The Real Reason Why 'Watchmen' Is So F@cking Great

Or: What Alan Moore's use of ambiguity in his seminal comic book series can teach you about storytelling (and humanity)

Rorschach test

Noun

ˈrɔːr.ʃɑːk ˌtest

(also inkblot test)

a psychological test in which a person is shown spots of ink and asked what they look like, as a way of learning about the person’s personality or feelings

“There are always two people in every picture: the photographer and the viewer.” – Ansel Adams

As a general rule, ambiguity scares the shit out of human beings. We look for concrete explanations of why something works, especially about “big subjects”, and tend to reject any that require nuance of any kind. If you’re confused by what this means, consider how “faith” – the unquestioning belief in unprovable “truths” – so easily trumps observable evidence that requires more than a sentence to explain and understand. Faith, in my experience, is not an act of submission to the divine, but rather a rejection of any subject too big to understand in the average time it takes to read a 140-character tweet (or whatever Elon Musk is now calling them). To be fair, this isn’t a terrible way to survive reality, at least on an individual level. Reality is scary AF, as I mentioned, and dealing with it is emotionally exhausting at the best of times and spiritually crippling at the worst. Sky deities offer a convenient way out of all that hard work - similar to superheroes, a point that will become relevant later on. This is all my longwinded way of saying: if you present your audience with narrative ambiguities that make them responsible for defining your story’s moral and/or ethical meaning rather than you, then you should be prepared for them to tell you something pretty awful things about themselves. Just ask Alan Moore, the writer/co-creator of the greatest comic book series ever published - and, by many metrics, one of the greatest books of any kind ever published.

Now, let’s take a look at what we can learn about storytelling from Moore’s use of ambiguity in Watchmen…

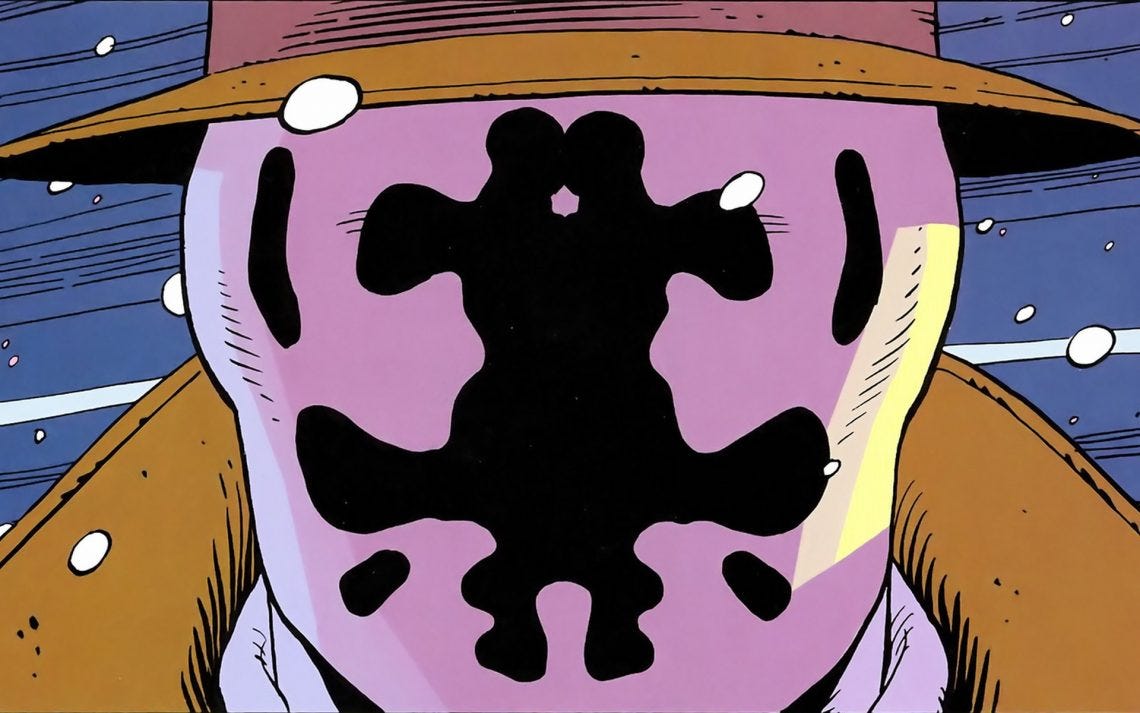

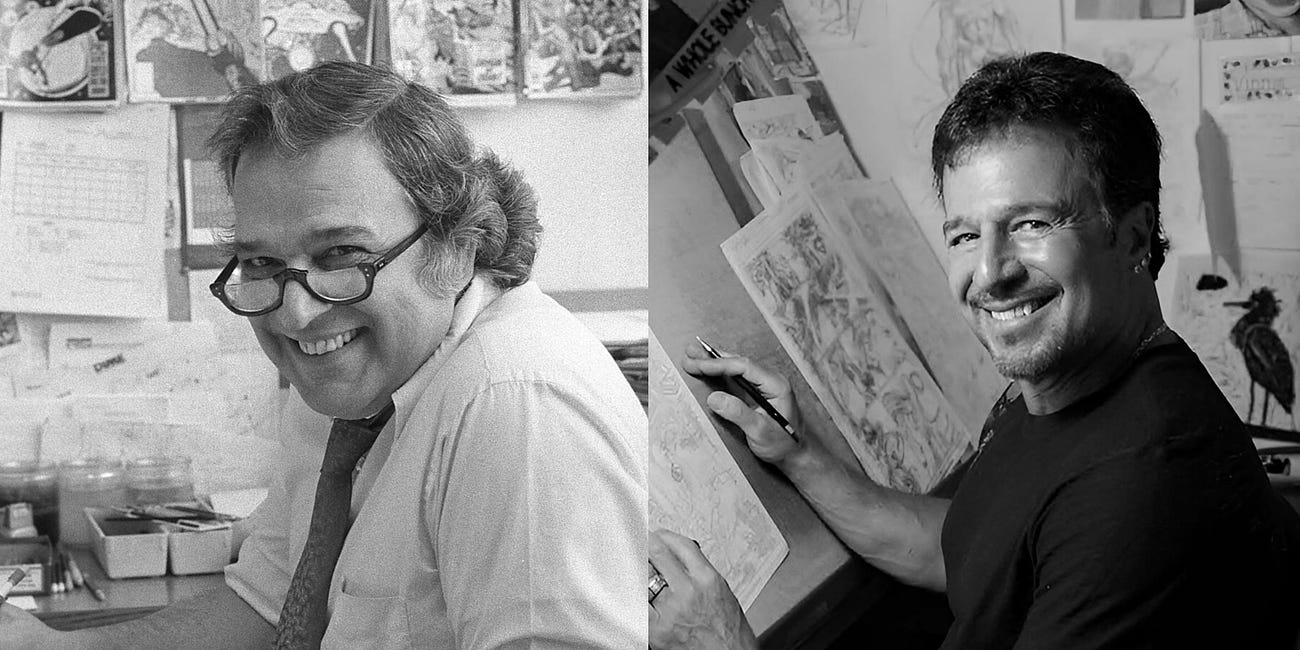

In 1986, DC Comics launched Watchmen, a 12-part limited series written by Alan Moore and spectacularly illustrated by Dave Gibbons (seriously, it’s one of the most cinematic reads in comic book history). It’s set in an alternative history in which the coming of a god-like super-being named Doctor Manhattan led to the United States winning the Vietnam War. As a result, Richard Nixon was never scandalized by Watergate and has since been elected to several more terms. By the time the story kicks off in ’85, America has become a quietly totalitarian state with Faux-Superman as its chief protector against the dastardly Soviet Union. The costumed adventurers (superheroes) that used to patrol its streets, allies of Manhattan’s, are now outlawed…except somebody is knocking them off. A violent vigilante by the name of Rorschach determines to find out who the murderer is before his former compatriots all die. By the way, Rorschach wears a mask covered in ink blots that appear to move. This will become important as we discuss Moore’s intentions when he created this sociopathic character as his stand-in for the fascistic qualities of superheroes like Batman.

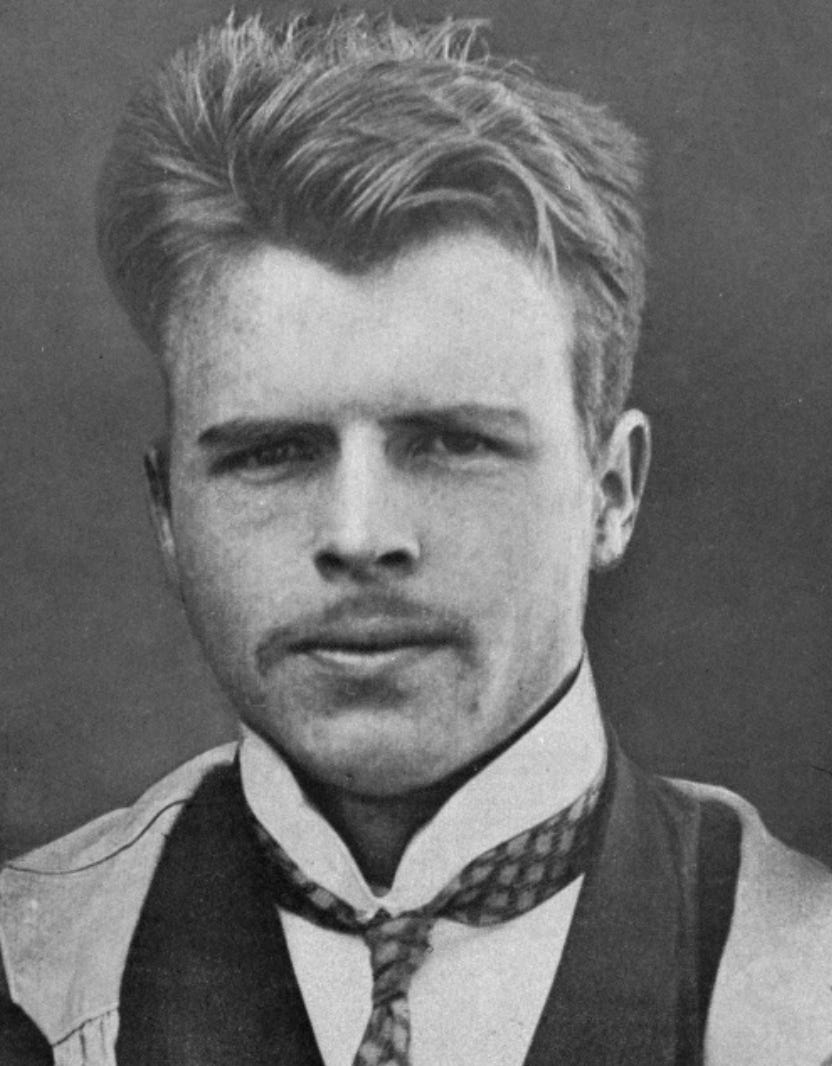

The ink-blot test, as we understand it today, was introduced in the book Psychodiagnostik (1921) by Swiss psychiatrist and all-around hottie Hermann Rorschach.

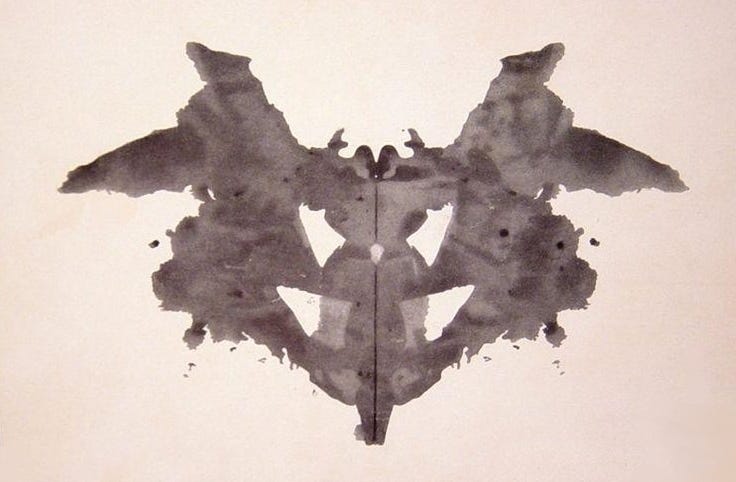

Hermann came up with the idea of using ten standardized “ink blot images” to reveal underlying thought disorders in patients. You’ve seen this in films and TV for years. It’s not a complicated idea at this point. A shrink in a suit shows you a card with a pattern of ink blots on it. You, probably in cuffs or similarly detained in an asylum where you’re otherwise convinced you don’t belong, then tell this shrink what you see in those ink blots.

For example: “Ooh, I see a beautiful butterfly fluttering through the field of flowers behind my childhood home.”

Or: “Oh lovely, I see my newborn son reaching up to hold my finger for the first time.”

Or maybe: “I see the same thing as you, Doc – a dog with its brains cleaved open. Wait, isn’t that what you see, too? I’m not crazy!”

The point is: what you see reveals things about you that you wouldn’t want to articulate, whether because you’re unaware of your disorder or because you’re very aware of the fact that you’re a serial killer who likes to eat cheerleader tartare.

Sixty-four years after Psychodiagnostic was published, Alan Moore created a series of superheroes intended to mirror and comment on the superheroes that had existed throughout DC and Marvel Comics by that point. By grounding these characters in the real world — or at least treating them as if they at least existed in a version of our world — the narrative is better able to explore our own culture’s toxic, perhaps juvenile relationship with masked vigilantes and their morally bifurcated existence. Nostalgia, as embodied by the comic book’s many flashbacks to the “golden age” of costumed adventurers, must give way to reality in Moore’s hands.

Put another way: a morally unambiguous black-and-white past, as simple and feel-good as any you find in holy books and implied by political slogans like “Make America Great Again”, is revealed to actually be a kind of social fascism when properly interrogated by a cranky, bearded comic book writer struggling to endure Margaret Thatcher’s United Kingdom.

The character of Rorschach embodies Alan Moore’s reconsideration of the popular obsession with superheroes. He lives by a strict code. Black and white, right and wrong, good and evil. “Whores” are no different than “kiddy rapists” in his mind - which is, I should point out, something my pastor told me during Catechism classes when I was only thirteen. The Lutheran God, the sky deity popular in my parents’ household, did not rank his commandments, or so I was repeatedly told. A sin was a sin, just another mark against you whether you cheated on your wife or murdered your neighbor for using his leaf blower at six in the morning — which is a pretty fucked up thing to tell a kid trying to develop his own moral compass.

This is how Rorschach moves through his world, unbending in his convictions and absolute in his righteousness, the perfect mouthpiece for Thatcherism and Reaganism. He’s everything that’s wrong with Batman and similar characters in Moore’s estimation - that is, if one properly interrogates Watchmen.

This might sound ironic to you when you consider there are legions of people who believe Rorschach is a hero to celebrate. These are the same people who have mistook the Punisher, a Marvel Comics character meant to comment on the fascism of American policing, for an idol. Just look at the cops across the United States who wear clothing depicting, get tattoos of, or cover their vehicles with the Punisher death’s head - a subject I’ve written about at length in “The Church of John Wayne’s Star-Spangled Wang”. Going back even further, one finds Dirty Harry Callahan is a first cousin to Rorschach.

But when it comes to the Punisher and Dirty Harry, it’s easier to understand how this confusion arose. Both are presented as heroes determined to do what’s right no matter what – avatars for American exceptionalism and the country’s role as the “world’s cop”. For those who embrace this kind of tyranny of the just, these guys superficially present as kindred spirits and make no invitations to deeper interrogation. The viewer must take that step themselves.

The difference when it comes to Rorschach is that Moore slapped an ink-blot test on the character’s face and named him after the test’s creator – the storytelling equivalent of shouting at his readers that it was up to them to interpret Rorschach’s actions, violent ideology, and dark morality for themselves.

Which is, of course, what a lot of people have done over the years.

Their reactions to this literary inkblot test have been…revealing, to say the least.

I used to wonder if Moore suspected how many people would embrace Rorschach as a good guy despite how often his writing implies profound trauma and mental illness, but it’s been a long time since I made that mistake. Moore has long understood how broken Western culture is and the violent hate that festers at the heart of it. I doubt he’s felt one moment of surprise at the West’s slide toward fascism since Watchmen was first published – especially America’s.

Before you keep reading, you should know, there be spoilers ahead, matey. I’m about to blow the ending of Watchmen for you. But also, I have to ask, what the fuck is wrong with you that you don’t already know the ending to the greatest comic book ever written?

Okay, es-tu prêt? Perfecto. Here goes.

The mystery at the heart of Watchmen is that one of the titular characters, the most intelligent man alive allegedly, has recognized that humanity cannot indefinitely survive under the benevolent thumb of good ole Doctor Manhattan. He hatched a plan to dispatch his fellow former costumed adventurers, drive Manhattan to abandon Earth for Mars, and force the United States and the Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war. The payoff is that he’s also genetically engineered a giant monster to be inter-dimensionally air-dropped into the center of Manhattan that will instantly wipe out millions of people before dropping dead. He is convinced the world will perceive this kaiju knock-off as part of a botched alien invasion and, desperate to protect themselves from more of the same, finally unite as one.

And you know what? It works, man. It fucking works.

Within minutes, calls for peace and unity break out. Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier announce they’re becoming life partners. Nuclear war is permanently averted.

I mean, sure, millions of people are dead and real estate in Manhattan just took a permanent nosedive. But also, the planet’s entire population was about to be annihilated in a nuclear holocaust, so maybe not all that bad if you’re into playing numbers like that.

Even Doctor Manhattan recognizes the brutal, horrifying genius of the plan.

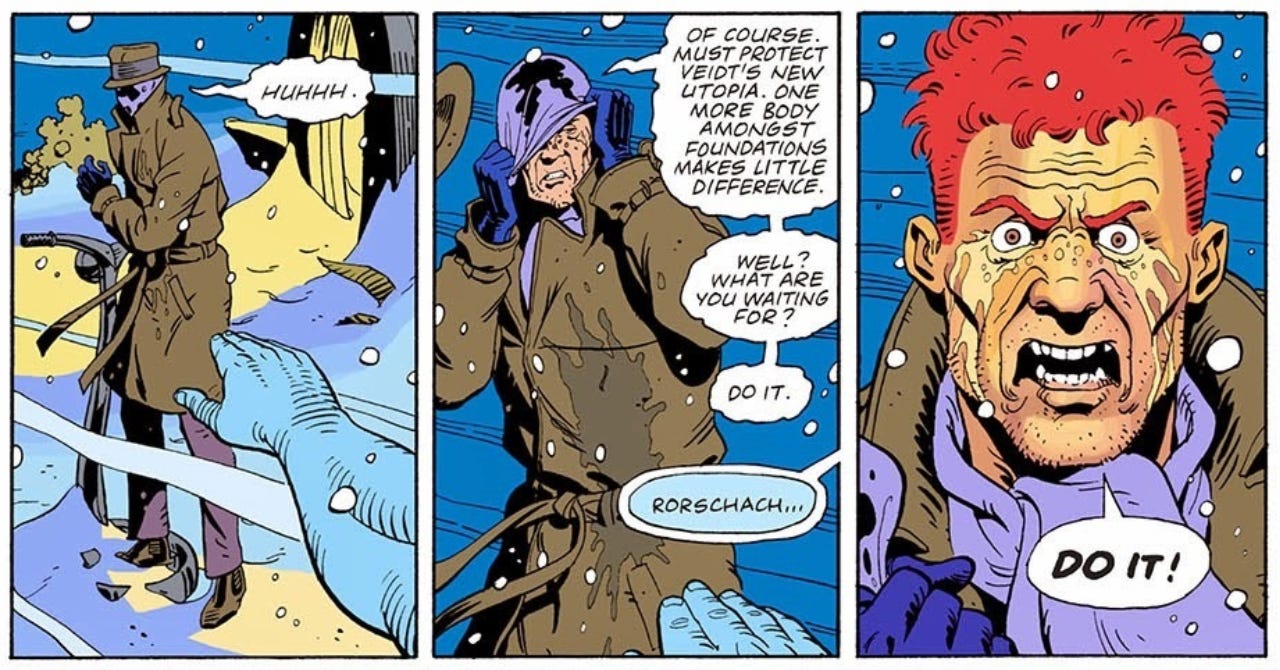

But Rorschach?

Not a chance.

Remember, this guy can’t bend in the slightest. The only gray he’s ever accepted is the color of a stormy sky, and even then he probably would only see it as shit-colored since the opposite of bright and sunny could only be blight and cancerous decay in his mind.

He refuses to remain silent, forcing Manhattan’s hand.

In the blink of an eye, Rorschach detonates into blood and gore. This image — this final literary Rorschach test — requires readers to tell the world what they make of the image.

As Ansel Adams once said, “There are always two people in every picture: the photographer and the viewer.”

Another way to put this is: you’re a part of Alan Moore’s story the moment you crack open his comic book and start reading, and by the end, it’s you who has to decide what it all means.

Ambiguity is the point of this article. Ambiguity and the role of your audience in the art you create. When you read Watchmen, you are not a passive participant. Whether you like it or not, you have to roll up your sleeves and get involved in the action and decisions being made on every page.

Sure, the superheroes you’re reading about are easy to cheer for. They kick a lot of ass, they like to bang while they do it, and they know how to drop one-liners like the best of them. But unlike the vast majority of comic books ever written, Watchmen wants you to realize how fucked up your reaction is to everything you’re reading. For example, isn’t it strange that Dan Dreiberg’s Nite Owl can only get it up when he’s breaking criminals’ bones? And isn’t it even stranger that you seem to be equally aroused by him destroying other human beings’ bodies? And isn’t even stranger still that you kind of got off a little when he and Silk Spectre translated all that violence into hot, sweaty sex and, in their frantic fornication, accidentally ejaculated a load of fire all over their city?

This is just one example of so many scenes that comic book readers of every religious background, political persuasion, and ethical disposition have when reading Watchmen. Nobody escapes unscathed.

Even when you get to Rorschach’s big, bloody finale — a moment that you can’t help but gasp in horror at while simultaneously thinking, “Well, that was pretty fucking cool” — you’re asked to decide if you agree the sociopathic Far Right loon who posted evidence of this grand conspiracy to a Far Right magazine before his death or the hyper-intelligent billionaire and god-like being who thought trading a few million New Yorkers’ lives for world peace was a solid moral call. I mean, was Rorschach all that wrong in the end? Does the fact that he’s completely insane and hates women and uses terror to collect information and thinks queer people are degenerates and….okay, you get the picture…does any of this matter given the gravity of the “alien” genocide you’ve just seen perpetrated on humanity?

Ultimately, you, as the reader, are asked to make your own judgment about one simple question: is world peace achieved through the threat of terror not superior to freedom ensured by a violent, murderous fist?

Okay, not really. That’s the child’s version of the question. The real question Alan Moore is asking is: who are the real fascists in Watchmen - the all-powerful superhero peacemakers or the violent, streets-based Far Right superhero who growls “freedom” at the night?

Wait, wait, wait, no, that’s not right either. Let’s try it one more time.

The real question Watchmen wants you to answer is: why the fuck do you think the world is so black and white that vigilantes, inherently fascistic forces, are the solution to society’s overwhelming problems?

Yeah, that’s the joke here, in Moore’s mind. Superheroes offer easy solutions to complicated problems. They’re no different than political slogans and holy books, utterly lacking in nuance and naturally resistant to ambiguity. They’re good guys, they fight bad guys, and that’s just the way the world works.

Except, of course, it’s not.

There’s no obvious way to get out of this article, I’m finding. Watchmen is so sprawling, so complicated, so nuanced that I could go on and on about it for another fifty pages and probably not get bored. That’s why it’s considered one of the greatest books of any kind ever written. Another reason it’s one of those greatest books? How it involves the reader in its story.

There are so many different ways to think about the role of an audience in art. I’ve heard from many brilliant artists how irrelevant their audience is to their process and, fine, I accept that’s true for them. Sometimes, it’s been true for me, too. Every piece of art requires a unique approach on the part of its creator. But consider how Alan Moore uses Rorschach in Watchmen to signal what he expects out of you as you read his comic book. Without you, the story just doesn’t work. It’s all surface, visually as familiar as other superhero comics. Costumed vigilantes fighting bad guys, that sort of thing. For it to be more, you have to join the story. You have to become part of the conversation it’s trying to have about ethics and morality and the genre itself and, in a sense, choose your own adventure with every page you turn. What a thrill it is, too, to read a comic book or novel or watch a film or TV series that whispers, “Hey, you, sitting there on your couch, put down the Doritos and come with me, it’s time to go find out who you really are.”

That whispered voice is called ambiguity.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Wonderful. I love your thoughts. I think you hit the nail on the head.

It really is one of the best books ever written.

Part of Moore's genius is that Rorschach is perversely likable. Even lovable. I had to consciously stop myself from rooting for him. It's such a well-written, entertaining book that when the movie was announced I thought, how could a faithful adaptation go wrong?

But audiences do not want their heroes torn down. At least, not these kinds of heroes. Audiences turn to superheroes because no mortal is capable of doing a superhero's job. If the SUPERHEROES are hopelessly corrupt, there's no one left, and no hope for a just society.

So movies that subvert the genre always fail.

A brilliant analysis as usual, Cole. Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, and Kingdom Come are, of course, the three greatest comic book stories of all time, and not so coincidentally, all of them address police states, vigilantism, a complacent and fearful American public, and as you adroitly noted, the ambiguity of the tyranny of the just.

Scratch it all away, all the culture and the art and the stellar writing, and it comes down to those same old base monkey-brained primordial impulses...I Am Afraid, and What Can Somebody Do About It.

One wonders what our best literature might morph into, in a world without fear.