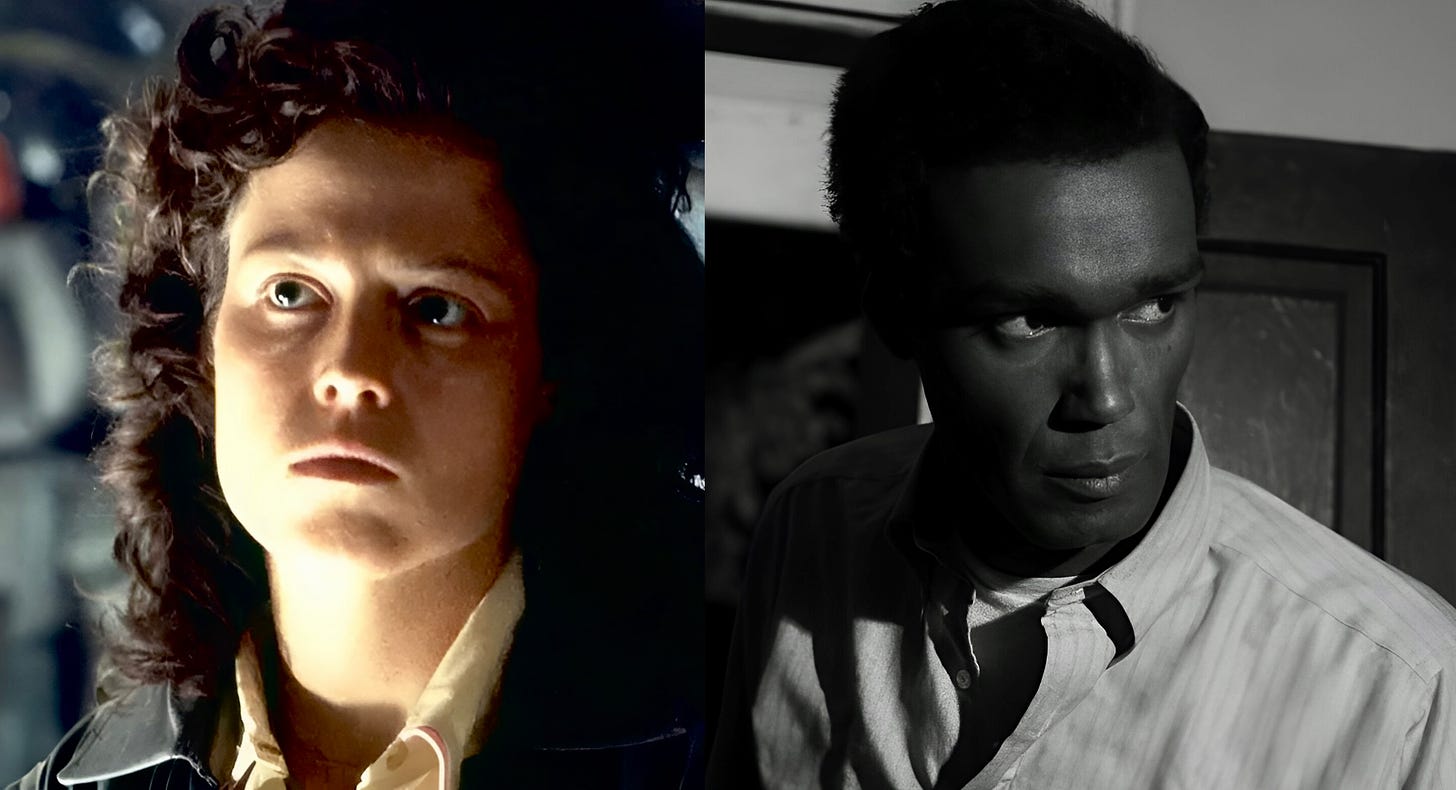

A Tale of Two (Unlikely) Heroes: 'Night of the Living Dead' and 'Alien'

By challenging traditional narratives, two very different films helped to redefine who could be American action heroes. What can they teach us about our own storytelling?

In 1967 and in 1979, two similar creative decisions on two very different films helped to redefine who could be a hero on American movie screens. While the analysis I’m about to offer will certainly reflect the truth that representation matters, my intent here is more to demonstrate how single decisions can transform your work, imbuing it with unexpected and even enduring meaning. Hopefully, it will empower you to interrogate the art you are working on in new ways and wonder how you can also challenge professional and cultural — and even your own — norms. After all, that’s how we got NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD and ALIEN.

NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD

George A. Romero’s horror classic offers up many firsts. For example, it gave birth to the modern interpretation of flesh-eating undead zombies, tossing out the previously traditional cinematic notions of living zombies as victims of mind-controlling voodoo. It also gave rise to the tradition of “splatter films”, exploitation flicks that traded on gore and other kinds of graphic violence. Michael Myer, Jason Voorhees, and Freddy Kruger all owe an existential debt to him. But for me, NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD’s most enduring aspect is Romero’s decision to use zombies in it and his subsequent zombie films as vehicles to discuss social issues.

Romero and I actually discussed this long, long ago over Bloody Marys poolside at the Four Seasons Beverly Hills. Don’t worry, I’m not that cool. I was a freelance arts journalist back then, writing for Village Voice Media, but that doesn’t mean being asked to have a Bloody Mary with one of the O.G. masters of horror wasn’t one of the coolest things to ever happen to me.

Using zombies to explore humanity’s worst qualities was a central tenet of Romero’s “Dead” films and he didn’t understand films and TV that used zombies otherwise. That said, his original intent, based on how he directed the film, was clearly to critique various American institutions such as the news media, the nuclear family, and the U.S. government and its Cold War approach to civil defense.

Notice I don’t mention “race relations” there.

That’s because THE NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD’s script made no mention of race. Neither does the finished film. This is only notable given the fact that the star of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD is a Black man in a period when Black actors almost exclusively played roles subservient to white actors on American screens. Remember, IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT, in which Sidney Poitier plays the unforgettable Detective Virgil Tibbs — “They call me Mr. Tibbs!” — was only released the year before.

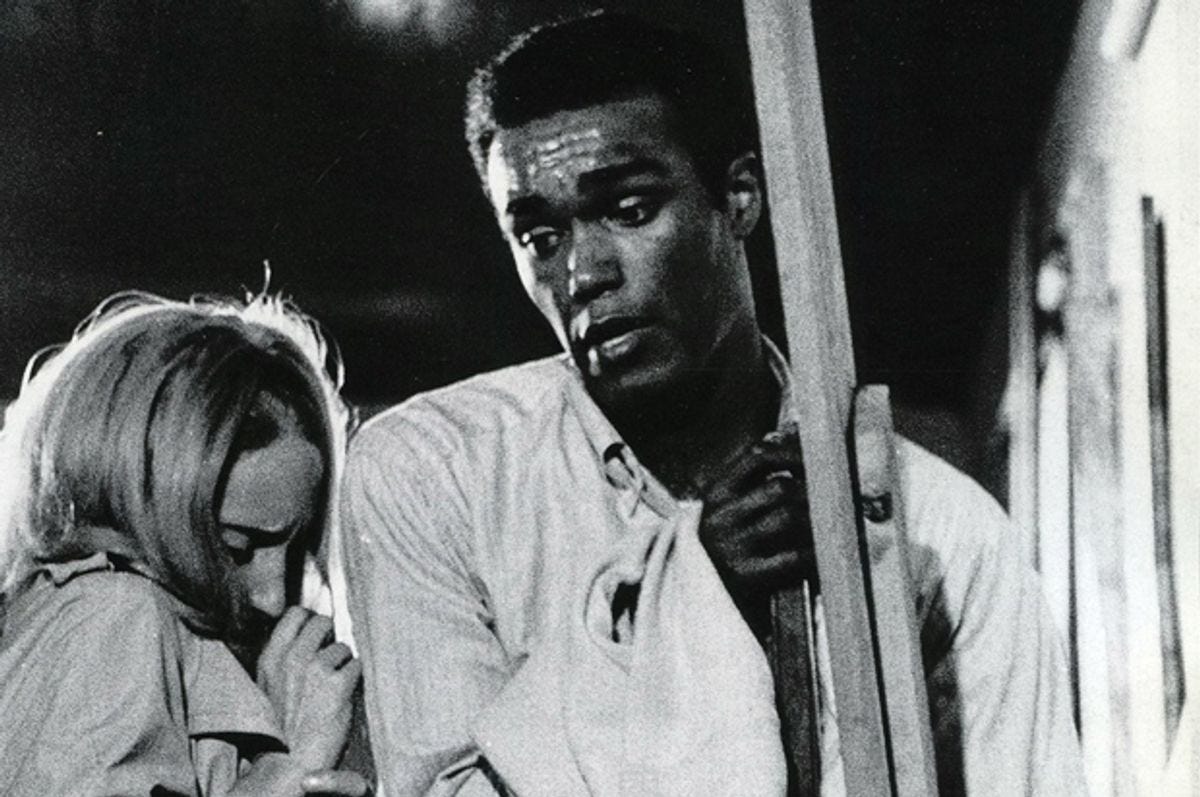

Duane Jones showed up to audition for his part as Ben, a white character called “Truckdriver” at the time, and quickly outshone the competition. In what proved to be a fateful decision Romero concluded he was the best actor for the job and cast him as the calm, level-headed voice of reason in a houseful of white characters losing their damn minds when faced with inexplicable horrors. Interestingly, Jones’s deep voice and distinguished college student vibe is the polar opposite of how Romero originally described the hillbilly Truckdriver.

A man stands in front of her. He is large and crude, in coveralls and tattered work shirt. He looks very strong, and perhaps a little stupid.

This one small change to Romero’s story would imbue NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD with startling new meaning that would come to overshadow all others.

This isn’t to say that the multi-textual themes Romero sought to explore aren’t present onscreen. As I said, they’re all there, his intent evident from the start based on his directorial approach. But the presence of a Black man, one you’re meant to respect, immediately makes the film a race allegory in 1968 and one that speaks louder than all the other issues playing out inside a Pennsylvania farmhouse besieged by flesh-eating ghouls.

In retrospect, the complete absence of conversation about race in NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD is one of the reasons why it’s such an effective piece of art that continues to be celebrated today.

Consider Barbara (Judith O’Dea), the kind of white woman who might’ve gotten a Black man lynched in the sixties with a casually aimed finger. When she begins to panic over the sight of a skinless human face, Ben makes his first appearance. She reacts in horror, ostensibly because she doesn’t know the intruder here to help her, but we know — we know — she’s really reacting to a Black face.

In another sequence, the snarling xenophobe Harry (Karl Hardman) tries to talk down to Ben, telling him what to do like a white man used to always being listened to no matter how ridiculous he sounds. But Ben meets him head-on without blinking, putting him in his place. It only makes Harry meaner and more dangerous, being belittled in this way by, of all people, a Black man.

Then, there’s the smack. Barbara, hysterical, starts to scream. Ben, afraid of how she could endanger their security, lands a palm on her cheek. It’s almost as shocking as Poitier slapping a white judge in IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT the year before, diminished only by Poitier doing it first. For many, it remains a reason to whoop loudly.

By the film’s final sequence, Ben, the farmhouse’s lone survivor of the zombie massacre, emerges from the basement where he has taken shelter. He approaches the window, covered as it is with boards. He peeks between them, pushing the curtain aside, and – bang! – his head snaps back and he crashes to the linoleum. Dead.

Outside, rednecks, led by a police chief with a drawl and commanding a legion of cops and volunteers with snarling German shepherds, declares, “Good shot!”

Audiences are then hit with a series of grainy B&W photographs of zombie bodies being collected and tossed onto a pyre. Ben’s body is picked up with meat hooks, as if he’s less than human, and heaved onto the pile of burning monster corpses. We watch in horror as our hero goes up in flames.

Interestingly, this sequence was in the original script, but Romero sought to change it to have his Black character triumph. No doubt, to make a statement. Jones told author Joe Kane, for the book NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD: BEHIND THE SCENES OF THE MOST TERRIFYING ZOMBIE MOVIE EVER MADE, he was personally responsible for making sure this didn’t happen. “I convinced George that the Black community would rather see me dead than saved, after all that had gone on, in a corny and symbolically confusing way,” he said. “The heroes never die in American movies. The jolt of that and the double jolt of the hero figure being Black seemed like a double-barreled whammy.”

Yes, yes it was.

Red necks. “Southern” cops. German shepherds. The body of a Black man, of someone who got “uppity” for the runtime of the film, is desecrated and burned for his sins of thinking he could be a hero.

What are we to make of this?

Romero had a script for NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD when he set out to make it. He intended for a white man to be out front. He cast a Black man instead and then, with Jones’s help, improv’d like a jazz musician onset to bring some of these elements more to the foreground. But it’s possible to watch this film and imagine it with a strong white male lead instead of Jones. The traditional hero. Every moment of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD would still work this way and the end result would allow those other thematic elements I described, like the criticism of America’s Cold War defense strategy, to really command our attention instead. But with Jones’s face up there on the screen, the film can’t help but become something else – meaning that was heightened all the more by the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. earlier in 1968. The consequence is NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD became one of the most important films made about race during the American Civil Rights Movement…all because of a single, surprising change to the intention of the original story.

ALIEN

“In space, no one can hear you scream.” It’s an iconic tagline, to go with an iconic film, but, for my money, ALIEN only ended up that way because of a casting decision as culturally outlandish as the one that helped make NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD immortal.

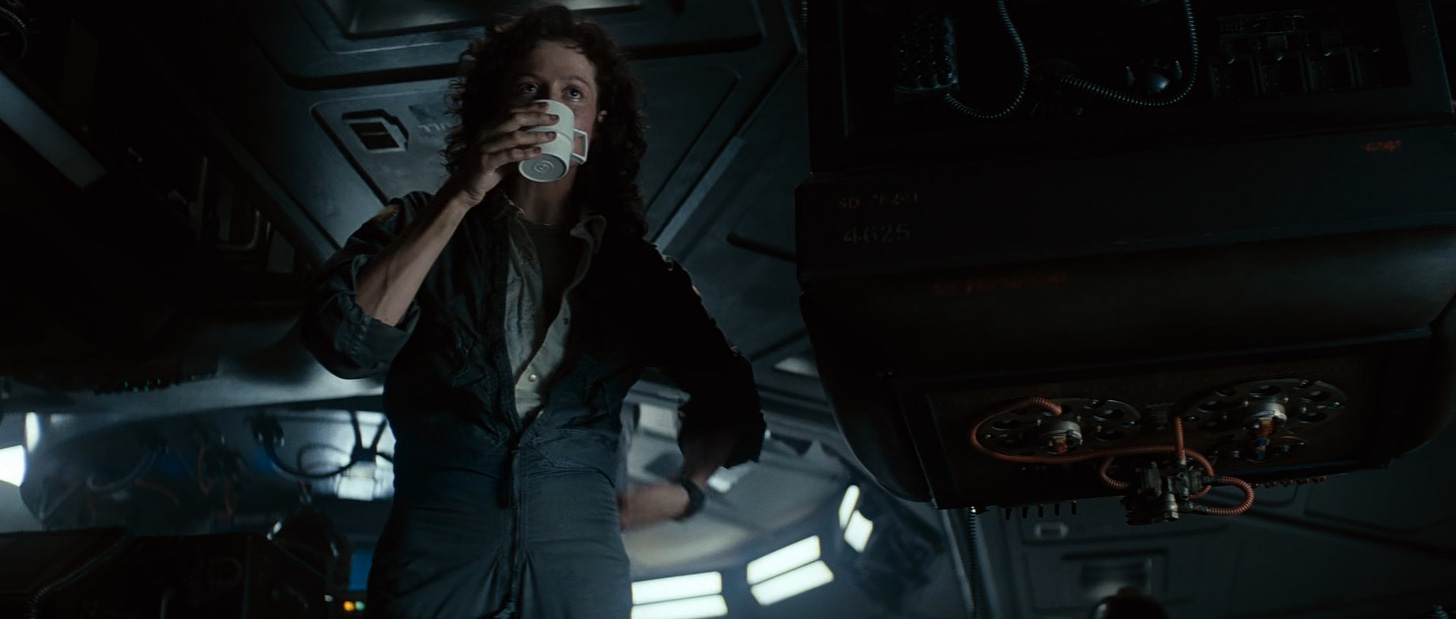

Before I go on, it’s necessary to understand the film’s pedigree for any of this to make sense. It hit screens in 1979, and was directed by Ridley Scott from a script by Dan O’Bannon and a story by O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett. Famously, though, O’Bannon and Shusett’s work (which as near as I can tell culminated in 1976) was rewritten by Walter Hill and David Giler. Hill and Giler’s final draft was delivered in June of 1978 and is a masterpiece on the page that all screenwriters should study in detail if they haven’t already. These two “final drafts” of the same film predictably bear many similarities. Characters, however, are not one of them – including the now-iconic hero Ripley, often called cinema’s first action-heroine, who only first appeared in the script from Hill and Giler (who don’t receive credit as writers on the final film, but do get producer credits).

For my money, the only female character who rivals Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) for the title of “greatest female action hero of all time” is Sarah Connor. I give Ripley the edge because she pretty much takes no bullshit from the get-go, but not in the way male action characters would do this. She’s not physically tough, though she is willing to fight. She’s not a weapons master, she doesn’t know kung fu, she isn’t even necessarily the smartest person in any room she’s in. She’s just the calm, level-headed voice of reason in a spaceship full of characters losing their damn minds when faced with inexplicable horrors - not dissimilar to Ben’s presence in a farmhouse full of hysterical white folks.

Let’s look at how O’Bannon and Shusett dreamed up the crew of the…er…Snark. That’s the name of the mining ship in their draft. The Snark, not the Nostromo ALIEN fans are more familiar with today. This is from their script:

CAST OF CHARACTERS

CHAZ STANDARD,

Captain.................A leader and a politician. Believes that any action is better than no action.

MARTIN ROBY,

Executive Officer.......Cautious but intelligent -- a survivor.

DELL BROUSSARD,

Navigator...............Adventurer; brash glory-hound.

SANDY MELKONIS,

Communications..........Tech Intellectual; a romantic.

CLEAVE HUNTER,

Mining Engineer.........High-strung; came along to make his fortune.

JAY FAUST,

Engine Tech.............A worker. Unimaginative.

The crew is unisex and all parts are interchangeable for men or women.

I think this final line of description is very interesting. And, frankly, audacious for the period. A whole cast dreamed up to essentially be gender-neutral, at least on the page, with final decisions to be made at the time of casting. It’s a kernel of an idea that might have even led to what happened in Hill and Giler’s draft.

Now, let’s look at the character list from that other draft from Hill and Giler:

Dallas.........Captain

Kane...........Executive Officer

Ripley.........Warrant Officer

Ash............Science Officer

Lambert........Navigator

Parker.........Engineer

Brett..........Engineering Technician

Jones..........Cat

Five men and two women: Lambert and Ripley.

This means that in Hill and Giler’s draft, genders are clearly defined. Therefore, their draft defines the lead of a seventies-era action-horror film as a woman. A decision that was, I hope I don’t have to tell you, almost as unheard of at the time as casting a Black man as the lead of any kind of film in the sixties.

Now, let’s break down what this single decision does to the screenplay that makes only the vaguest of references to Ripley’s gender and, except for a single sex joke made by Parker (Yaphet Kotto) to Lambert (Veronica Cartwright) and taped-up nudie mag pics, doesn’t seem to be aware of its character’s genders. This doesn’t mean what was ultimately shot, because, yeah, that five-sizes-too-small panty scene complicates everything. More on that in a moment, though.

First, let’s consider Ripley’s voice. Not how it sounds, but how she uses it. From the moment she climbs out of the cryostasis tubes, she’s there to point out all of the stupid decisions the male characters are making. She’s being reasonable. She’s being cautious. She’s — gasp! — following the rules. For example, don’t let the infected man back on the ship without quarantining him first. Had anyone listened to her, nobody aboard the Nostromo — with the exception of the character of Kane (John Hurt) — would’ve died.

Second, it’s worth noting the sexism and misogyny of the android Ash (Ian Holm). Ash, who also first appears in Hill and Giler’s script, regularly dismisses Ripley’s authority, outright disobeys her orders, casually suggests a subject is beyond her understanding, and ultimately tries to murder her by making her deep-throat a rolled-up nudie magazine. No other member of the roughneck crew treats Ripley with a moment’s disrespect — if anything, she’s treated more seriously than others are — but Ash, an android programmed with all kinds of cultural biases, is a total woman-hater. That said, none of this is ever explicitly stated. Like Ripley’s voice as I described it, it’s implicit. More on that in a moment.

Third, Ripley’s survival at the end of the film echoes Ben’s at the conclusion of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. The characters who should’ve never been there to begin with, who could’ve survived just fine on their own, somehow make it through communal nightmares. The difference, of course, is that Ripley makes it to the credits, defeating the xenomorph that made mincemeat of the rest of the Nostromo’s almost entirely male crew. Ben, on the other hand, is essentially murdered for his Blackness and turned into grainy post-mortem photographs — which evoke lynching souvenirs from the American South — as credits roll over his stomach-churning physical desecration.

What can we take from ALIEN and the decision to make its protagonist a woman in 1979 when such a thing was virtually unheard of in an action film (even if horror was involved)?

I referenced the word implicit a moment ago. The act of casting Sigourney Weaver was in and of itself radical. It imbued all these little moments onscreen, moments that would’ve played entirely differently had a white male actor been cast, with meaning that spoke to women in the audience and, I imagine, more than a few male moviegoers who have been devotees of the series for decades. The story became…you know…feminist.

This meaning is implicit because of the casting alone, but Scott isn’t as successful as George A. Romero at letting Ripley’s gender speak for itself. The choice of a nudie mag as a potential murder weapon is inspired — even if it toes the line between implicit and explicit — but the decision to put Weaver in children’s underpants makes her gender the point (a strip-down not present in Hill and Giler’s script, by the way). It’s a small detail, though, and one that doesn’t come close to undermining the profound impact of seeing Ripley — a woman — kick so much ass and ultimately outlast her male crewmates for two hours of running time.

THE TAKEAWAY

Both NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD and ALIEN defied cultural norms by centering “others” in their stories. Not just centering them, but making them the whole point. The heroes. The good guys everyone in the audience, legions accustomed to only cheering for white men in such roles, would have to contend with. Consequently, these unexpected character/casting decisions changed the original intent of their stories and, in doing so, became game-changing political statements in their cinematic genres and our larger culture.

By juxtaposing these two films, I hope to provide you a new way to consider your own work and your own storytelling decisions. Have you, through a lack of adequate interrogation or even learned biases, prevented yourself from providing your story with daring new narrative horizons?

The mistake would be to assume I’m only speaking about onscreen representation here or arguing for an exciting gender swap to make your hot new take on FRANKENSTEIN more commercial. Sorry, this isn’t a piece about uninspired opportunism. It’s a piece about asking yourself if you’ve looked at your work from all angles…if you’ve challenged the aspects of it that feel most conventional, predictable, tired…if you’ve let the story find a shape that will revolutionize popular film/TV/fiction/comic books in some small way rather than just echo other artists’ innovations.

Because here’s a hard truth: the more things your story is like, the more reasons there are for producers, editors, and audiences to pass on it. I don’t mean you won’t work, but it’s much harder to build a lasting career that way. Moreover, what you do create likely won’t be remembered for decades as NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD and ALIEN have been - and will continue to be.

Read George A. Romero’s screenplay for NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD here, Dan O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett’s draft of ALIEN here, and Walter Hill and David Giler’s draft of ALIEN here.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you: