A Tale of Two (Aging) Heroes: 'Logan' and 'Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny'

Let's analyze the storytelling device that writer-director James Mangold used to provide two iconic characters their cinematic swan songs

A great character introduction can become iconic, but it’s much more difficult to provide an iconic character a narrative exit — a swan song, so to say — that feels like an appropriate conclusion to their story. Filmmaker James Mangold has done it not once, but twice with the films Logan (2017) and Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023). The storytelling device that he used to accomplish these feats is not necessarily unique to him — far from it, in fact — but he happens to do it better than most. By analyzing his use of it, one can learn a great deal about how to develop plots that service your characters rather than characters that service your plot.

OVERVIEWS OF LOGAN AND DIAL OF DESTINY

There be spoilers ahead, kiddos. But you already know that, don’t you? God, I hope you know that. How could there not be?

LOGAN

Logan is the final film in what amounts to a wildly uneven trilogy of films around the X-Men character of Wolverine/Logan (Hugh Jackman). It’s also the final film in the Fox X-Men series in which the character exclusively appeared - at least until the Mouse House bought the place.

The story is set in the near future, one where mutants are on the verge of extinction. Logan — let’s just stick with the titular name — is a broken-down old drunk who drives a limo as a way to pay for the medical care of the neurologically degenerating Charles “Professor X” Xavier (Patrick Stewart). His healing factor is a pale shadow of what it used to be; the adamantium that coats his bones has slowly been poisoning him and death, we sense, is now a painful crawl away. He is a man at the end of everything for himself and his kind, haunted in every waking and sleeping moment by his violent, murderous, beastly past. This has been the central conflict of his existence, in fact – is Logan a man or an animal? Suddenly saddled with a daughter he never knew he had, a child who hasn’t made the same mistakes that he has, he’s forced into a final confrontation with his savage nature.

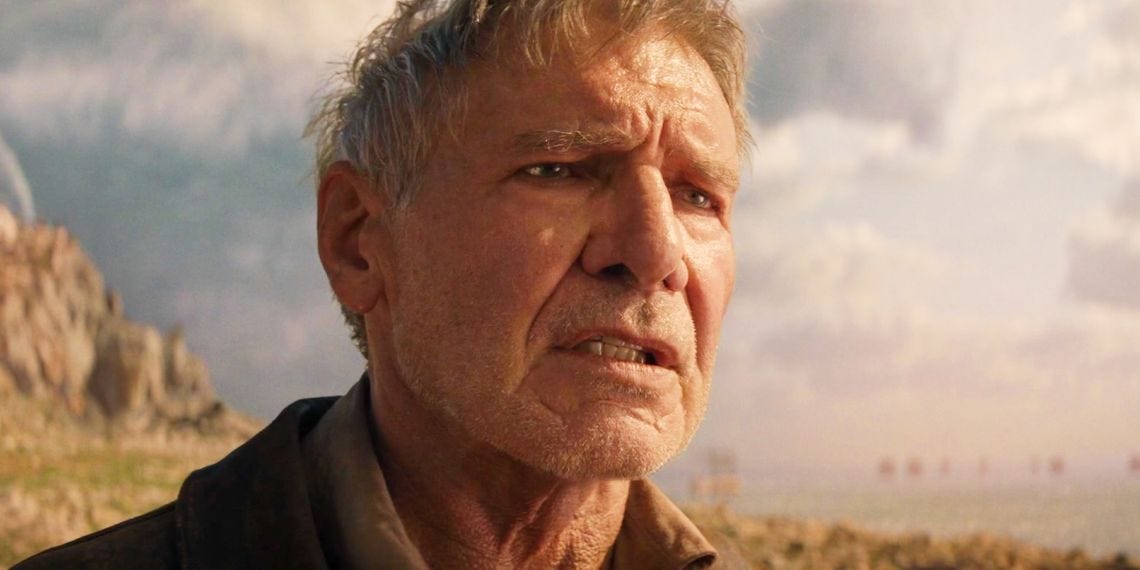

INDIANA JONES AND THE DIAL OF DESTINY

Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny is the fifth and final film in a series that most people were content with ending at three films in. Its predecessor, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull — despite having a title I love — disappointed most fans and, while the film has been reconsidered more favorably as of late, few seem to have recovered from Shia LaBeouf as the famed archaeologist’s son Mutt Williams.

In Dial of Destiny, we find Indiana at the tail-end of his life. It’s the late sixties, the Space Age has made the study of history — and, by extension, archaeology — seem trivial, and his wife Marion (Karen Allen) has left him for reasons we don’t learn until late in the film. His adventuring days are behind him and all that’s left to look forward to is dying drunk and alone in his tiny New York apartment rather than in some exotic locale. But the arrival of his estranged goddaughter, Helena Shaw (Phoebe Waller-Bridge), forces him to come out of “retirement” and chase down the Antikythera mechanism – the titular “dial”, which Helena’s dead father believed could detect time fissures and make time travel possible. In other words, Indy’s MacGuffin in Dial of Destiny is the literal past he has spent his whole life investigating.

THE JAMES MANGOLD WAY

Again, to be clear, we’re not here to discuss a storytelling device that James Mangold actually innovated. But what makes Mangold so interesting is that he used this approach with two different aging movie heroes to tremendous effect and studying what he did is, I believe, hugely edifying to screenwriters at any stage of their craft.

The storytelling device, narrative approach — whatever you want to call it — works in the following manner (which I’m sure will sound reductive, but I want to simplify it as much as possible so we’re all on the same page). It applies to characters’ final acts, such as Logan’s and Indiana’s, but can just as easily be applied to protagonists in general depending on what kind of story you’re trying to tell (there is no universal template for any kind of script, remember).

Identify the general narrative journey your protagonist must go on.

Identify the thematic obstacle your protagonist must overcome. Typically, this means asking yourself: what do they fear the most?

Find a way to dramatize that thematic obstacle in the form of an antagonist - or, if you prefer, nemesis, the arch-enemy, the ultimate rival at this very specific moment in time for your character.

Force your protagonist to confront this nemesis and overcome it in some way or another to resolve their narrative journey.

WHAT THAT MEANS IN PRACTICE

LOGAN

Consider what James Mangold was working with, or rather the story he had to conclude (and here I’m going to switch to present tense, as I think it will be easier to follow things here):

At the start of the story, Logan, his aging titular character, is not afraid of death because he’s lived so long it might even be appealing to him in some way. But he is still afraid that he’s an animal rather than a man.

There are a lot of ways to tackle this theme, sure, but Mangold knows he’s also got to deliver a kind of final redemption story. Not any lazy obstacle will do if he wants to stick the landing here. His best option is to dramatize Logan’s internal conflict, to give his fear a literal physical form, something the mutant can fight claws-to-claws.

Solution: Mangold creates a mindless, savage clone — the animal version of the fabled Wolverine — to hunt Logan down.

The two sides of the Logan/Wolverine character — human and animal — must finally resolve themselves onscreen and the winner will be the true version of the character…which is, of course, Logan.

If you want to dig deeper into all of this, it’s worth considering that the character of Laura/X-23 is also a clone of Logan, but presented as his daughter. She’s the better part of him still, a Young Logan you might say, before the body count maimed his soul. She’s what’s really at stake for Logan. Meanwhile, the other clone is his alter-ego, the savage Wolverine. In short: Logan and Wolverine must battle to decide their mutual daughter’s spiritual fate.

INDIANA JONES AND THE DIAL OF DESTINY

With Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, James Mangold had a bigger challenge than just wrapping up Logan/Wolverine’s cinematic storyline. He had to contend with an actor who was just shy of eight years old and, while still spry, Harrison Ford wasn’t going to be able to play the action hero the way he did once upon a time. Ford had gotten old, which meant Indiana had gotten old, too. Let’s look at how Mangold turned this potential handicap into a narrative strength (once again switching to present tense):

Challenge: Indiana Jones, a legendary adventurer, is on his last legs. Implicit in age is loss and grief. This is a very different scenario than we lost saw the guy, which was getting married to Marion Ravenwood with his son at his side.

Fear identified: Indiana is afraid that with his age and terrible losses he’s become an artifact himself.

Like Logan’s theme, this can be tackled in any number of ways. But Mangold isn’t a hack. He knows this is Ford’s last time at the rodeo. He’s got to send Indiana out with the respect and dignity he deserves with a storyline also appropriate to a septuagenarian archaeologist cum action hero.

Solution: Mangold settles on a time-traveling antagonist who can inadvertently present Indiana with the ultimate choice - become history himself or accept there’s still a lot of life to live.

In the case of Dial of Destiny, this is accompanied by a bit of a narrative sleight-of-hand game to obscure the shocking twist action sequence that helps to conclude the film’s narrative.

First, Mangold brings Nazis back. Nazis are the formative villains in the Indiana Jones mythology. Their presence provokes reflection on his part as well as the audience’s. Everyone is looking backward, which is only appropriate in a film that might eventually involve time travel.

Second, Mangold gives us a physical antagonist in the form of Jürgen Voller (Mads Mikkelsen), a Nazi villain whom Indiana — and the audience — assume wants to go back in time to help Hitler win World War II.

Third, Mangold delivers a character surprise later in Dial of Destiny (that left me crying). At the start of the film, we’re led to believe that Indiana’s wife Marion has left him. But now we discover that it’s actually Indiana who left her – after their son, Mutt, was killed in the Korean War. Indiana’s grief is so profound that he’s given up on everything including his marriage. This is all prompted by Indiana’s goddaughter Helena asking him what he would do if he could go back in time, which creates the nagging suspicion that Mangold intends to give Indiana the opportunity to actually go back in time with the Antikythera mechanism and, in some excruciatingly maudlin finale, save his son’s life. God, wouldn’t that have been awful? (And not just because it would’ve meant having to re-experience Mutt Lang.)

Then comes the final act twist:

Mangold doesn’t send our characters back to World War II and Nazi Germany. He sends them back — way back! — to the Siege of Syracuse in 219 BC where Indiana is confronted by Archimedes and history itself. All his life he’s studied it. But here it is, right in front of him. This is, of course, a metaphor for where he thematically is. He’s an artifact, remember. Or at least that’s his fear, and he intends to prove it by staying in the past as Helena returns to the present. Helena has other ideas about that.

Indiana wakes back in his New York City apartment, surprised to find Marion there. She heard Indiana was back. Is he…back? Of course he is, having faced his greatest fear and come out the other side.

THE TAKEAWAY

Again, James Mangold hasn’t innovated anything here in his approach. He’s simply applied it to two aging action heroes in a way that provides satisfying thematic — therefore character — arc conclusions to two iconic characters. That said, he’s also done it probably better than most filmmakers managed to in both of these examples.

Rather than list other films that have used this storytelling device [cough-cough, Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy], please feel free to suggest others you think have in the comments section below and we can discuss them there.

Logan was written by Scott Frank, James Mangold, and Michael Green; story by Mangold. Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny was written by Jez Butterworth, John-Henry Butterworth, David Koepp, and James Mangold. You can read Logan here; Dial of Destiny’s script is not available online.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy these other ones:

I like this. You made me realize that Harrion's other cinematic alter ego also split with a spouse due to a "dead" son...

die hard Wolverine fan here, and I think LOGAN really got it right.