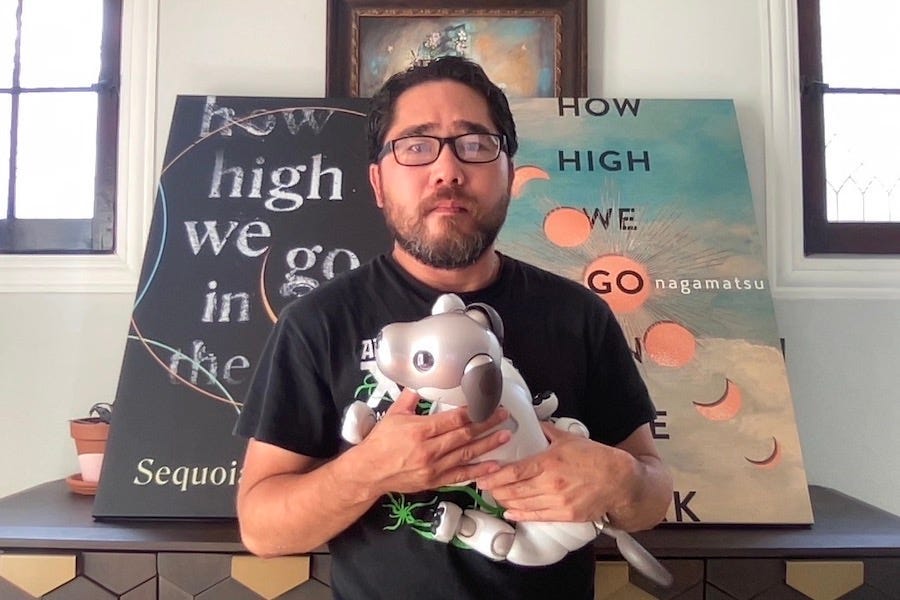

Q&A: Sequoia Nagamatsu on His Critically Acclaimed Novel 'How High We Go in the Dark'

We talk pandemics, climate change, and grief in fiction and real life…but most of all, about finding hope in both

The mummified remains of an early human child are discovered when global warming releases it from its permafrost tomb…a pathogen lying in wait inside the mummy’s brain is released…an Arctic Plague quickly spreads, mutating human organs, producing strange glowing constellations under our skin, and killing tens of millions.

This is the set-up to Sequoia Nagamatsu’s debut novel HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK, which was penned before a real-world pandemic blew up the early twentieth-first century. The book is a meditation on grief, collective trauma, our species’ misplaced priorities, and, most of all, the sustaining and ultimately transformative power of hope when despair and surrender make more sense.

HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK landed in my lap, as it did for many readers, at the height of COVID and provided me a cathartic experience I desperately needed. More, it was just a stunning piece of speculative fiction, superbly crafted and written. This is why I quickly reached out to Sequoia when I started this artist interview series and screeched (more or less), “Sequoia said he was down, Sequoia said he was down!” to my wife when I got his message that he was willing to let me interrogate him. Our conversation revealed just how much of himself he had poured into HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK, the unique challenges he faced editing a novel post-COVID about a fictional pandemic conceived and written pre-COVID, and how the book’s journey has changed him.

COLE HADDON: You wrote HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK, a novel predicated on the arrival of a lethal global pandemic, before COVID-19, but you sold it to HarperCollins three months after COVID was first announced. It feels like a daring decision, taking a pandemic-centric manuscript like yours out to publishers during an actual pandemic. Tell me what that was like for you.

SEQUOIA NAGAMATSU: I had been working on the manuscript for a long time, and, when my agent approached me about going on submission in Spring 2020, we had a very different conversation than the one I had dreamed about. We deliberated about if we should delay submission until the pandemic passed, but neither of us knew when that might be — or if we might risk the possibility of another writer swooping in with something similar in the meantime. Ultimately, we decided to push forward carefully and strategically, knowing some editors would be automatically wary of taking on a book with any kind of plague element.

CH: And what was that approach?

SN: I wrote a personal letter that accompanied the manuscript, highlighting that HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK was indeed closer to a book like Emily St. John Mandel’s STATION ELEVEN than, say, a more sensational depiction of a pandemic. In other words, a book about smaller moments, humanity, community, but one that was nonetheless using the speculative as a lens. And I think it was the reaction to STATION ELEVEN in the early days of lockdown that also eased early fears. People react to trauma in different ways, but many do lean into a moment, reading books and watching films in order to better articulate or understand what they’re going through. Some might even find catharsis from reading about a situation far worse than reality.

“I think on some level writers want their work to matter on some deeper level. It’s just not often that we are able to see it happen in real time.”

CH: I’m curious what it was like for you during those early months of COVID. I imagine you had to juggle flying high from selling your first novel — a kind of dizzy feeling that usually takes a couple weeks to even fade — with the fear all your hard work might not be marketable in a world where maybe nobody wanted to read about living through a pandemic while actually living through a pandemic?

SN: While I was certainly flying from the sale, I had spent weeks, if not months, already anxious about the reception of the book. That anxiety wasn’t really dispelled until after I started seeing reactions of the novel from people who weren’t professionally involved with it or who might potentially become involved — for example, film folk. It was really everyday ARC readers from the general reading public with kind words that kept me going long before professional reviews rolled in. People said they had cried, but felt uplifted. People who had suffered losses from COVID saw it as a deeply important book that got them through their grief.

CH: How did that feel, being told that about your work?

SN: It’s hard to put into words, honestly. I’ve never been the kind of person who knew how to take praise or kind words well. I was always the take the trophy and run away from the crowds and awkwardness sort of kid. But I suppose it felt assuring that my work wasn’t just a story I wrote, some beautiful dream strung together with considered sentences. I think on some level writers want their work to matter on some deeper level. It’s just not often that we are able to see it happen in real time, that we’re told that something we wrote dug someone out of a hole or even saved them in some way.

CH: There are always changes after a publisher picks up your book. But were there any aspects of HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK that you specifically reworked in the wake of COVID’s arrival?

SN: Let me tell you that I was desperately awaiting those edits because I needed structure in my life, something to do while I was trapped in my house even if that meant leaning into some very difficult subject matter. But as I waited, and as I saw COVID unfold, I needed to think about what I had predicted by coincidence, what I wanted to diminish in the final draft, and how I wanted to represent Asian and Asian-Americans when violent attacks against the Asian community were escalating, stirred by both COVID and Trump’s problematic rhetoric. Of course, the Arctic Plague in my novel was far more severe and otherworldly in many ways, but I didn’t want readers to relive COVID. I wanted them to live in a world I created. Any reference to social distancing and masking was downplayed or taken out in the final draft. I emphasized the cosmic origins of the plague, some of the symptoms that would never, I hope, occur in our reality — the shapeshifting nature of organs, stars dancing under the surface of our translucent skin.

CH: A stunningly beautiful detail, easily one of my favorites in the book.

SN: I also ensured that my Asian characters were never ever othered or exotified in any way. The immigrant story is not my own. The war story is not my own. Growing up, I long desired the kinds of Asian stories we’re just now seeing more of in Hollywood…the second, third generation Asian-American who might have a very tenuous connection to their heritage, but nonetheless juggles multiple identities. I wanted to showcase a diversity of the Asian experience as my characters simply tried to survive and find solace like anyone else. Perhaps above all, in the dark time we were living through, I tried to inject hope in even the most tragic of chapters, making sure that hope compounded. I did this just as much for my characters as I did it for myself.

“In the dark time we were living through, I tried to inject hope in even the most tragic of chapters, making sure that hope compounded.”

CH: I’ll come back to HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK in a moment, but this seems like a good place to ask about who you are beyond your writing. I sense from the novel, what I’ve gleaned about you from Twitter, and that last answer of yours, your identity is far from as simple as “I’m from California.”

SN: Well, I was born in Southern California and in the first couple of years of my life I moved around a lot with my father who had gotten divorced. I called New Jersey, Maryland, and New Hampshire home before ultimately landing in Hawaii where I was raised by my grandparents until I was twelve. As an only child I was always bookish and somewhat weird by nature. I was deeply fascinated by space and space exploration early on and devoured all things STAR TREK.

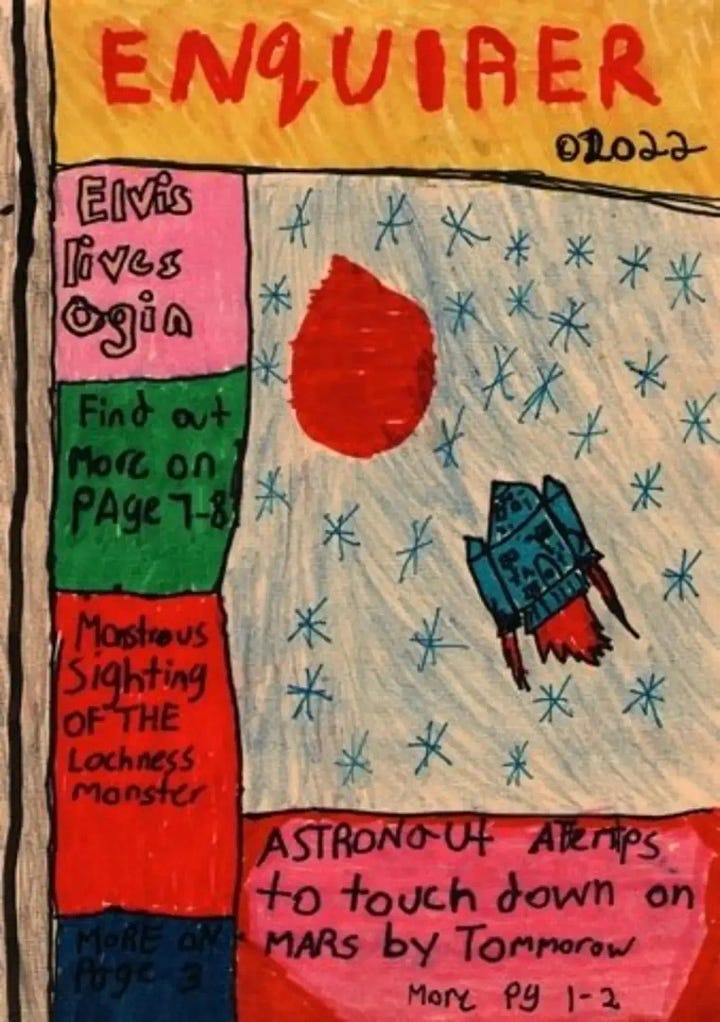

SN (cont’d): This fandom coupled with an early interest in folklore and mythology — probably due in part to Hawaiian elementary education really stressing Hawaiian myths and heritage — planted the seeds of later writerly obsessions. But I did start writing back then as well, mostly handmade tabloids, mimicking the stacks of the NATIONAL ENQUIRER that my grandmother read.

SN (cont’d): I moved to the San Francisco Bay Area for middle school and high school — a middle-class kid who somehow found himself surrounded by the uber-wealthy in Palo Alto and Los Altos. I excelled as a student for the most part, but I also found these years somewhat isolating, and I think class differences played a part here.

CH: When did you escape Silicon Valley?

SN: For college in Iowa [Grinnell College], where a passion for environmental conservation was ignited — often at the expense of class work. Chained myself to things. Played hippie in forest with anarchists. I was even co-managing the student-run arm of the Sierra Club forest campaign on a national level for a while. I switched majors a couple of times and ultimately landed on anthropology, but graduated feeling somewhat aimless and maybe regretting that I hadn’t pursued writing more. And I had become disenchanted with some of the environmental organizations I had been involved with, seeing that bureaucracy and hypocrisy exists everywhere.

“Something I realized pretty early on as a young activist is that some people well never be convinced by a protest… These tactics have their place. But art is another tactic.”

CH: This is all fascinating stuff I had no idea about. I have to say, I admire how well you translated your personal activism into fiction in HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK. The restraint you demonstrated, given your commitment, is extraordinary, but that’s also probably why the climate despair that permeates many parts of the book is so effective.

SN: Maybe one day I’ll write a more activist forward climate fiction book, but HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK was first and foremost fueled by my desire to explore grief and human connection. There are, of course, climate change considerations as well, but perhaps that’s the point? How can we take care of the planet if we can’t even care for ourselves on a fundamental level? When we can’t find empathy for other communities let alone our own. And something I realized pretty early on as a young activist is that some people well never be convinced by a protest, by someone waving a clipboard or a banner in front of their face. These tactics have their place. But art is another tactic. And art can sometimes bleed through the cracks of politics and skepticism.

CH: I couldn’t agree more. For me, art is, by its very nature, political. What happened after you graduated from Grinnell?

SN: Almost immediately, I returned to the SF Bay Area, because why not live in one of the most expensive places in the world when you’re aimless?

CH: Makes sense to me.

SN: I started and got involved in several writing groups. Some met in bars and some met in coffee houses. Some imploded due to social drama. Thanks in part to my environmental activist background, I found periodic employment as a large-scale event planner — street festivals, arts festivals, galas etc. But I was fundamentally unhappy. The hustle of work sometimes left little time to write, and I was constantly broke. This coupled with personal dramas with social circles led me to teach English in Japan for a couple of years.

CH: More and more of HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK is making sense to me as you talk. [Several chapters of Sequoia’s novel take place in Japan].

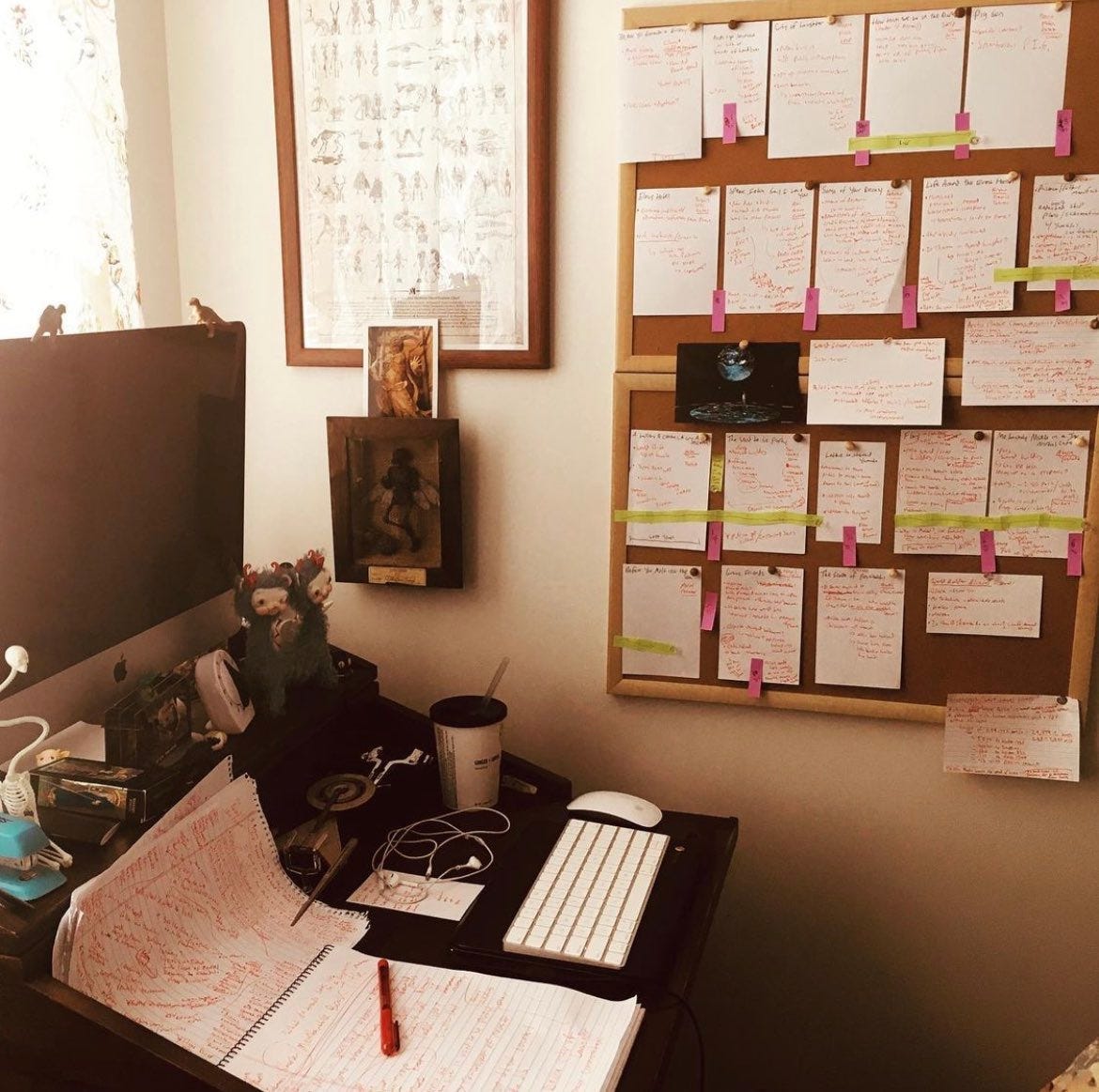

SN: I think it was really there — where I was both exploring my own heritage but also culturally and linguistically isolated — that the writing began in earnest. When I got home, I wrote and read for hours. Some of my early writing efforts were noticed by other writers, and I got involved in an international anthology project with authors far older and far more experienced than me. From there, I think a more predictable path for a — still very lucky — writer followed. I applied to and was accepted to an MFA program, I landed teaching gigs and eventually got tenure, and I began carving out a routine juggling the life of an academic and the life of a professional writer.

CH: Going back to your environmental activism for a moment, to your eventual despair with some of the organizations you worked with. When you brought this up, I immediately thought of the character of Clara in HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK. Her despair echoes what you just described. I didn’t name my own novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD (2022) because I believe our age defined by optimism, but through writing it, in touching that despair, I hoped to find my own catharsis. Before COVID ever entered the picture, what was it that compelled you to start writing HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK?

“I borderline became obsessed with how we end and how there must be a more humane way to conceive of death.”

SN: I think it was a recognition that our society doesn’t really allow for people to come together, grieve, or reflect in the ways we need to when it comes to self-care, community, and the overall betterment of our society. Global culture and almost every industry — including academia and healthcare — has proclaimed that we must be in a constant state of busyness. Time is money. And apparently care — actual care — is worthless. I saw this with my own grief, with how quickly people are forgotten, and how impersonal the business of dying can be long before COVID made it impossible to sit by the bedside of loved ones in 2020.

Back in my college days, I remember reading a book called THE AMERICAN WAY OF DEATH by Jessica Mitford, which explored the business of the funerary industries, and I suppose this book stuck with me. I’d later read books like Mary Roach’s STIFF: THE CURIOUS LIVES OF HUMAN CADAVERS, Sherwin Nuland’s HOW WE DIE and HOW WE LIVE…even a book that married quantum physics and the afterlife. I borderline became obsessed with how we end and how there must be a more humane way to conceive of death. I went to funerary expos, I researched start-ups that would do non-traditional things like turn cremated remains into boxes of pencils. But I think through all of that research, I ultimately realized that the main obstacle to a more humane death — and life — is ultimately the speed in which we have forced ourselves to live. A pandemic like the one in my novel gave people a liminal space to think about what really mattered.

CH: Art has a strange, malleable quality because its relevance, even its meaning can be transformed by history. It evolves, sometimes decade by decade. In HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK’s case, it’s hard to argue with the idea that it was, by horrific happenstance, imbued with additional significance by COVID. Can you talk to me about how your own relationship to your novel has changed because of COVID?

SN: [It’s] changed a great deal from being fearful of how the book might be received, to being very defensive of the book being labelled “pandemic fiction”, to being welcoming of HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK being part of emerging/evolving conversations about the COVID era — and climate change. My book is populated, much like our own world, with highly imperfect and dysfunctional people, people who fail to make the right decisions, people who don’t know how to love or connect. But ultimately, at least in my novel, people came together. Empathy and community helped heal the world. It’s a nice idea, and one that’s still a reach, but I think it’s a worthy dream to discuss and forward in art.

SN (cont’d): On a more personal note, I think writing this book and having an evolved understanding of the book I wrote helped me better appreciate the people in my life. I lost both my father and grandmother during the last couple of years — and not unlike some of the characters in HOW HIGH, I was also estranged from them. I was revising a chapter of a character who couldn’t make the right decision in time when I found out my father was dying from cancer. Entering a dialogue with that character helped me muster the courage to speak to my father one last time even if we didn’t have the conversation that we probably needed to have. At least I got to say goodbye. As I’ve already noted, I think a lot of my readers have similar experiences…some have said that reading the book made them want to hug their child, others said they called their parents. I even reached out to old friends I hadn’t talked to in years.

CH: I had a similar experience myself, in fact, except in my case my father had died a year before your novel landed in my lap. HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK resurrected and amplified the sense that an opportunity had been missed, to fix something that was broken. There were many moments of vicarious conversation with my own grief in its pages. It’s a complicated thing for any writer to pull off, to create moments so specific that they ring true while simultaneously leaving enough of a space for the reader to inject themselves and find their own truths in the experiences they’re reading about.

SN: I think no matter what a writers says in interviews, a part of them will always be there in the work — a character, a slice of several characters, a house, an object. We can’t completely divorce ourselves from how we view the world and how we view the world is deeply influenced by things like personal losses, friendships, love, etcetera. I’m aware of this lens when I write. I sometimes can see this in books and film — the preoccupations that drive the art. But I always try to make sure what I produce is ultimately fiction. Something is different or many somethings. I don’t want my readers to be given a memoir or something that resembles nonfiction, or else I’d just write a different kind of book. The beauty of fiction is leaving that negative space — a possibility space — for the reader to interact with on their own terms.

“In some ways, I think the days of waking up and writing with no expectation are gone.”

CH: To wrap up, you talked about how HOW HIGH WE GO IN THE DARK taught you to appreciate the people in your life more. But I wonder, did it teach you anything as a writer?

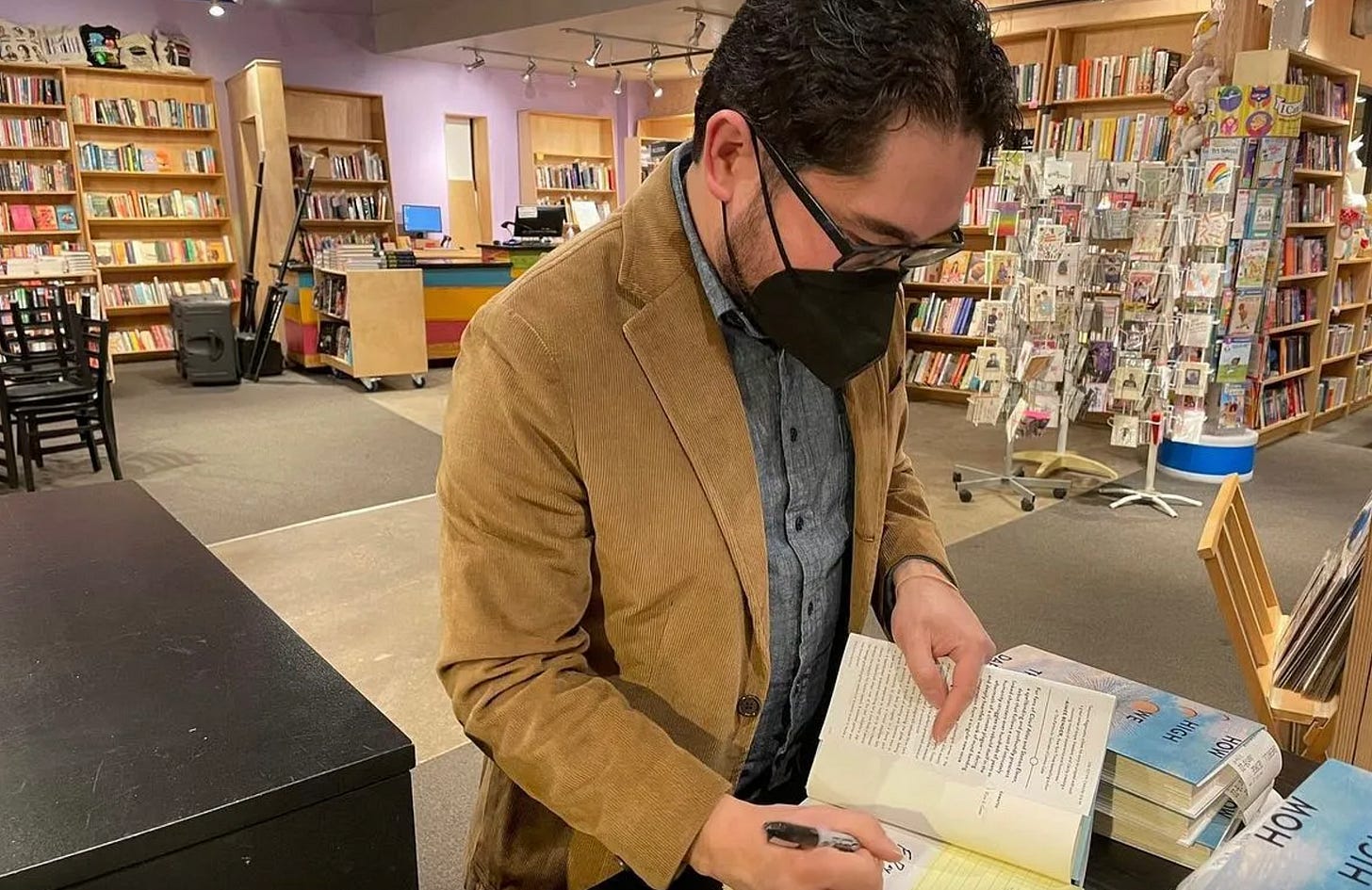

SN: I think I learned a lot about myself as a writer, but also as a writer who is published by a major publisher, which is kind of a different skillset and world in a lot of ways. Before this book I largely worked on my own. Maybe I gave a draft to a writing group or my partner or a friend, but the process was one that I mostly controlled. But when you’re publishing with HarperCollins at the heels of a major book deal, and you’re being told in more ways than one that your publisher is going to really support your book, you have to learn to collaborate on a higher level, to become both a private writer and someone who can, at least in brief spurts, become the public face of something that was really a team effort of probably a dozen or more people.

In some ways, I think the days of waking up and writing with no expectation are gone. And there’s a beauty in that kind of creation, a purity. But I’ve realized that I can churn out work when I really need to. I’ve slowly learned to say no to things that will take me too far away from the core of who I am as a writer. I need to protect my time. And I think most of all, I’ve learned that it’s okay to invite other voices in my head without feeling like a sell-out — potential audiences, potential reactions, even the ways my book might be positioned in the marketplace (none of these things are bad) — and, of course, I want my books to sell well, to find people. But at the end of the day, this quorum of voices need to agree with the hearts of the characters I’ve created. I don’t think that will ever change. And if it does? If my characters follow those voices completely without following their own? Well, perhaps then I would have lost my way. I hope I never get there.

You can read more about Sequoia Nagamatsu and his work at his website or find him on Twitter.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world: