D. Clarke, notably a Black actress). Their father assigns the most important task in his life to a servant who has no on-screen character other than to essentially say “yessir.” Dulcibear isn’t the only animal employed by the sisters’ affluent family; there are plenty of other animals to be bossed around, too.

With regard to the music being performed at the Ozdust Ballroom dance, consider this first. Throughout film history, Black musicians have been used to add a bit of hipness to scenes even though Black people were rarely allowed to be actual characters on screen. This overlaps with the longstanding habit of white culture enjoying Black music, but refusing to grant Black people equal rights until it was absolutely necessary to keep the country from shutting down. Even today, white people embrace rap and hip-hop, music genres originated within Black culture, while regularly voting against Black people’s interests. It is a perpetually unequal social relationship.

Director Jon M. Chu translates that exploiter/exploited dynamic to the screen by making animals the Ozdust Ballroom’s house band. The animals aren’t otherwise welcome at the dance – just as they soon won’t be in the classroom either.

Dr. Dillamond (Peter Dinklage) is the aforementioned talking goat. He’s also a professor of history, a subject nobody at the university really cares about because history challenges the current narrative the Wizard has manufactured. When a bleating Dillamond is violently dragged away by guards, Elphaba turns to her classmates, wondering how they can sit there and do nothing. Even her love interest, Fiyero – still Glinda’s boyfriend at this point – shrugs impotently. But sit there is all any of the intend to do, watching silently as Dillamond’s human replacement the advantages of a cage. The little lion cub inside it won’t even grow up to speak, the class is told.

Animals forbidden to read or speak…

…locked in cages…

…enslaved.

Elphaba can’t take it, and in her fury accidentally casts a spell that knocks everyone in the classroom unconscious except Fiyero. Before she understands what she’s done, he leaps up, grabs the cub, and they run off together. As they flee, Fiyero insists to her he’s actually self-involved and selfish despite this apparently heroic turn, but Elphaba asks why he’s so sad then. That shakes Fiyero because he’s a white dude who has secret feelings – dreaded emotions – he has to otherwise keep bottled up unless nobody else is looking. Like right now. This all makes him lonely and nothing more than a figment of his own imagination. In reality, all he has is privilege, and he can’t do anything socially that could compromise that — like stand up for the less fortunate than he.

Glinda is even worse than Fiyero.

We don’t notice this, of course – just like Elphaba doesn’t – because all we see is the blonde hair, the bubbly, affable personality, the popularity she’s wrapped herself in to such a degree nothing genuinely human gets out until that scene at the dance I previously described. The “fun” songs Glinda sings, especially her duets with Elphaba, help to obfuscate her self-centeredness, her indifference, her cruelty.

I mean, this is a young woman who ultimately changes here name from Galinda to Glinda “out of solidarity” with her disappeared goat professor. Why do this? Just to make herself look good. It’s all performative, nothing but lip service to convictions that mean nothing to her because her only real desire is to be the center of the universe.

Of course, Wicked - both the musical and the film - tells us she’s one of our two heroines, but that’s a sleight-of-hand trick that exploits our cultural programming that has long established cute blonde women as an ideal, perfect, good. She becomes Glinda the Good, after all, as both stage and screen’s prologues reminds us…but does she? We’ll have to find out in Part II.

Because by the time Elphaba and Glinda finally meet the Wizard, the old Glinda finally reasserts herself. It doesn’t matter how she feels about her “colored” friend – a friend she adopted on her own terms, not out of respect for who she really is – her own interests must be protected.

And it’s in her final decision at the close of Wicked: Part I that the film becomes an unexpected, but oh-so-necessary allegory for what just happened to America.

Wicked: Part I ends, as the first act of Wicked the musical does, with Elphaba discovering that the Wizard is a fascist – specifically, a fascist who had intended to turn her into his own hand-puppet – and rejecting him and the system of oppression he has engineered.

This rejection takes a pretty dramatic form, since it also involves Elphaba achieving her true power and, in doing so, become the famous “Wicked Witch of the West”. She enchants a broom into a flying vehicle, decades before Harry Potter made this mode of transportation sexy, and crashes through a tower window – all while singing about defying gravity. In the musical, this scene is incredibly powerful. The song “Defying Gravity” is rightfully considered a classic now. But on screen, it becomes something indescribably bigger.

That’s probably because Elphaba’s transformation is writ large across Cynthia Erivo’s verdurous visage.

But Elphaba’s escape is also a divorce, in a manner. Because her best friend, her alleged white female ally against all comers, sides…against her. Glinda, only interested in the power structure the Wizard has created – which places her almost at the top of the food chain – demands Elphaba do what the Wizard says, enlist and get all the power he promises her too, stop making everything so difficult all the time. “I hope you’re happy!” she sings bitterly.

Not that Glinda isn’t torn about doing this. “I hope you’re happy now,” she repeats, more as lament of what has to happen next. Of course Elphaba isn’t happy; neither is Glinda. But Glinda is in the Wizard’s inner circle now. There was no way this white girl was going to sacrifice everything she’d worked for, her own dreams of power, for her “colored” friend.

What an impossibly perfect metaphor for real-world white women repeatedly selling out women of color just for a few more scraps from the the true powerbrokers. It’s the story of Western feminism, but especially, I think, American feminism.

Wicked is a stage musical beloved around the world, there’s no denying that. It’s meant so much to so many – including me. But sometimes history conspires to make something great into something unforgettable. Would The Beatles have become The Beatles had they come to America a year earlier or a year later? But they came when they did, when a youth culture needed them most, and they became something bigger than they probably ever set out to be as a result. I think it’s quite possible many of us will feel that way about Wicked’s adaptation in the years to come.

Because a perfect storm of directorial decisions (including casting a Black woman as Elphaba), the intimacy of the big screen compared to the stage, and the re-election of a populist fascist have made Wicked: Part I the ideal film for the tumultuous times we find ourselves in. The bad and the beautiful, the good and the ugly. It’s the cathartic release so many of us need right now.

I’m going to close by saying this is the kind of film Hollywood used to make all the time. The world needs more reaching for similar greatness even if most will fail. That’s because when they do stick the landing — and Wicked does, like a green Simone Biles on her best day — we’re all changed for the better.

Okay, that was…not remotely good. Sentimental, cheesy, just embarrassingly Bad with a capital B. I was trying to tie the ending into the opening paragraph and, well, I overreached. Let’s instead close by simply saying that when Hollywood films do land like Wicked: Part I does, we’re all better for it.

[Whispered quickly before running away]: And changed for the better!

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

https://apnews.com/article/trump-black-women-democrats-harris-base-votecast-0c646e888c999b03d1798e1aa1331937

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/nov/06/election-trump-harris-women-voters

Wow! Thank you for your “non”-review! I haven’t had a chance to see the movie yet, and it being “concert” season, it will have to wait a week or two. I read the book about 20 years ago and saw the play 7 years ago (thankfully not quite as upsetting as the book - songs help). I look at the rest of the “first” world and realize how far behind the US is in so many ways. I’m a white woman who knows many white women and we all voted for Harris. I just don’t get it….

I saved this to read until after I saw Wicked this week. Your essay really summed up how I felt. I am ready to go see it again!