Everything You Think You Know About 'Edward Scissorhands' Is Wrong

Careful comparison of the screenplay and film reveals how Tim Burton's fairy tale about a tortured young artist evolved into an allegory for America's dark, hateful heart

Hey, kid, come closer. I have a secret to tell you. I warn you now, it’s going to sound beaver-shit crazy. It’s going to blow up everything you think about a film you quite possibly love. But I’m ready to back up my theory, and if I’m right — hell, even if I’m wrong — it might teach you a thing or two about reconsidering films you already thought you knew everything about. Here goes:

Edward Scissorhands is about the commodification of Blackness by white suburban culture.

Yes, seriously.

RACE IN TIM BURTON’S FILMS

With few details that suggest otherwise, Caroline Thompson’s screenplay for Edward Scissorhands makes no mention of race. But the world it implies — a cookie-cutter pastel suburbia where men go off to nine-to-five jobs, women gossip for sport, and no one wants for anything — is very much white.

America was spoon-fed these tropes every night for decades on shows like “Leave It to Beaver”, “The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet”, “The Brady Bunch”, and many more. Together, they formed a mythology of the country’s alleged Golden Age of middle-class prosperity that persists today. The world that director Tim Burton brings to life in his film looks and operates no different except it makes no pretense of being based in reality. It is a fantasy world, outside of time, populated almost entirely by cruel, selfish, and xenophobic white people who hide these qualities behind big smiles, a veneer of community, and virtue signaling.

As for the titular Edward (Johnny Depp), he’s a scissor-handed art-kid from the nearby gothic castle whose arrival breathes exciting new life into the otherwise monotonous suburb. He’s an outsider. A freak. His black costume and deathly skin color suggest he’s goth, his hair maybe emo. When you consider the filmmaker who dreamed him up — Burton — is a person who looked pretty much just like Edward at the time Edward Scissorhands was made (sans bladed digits), there seems to be no doubt that the character is some kind of avatar for him and his self-perceived creative otherness. The film, thus, might be seen as a portrait of a tortured artist as a young man, trying to be original and beautiful in an ugly world. In fact, this is how I looked at it for decades.

But in more recent years, I’ve begun to see it as much more than that. Before I break down why, I want to acknowledge that Burton’s oeuvre is pretty much as white as you get. I haven’t actually tried, but I’m willing to bet good money that you can count significant Black characters in his films on one hand. In 2016, the director was given a chance to answer a question about this from journalist Rachel Simon. His response:

"Nowadays, people are talking about [diversity] more … but things either call for things, or they don’t. I remember back when I was a child watching The Brady Bunch and they started to get all politically correct. Like, OK, let’s have an Asian child and a black. I used to get more offended by that than just… I grew up watching blaxploitation movies, right? And I said, that’s great. I didn’t go like, OK, there should be more white people in these movies."

Obviously, this response is extremely disappointing, to say the least. It also argues pretty loudly against any possibility that Burton smuggled a race allegory into his beloved goth fairy tale. But I think there’s more to it than that, and I want to suggest that a single decision in the casting of this film and the changes to the script it resulted in during production transformed the director’s deeply personal story into a much more powerful race allegory. This phenomenon — of a film acquiring new, likely unintentional meaning because of a creative decision during its genesis — is something I’ve written about recently, by the way, in “A Tale of Two (Unlikely) Heroes: 'Night of the Living Dead' and 'Alien'”.

OFFICER ALLEN

Edward Scissorhands’ cast is as lily-white as you’d expect from my description of the film so far – with one exception. Yes, one. That exception is Dick Anthony Williams, a Chicago actor whose work primarily fell into the B-film category, but who always elevated whatever he came into contact with. Edward Scissorhands is no different.

A cinematic aside, for those who find these things fascinating: Williams was an actor of some note in blaxploitation films, which you just saw Tim Burton refer to in the quote I shared. Former blaxploitation stars — including Billy Dee Williams, Pam Grier, and Jim Brown — tend to populate his twentieth-century films the same way Hammer film actors have.

As for Williams’ role in Edward Scissorhands, he plays Officer Allen in it – the only respectable cop with speaking lines in an all-white town…who also happens to be, you know, a Black man. He makes his first appearance when Edward breaks into a local house at the direction of Jim (Anthony Michael Hall), but really to make the character of Kim (Winona Ryder) — his love interest — happy. When Edward is later released, Allen expresses genuine concern about the man-child’s well-being, even saying he doesn’t want his worrying about the kid to keep him up at night. In short, he’s not just respectable – he’s a good man.

Let’s take a look at how this noble character is introduced on the page:

As you can see, there is no mention of race in the screenplay. Officer Allen receives no description on the page beyond his name. Because of this, it might be reasonable to think that Williams’ part in the film is the result of race-blind casting. Just the best actor for the job, that sort of thing.

But the reality is, Burton’s casting of Black actors always feels consequential because of how rarely it happens. Especially here, where he’s the only one Black character on the screen. It inevitably means more, and now the question is: what does it mean?

More specifically, was it a random act of tokenism by Burton, a small narrative gesture meant to heighten a climactic moment I’ll describe later on, or — as I believe — a small narrative gesture that transmogrified the Edward Scissorhands story into a powerful race allegory?

EDWARD

Now, let’s turn our attention to Edward to understand his part in this alleged race allegory I am presenting to you.

He’s the art kid, the goth, the emo freak with scissors for fingers. In every possible way, he does not fit into this sleepy, monotonous suburban community. Maybe he’s supposed to represent the hippies’ counter-cultural revolution that Tim Burton grew up during, but I’m skeptical. Consider the following:

Edward is a teenager. A boy, really. But how do the suburb’s residents react to him? At first, with a degree of healthy curiosity that wouldn’t have been afforded to hippies. Life is boring and he seems like a refreshing change of pace.

There is one naysayer in this regard. A Bible-thumping housewife who insists Edward is the Devil. Her language dehumanizes the kid. It’s the kind of thing white Christian hegemonic groups have said about every marginalized group from Black people to Jewish people to members of LGBTQIA+ communities for centuries.

Then, Edward creates his first topiary. It’s his first artwork. He’s an artist, we discover. Art is sexy, art is cool. Now, everyone wants a piece of him. They all want to say they have one of his topiaries, as if he’s the Banksy of ornamental hedging plants. So what if he’s a freak, so what if he isn’t one of them, they’re willing to make exceptions for him if they can rub up against whatever makes him so special and maybe get a little of his magic dust on themselves in the process.

Then, Edward styles a woman’s hair. Oh shit, all bets are off now. The ladies, bored and gossipy and sex-deprived, line up to let him put his hands all over them. They’re aroused by it. It’s downright sexual. In other words, they’re now openly sexualizing this other, this outsider, this freak. There’s no hint of respect. They don’t pay him. They use him. They exploit him like a cabana boy. Except cabana boys get paid. Enslaved people don’t.

And then, Joyce (Kathy Baker) decides to play the part of the “white savior” in this artistic dynamic and provide Edward with a way to create his art in a salon. It’s a partnership that will obviously financially benefit her much more than him given how his talent, coolness, and general exoticness will no doubt attract a lot of other white suburban housewives. To celebrate, Joyce attempts to seduce Edward. Edward, frightened by the sexual aggression of this white woman, flees.

It's at this point that Officer Allen enters the story. He brings with him the third act of Edward Scissorhands. But before I get into the finale, reread the description of Edward’s journey so far. Imagine his deathly pallor replaced by Black skin. Imagine his wild hair (atypical for this environment) replaced by (similarly atypical) Black hair. Imagine his scissors vanishing, replaced by a guitar or a singing voice as his gift. Imagine Joyce as the white music producer trying to turn a gifted Black kid or kids into a product to be exoticized and sexualized for the entertainment of white suburbanites who otherwise have no interest in the well-being of such outsiders. In other words, Black people who are allowed to exist for the entertainment of white people, but not as whole individuals and only on the white people’s terms.

Just like Edward.

Have I convinced you yet? If not, read on because I’m only building up steam here.

ACT 3 ON THE SCREEN

Post-robbery attempt, things don’t go especially well for Edward. I want to begin by focusing on three critical beats that show up onscreen, then describe two that don’t.

The Morality Lesson

Throughout supper, the benevolent white family that has taken Edward in blame themselves for his experiment with criminality. They failed to teach him, this outsider, this wild and savage man-child, the ways of decent folks like them.

Translation: white lawgivers, the keepers of civilization — as well-meaning as they are — expect Edward to behave as they instruct him to without ever recognizing how their culture is traumatizing or exploiting him.

As originally conceived, I do believe this scene was meant to play innocently compared to what I’m describing here. If anything, the youth at the dining table — Edward, Kim, and Kim’s brother Kevin — disagree with the parents’ rules. It’s youth culture versus the establishment. It’s fun and funny with a hint of social relevance informed by the age both Tim Burton (b. 1958) and Caroline Thompson (b. 1956) grew up in. Fair enough.

But the presence of Officer Allen warps this generally innocuous original intention. Details begin to rapidly accumulate around his appearance, forcing us to recontextualize how we’ve looked at so many of the creative decisions that show up in the final film.

Accusation #1

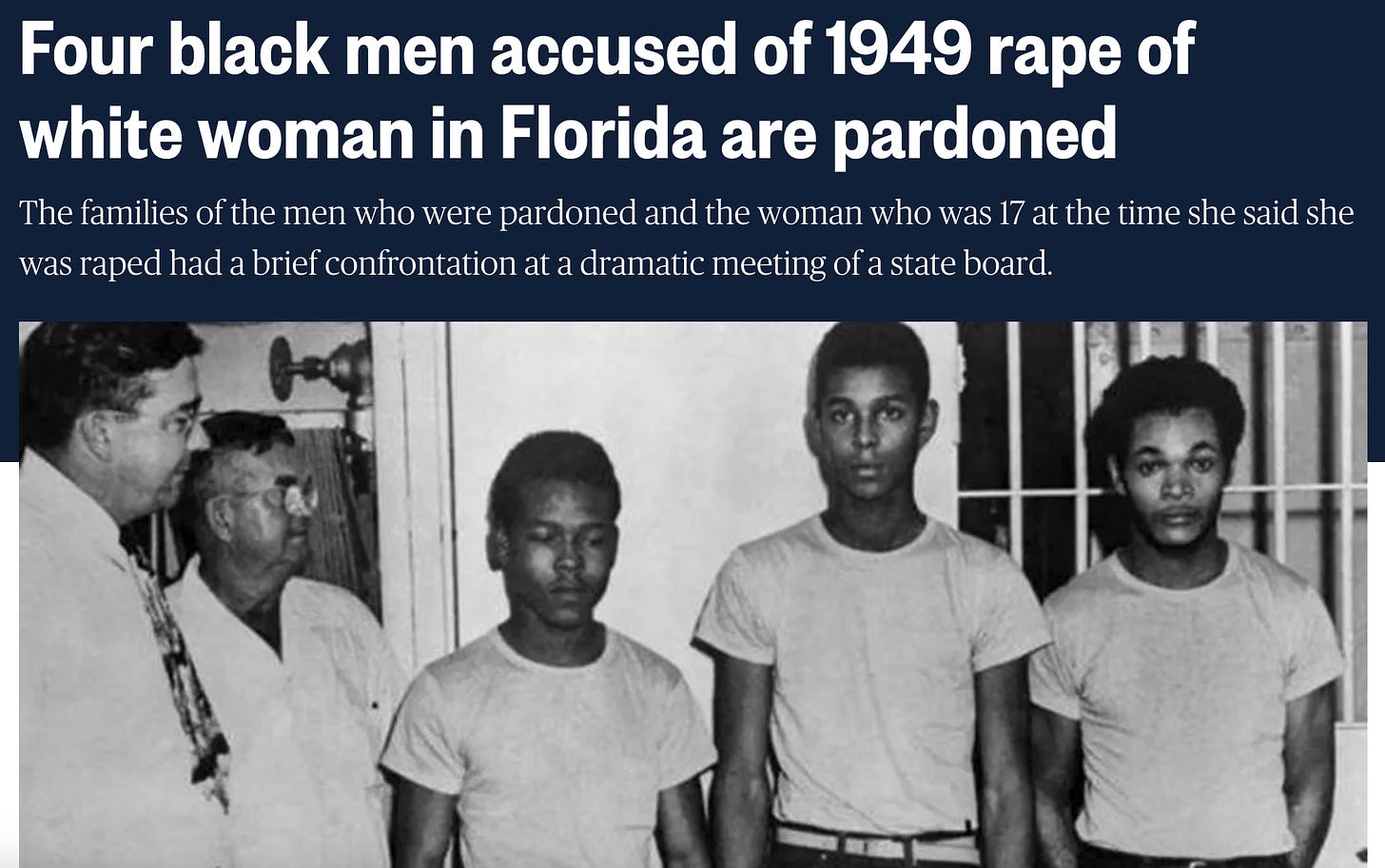

Once her fellow housewives turn on Edward, Joyce begins to tell them about how he tried to rape her. Suddenly, he’s a sexually potent savage – or so she tries to portray him as an act of retribution for not letting her get a piece.

Now, if I have to tell you that Black men have died in horrific and incalculable numbers because of false rape accusations by white women over the past couple of centuries, then you don’t know nearly enough about American history and need to open a book or ten on the subject. This is what led to the stereotype of Black men as insatiable brutes, an image that appears in D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), in countless other films and TV series over the years, and as part of decades of ads and political campaigns. I mean, one of the angles of the campaign to criminalize marijuana was that it made Black men rape white women.

In short: white women pointing a finger and crying “rape” at a Black man has long been a sure-fire way to get a Black man murdered or, if he’s lucky, locked up for years. This is exactly what happens to Edward in Edward Scissorhands, as I’m about to show you.

Accusation #2

This accusation comes from Jim, the jock boyfriend of Kim who is bested by the sexy artist-outsider with scissor-hands. Kim has obviously chosen Edward over him. In the screenplay, the scene is more involved and intense, and Jim reveals that he doesn’t even see Edward as human. It’s typical othering, which can justify any level of violence — such as Jim trying to later murder Edward in his castle.

ACT 3 ON THE PAGE

There are two scenes in Caroline Thompson’s screenplay that don’t show up onscreen as they do on the page. This isn’t remotely unusual, nor should one read anything into it except for original intent before the acts of production and post-production and what they revealed to filmmakers began to change things.

The Magnanimous Parents

In the film, Kim’s parents Peg and Bill, played by Diane Wiest and Alan Arkin, are charming, endearing, loving people. On the page, they begin that way, too, but slowly they’re revealed to be lousy human beings like almost everyone else in their suburb. The trauma the community inflicts on Edward just proves too…well, inconvenient to them.

Perhaps most pathetically, Peg complains about how her Christmas party was ruined by Edward’s troubles. The parents, we realize in the script, had been profiting off of Edward, too - their coin in this realm made more valuable by his presence in their home. This works on the page, I think, but would’ve felt like a cruel betrayal to audiences onscreen when even Peg and Bill turn on Edward like everyone else.

In the script, Kim reacts with disgust to their behavior, which is a damning indictment, I think, of superficial attempts by white America to address the consequences of slavery and the ensuing economic gap Black Americans have had to endure for generations. Here’s one for white saviors everywhere:

The interesting thing is that Peg still manages to reveal her true colors onscreen, albeit in the guise of concern for Edward. But what she’s really saying here is a softer, more palatable version (for audiences) of what she says in the script:

“You know, when I brought Edward down here to live with us, I didn’t really think things through. And I didn’t think about what could happen to him, or to us, or to the neighborhood. And now I think that maybe it might be best if he goes back up there. Because at least there he’s safe, and might just go back to normal.”

Do you see her real concern here? What could happen to her family and the world she belongs to. To her comfort. To her normal life.

Edward can go back to his normal life, sure, how very considerate - living in a derelict castle outside of town.

In other words: integration is a pointless endeavor, according to Peg. The savage she tried to clean up and pretend she could civilize will never belong in her world.

This is all language that was used to oppose the emancipation of enslaved people in America and then throughout the Reconstruction era. It shows up in The Birth of a Nation (where the allegedly ape-like qualities of the beastly Black race is played up for laughs) and, of course, racist language today. “He speaks so well” is a first cousin to everything Peg is saying to Kim in this scene.

Accusation #3

Another major change in the film from what appears in Thompson’s screenplay is the radicalization of Kim’s brother Kevin on his walk home. As the rest of the suburb panics over Edward, some even pulling up seats to watch the events about to unfold as if it’s entertainment, the boy has no choice but to react to their comments. Their hate-drumming begins to infect him until, at the point that he sees Edward, he shouts, “There he is!” Kevin doesn’t see the van barreling toward him, but Edward saves his life. As the boy panics, Edward accidentally cuts him, drawing reactions from everyone around them.

Another way to put this: the accuser — the violator — is harmed and the violence he brought on himself further heats up the crowd’s temper. Kim’s family yet again betrays Edward, leaving only Kim and, as you’ll see, Officer Allen on Edward’s side.

In the film, Kevin doesn’t understand what’s happening in his suburb. He returns home, where Edward bursts from the house to save the boy’s life from the oncoming van. Kevin never sells Edward out. Even Bill, when he pulls Kevin away, does not turn on Edward. Peg tells Edward to “come home”, but we already know she intends to banish him back to — my words, for emphasis — the country he comes from.

HOW IT ALL ENDS

In the film, the crowd is now made up of howling, blood-thirsty maniacs feeding off of each other’s hate. In other words, a mob.

Worth noting, Caroline Thompson’s screenplay refers to this mob as “vigilantes”. Vigilante justice is an American idea, predicated on Wild West tropes but really the idea of controlling the most violent, unwanted elements of society - in other words, Black people, Mexicans, Native Americans, etc. (I’ve written about this deeply, incredibly toxic American trope here, if you’re curious).

At this point, Kim tells Edward to run, and he does, fleeing back to his castle. The mob pursues him. At the head of the group, in his police cruiser, is none other than Officer Allen.

The only Black man in this suburban hell is leading the mob…or is he?

Because Allen gets to the castle first. Here’s how the scene reads in the script where, remember, Allen’s race is not described:

But in the film, Officer Allen doesn’t just drive Edward off. He, a Black man — for whom the lynch mob almost exclusively existed in America — turns and confronts the lynch mob. This imagery is powerful. A Black man with nothing but morality on his side stands up to a mob intent on murdering a falsely accused young outsider (Black man). He lies, and tells them, “It’s all over, there’s nothing more to see” – a detail not found in the script. “It’s all over,” he repeats more firmly, then drives off.

Whatever you think of my arguments here, there is no way of getting around this scene. Tim Burton cast a Black man to play the only truly moral hero of his story, knowing full well that he would be projected onto the big screen standing up to a lynch mob of white suburbanites. That was a decision, one with significant ramifications for how we read this scene and also how we read every single one that preceded it – because Allen empathizes with Edward in a way nobody else in this community does. He sees something familiar in him, he worries about his physical well-being, and he ultimately comes to his rescue.

By casting Dick Anthony Williams as Officer Allen, every scene in Edward Scissorhands takes on meaning not found in the script. By altering that script on set, by having Williams/Allen stand up to the mob, Burton also revealed his awareness of what was happening to his story when he did this.

Regardless of whether Burton and Thompson were originally drawing upon more universal anti-establishment tropes, each of these tropes crystalized onscreen around a central idea. That idea being Edward is every Black artist whose work white suburbanites want to listen to, but whose life white suburbanites don’t actually find valuable - who must live according to white rules, who can be casually accused of the most heinous of crimes as a form of punishment, whose body can be just as casually destroyed for social sport.

In the end, Edward only survives the film, to become a fairy tale monster living in a fairy tale castle, because Kim — not Officer Allen — tells the mob the lie that Edward was killed. It’s a fairy tale ending because, in real life, the cop would’ve killed Edward and, if not, the mob would’ve.

Read Caroline Thompson’s screenplay for Edward Scissorhands here.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

The article and these comments give me a lot to think about. I enjoyed Edward Scissorhands when it came out, though I couldn’t tell you why, though I think it was Kim’s caring about Edward showing the humanity in this Frankenstein like tale. Your explanation works, as well. Of the two films mentioned above. I disliked Wall Street and hated Glengarry Glen Ross. Maybe because I had an inkling of what they would come to represent?

Alternative reading: it is an allegory of film-making, or maybe maleness. Tim Burton, the outsider, sees and observes things that have grown naturally such as hedges or hair, cuts them down (“the cutting room”) into a meta shape (a horse, a hair-do). This ability gives him acclaim and access, proximity to, maybe even intimacy with women, but he is not an ideal lover, with hands that can only cut, reduce. They can shape but cannot create live.