The 'Tension of Becoming' at the End of the World

In this exploration of liminal spaces in transitional narratives, we discuss the novel 'Station Eleven', the films 'Children of Men' and 'Barbie', and Hollywood's ‘cinema of denial’

What’s the point? It’s the question you ask yourself when you wake up every morning and find yourself wandering through the wreckage of the world on your phone’s screen. You don’t know what’s worse - the fact that you can still remember what it was like to have hope or the fact that what’s happening outside makes that old you look like such a chump. A sucker. A fool. It was always going to end like this. It was always going to end. So, why not shamble to the bathroom, search through the prescriptions you use to make it through every day, and shove a few handfuls of them down your throat? Except you brush your teeth instead and head into work like you did yesterday - a bad habit you can’t give up. Or is it…something else? Once upon a time, you tried to fight back the seed of dread rooted in the back of your mind, screaming about change. Now, there’s only the dread and a glimmer of light flickering in the darkness of your imagination. A glimmer of hope. It’s all you have left despite how futile even the idea of it seems now.

How’s that for a depressing way to start an arts essay? But if you read “The 'Tension of Becoming' in Coming-of-Age Cinema”, which I recently shared, then you might understand the point of this deeply subjective, second-person introduction. The goal is to put you in the emotional mindset of a specific kind of “coming of age” story. Last time around, I did something similar as I discussed films about the turn from adolescence into teenager, the turn from teenager into adult, and the “arrested development” that occurs when (typically white) adults confront the fact that they hate the people they’ve become and struggle to find a way forward. Today, though, I want to discuss a very 21st-century evolution of the coming-of-age story. These are stories about characters — but, really, our civilization — collectively stuck in a kind of spiritual arrested development brought about by the “end of the world”.

Coming-of-age stories are, at their core, about characters struggling to escape liminal spaces. What this means is characters who exist at or — or on both sides of — a boundary or threshold. Liminal can also suggest being at the transitional stage of a process. So, let’s just call them stories about characters who exist neither here nor there, torn between who they were and who they are becoming.

But in the 21st century, humankind finds itself stuck in an unprecedented liminal space between the world it has generally known since its cultural ascension and the new one that is rapidly replacing it. This existential crisis has given rise to what I call cinema of denial built around providing and taking refuge in the past. Nostalgia for “simpler times” when everything was black and white — even if we have to rewrite history to provide that kind of comforting fantasy — takes on the role of narcotic with terrible cultural and societal consequences.

Such cinema of denial — which much of Hollywood’s big-budget big-screen output over the past fifteen years would qualify as — bears little to no resemblance to the world around us today because it refuses to recognize the most pressing issues facing civilization.

In this spoiled-filled essay, I’m going to explore two post-apocalyptic works that directly confront the terrifying liminal space within which humanity is currently flailing (Emily St. John Mandel’s novel Station Eleven and the film Children of Men), the cinema of denial that is helping us pretend our existential crises away, and what the film Barbie has to say about all of this.

Yes, Barbie.

My hope is to provide you with an alternative way to understand the decline of American cinema in the 21st century, but also civilization itself and how we experience and understand our world and future as a result.

(NOT) LEAVING ON A JET PLANE

Station Eleven was published in 2014, the fourth novel from Emily St. John Mandel. It’s set in the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada before and after the “Georgian flu” wipes out more than 99% of humankind. The stories of several characters are interwoven across time, both in the years leading up to the mass extinction and the two violent, hard-scrabble decades that follow it. In between its beautifully well-drawn character studies, it ponders heady questions about the value of what we’ve built as a civilization, what we would want to preserve if it collapsed tomorrow, and how far we would go to safeguard its remains.

The mosaic of disparate characters is connected across the years by items that possess symbolic literary value, a two-of-a-kind graphic novel called Station Eleven, a theater troupe’s tour circuitous route, and, most importantly to this essay, a (fictional) airport.

Severn City Airport, to be precise.

An airport as anonymous as any other, banks of windows and fast food and ventilated air that tastes like plasticized sweat, where people always seem to be coming and going…stuck neither here nor there…until the world stops and it becomes survivors’ home.

The made-up name Severn City feels appropriate to the region of Canada where it is located. So many locations there are named after British locations - in this case, the Severn River. But the name Severn, the meaning of which has long been forgotten by history, also evokes the word “sever”.

sever

/ˈsɛvə/

verb

divide by cutting or slicing, especially suddenly and forcibly

This is not unintentional. An airport, a place between worlds, located in a novel about before and after and what, if anything, comes next.

THE WAITING PLACE, PART 1

The third type of coming-of-age film I described last time around was about arrested development. About the emotional arc of adulthood coming to a screeching stop. Self-doubt, regret, and crushing disappointment leave characters standing still. Very typically stuck in a liminal space between their youth and a culturally constructed turning point of adulthood such as a ten-year high school reunion or middle age. The resolution is always to grow up...except, you know, for real this time.

But there’s a variant of this that has manifested in the 21st century as humanity’s old debts with Mother Earth finally demand payment - spiritually arrested development, in which stunted characters spend their time looking forward with confusion and despair rather than backward at what they’ve lost.

And there is no finer cinematic example of this than Children of Men (2006).

Adapted (loosely) from P.D. James’s novel The Children of Men (1992), this masterpiece of dystopian cinema was written by director Alfonso Cuarón, Timothy J. Sexton, David Arata, and Mark Fergus and Hawk Ostby. It opens in 2027 with the news of the stabbing death of the youngest person in the world - an eighteen-year-old kid. This makes sense only because no human has given birth in eighteen years, which means every person in the film, everyone drifting past in the background, is living through the literal end times. No hope of change. Just slow decay and eventual death as reflected in the environment that is likewise calling it quits in slow-motion thanks to human civilization.

If coming-of-age stories are typically about being impatient to grow up, Children of Men is about being impatient to go extinct.

Our protagonist is Theo (Clive Owen), a former activist turned apathetic nobody after the death of his young son many years earlier. He’s so emotionally divested from his and our existence that he exploits a terror attack he witnessed to just get out of work, the actual event of no consequence to him. What he doesn’t understand is that he’s about to become the guardian of a pregnant woman, the mother of a potential messiah for humankind, and it will require him to embrace hope again regardless of what it costs him.

Children of Men is, as far as I’m concerned, one of the greatest films of the 21st century. On some days, I believe it’s the greatest, or at least its most important. Sometimes, both. Its bleak, prescient view of the future, informed by hard science beyond the central reproductive conceit, startled people upon its release. The Oscars all but ignored it. But with every day that passes since then, its significance explodes exponentially. While our reality is not playing out exactly like the film’s, it never the less reflects the existential truth of Cuarón’s magnum opus. We are living during one of the greatest mass extinctions in the Earth’s history, and yet humanity seems preoccupied with everything except the one thing that will make all of its other concerns seem relatively petty by comparison.

The character of Theo — a man who has to be initially bribed to even help do what’s right — isn’t just Children of Men’s protagonist. He’s a surrogate for our spiritual malaise, our disinterest in our own demise, our willingness to consciously pretend away inconvenient truths.

There’s a scene early in the film in which Theo visits his posh cousin Nigel (Danny Huston) who is responsible for saving artworks from around the globe. Nigel lives with Michelangelo’s David in his living room and Picasso’s Guernica hanging on his dining room wall. Theo asks Nigel, “A hundred years from now, there won't be one sad fuck left to look at any of this - what keeps you going?” His cousin replies, “You know what it is, Theo? I just don't think about it.”

“I just don’t think about it.”

THE WAITING PLACE, PART 2

If you have children, there’s a decent change you’ve read Dr. Seuss’s The Waiting Place to them. I thought of this book often as I recently re-read Station Eleven.

Waiting for a train to go or a bus to come,

or a plane to go or the mail to come,

or the rain to go or the phone to ring,

or the snow to snow or waiting around for a Yes or No

or waiting for their hair to grow.Everyone is just waiting.

And this is from Chapter 42 of Station Eleven:

At first the people in the Severn City Airport counted time as though they were only temporarily stranded. This was difficult to explain to young people in the following decades, but in all fairness, the entire history of being stranded in airports up to that point was also a history of eventually becoming unstranded, of boarding a plane and flying away. At first it seemed inevitable that the National Guard would roll in at any moment with blankets and boxes of food, that ground crews would return shortly thereafter and planes would start landing and taking off again. Day One, Day Two, Day Forty-eight, Day Ninety, any expectation of a return to normalcy long gone by now, then Year One, Year Two, Year Three. Time had been reset by catastrophe. After a while they went back to the old way of counting days and months, but kept the new system of years: January 1, Year Three; March 17, Year Four, etc. Year Four was when Clark realized this was the the way the years would continue to be marked from now on, counted off one by one from the moment of disaster.

CINEMA OF DENIAL

You can come up with other explanations as to why Children of Men failed to find greater success when it was released, but I find it difficult to take any of them that seriously when you consider how many other efforts by Hollywood and artists around the world have also resulted in financial disaster. Time and time again, any attempt to discuss climate disaster and the current mass extinction in film or television fails to find an audience. People just don’t buy tickets or tune in, which one can easily understand to be the popular disinterest in real-world apocalypses rather than the fictional ones we prefer to entertain us on our screens.

Ask yourself when the last time a big-budget film of any kind even acknowledged Earth’s current ecological crisis or, hell, even the political slide away from democracy. Yes, there are exceptions, but typically only if they’re wrapped in so much spectacle that audiences have to work to identify the parallels to our own experiences (such as the Avatar series).

The fact of the matter is, today’s audiences are, by and large, stuck - between what was and what will be.

We don’t know how to escape what’s coming, and so the only reasonable options appear to be to retreat into older, more familiar forms of experiencing existence to help us bear the fact that we will all die in a world completely unlike the one we were born into and our children, in turn, will die in one completely alien to us. What I mean by this is endless reboots/sequels/requels. Consider U.S. studios’ 2024 theatrical release schedule. To look at this graphic is to feel ten again, at least for me.

The television landscape similarly suffers, though to a lesser degree. Consider how many TV series from decades ago are now being regularly resurrected, from “Murphy Brown” and “Mad About You” to “Will & Grace” and “The Conners” - and even “Night Court”, a series that first debuted in 1984. Fans have been clamoring for a “Friends” reunion for years, and I have no doubt Warner Bros. had offered the cast hundreds of millions before Matthew Perry’s untimely death. But there’s one series that has long been discussed that will never return to the small screen for good reason - “The West Wing”. A reunion series would have to collide head-on with a reality that makes its (wonderfully warming) neoliberal fantasy seem even more preposterous today. Even an attempt to outright reboot it wouldn’t make sense in 2024.

Then there is the matter of superhero films, which have largely defined 21st-century American cinema - and yet to watch these would lead you to believe they’re being made for a 20th-century audience with 20th-century concerns.

To be clear, I’m a fan of superhero films. I don’t need them to go away, as much as I need the dominant Hollywood film genre to respond to our world with more than passing, blink-and-you-missed-it effort. And most of the time, even if they make such an effort, its dimensions are so blunted, its edges sandblasted away to avoid anything like controversy or further dividing already riven audiences, that their efforts feel more embarrassing than illuminating.

In the MCU, for example, there is no climate crisis or poverty, sexism and racism were non-existent for more than a dozen films and even then was mostly presented with kid gloves, and even when Nazis did show up, they were called Hydra and white supremacy is conveniently no longer part of the organization’s mandate (in fact, you can’t even tell what they really want as that would require a political ideology audiences might have an opinion about). When our heroes finally experience a “civil war”, it’s about vague ideas like “freedom” and “security”, not liberal and conservative ideals or even democracy and authoritarianism.

Marvel’s Black Panther (2018) is a rare counter-example to this argument. It’s one of the bravest films Hollywood has produced in the past fifteen years and certainly one of the most confronting about race ever produced there in how it delivers its attack on colonialism via a big-budget superhero film. It’s the definition of helping the medicine go down with a spoonful of sugar. The point is, the genre is capable of more, but its manufacturers — the studios behind them — would prefer to keep its audiences as unconfronted, as safe, as secure in its black-and-white understandings of the world as possible.

If you’re still not sure about my argument here, ask yourself how many Marvel or DC superhero films produced in the 21st century couldn’t be screened for an audience from 1982 or 1994 with almost no aspect of their narratives being changed (except maybe computers and cellphones). They exist outside of time, largely irrelevant to the world we are currently living through, offering us no tools to navigate today or tomorrow or even better understand the histories that inform our present and future. This is at the heart of Martin Scorsese’s complaint about superhero films, but really Hollywood franchise filmmaking today. This divestment from our reality concerns him, not the existence of superheroes. It concerns me, too.

Again, I don’t want superhero films to go away. I believe they can be great cinema and, even when they’re not, they still offer valuable entertainment as they have for half a century. But the Hollywood ecosystem they are being created in today is broken as few other options are being provided to audiences. What we’re left with is a large number of films that act as sociological security blankets, all too often there to foster our collective ignorance of our present existence by narcotizing us with how we think of and feel about the past.

Karl Marx said religion is the opiate of the masses, but it’s been replaced by nostalgia today - and the drug is laced with cyanide this time.

THE MEMORY OF FLIGHT

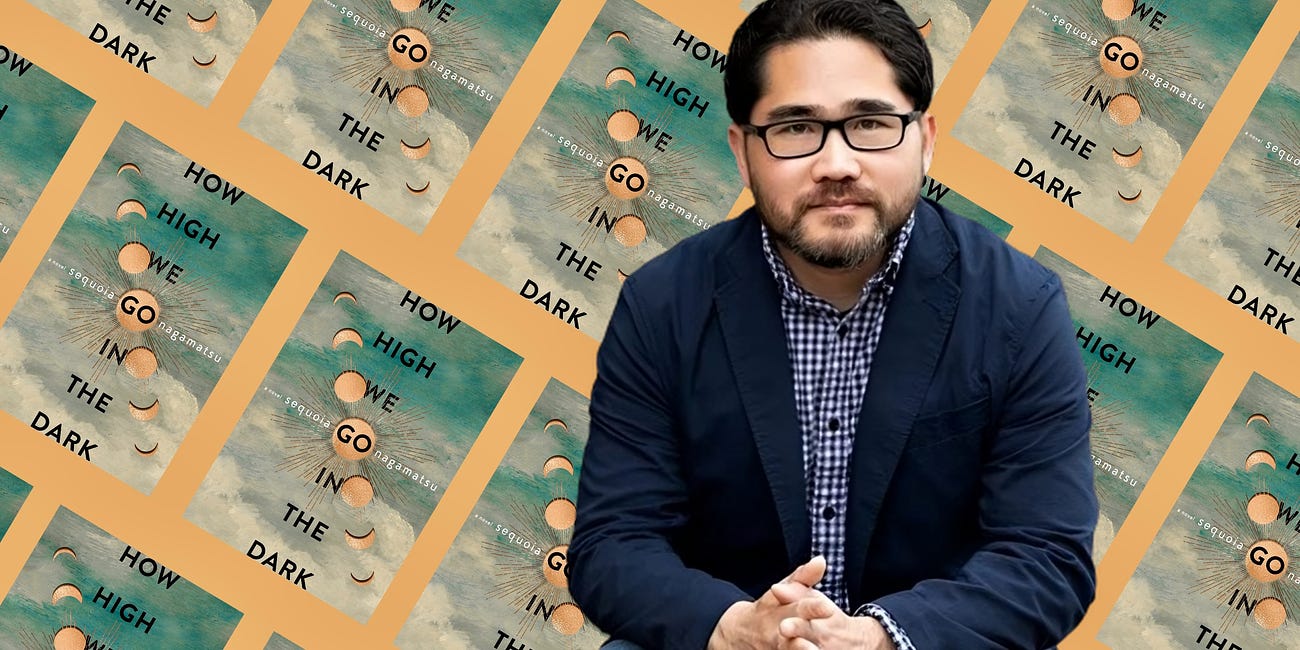

Fiction and other mediums certainly do much better when it comes to confronting the existential anxieties of the 21st century and, in particular, our climate crisis and the religion of capitalism that has fueled it and a rapidly growing number of nations’ slide toward fascism. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006) and Richard Powers’s The Overstory (2018), both Pulitzer Prize winners, immediately come to mind. Sequoia Nagamatsu’ How High We Go in the Dark (2022) does, as well, a book so beautiful I had to interview its author for one of my artist-on-artist conversations. My own debut novel, Psalms for the End of the World (2022), similarly attempts to confront the uncertainty of our reality today. There are many others I could tell you about, several of which are also fixated on our current liminal existences, but Station Eleven expresses this state more poetically than most. This passage is from its Chapter 44:

In the old days he'd taken quite a few red-eye flights between New York and Los Angeles, and there was a moment in the flight when the rising sunlight spread from east to west over the landscape, dawn reflected in rivers and lakes thirty thousand feet below his window, and although of course he knew it was all a matter of time zones, that it was always night and always morning somewhere on earth, in those moments he'd harbored a secret pleasure in the thought that the world was waking up.

CINEMA OF THE REAL

In some mind-bending twist, Barbie (2023), a film inspired by a toy line — a toy line! — is one of the realest Hollywood films made in many years. It’s also a tear-inducing coming-of-age story.

Written by Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach and directed by Gerwig, it makes Stereotypical Barbie (Margot Robbie) one of the great movie heroines. Barbie lives in Barbieland, a fantastical paradise where a legion of Barbies run everything, every day is the perfect day, and men exist for no other purpose than to amuse the Matriarchy with their hot bods and empty personalities. The interesting thing about this existence is that the Barbies know they are allegorical manifestations of toys that are popular with little girls in the Real World and believe their independence, great houses, and supremacy in the workplace inspired a feminist revolution there. The irony, of course, is the opposite is the case and the Mattel corporation in the film actually uses Barbieland to suppress women’s freedoms in the Real World. Girls play with the toys and develop problematic ideals for themselves, which keeps the Patriarchy — including the all-male Mattel Board — in power. By the end of Barbie, the neat, ordered fantasy of Barbieland must reckon with the sexism, misogyny, and chaotic disorder of the Real World.

This is all part of Stereotypical Barbie’s coming-of-age story.

Barbie is a toy. An unrealistic “ideal” of the female body in the media. She has no nipples, no genitalia. She doesn’t even have a gender except the one she was assigned by Mattel. But through the course of the film, she discovers she’s essentially been living in a manufactured lie - in a kind of adolescence appropriate to the emotional development of a child (which I would argue is an apt description of the Patriarchy represented in the film and which we are all still trapped in today). While that lie can be comforting, it’s still a lie. Reality — the real world — is far messier and, while it may be hard to navigate, that’s what growing up means.

By the end of the film, Barbie gets to make the choice to identify and live as a woman. Toys are great and they can be fun. They can inspire little girls to embrace freedoms for themselves they couldn’t have had a century ago, they can change how little boys think about themselves and the world engineered over centuries to benefit them, and they can provide us all wonderful distractions from anxiety about what exists outside our doors. But sooner or later, you have to put your toys away and go outside and live in the real world.

LET THERE BE LIGHT

One of the reasons Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven has resonated with so many readers is its relatively unique interest in confronting humankind’s greatest existential crisis and imagining how we might spiritually find our way through it. It suggests art, in particular, could play the vital role of light in the darkness - but the metaphor nevertheless takes on a more literal presence in the story as it approaches its conclusion.

From Chapter 51 of Station Eleven:

"Look there," Clark said, to the south. It's what I wanted to show you." [Kirsten] followed the line of his finger, to a space on the southern horizon where the stars seemed dimmer than elsewhere in the sky. It appeared a week ago," he said. "It's the most extraordinary thing. don't know how they did it on such a large scale."

"You don't know how who did what?"

"I'll show you. James, may we borrow the telescope?" James moved the tripod over and Clark peered through, the lens aimed 1st below the dim spot in the sky. "I know you're tired tonight." He was adjusting the focus, his fingers stiff on the dial. "But I hope you'll agree this was worth the climb."

"What is it?"

He stepped back. "The telescope's focused," he said. "Don't move it, just look through."

Kirsten looked, but at first she couldn't comprehend what she was seeing. She stepped back. "It isn't possible," she said.

"But there it is. Look again."

In the distance, pinpricks of light arranged into a grid. There, plainly visible on the side of a hill some miles distant: a town, or a village, whose streets were lit up with electricity.

GO INTO THE LIGHT

Children of Men ends with Theo — a character no longer willing to confront reality — helping the impossibly pregnant woman, Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey), give birth. Warring soldiers and refugees part like the Red Sea for this miraculous sight, a baby in their midst, an impossible glimmer of hope in the darkness. Theo and Kee then board a rowboat to meet a boat that may or may not carry them to salvation. Maybe there is no escaping this nightmare. Maybe it really is all over.

Then, out of the fog appears an actual light in the darkness, a buoy marker, pointing toward the unknown.

A moment later, a shadowy ship emerges, large and loud, bearing down on the rowboat like the future is bearing down on us.

There’s no way to know for sure if whats next will go Kee’s way — or humanity’s — but there’s a chance we’ll escape our arrested development. There’s something to cling to. There’s…hope.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

I’d not considered that the stagnation of cinema might be the result of a refusal to confront reality but it’s an interesting theory. I agree that the majority of film releases in recent years have felt pretty stale. I think it is ironic that this idea of a comfort blanket is resulting in lacklustre entertainment which is anything but comforting. In fact, when reading this, I was most reminded of the use of soma in Brave New World to sedate the masses. Dystopia is surely here!

I enjoyed this essay, especially when read alongside last week’s. Thank you.

Another great article. I’ve not read Station Eleven or seen Children of Men, but they’re on my list now. I would put your book, Psalms for the End of the World, in this category, as well. Sometimes, I just want to read or watch movies/TV for enjoyment or entertainment. But the ones that stick with me or change me are the ones where I feel uncomfortable or require me to think and challenge long held ideas.