'The Fabelmans' Is Much More Than Steven Spielberg’s 'Most Personal Film'

On the film's first anniversary, let's examine the deeper conversation the director is having with cinema, artistic expression, and even his own oeuvre

Noun

fable (plural fables)

A fictitious narrative intended to enforce some useful truth or precept, usually with animals, etc. as characters; an apologue. Prototypically, AESOP’S FABLES. Synonym: morality play

Any story told to excite wonder; common talk; the them of talk. Synonym: legend

Fiction; untruth; falsehood.

THE FABELMANS, a semi-autobiographical dramatization of Steven Spielberg’s childhood and coming-of-age as an artist, was billed as the director’s “most personal film to date” when it was released in November of 2022. There’s much marketing savvy involved in labelling it as such, as Spielberg himself — how he became the director who shaped our collective imaginations more than any other director in the past fifty years — is far more appealing to contemporary audiences, I imagine, than a film about a kid from a dysfunctional family who discovers an emotional escape through making motion pictures. But by focusing on the real-world story behind THE FABELMANS — what’s true and what isn’t — we risk missing how deftly Spielberg is using the medium he was a master of before he was even thirty years old to meditate on the tension between reality and fiction that has defined his creative life and, in fact, the history of cinema itself.

As part of the promotion of THE FABLEMANS, Steven Spielberg discussed on NPR’s FRESH AIR how he grew up in what I would describe, from his sympathetic explication of it, as a house of lies.

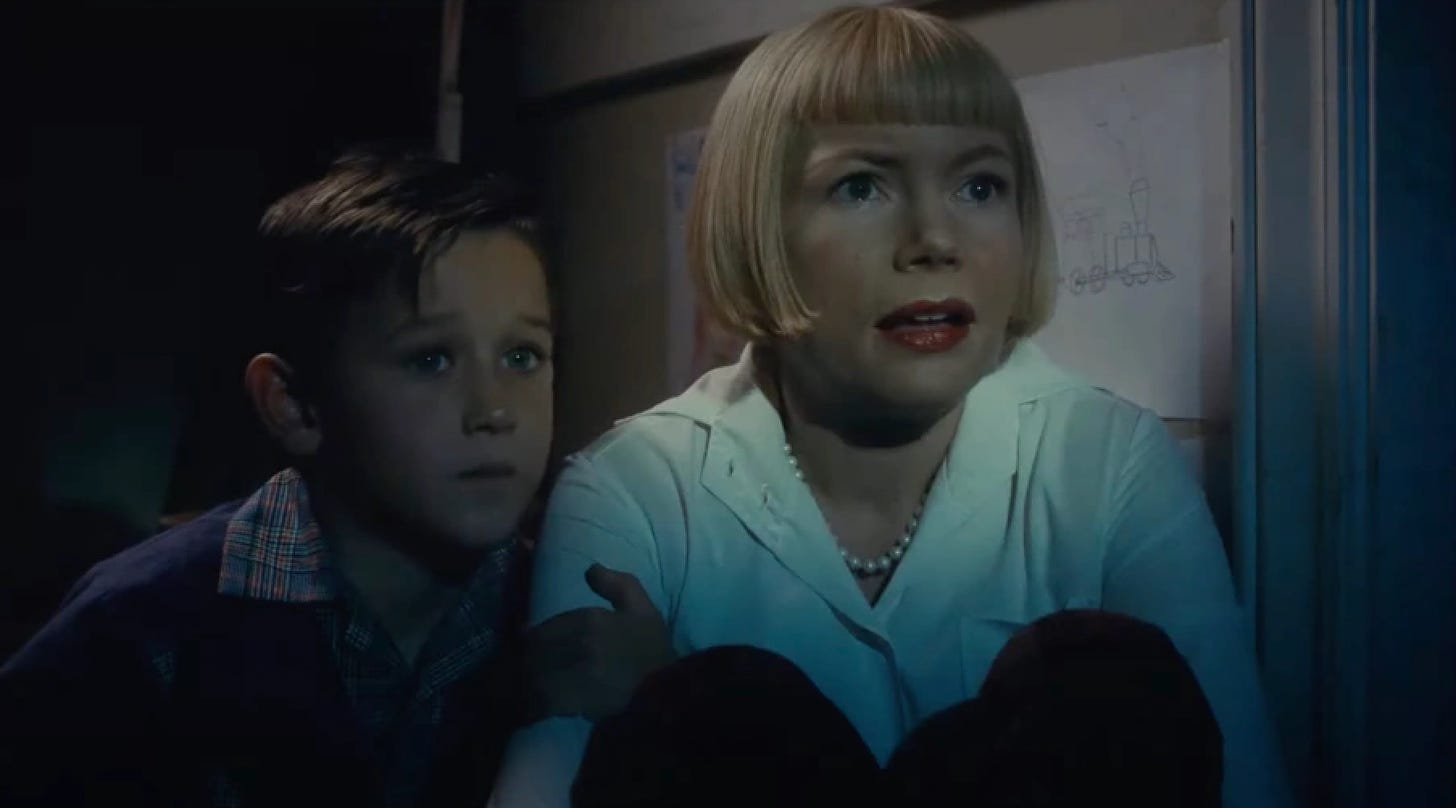

Most of this shows up in THE FABELMANS itself and is periodically described as chaos or chaotic in some form or another. This emotional bedlam lives at the heart of Spielberg’s cinematic alter-ego, Sammy Fabelman; the kid is both terrified of it and naively desperate to control it any way he can. His mother Mitzi, played brilliantly by Michelle Williams, recognizes his anxiety when she and her husband Burt (Paul Dano) discuss why a six-year-old Sammy is repeatedly crashing his Lionel model train set, recreating a violent train crash he witnessed in THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH and is now obsessing over.

After this scene, Mitzi tells Sammy they’ll secretly use the family’s 8mm camera to film the train crash so Sammy can watch it over and over “till it’s not so scary anymore.” This is the film’s inciting incident, as I would define it. This is the moment everything changes for Sammy and, we presume, Spielberg because he discovers the power of the moving image to control whatever he is frightened of — whether that’s train crashes or, later, his parents’ divorce (there’s an especially affecting scene where Sammy imagines himself filming this scene, trying to assign order to the chaos around him).

This seems to have been the case throughout Spielberg’s life, by the way. In Susan Lacy's 2017 documentary SPIELBERG, he observed, "I've avoided therapy because movies are my therapy."

Now, I want to draw attention to two key scenes in THE FABELMANS and the conversation they are having with each other in the film, but also the conversation Spielberg is having with himself, his art, and this — “his most personal film”. The juxtaposition of these scenes, or rather how film itself is used in them, dramatize the aforementioned tension between reality and fiction and help audiences, ultimately, understand how art is produced from it.

Another way to say that is: Spielberg uses these two scenes to provide a MasterClass on what cinema is.

The first scene is a significant turning point — or reversal — in the Fabelman household and this film and is one of the many that remind us that, as easy as it is to view THE FABLEMANS as autobiographical — “it’s Spielberg’s most personal film, like, ever, guys!” — it’s only semi-autobiographical. The reason I say this is that Steven Spielberg and his co-writer Tony Kushner have created moments in which cause and thematic effect are neatly explained for dramatic effect, justifying Sammy’s character transformation, rather than doled out as messy and ugly as they are when screenwriters aren’t at work. In other words, thematic relevancy manifests where real life, full of the chaos Sammy fears, naturally resists. THE FABELMANS is a film, and Spielberg is very conscious of that, right down to a very meta-gag I’ll get to later on when I discuss a climactic argument with a bully.

The narrative turning point/reversal in question comes after Sammy (at this point played by Gabriel LaBelle) has been reluctantly charged by his father to create a film out of all the footage he shot of the family’s recent camping trip. This is because Mitzi is mourning the death of her mother, and Burt needs Sammy to cheer her up.

As Sammy edits this vacation film together, he begins to notice something we, the audience, have already come to suspect — Mitzi and “Uncle” Benny (Seth Rogan), Burt’s best friend and co-worker, not to mention the only non-family member on this camping trip, are engaged in some sort of romantic affair.

This fact, which Sammy has missed despite it being right in front of his eyes the whole time, is slowly revealed to him, one frame at a time, on his editing table. Film, once a sanctuary for him, a place where he is a god capable of exorcizing chaos out of his reality, is suddenly corrupted. He stumbles backwards…frightened by both what he’s witnessed and the potentially malevolent power of his 8mm camera.

Later, when Mitzi reaches her breaking point at how Sammy has emotionally cut her off and strikes him, he directs her to sit in his closet where he watches all the films he shoots (a closet reminiscent of the one in E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL). He mounts on his projector a reel he has cobbled together from the scraps he edited out of the “happy lie” he and Burt previously showed her to cheer her up, and closes the closet door behind him. Mitzi is left alone, presuming she’s about to experience another of her son’s wonderful cinematic creations. Instead, she, like Sammy, discovers the power of the moving image to present brutal reality. The camera sees what we don’t, and can reveal what are too afraid to see. In this case, no manipulation of events is necessary on Sammy’s part — because this isn’t cinema.

Reality is horrifying all by itself.

By the way, Williams delivers a powerhouse performance in this sequence. We never see the film being projected on the wall, only her reaction to it. It’s a dark interpretation of the “magic of going to the movies” scene typically presented in these kinds of love letters to film — as an almost supernatural event (think CINEMA PARADISO, more recently in BABYLON, and, oh yeah, earlier in this very film).

Near the end of THE FABELMANS, another of Sammy’s early films, SENIOR SNEAK DAY, is screened. This is the other key scene I want to discuss. As I do, consider how it contrasts with the last one I walked us through.

SENIOR SKIP DAY is a fun documentary-style film about Sammy’s high school senior skip day beach party and it stars his entire class. In fact, his schoolmates comprise his audiences this time around, including kids who have violently bullied him and attacked him with anti-Semitic insults.

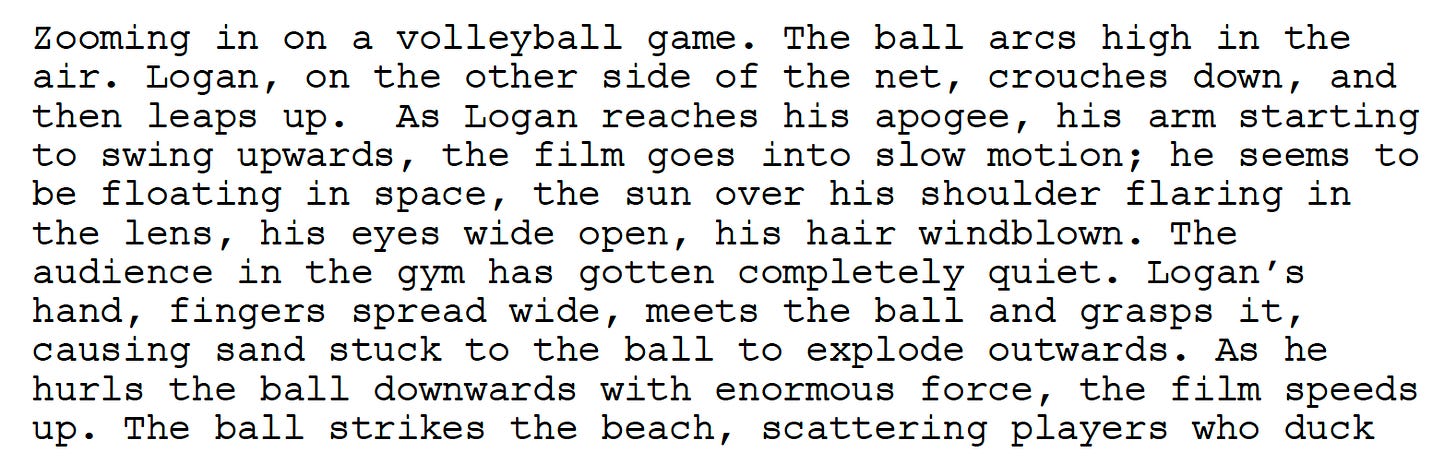

But in the film, the bully Logan (Sam Rechner) is not the villain as you — or he, as it turns out — might have expected. Here’s how Steven Spielberg and Tony Kushner’s script describes the point where the film-within-a-film takes a surprising turn.

Slow motion. Float. Shoulder flaring in the lens. Hair windblown.

This cinematic adulation of Logan’s body and general super-humanness — the elevation of Logan to a kind of Aryan image Leni Riefenstahl would’ve salivated over with her camera — continues until the film wraps and the lights come back on. Everyone in attendance is awed by Logan as a result, cheering him on as if he’s King Shit McShitty the First. His friends even try to lift him up like a golden calf, but he refuses, angry, embarrassed we’re about to realize, and stalks out.

This is very different than what happened in reality, and is yet another reminder we are not watching a true biography concerned with veracity. Joseph McBridge, one of Spielberg’s biographers, explained in a SLATE article:

…as Spielberg once recalled, his tormentor, after seeing Senior Sneak Day, “came over a changed person. He said the movie had made him laugh and that he wished he’d gotten to know me better.”

McBridge is quick to make the point:

Altering reality to heighten one’s life story, explore deeper truths, and make it come out the way one wishes it might have happened are among the purposes of autobiographical dramatization.

In THE FABELMANS, Spielberg is, as I’ve mentioned, entirely conscious of this bastardization of reality to find something true. In one of several self-referential gags in the film — including jokes about his underrepresentation of women in his work or fear of “boobies”/women’s bodies) — Logan eventually makes a crack about what McBride is describing here.

This crack shows up in the scene that immediately follows the screening of SENIOR SNEAK DAY. Logan finds Sammy alone in a school hallway, face in his hands, and confronts him about what everyone just watched.

Sammy struggles to answer why, at first saying he just pointed his camera and “it saw what it saw”. But this is, as Logan says, bullshit even if Logan doesn’t fully understand why yet. Sammy didn’t just point at a camera, after all. Unlike the reel of film he screened for his mother, this skip day film is an assembly of images and sequences, even early movie tricks that qualify as special effects, in which each moment contributes to a larger and cohesive narrative. He’s even juxtaposing shots; not with Sergei Eisenstein’s sophistication, but he’s intuitively doing so for emotional effect.

Basically, Sammy has taken facts, as the camera filmed them, and manipulated them to tell a story of his own making. In doing so, he has, consciously or unconsciously, taken reality and turned it into fiction to reveal a truth about Logan that Logan is terrified by.

This, unlike the camping film that Sammy screen for his mother, is art with a capital A.

More, Spielberg has taken whatever happened to him during the real-life screening of this film, manipulated it with Kushner’s assistance — doing the same thing Sammy does in the film — to have an even deeper, bolder metatextual conversation with audiences about cinema’s unique power and why he felt compelled to dedicate his life to telling stories with it.

At the conclusion of THE FABELMANS, the legendary John Ford (hilariously played in a bit part by writer-director David Lynch) snarls at Sammy, “What do you know about art?” For Ford, it’s a sincere question intended to intimidate the kid. But it’s an ironic question from Steven Spielberg and Tony Kushner’s role as storytellers here, meant to hammer home the film’s theme because Sammy already knows what art is.

While THE FABELMANS might be a family drama and even be a way for Spielberg to forgive his parents for the pain they caused him, the cinematic point of the film, the film’s greatest accomplishment, I would argue, is a kid discovering that art is the manipulation of any medium to tell a story in an effort to produce truth where, if you’re especially talented, none previously existed.

This is driven home, playfully, maybe even mischievously, in THE FABELMAN’s final shot. Ford has loudly instructed Sammy that a horizon at the top or bottom of an image is interesting - but in the middle, it is not. As Sammy leaves Ford’s office, buoyant from meeting his idol, he strides toward his future and a horizon positioned at the center of the frame — until, without a cut, Spielberg, the god behind THE FABELMANS, manipulates the image to drop the horizon to the bottom of the frame where it will be “more interesting”. Reality turned into a fiction to reveal a truth, with the added fun of Spielberg pulling the curtain back on himself to reveal — with one hell of a wink — the Wizard of Hollywood at work.

You can read THE FABELMANS script, written by Steven Spielberg and Tony Kushner, here.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

If movies are his therapy, we have all benefitted from his misplaced neuroses.

Really enjoy these essays and your ability to expose the hidden parts to view and discussion. Thanks for sharing.