When the Baseball Film Helped Make America (Kind of) Great

Between 1984 and 1994, the baseball genre became one of the biggest draws at the U.S. box office before suddenly going all but extinct. What happened?

When I was a kid, my mother worked at Tiger Stadium in Detroit, Michigan. If you don’t know who the Tigers are, they’re a Major League Baseball team and, in my biased opinion, one of the best ones. I grew up going to games with my father. Playing ball with him in the backyard and with our extended family of German, Polish, and Mexican immigrant descendants are some of the happiest memories of my childhood. My love affair with the sport continued into adulthood, but it was never quite the same. Life’s responsibilities got in the way until I found myself only seeing two or three games a summer. By the time I moved to Los Angeles, where I had to content myself with Dodgers and Angels games, that number dropped to one in most years. Then, my family and I emigrated to the United Kingdom in 2017 and, later, returned to my mother’s native Australia for good. We’ve been abroad for more than seven years now. Since then, baseball has become a more erratic, often elusive joy. I miss very few things about living in the States, but baseball is one of them, which is probably why I inevitably end up rewatching baseball films every year – a quick hit of nostalgia – when a new season kicks off. These films almost always come from a ten-year period in cinema history, too. As the 2024 World Series is set to kick off on October 25th, I thought it might be a good time to discuss this specific decade of big-screen baseball action and mull why its conclusion was, in many ways, the beginning of baseball’s unfortunate decline in American culture, too.

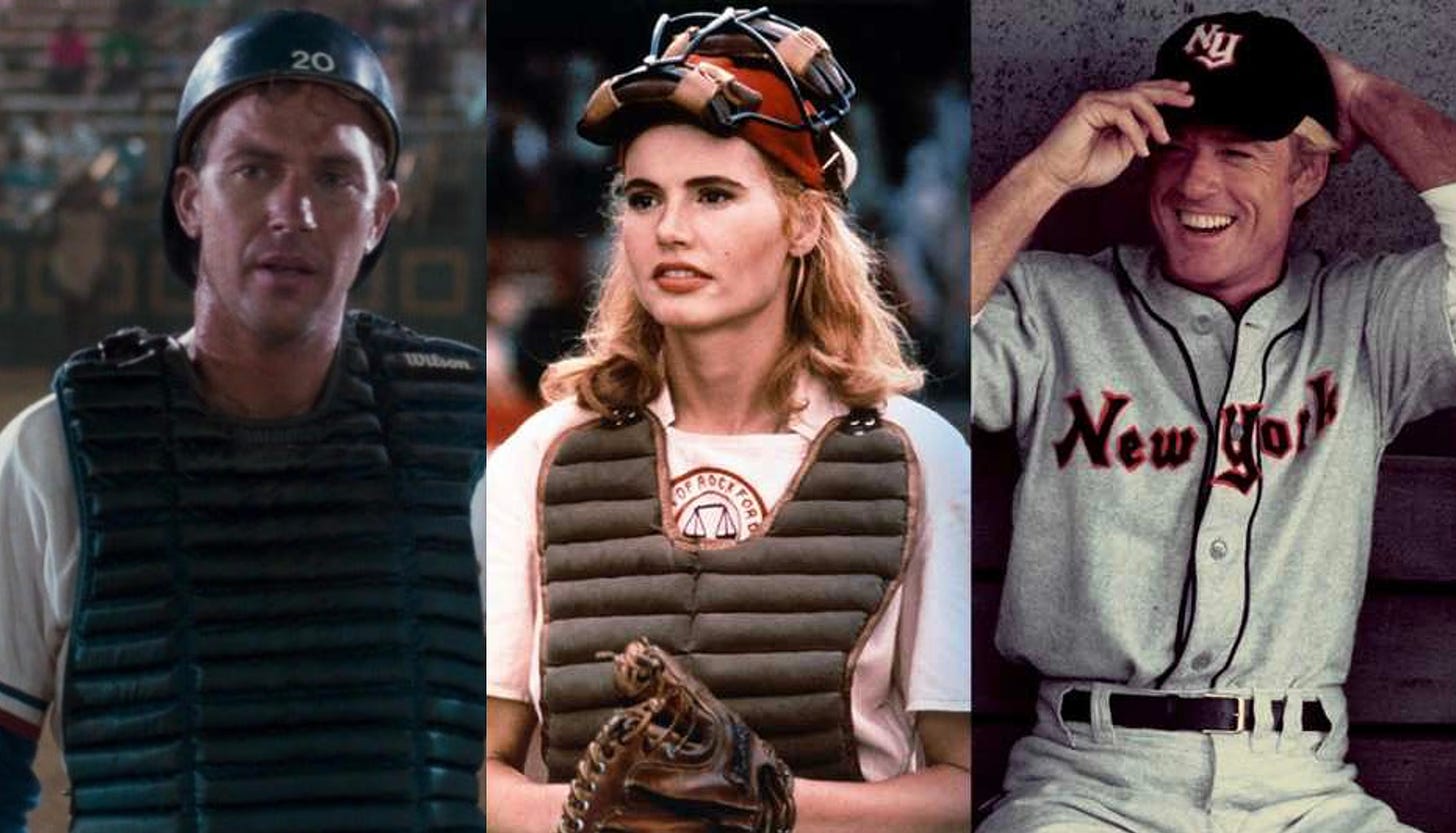

You wouldn’t know it from what gets made these days, but baseball films used to be so ubiquitous that you could’ve called them a genre unto themselves. A genre that reached a high point between 1984 and 1994 and then crashed to such a degree that it’s virtually extinct today. Consider this list of baseball films that were released during these ten years. This isn’t even a complete list, mind you, as I can think of several direct-to-video baseball films with titles I can no longer recall.

The Natural (1984)

The Slugger’s Wife (1985)

Bull Durham (1988)

Eight Men Out (1988)

Field of Dreams (1989)

Major League (1989)

Pastime (1990)

Talent for the Game (1991)

The Babe (1992)

A League of Their Own (1992)

Mr. Baseball (1992)

Rookie of the Year (1993)

The Sandlot (1993)

Angels in the Outfield (1994)

Cobb (1994)

Little Big League (1994)

Major League II (1994)

The Scout (1994)

It’s worth asking what was going on in American culture that might’ve led to this big-screen baseball craze. Nineteen-eighty-four was the year Ronald Reagan was re-elected, winning 49 of the 50 states in the country’s (embarrassingly stupid) Electoral College. Americans had never been and will never again be so collectively drunk on the idea of its own spectacular awesomeness. All the woes of the ’60s and ’70s were officially in the rearview mirror (not really, but go with me), and it was time to bring the country back together around the things that made it great in the first place – unchecked capitalism fueled by patriarchy, systemic white supremacy, and global conquest. Such a feat would require a kind of cultural super-glue to hold it all together…but what form would that take?

Reagan, a former actor, had reintroduced the idea of vigilante justice and manifest destiny to the culture by wrapping himself in Hollywood tropes, from the Western to the war movie. The country had elected this second-rate John Wayne character and given him the world’s largest military to play the world’s sheriff with.

Then, there was the sudden deification of the ultra-rich to consider. “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” also launched in 1984, ultimately running for five seasons; the champagne dreams that came with the ’80s economic boom had every white American male convinced they would one day own a yacht and bang super-models, too. By the way, this is how the world got Donald Trump; he knew what white Americans really wanted was the promise of penthouses, servants of color, and hot blondes on both arms and he sold it to them for decades.

But abstract military conflicts abroad and gold-plated fantasies back home didn’t scream “social bonds”.

That’s what baseball had always provided America, though — a story about what the country was. It brought communities together. It united various immigrant groups in otherwise troubled cities. And since Jackie Robinson crossed the “color line” back in 1947, ending segregation in the Major League, it had become a source of constant and exciting drama between white Americans and Americans of color. There was a theater to it in some ways, watching Black and Latino baseball players destroy white players’ records. Perhaps the culmination of this was Hank Aaron replacing Babe Ruth as the sport’s home run king in 1974. This might sound like conflict – and yes, it was – but we’re talking about a social outlet that every American could participate in.

Well, except for women. But the fairer sex could always watch games — or, preferably, get their husbands beers while the men watched instead. (This is obviously sarcasm, but growing up, a woman who could play ball or called themselves a fan of it was a prize in my community; my grandmother’s prowess at running bases made her “one bad-ass broad”.)

By the time 1984 actually rolled around, the country desperately needed to be reminded of what it once was and, through collective psychic participation in this myth of “America’s favorite pastime”, that was about to happen. None of this was intentional, of course. You can’t manufacture moments like these. But when The Natural was released in May, perhaps the most nostalgic of the run besides Field of Dreams five years later, audiences responded to its hazy gold-hued nostalgia and Hollywood — long a cabal of trend-chasing opportunists — started developing more films like it for them. As these films proved successful, too, the genre began to expand to include comedies and family films. Americans couldn’t get enough of them.

Hell, look at that list of baseball films that were released during this period. Did you see how many of those were released in 1994 alone? Five baseball films in one year. Five! For context, that’s how many superhero films are getting released these days. Oh, and the year even saw the release of an eighteen-hour-plus multi-part documentary about the game from Ken Burns called Baseball. In every way, it felt like a crescendo.

Then, as if with the snap of a finger, everything went back to normal.

It would be easy to pin the blame on Ed (1996) for maiming the baseball film genre – Matt LeBlanc stars with a chimpanzee in what some might argue is the worst baseball film ever made – but genres always descend into parodies and quality collapse after following stretches of such seemingly non-stop growth. I reference superhero films again, to emphasize this point.

No, the more likely culprit was the massive cultural shift that took place in the early ’90s and even around the world. In 1991, Nirvana’s Nevermind really kicked off “the ’90s” as we talk about them today and, by 1994, the film Reality Bites had confirmed America’s youth culture had moved on from the flamboyant neon-soaked excess and general bullshit fantasy Reagan had sold the country. Gen-Xers were now in outright rebellion against everything their parents held dear – which, I would suggest, included baseball.

At the same time, the Major League Baseball season was canceled in 1994 due to a players’ strike. Smarter people than me can explain how the game itself was changing, too, but audiences began to tune out. For example, viewership for a World Series game today is roughly half what it was in ’94 despite the fact that America’s population has grown by more than 33% in the same period.

This seems counterintuitive given how players were being increasingly and exuberantly compensated for their labor, suggesting the sport was, in fact, more popular than ever. In 1984, the average player salary was $329,000. By 1994, that number had more than tripled to $1.168 million. In 2024, the average is now $4.9 million. Perhaps this salary explosion was part of the problem, though. The sport had lost its purity in popular culture. Other sports were paying players similarly, but those sports weren’t the “national pastime”. Baseball had suddenly become part of the capitalist machinery. It was now another get-rich scheme. Another way to sell out.

In other words, by 1994, it had become everything the ’90s ethos was not – meaning it was something to reject along with everything else that had come to define America during Reagan’s two terms as president.

In the three decades since 1994, baseball has largely been absent from big screens except for the occasional title that pops up with what increasingly feels like anachronistic flare. During the early 2000s, there was a brief resurgence of interest, but it faded just as quickly. And then, in 2011, what is probably the last great baseball film that will ever be produced hit theaters – Moneyball, an adaptation of Michael Lewis’s non-fiction book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game. Directed by Bennet Miller and written by Steve Zaillian and Aaron Sorkin from a story by Stan Chervin, it was a direct response to both the hazy gold-hued nostalgia and mythology of earlier baseball films (specifically, from the ten years we’ve been discussing) and how the game had changed in the public consciousness since the mid-’90s.

What I mean by this is that Moneyball is achingly aware of America’s romantic relationship with baseball, to such a degree that characters speak about the sport with a kind of mystical awe that its protagonists regularly disrespect. It’s not something that can be reduced to statistics or truly studied, these sages say; it’s only something that can be felt in their minds. Another way to put this is that baseball is an emotional experience for them — whereas Oakland A’s general manager Billy Beane, played by Brad Pitt in the film, knows better. Oh, once upon a time, when he was a player himself, he believed like they did. He felt it, too, at least until his abilities failed to match whatever “magic” the scouts thought they saw in him. But those days are long gone, and in his improbable pursuit of a World Series championship, he turns to an accountant to help him crack the code. By reducing baseball to a spreadsheet, by abandoning feeling and embracing scientific cynicism instead, they change the game forever.

This all happened, by the way.

But what makes Moneyball a truly transcendent film is how Billy spends most of its running time resenting and trying to blow up outdated, poetic hooey-flooey about baseball and how it works…only to find his way back to his original love for it by the time credits begin to roll. You can read this revelatory scene here, in which number cruncher Peter Brand (Jonah Hill) consoles Billy after the A’s devastating final loss of the season:

No matter how much baseball has changed – and it has changed a lot – it is America’s oldest cultural love affair. There is nothing quite like a night at the ballpark with your father…or with your kid…or with a group of friends. You can sense history everywhere around you, even in the newer stadiums that replaced aging, but still beautiful temples to the sport. And for ten years, between 1984 and 1994, some of the greatest films ever made about this experience – about what it both literally and metaphysically means – were released.

In many ways, Moneyball is the epilogue to this chapter in both cinema and American history. Yet, it also points the way back to something true, something almost spiritual in a spiritually bankrupt world, something many of us have forgotten over the past few decades. Somewhere in that hazy golden hue, somewhere in those poetical myths about the perfect swing, is a dream of what summers mean, what community means, what America means. But unlike the fantasies of America sold elsewhere, this dream was for everyone.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Magic article. Dodgers fan here from the UK and a baseball fan since the first broadcasts live in the early(ish) 1990's. Major League 1/2, Eight Men Out (a particular favourite) and Moneyball for me, but then we have to discuss Field of Dreams, a father and son tale that isn't really about baseball and a movie I LOVE but can't watch anymore as I'm in pieces at the first mention or even hint at a much missed Dad. I've written at length on this within an article here (My Dad in a Field of Dreams) and so I'll only add the obvious: "Hey Dad, you wanna have a catch?" just destroys me. A limey with no connection to baseball. Just a familial connection to my dear old Dad. Love the MLB Field of Dreams games. Even I can turn off my cynicism to enjoy the schmaltz! Great article I'll re-read during the innings breaks in the upcoming Dodgers game! Good luck to you.

Field of Dreams has been one of my very favourite films ever since I first saw it at 15. I know nothing about baseball but I think this film taps into an almost universal nostalgia for a simpler time. It never fails to make me cry but also functions as a comfort blanket.

I haven’t seen many of the later films on this list but I remember feeling in 88/ 89 that baseball films were everywhere. I enjoyed 8 Men Out too, particularly because of its obvious links to Field Of Dreams.

I’ve never seen Moneyball. Going to change that.