Vinay Patel and the Temple of Doom: What Should We Do About Problematic Art?

The playwright/screenwriter discusses how his relationship with the second Indiana Jones film has evolved and how to treat other culturally dated and offensive artwork today

In anticipation of the release of INDIANA JONES AND THE DIAL OF DESTINY, I decided to introduce my eight-year-old to the first four Jones films. But when it came to the franchise’s second outing, INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM (1984), I had to repeatedly pause the film to explain to him how what had just happened or what was about to happen onscreen was culturally inaccurate, insensitive, or just outright offensive. In other words: racist. While I had anticipated having to do this, I was surprised to learn that TEMPLE OF DOOM comes with no warning on Disney+ despite how Asian cultures and the Hindu religion are casually reduced to often vile caricatures for laughs and shock value. I found myself yet again wondering how this film came to be and — recollecting a teenage experience of my own related to the film (more on that in a bit) — asking myself what impact it had on Indians and members of the Indian diaspora.

As luck would have it, my friend Vinay Patel emailed me his brilliant new play THE EXPERIMENTAL FILMMAKER to read at pretty much this exact moment — a play about George and Marcia Lucas’s doomed marriage (featuring Steven Spielberg, too) — and, given his obvious passion for the filmmakers behind TEMPLE OF DOOM, the subject inevitably came up.

Vinay is a British playwright and screenwriter. Amongst his many accomplishments, he wrote “Demons of the Punjab” (one of the most celebrated episodes of “DOCTOR WHO”) and, more recently, his sci-fi take on Chekhov’s THE CHERRY ORCHARD was performed at the Yard in London. We first met over lunch at Picturehouse Central in London, and he immediately captured my attention with his ability to nimbly skip back and forth between discussing the kind of art we call high-brow and what we affectionately refer to as geek culture today. Keen, often refreshing observations were lobbed like thought grenades that left me dizzy. Consequently, I was elated when he agreed to discuss TEMPLE OF DOOM and his complicated relationship with it for this newsletter.

The conversation you’re about to read is ultimately about far more than one film. It’s really about problematic art from the past, the messy emotions it provokes in both its fans and detractors, and how we should interact with it today. Vinay’s frank thoughts on the matter are some of the best I’ve ever encountered, and I hope they give you much to consider.

COLE HADDON: Vin, I’m excited to be doing this with you. Typically, these conversations have a more sprawling intention behind them, but with this one, I’m looking forward to a more specific focus – reconsidering a film we both grew up with, from two filmmakers who have significantly influenced us – and, in doing so, getting to know you a bit better in the process.

VINAY PATEL: Thanks for having me! It’s easy for those works that we talk about as influential for us to drift into soundbites, so it’s nice to get a chance to take another look and ask how much of what informed us still sits in our creative instincts – and whether that’s still or ever was a good thing.

CH: Agreed. So, INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM. A…problematic film, I think it’s fair to say. We can get more into that in a moment, but I’m curious when you first saw it.

VP: Hmmm, I’m not sure if I could tell you with any certainty, though it definitely wasn’t in a cinema since I wasn’t born yet. In all likelihood, it would’ve been something I saw when I was six or seven, with my grandmother and grandfather — who lived with us — sat on the floor of the living room because it was closer to the screen. What about you?

CH: I saw it when it was released, in the theater, which means I would’ve been just shy of eight. My father was in the U.S. Air Force and the local air base had a cinema. He took me and my younger brother, whom I remember not being very excited about the exposed beating heart scene. But it was a generally exciting experience in my memory and certainly helped fuel a lifelong love affair with Indiana Jones.

VP: When I think about the Indy films, it feels like I’ve never not loved them.

CH: I feel that deeply. You’re younger than me, so was it even RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK that made the biggest mark on you?

VP: Like, in terms of specifics, it’s probably INDIANA JONES AND THE LAST CRUSADE that most prominently figures in my memory, but it’s that feeling of fun that I always associate with those movies. Also, I’ve written elsewhere about the way my love of STAR WARS was tied to the games around it. With Indiana Jones, there was a LucasArts game called INDIANA JONES AND THE FATE OF ATLANTIS, which is absolutely phenomenal and must’ve been one of the first computer games I played by myself.

CH: I remember it well.

VP: I have no idea how it even ended up in our house. But it meant that, alongside the accessibility of the fun, there was another level of access to that world. As a kid in the suburbs, getting to globetrot in that way, to feel that sense of the world as a canvas was thrilling. Which is why I suppose TEMPLE OF DOOM occupies such a curious place for me - both holding something of that foreign adventure exotica and what I suppose passed as a small element of cultural reflection, which was incredibly rare for me at the time. I wish my grandparents were still here to ask about what they felt about it. I tell myself I didn’t enjoy it as much as the other films, even back then, but it might just have been that we never taped that one when it got shown at Christmas, so I simply saw it less.

CH: I love this detail of you watching Indiana Jones films with your grandparents at Christmas! Was that a tradition in your family?

VP: Not a tradition so much as something that seemed to always happen! Casually slumping in front of the telly at a certain point and discovering the same movies were always on. I’ve joked elsewhere that my entire artistic sensibility has been formed by whoever was programming movies for the BBC in the early nineties. Do you remember when you first had a sense of “wait a minute…” about TEMPLE?

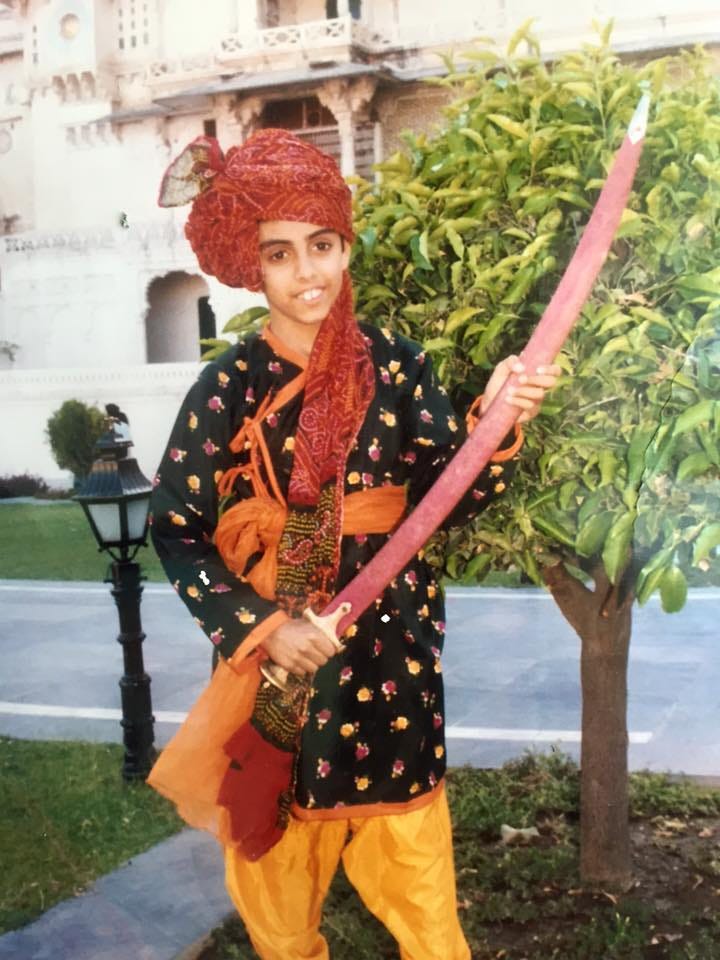

CH: I do! You’ll enjoy it, because it probably illustrates so much of what I imagine concerns you about it. I was sixteen, I assume. Maybe seventeen. Working at a flea market, which I don’t think I’ve ever seen in the UK. Thousands of stalls that just stick around every week. The family next door to where I worked was Indian-born, and I struck up a friendship with their middle child. Young, stupid, utterly unsophisticated because at this point I hadn’t been further away from home than the next state over, I talked about how much I wanted to go to India and try its cuisine. Indian wasn’t a food option when I grew up, not where I lived, so I had assumed what TEMPLE OF DOOM depicted was…you know…authentic. Mind you, none of it scared me. I probably took Indy’s commitment to honoring other people’s cultures too much to heart. The world was something to explore, to try like it was one great big adventure, so I always assumed I’d eventually have to eat monkey brain soup and snake surprise.

CH (cont’d): Needless to say, my Indian-American friend let me know how stupid I was in the politest terms. From that point forward, TEMPLE OF DOOM was always the film in the series I enjoyed because it was Indiana Jones, right? And yet something wasn’t right, and that feeling has only grown worse with every passing year – in fact, it got so much louder when I showed it to my oldest kid recently and spent half the film explaining negative stereotypes about it. I think I added thirty minutes to the running time.

VP: Well, while I wouldn’t call you stupid — politely or otherwise — but I get where your friend’s dismay was coming from. How a group is depicted in a mainstream work has a greater consequence for diaspora/immigrant populations because at least in places where you’re the majority culture, everyone knows a silly representation is exactly that. But for places where you’re a minority and people might not know a lot about you from direct contact, how you’re portrayed in mass media can wind up forming a large part of how you’re understood by others.

CH: From my experience, absolutely.

VP: Having said that, I think your experience reflects the way that art’s role as a conveyer of knowledge and representative of culture has shifted over the last twenty-five-or-so years. How would younger you necessarily have known better or made the assumption that what a film with a character you trusted wasn’t presenting the world in — more or less — good faith? Similarly, when I was younger, the world felt so unknown and I relied on art to tell me what it was like. Now access to information is not just immediate and less hierarchical, it’s overwhelming, and that overwhelm floods back into the past. It can make it seem ludicrous that anyone could look at TEMPLE and feel the ring of authenticity. I suppose, though, you could also make the case that something like TEMPLE existing now doesn’t really matter because the authority of depiction it would’ve had no longer exists.

CH: A moment ago, you said you tell yourself you didn’t enjoy TEMPLE OF DOOM as much as the other two films when you were a kid…but is what you tell yourself true?

VP: Honestly, I can’t really be sure. I suppose I was always more attracted to wonder than dread, and still am. To me, RAIDERS and CRUSADE — especially CRUSADE — made the world seem larger and stranger. A place where knowledge was rewarded but also met its limit. That’s a thrilling philosophical tension. TEMPLE felt like it was more drawn to minutia and the visceral – ripping out hearts will do that, I suppose. Faces get melted and dissolved in both RAIDERS and CRUSADE, so it’s not like they don’t have something of that, but in TEMPLE it’s more action-packed, more cartoonish, and there’s less of Indy’s intellectual, investigative side in it – and that’s part of what always drew me to him. Obviously, I couldn’t articulate it in that way when I was younger, but I suspect, from my adult perspective, that that was something to do with it.

CH: On the other side of how you reacted to TEMPLE OF DOOM as a kid is, of course, is: how has your relationship with it evolved over the years? I can certainly say mine has darkened considerably over the years, even with the quality of the storytelling, which — offensive elements aside — is just confusingly one-note compared to the other two films in the original trilogy.

VP: My feeling is that it’s fundamentally a meaner-spirited movie that wants to punish its characters more than the first. I’ve seen it said that you can tell that it’s a movie made by two men going through a divorce.

CH: It’s an intriguing observation.

VP: The Indy DNA is still in there. There are thrilling set-pieces. Witticisms. Short Round is iconic. But it also has a cruelty in it? The way Indy happily lets Willie have an awful time in the jungle while he plays cards. What I assume is meant to be a disorientated punch into the face of the Cigarette Woman at the start, which you can see is filmed as a gag, but doesn’t feel like one. The direction generally feels less graceful and playful than Spielberg’s other efforts. Also, maybe I’m just dead inside, but seeing Indy rescue some kids doesn’t fill me with joy. He doesn’t care about kids! I know that that’s somewhat the point, I know they needed to throw some tangible stakes in there, but Indy himself always felt to me like the kid cosplaying as an adult and that was plenty for me.

CH: Such an interesting analysis, especially when you consider how Jones behaves in LAST CRUSADE when with his stern, certainly emotionally abusive father.

VP: Ah, yes! I hadn’t thought about that. It’s inevitable, of course, to retrofit our earlier ideas of characters around what we learn about them in later iterations. That relationship between Indy and his father looms so large over the that trio of films for me now. I think that speaks to another difference between TEMPLE and the other two. Both RAIDERS and CRUSADE have the broader quest linked to an emotional relationship in Indy’s life. Marion and her father in RAIDERS. His own in CRUSADE. A challenge to his sense of self. That moment he puts down the rocket launcher because of the appeal made to history in RAIDERS is such a wonderful, unexpected character beat. The way he has to try and understand his father in CRUSADE in order to save the world.

I suppose also, having spoken about how the other movies made the world feel bigger and stranger, there’s a real political and tonal difference between taking what is at least somewhat familiar to Western audiences in Jewish/Christian mythology and riffing off that and riffing off a culture and religion that had less familiarity for that same audience. Does that make sense?

CH: I think so, but, please, keep talking.

VP: Like when I was writing my “DOCTOR WHO” episode about the Partition of India, I would often say that you can make a zombie movie out of World War I because it had a firm place in people’s understanding and so you could play with that. But it’s harder to do that with something people know less about in the first place.

CH: You just referenced your much-celebrated — and brilliant — episode “Demons of the Punjab”. Would the popular onscreen representation of Indians in Western culture — something like TEMPLE OF DOOM — have been on your mind as you worked on it?

VP: For sure. Which is why we went through so many iterations of that episode!

It took a lot out of me and was a real lesson in ambition and humility. I was so determined to add a richness to the understanding of Partition, to deepen and complicate that picture. To move away from the furrow-browed-Brits-in-palaces of it all. To look at areas that had not been served in other depictions.

At the end of the day though, I had to grapple with the fact that the audience this was primarily aimed at knew absolutely nothing about that event in history, so we found our way back to a more 101 place. While it’s inevitable with any script development process, we lost a few things that I’m still gutted about. I’m glad, at least, to have had a chance to include touches like the WWII military service of Indian troops – the largest volunteer army in history – and to make it a story about characters grappling with an extremism that still haunts the subcontinent to this day. Overall, it was a very difficult process but just being able to have this moment of reversal with an Indian character made it all worthwhile.

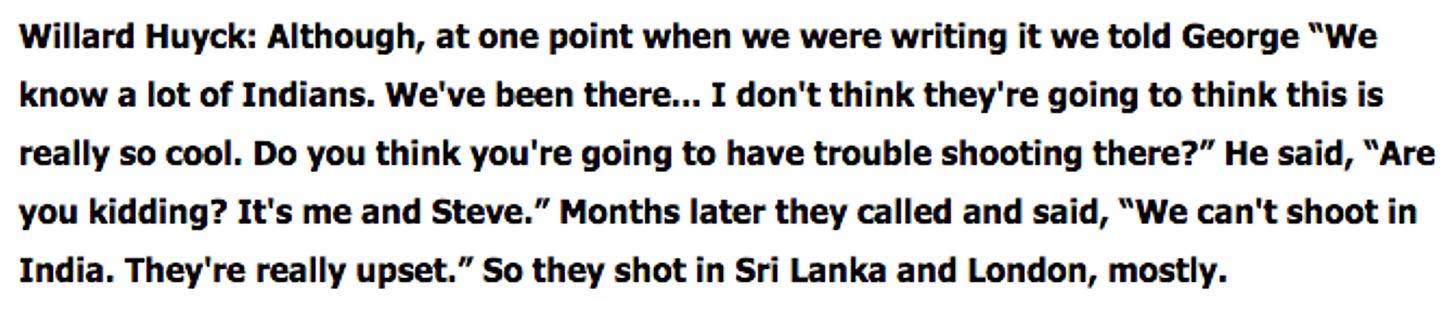

CH: You’ve tweeted and more recently shared with me a fantastic anecdote you found while researching for a play you’ve written on George Lucas’s early years called THE EXPERIMENTAL FILMMAKER. I’m going to include it in the conversation here:

I’m curious, what’s your take on this after recently rewatching the film and this conversation?

VP: That anecdote always makes me howl with laughter. Two of the biggest filmmakers in the world getting a cold dose of reality. Having rewatched TEMPLE, the film’s politics is a little more complex than I remembered it. There is at least an attempt to grapple with British colonialism. It even mentions the 1857 uprising. Indy has some sense of humility before the culture he’s in and speaks the language…sort of. I’ve read that it got banned in India on release, though I can’t confirm if that’s true and I don’t take a government banning something as necessarily indicative of a country’s feelings.

Lawrence Kasdan, who wrote RAIDERS, didn’t want to do TEMPLE because he could tell – as the kids say – that the vibes were off. So, in came Gloria Katz and her husband Willard Huyck who were a screenwriting partnership and had an interest in India. They helped rewrite Lucas’ AMERICAN GRAFFITI and STAR WARS to add character and punchier dialogue to great effect. They’re emotionally attuned, playful writers and you can see the echoes of those efforts in TEMPLE but, to my mind, it feels a little unmoored. A little rushed. Still, I don’t envy anyone having to write a prequel-sequel, let alone to a film so beloved as RAIDERS.

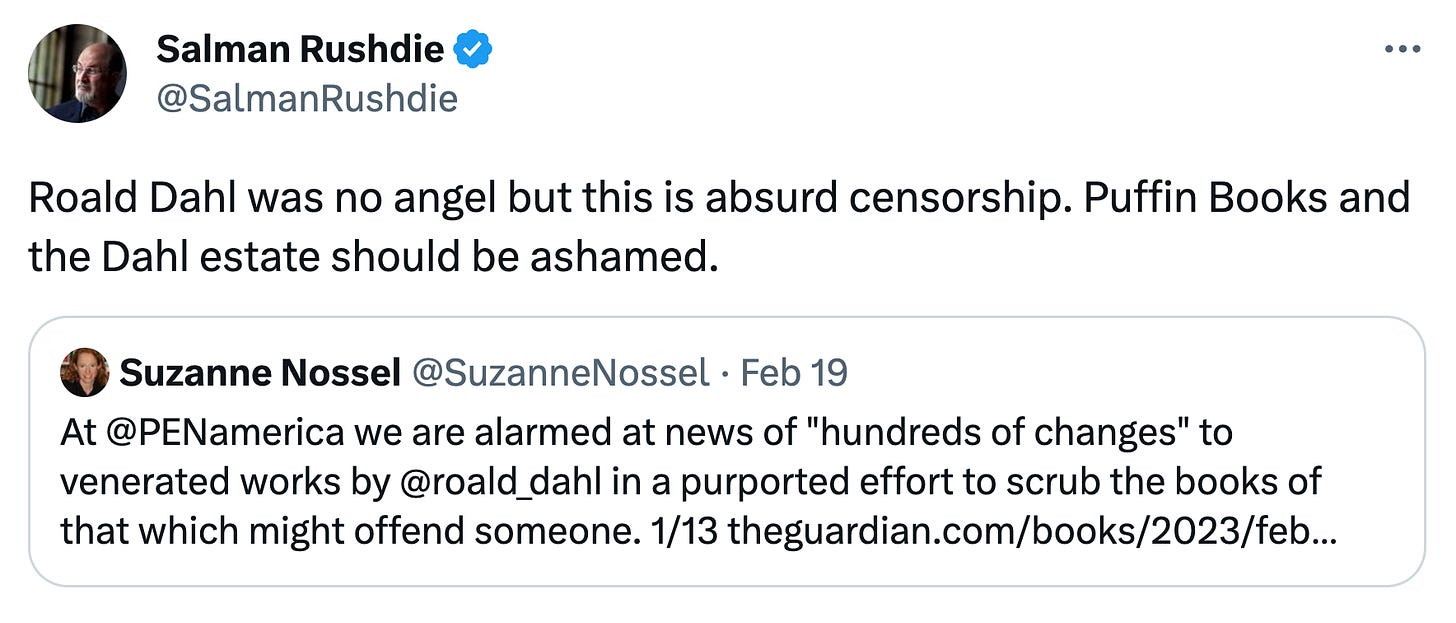

CH: We’re nearing the end of this conversation, I fear, despite how much I’m enjoying it. Let’s go out with a big question. Recently, there was a great deal of outcry – including from me – about Roald Dahl and James Bond books being rewritten to be less insensitive. In the States, university professors are deciding not to teach culturally problematic artworks for fear of student outcry that will get them fired – which has happened many times now, sadly. These are just a few examples, of course. While this conversation you and I are having isn’t meant to provide an answer about how to interact with such art, but I wonder if you have any opinions on the matter, given the film we’re discussing?

VP: Oh boy, I feel like I’m going to regret committing to any answer on this, but I’ll give it a go.

For me, I suppose it’s about what is casual and what is intentional. I think updating the odd bit of language that was not intended with any malice — even though it likely would’ve been hurtful even then — feels fine? I think it’s a bit dishonest though to claim we can keep what’s good about a piece of work and not hold what’s bad. If you can do that, then it comes down to where your personal line is. Like, for example, I don’t think I could work on a Dahl adaptation without a lot of soul-searching because I find the force of his antisemitism impossible to divorce from him as an author and his books are so tied to him as a person. But Spielberg had no problem making THE BFG, though admittedly, he does claim he had no idea about those views before he did so.

More broadly, my POV is always going to be informed by growing up in an area with a strong racist, white nationalist presence.

CH: I didn’t know that about you.

VP: It wasn’t something I could avoid — the mental and physical scars remain — and so naturally my sensibility has run towards wanting to understand such things as a way to push back on them better. I do have a lot of sympathy for people not wanting that to be part of their cultural landscape, and I don’t think making people engage intensely with — arguably — hateful work that definitely costs more for part of a cohort to sit with than others is necessarily productive. On the other hand, I feel anxious about a politics or art that has no curiosity there whatsoever. Am I ducking the question here?

CH: [Laughter] Maybe?

VP: I’ll try to give a straighter answer – I think rewriting [books] is mostly pointless. Make the case for the work if it matters to you. If not, there are other books. So many books! In three hundred years, our shared frames of reference will have shifted entirely anyway, and I don’t think there’s an inherent greatness to any art that means it should forever lay claim to being a cultural keystone. I understand this approach raises the stakes for defending work that’s important to an individual and can lead to a drift towards the path of least controversy…but that is the only way through, I think, that allows for passion and dignity for all. My grand hope is that as more groups feel more confident in their societies, more in command of their representation, the “threat” presented by certain pieces of art diminishes. To bring us back on topic: if TEMPLE was still the only depiction of brown people I, or others, had mainstream access to I would have a bigger reaction to it. Now? It feels almost quaint in how obviously ridiculous it is.

CH: I think that might just be the most intelligent thing I’ve heard or read on the subject, Vin. Thank you for that – and this conversation. Hopefully, it’s given others a lot to think about.

VP: A pleasure! What could be more fun when you’re on a deadline than talking other people’s work? Honestly, though, it was so nice to get a chance to revisit the problem child in a franchise I adore. I’ve come away grateful that TEMPLE exists and just as grateful that we’ve moved on.

Find Vinay Patel on Twitter.

If this article added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

This is really good; thank you.

I'm very impressed with Vinay Patel, at several points, being able to summarize complicated ideas in a simple, direct way.

I grew up with Indy and tried to introduce them to my son (12yo) last year. It was a disaster. His verdict? "A boring mess of a movie." We stopped halfway through. He loved "They Live!" on the other hand.

"I think rewriting [books] is mostly pointless." This about sums it up for me. What's the main reason for editing Dahl (or any other work) to make it "suitable" for a modern audience? Is it because of the words or the money?

Thanks for this insightful discussion.