The 'Tension of Becoming' in Coming-of-Age Cinema

An exploration of liminal spaces in transitional narratives, beginning with three classic films: 'Stand By Me', 'American Graffiti', and 'The Big Chill'

liminal

/ˈlɪmɪnl/

adjective

occupying a position at, or on both sides of, a boundary or threshold.

"I was in the liminal space between past and present"

relating to a transitional or initial stage of a process.

"that liminal period when a child is old enough to begin following basic rules but is still too young to do so consistently"

Our relationship with the future begins to rapidly develop as pre-teens. We’re racked by both impatience and excitement for the change it promises. But we also dread it, develop anxiety around it, doubt it and what it will mean for us. This makes sense, of course; the unknown is something we’re biologically predisposed to run away from. What I’m describing is a kind of existential tension that follows us for much of our life - the tension between what was and what will be.

Let’s call it the tension of becoming.

In this (spoiler-filled) essay, I’m going to discuss how transitional stages of human development have been dramatized on the big screen through three variants of the coming-of-age story. In doing so, I’ll also explore the liminal spaces — socially constructed turning points — that such stories occupy in our lives and culture and the complicated nostalgia they inspire. The anxiety that underpins these films is the most important reason such incredibly time-specific stories remain timeless - because how they make us feel is universal no matter when you were born in the 20th or 21st century.

Part 2 of this essay — “The 'Tension of Becoming' at the End of the World” — can be found here. It discusses the liminal space in which human civilization currently exists, its representation in two artworks that epitomize a uniquely 21st-century kind of “coming of age” film, and how nostalgia has become a dangerous, self-defeating balm. Oh, and Barbie.

YOU’LL NEVER HAVE FRIENDS LIKE THE ONES YOU DID WHEN YOU WERE TWELVE

You’re nine years old. Or maybe eleven. Maybe thirteen, your body changing even faster than the world around you – not that you’d notice because the rest of the world doesn’t exist for you yet. Life will never be this good again, this free, this pointless…this endless. You don’t realize it yet, but this will be the time in your life you regret the most, or is it that you’ll regret that you can’t remember it better? Returning to it, the simplicity of it, the innocence of it, before the hurt and disappointments and confusing contradictions of adulthood blow it all up and make it forever an impossible dream, will seems altogether impossible years from now. All that will remain are stories, stories about the good times, the bad times that somehow never seemed as bad as they do in hindsight, and that moment — that terrible, heart-breaking moment — when it hit you, hard as a fist, that everything was going to change. When you glimpsed the truth of what was coming your way like headlights bearing down on you in the dark…

The coming-of-age film is a big tent, in that a lot of different kinds of stories about “growing up” fit into it. Two of my favorites in recent years are Boyhood and Moonlight (2016), but both of these films involve sweeping periods of narrative time, even into adulthood, and so, I think, muddy the conversation I want to have here. They’re just too epic. What I’d rather focus on instead are stories specifically about children and fixed in very specific moments in time - often told over a few days or, possibly, a few months. Some examples that immediately come to mind are The 400 Blows (1959), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Crooklyn (1994), Wadjda (2012), and Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. (2023) – but it’s Stand By Me (1986) that I’m going to dig into because I think it illustrates the tension between childhood and adulthood, of becoming, more dramatically than most thanks to a clever framing device.

The film Stand By Me was written by Bruce A. Evans and Raynold Gideon, who adapted it from Stephen King’s short story The Body. Set in 1959, it tells the story of four boys who try to seek local fame and fortune by finding the dead body of a missing boy. But what it’s really about is being twelve years old, still a kid but old enough to recognize that the adult world is confusing as hell, terrifying even, and many of the people who populate it seem to be broken, shuffling around like survivors of the Blitz, looking for something you’ve never thought it important enough to care about. In other words, it’s about that time in your life when you can’t grow up fast enough, but you’re completely unprepared for the reality of what you so badly want.

Now, it’s easy enough to focus only on the surface of what’s happening in Stand By Me, which is kids trying to work out what adulthood means on the page and on our screens. King found an interesting — and, in his style, violent — way to express that in a setting and time familiar to him. The filmmakers then used the visual language of cinema to conjure warm nostalgia for America’s Golden Age (or rather, the myth of its golden age). Not a head-scratcher, right?

Except Stand By Me only works as well as it does because of the tension that’s implicit in every scene of the film. A tension between what was and what will be. What does this mean? Well, imagine the four friends in a game of tug of war with the four adult versions of themselves. They grunt and scream and fight with everything they have in them to hold out just a little bit longer, but inevitably they are pulled, inch by inch, toward inevitability. This is how the film plays out, each scene another inch surrendered to the next chapter in their lives. There is no winning. Nothing will ever be the same, which is why the film’s concluding narration, uttered by a grown-up version of one of the characters upon reading about the death of one of his old gang, hits so goddamn hard.

"I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve. Jesus, does anyone?"

SCHOOL’S OUT FOR SUMMER!

Tonight’s the night. You’re seventeen, and there’s no way anyone can tell you otherwise anymore - you’re an adult now. An adult! You can drive, you can get drafted into war, and you can buy high-caliber killing machines. Unfortunately, you still can’t buy booze and get drunk with your friends, at least not legally, but you’ll find a way to get around that because you’ve graduated and, woo-hoo, it’s time to party. Everything changes tomorrow. Tomorrow, there will be responsibilities. Like, what to do with your life. College? Four years in the military? A job at the local factory where your dad broke his back? Now that you think about it, shit, tomorrow sucks. Tomorrow sounds like your parents. That makes tonight your last hoorah. For one night and one night only, you’re both a kid and an adult. You’re dry-humping the line that divides the two. If you get lucky later on, maybe you’ll even get to hump an actual human being. Because tonight’s the night!

There are three main sub-groups of the “growing up” coming-of-age story: the turn from adolescence to teenager, the turn from teenager/young adult to full-blown adult, and the escape from arrested development. For example, Stand By Me is about the turn from early childhood to teenage life (even if it’s adulthood that’s really on the other side of the emotional narrative).

Next up are films about young adults colliding headfirst with the emotional and practical reality of adulthood. In most cases, these stories take place over several days or, at most, a few months. Examples include Rebel Without a Cause (1955), The Graduate (1968), Cooley High (1975), Boyz n the Hood (1991), and Lady Bird (2017).

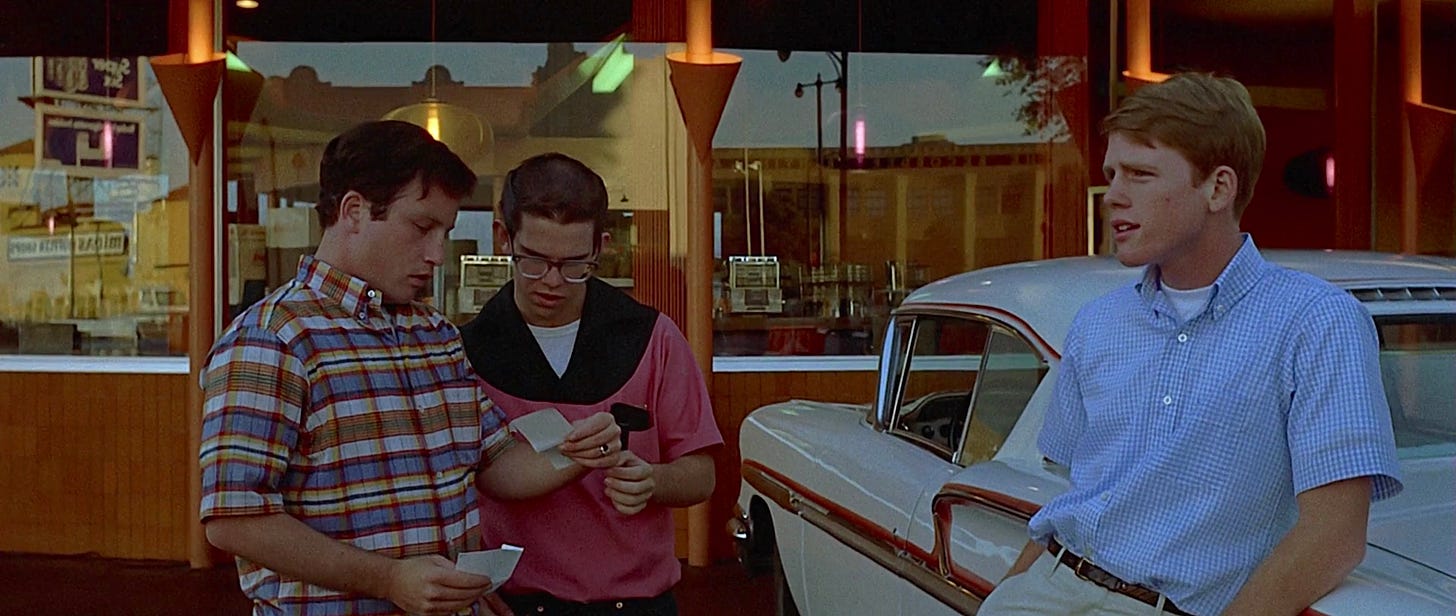

But I’m going to focus on an even more specific corner of this sub-group - goodbye-to-high school films as told in one amazing, life-changing night. Some examples of what I mean by this are Dazed and Confused (1993), Superbad (2007), Booksmart (2019), and the film that made George Lucas such a success that he was able to get Star Wars: A New Hope made – American Graffiti (1973).

Set in 1962, just a few years after the events of Stand By Me, American Graffiti takes place in Modesto, California where Lucas grew up and spent his high school days cruising the town’s main street on the weekend and racing cars. Not coincidentally, that’s what the film is about, or rather the impending loss of that aimless freedom. Four male friends have just graduated high school and are now staring down what comes next for them: Curt and Steve intend to go away to college together; John is a gear-head who knows his prospects are so poor his only option is to metaphorically try to stay ahead of this truth in a street race; and Terry/Toad who can’t think of anything except getting laid.

At its heart, American Graffiti is not as cynical about “growing up” as Stand By Me (at least not until the film’s postscript about the character’s futures). There isn’t talk of Vietnam or whether the friends will become as ugly and abusive as their parents might have been. There’s no meta-commentary about the dark turn the Seventies is going to bring to America, though the “good times” of this film feel even more nostalgic — and fanciful — because of the reality of the decade in which it was released. No, the friends are just scared of letting go of the only lives they’ve ever known as exemplified by the joy found on the local cruise strip. You might even say they’re already nostalgic for it.

The fear I’m describing is especially dramatized in the character of Curt (Richard Dreyfuss) who, with his friend Steve (Ron Howard), is getting on a plane to college tomorrow morning. This is their last night of freedom, as they see it. Except Curt is having second thoughts. He sees what he’s saying goodbye to, what he’s trading for the unknown, and he convinces himself it’s a mistake to go. A fantastically beautiful blonde, an unattainable figure who keeps slipping away in her white cruiser, comes to represent his salvation from this mysterious future. If he catches her, it’ll all be okay. Except he doesn’t, and he decides to board the plane the next morning as planned. Ironically, it’s Steve, the one most vociferously committed to leaving, who abandons his out-of-state college plans; he’ll instead go to the local college so he can marry his high school sweetheart and become a boring replica of his parents.

If there was any chance of you leaving the film feeling good about what you left behind in high school, who you were, who you’ll never be again, Lucas slaps a postscript on his film to gut-punch you with a healthy dose of reality (that mostly gets lost in the nostalgic glow American Graffiti generates in many viewers):

In 1964, John was killed by a drunk driver; in 1965, Terry was reported missing in action near An Lôc, South Viet Nam; Steve is an insurance agent in Modesto; Curt is a writer living in Canada.

YOU CAN’T ALWAYS GET WHAT YOU WANT, BUT…

Fuuuuuuuuck, this wasn’t the way any of this was supposed to go. You had all these ideas about the adult you were going to become, but when you look at that mirror today, at who you ended up…wow, seriously, what the hell happened to you? Maybe it’s the career that didn’t work out, maybe it’s the marriage, maybe it’s the kids who make you regret them every single time they refuse to put their shoes on for school. Maybe it’s the ideals you traded for the six figures, maybe it’s the world that’s burning down outside your windows, maybe it’s the sad realization that all the booze and pills and social media posts advertising how happy you aren’t going to ever make you happy. Maybe it’s just you. Except it’s not. It’s everybody else you know, too. Everybody is stuck someplace between what was and what they were supposed to become, just trying to get through tomorrow while endlessly thinking about the past, and maybe that’s all you were waiting for all those years - to end up as stuck, as meaningless, as miserable as your parents were. Fuuuuuuuuck.

The third kind of coming-of-age film I want to discuss concerns, counterintuitively, full-grown adults who have to escape their arrested development. It’s a sub-group of “growing up” films that I haven’t seen discussed much in cinematic history, but what it pertains to are adults who are similarly stuck in a liminal space between two points in their lives – and they’re stuck in that position because adulthood proved too much for them in some way or another. Examples include Return of the Secaucus 7 (1980), Diner (1982), Reality Bites (1994), and Beautiful Girls (1996) - and The Big Chill (1983).

For starters, the arrested development coming-of-age film is a label that can be erroneously applied to many kinds of dramas that I wouldn’t necessarily describe as such because this sub-group of “growing up” story always involves groups of friends reuniting in some effort, conscious or otherwise, to hold on to or recapture their past in some way. What this typically means in practice is a lot of naval gazing and whining by white people as they try to work out why they’re so disillusioned about the lives they’ve accidentally created for themselves. This is also why the arrested development coming-of-age film doesn’t have a lot of great examples in the 21st century - because this kind of cinematic story reached its cultural zenith during the Eighties and Nineties when white affluence and privilege was so relatively extreme that moping about lost ideals and hope, as in The Big Chill, rather than the actual societal cost of those lost ideals and hope seemed completely reasonable.

The Big Chill was written by Lawrence Kasdan and Barbara Benedek and directed by Kasdan. A group of Boomers who lived together in college (at my alma mater, in fact) reunite after their friend commits suicide. It’s the first time they’ve all been together in fifteen years, which allows them to reckon with the mystery of why their friend slit his wrists in the tub downstairs, as well as with the adults they’ve become. They do this to a soundtrack of Motown and rock-and-roll, the music that provided the soundtrack to their college experience, making the tension between nostalgia for their pasts and the present/future they are stuck in/with that much more surface.

The Big Chill is about people who are haunted by the fantasies of themselves that they constructed in college. These were anti-establishment radicals forged in the late Sixties and early Seventies. They were going to make a difference. They were going to change the world, goddamnit. Instead, they compromised their ideals so much that they’re now ashamed of themselves - even as they enjoy the fancy homes and nice cars “growing up” earned them. But on this weekend, they’re going to have to deal with all that baggage, call bullshit on each other, on themselves, and grow the fuck up for real.

Well, in theory.

By the end of the film, everyone has made life decisions, some of them shockingly dramatic, but there’s also the very real sense that they’ll end up right back here or somewhere similar in another fifteen years wondering where everything went wrong for them again. That’s the irony of arrested development films like The Big Chill - they reveal that after spending the first two or so decades of your life fixated on the future, what being an adult really means is spending the rest of your life mourning the loss of those first two decades.

There’s a dark side to this aspect of human development, or human nature if you prefer that. As the 21st century becomes more incomprehensible and our future in it more tenuous, the past becomes a refuge. Nostalgia for “simpler times”, when everything was black and white — even if we have to rewrite history to provide that kind of comforting fantasy — takes on the role of narcotic with terrible cultural and societal consequences. I be discuss some transitional stories that this new spiritual arrested development has inspired in “The 'Tension of Becoming' at the End of the World”, which you can read here.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Thank you, Cole, I really enjoyed this. Stand By Me and American Graffiti are both films that I loved in my teenage years (and still do) and I like this take on them. I find it a weird coincidence that Richard Dreyfus is the one example of four friends in both films who can be seen to have made a successful transition to adulthood, and as a writer no less!

Great article. I’ll read Part 2 next. Interestingly (or not), that the three movies you highlighted, as well as most of the others mentioned as example that I’ve actually seen (To Kill a Mockingbird being a notable exception), were not films I enjoyed. Maybe because Stand By Me and American Graffiti were so male-centric and The Big Chill was too whiny for me? Maybe it was the age I was when I saw them? I’m sitting here trying to think of what coming-of-age movies impacted me, and I’m at a loss. I’ll keep thinking!