Q&A: Comics Legend Mark Waid Still Believes a Man Can Fly

With more than 1,500 comics behind him, from his beloved Superman to the iconic 'Kingdom Come' series, the writer reflects on his 40-year career and the state of superheroes today

Comic books were as much a part of my childhood as cinema was — and my life revolved around cinema — but something happened in the mid-Nineties that dramatically changed my relationship to the medium. First, I had spent half of a decade obsessively studying illustration, convinced I was destined to become a comic book artist, but right around nineteen it became obvious to me that, while I could get there — meaning, I could bring a story to life on the page, even do so with interesting composition and occasionally innovative flourishes (or so I thought) — it would never come as easily and naturally to me as it did my artist heroes. It was only then that I shifted all of my creative energy to the written word. The other thing that happened was a kind of mass fracturing that took place in almost every corner of the industry. Many creators launched Image Comics and then the two major publishers, DC Comics and Marvel Comics, exponentially expanded their title output to such a degree that my available reading time, bank account, and eventually interest just couldn’t keep up anymore. The final comic book series I purchased in issue form (I never stopped by graphic novels and other TPB collections) was a four-issue limited series entitled Kingdom Come (1996). Stunningly painted by Alex Ross and written by a writer I’d become familiar enough with by that point named Mark Waid, it was, for me, the final word on superheroes for me for a very long time. Its vision of a dark future, in which the heroes of my youth were forced to come out of retirement to contend with a more violent new generation of “heroes” — even Superman had lost his faith, as it turned out — spoke to me about both generational and ideological conflicts. About the meanings we imbued so many of our old heroes with — both real world and “super” ones — and their dissonance with the increasingly harsh ugliness of our contemporary world.

Over the years, my love affair with comic books has been rekindled by many brilliant writers and artists. I’ve been fortune enough to have several of them have join me for my artist-on-artist conversation series. Today, I add Kingdom Come’s writer, Mark Waid, to the list.

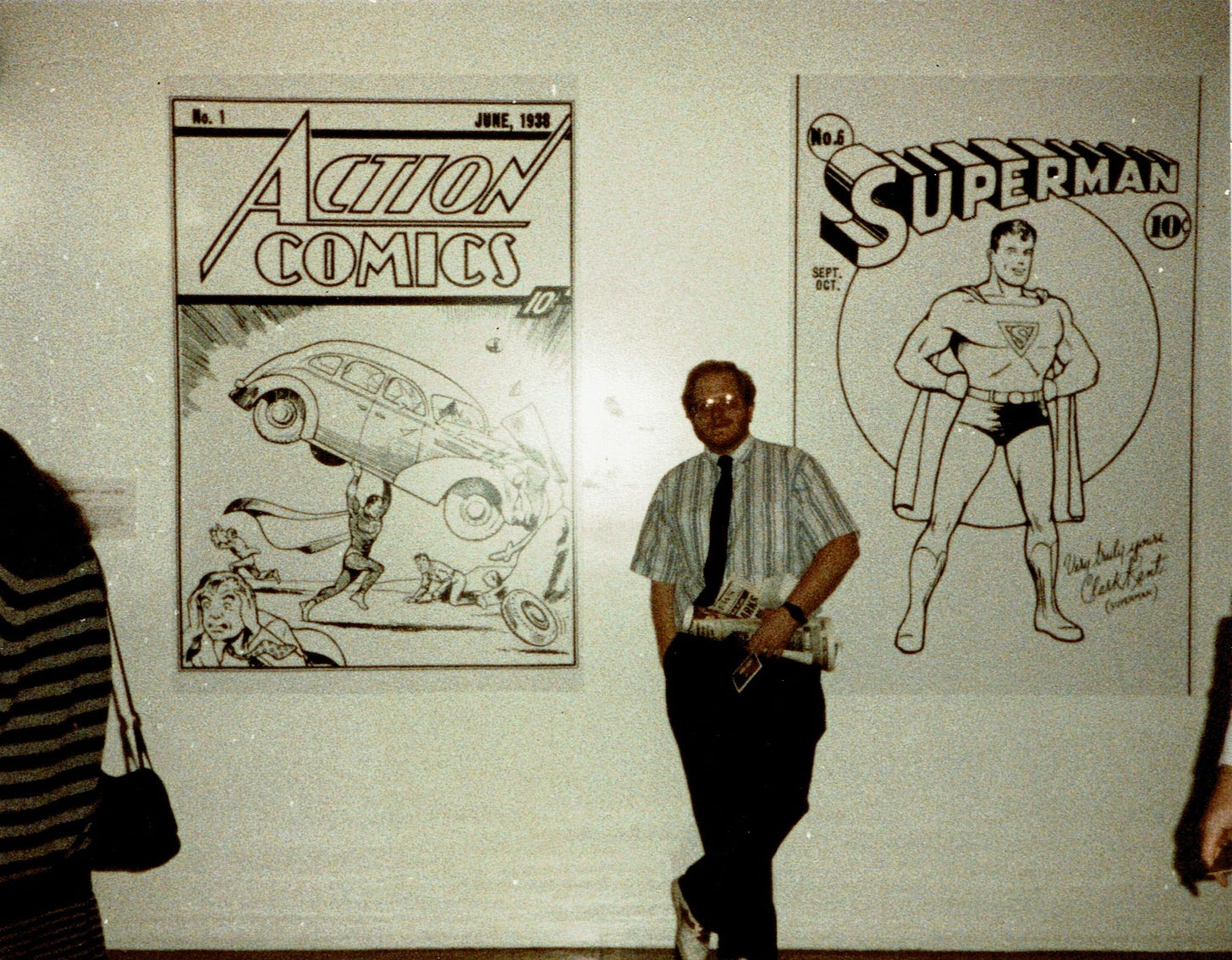

Mark is far from just the guy who wrote one of the most iconic comic book stories of all time, a feat that you’ll find he has complicated feelings about today. He began his career as a comic book editor in the Eighties, eventually landing at DC. But by then, he was already freelancing as a writer. In fact, his first published comic story (1985) was about Superman, a character, you’ll learn, that supersedes all others in his personal and professional life. By the Nineties, he started a celebrated eight-year run on The Flash. There was a lot of other work during this time, including over at Marvel, but it was Kingdom Come that truly launched him into the comics stratosphere, I think it’s fair to say. In the decades that have followed, he’s become a key creative voice at DC and Marvel Comics and written numerous iconic series and storylines including two favorites of mine - Superman: Birthright (2003 - 2004) and the creator-owned Irredeemable (2009 - 2012; Boom!).

The conversation you’re about to read is a sprawling interrogation of Mark’s own creative origins, his relationship to some of his most lauded works (such as Kingdom Come), and — most interestingly now that our chat is over and I’ve really digested the ramifications of so much of what he said — the state of superheroes both on the page and screen.

For storytellers working in mediums outside of comic books, I cannot stress enough that so much of what Mark and I discuss is applicable to all narrative art forms.

COLE HADDON: You know a thing or two about the multiverse, Mark. Is there a variant of you out there who isn’t a comic book writer and, if so, what are they doing with themselves every day?

MARK WAID: He’s probably a therapist. I’m pretty good at listening to people, and I’m told I’m unusually empathetic, which is something all writers should be striving for. He could also be a broadcast journalist/voice actor, as that was my goal as a teenager who had exactly zero ambitions of becoming a comic book writer.

CH: Let’s talk about your secret origin then, just to keep building questions off of lazy comic book references. You’re from Hueytown, Alabama, a corner of Birmingham I passed through for work once — god! — twenty-five years ago. I only remember this because Huey Lewis and the News’ “I Want a New Drug” was inexplicably playing when I saw the welcome sign. What was your childhood like?

MW: Chaotic. My parents split when I was about eight. Looking back, the red flag was the expensive magic kit they gave me the weekend before to soften the blow - yeah, there’s a magician Mark Waid out there, too, annoying people. There wasn’t any real discussion about it. My mom just loaded my three-year-old sister and me into the car and drove us to her parents’ place. Along the way — and this memory is burned into me forever — she ducked into a convenience store for a few minutes — it was okay to leave kids in the car back then — and came out puffing on a cigarette, something I had never seen her do before. I just gaped at her, and her response was to say, “Guess you don’t know everything about me, do you?”, which, looking back, was my first encounter with the concept of a secret identity.

CH: Wow, that’s a whole Raymond Carver short story in a single paragraph. One of those unfortunate, painful memories that also, as you suggest, can’t help but shape you in some way you can’t understand until years later. Did you remain in Hueytown and did your mother continue to provide you so much fodder for future characters and therapy sessions?

MW: We ping-ponged all over the Birmingham area with lengthy side stays in Tupelo, Mississippi, where my maternal grandparents — and, eventually, my mother — lived. I was bumped up a couple of grades along the way, so I never really got to make close friends or be considered anything more than the shy, bullied bookworm. We also went to live with my father and new stepmother about three years after the divorce. My mother — who worked two jobs, but was a woman in Alabama in 1971 and therefore paid lousily for crap jobs — decided she literally couldn’t afford to support us. That made perfect sense when I was a kid, but as an adult, I have my doubts and suspect that there was at least a little “I wish I could be totally free” mixed in there even though she never gave us any doubt that she adored us. So, as a little feeling-unwanted vagabond who went to twelve different schools in ten years, it’s not hard to figure out why I gravitated towards superheroes, most of whom were orphans with few close friends.

CH: This seems like a good time to ask, when did you discover comic books in the midst of this chaotic childhood?

MW: When I was almost four, my father noticed that I was enraptured by this new TV show called “Batman”, so he thoughtfully brought me a Batman comic, which my mother and grandmother helped me read. This also sparked me to learn to read at an adult level within the year - I was a bright kid. I’ve been hooked ever since, even during those teenage years when most fans tend to gravitate away from the hobby. But those comics, in the chaos, were a constant, and those characters were almost like my imaginary friends when I was young.

CH: Earlier you mentioned you had “exactly zero ambitions of becoming a comic book writer.” Maybe not comics, but was storytelling part of the equation as adulthood stared you down? Who did you think you wanted to be?

MW: I had no real clue growing up what I wanted to do with my adult life, at least so far as I remember. I didn’t dream of pitching for the Yankees or being a rock star or whatever. And in no way was storytelling yet part of the equation. But there were two key moments that pointed me towards a future.

CH: Do tell.

MW: The first is my earliest memory, from December 3, 1968, sitting down to watch Elvis Presley’s legendary “Comeback Special”. Everyone in my family was a fan. We were watching in Tupelo, Elvis’ hometown, at my grandparents’ apartment, and while I probably didn’t articulate it fully at age six, deep down I realized in that moment that if another kid could rise from the depths of Tupelo to achieve great things like Elvis did, maybe there was room for two of us.

The second came when I was a fifteen-year-old senior in high school. We were living in the suburbs of Richmond, Virginia by then. My father was a middle-management guy for Gulf Oil who got transferred a lot. I was a mess. Largely friendless, being lobbed back and forth between a mother and a father and stepmother who were doing the best they could but couldn’t figure out how to help me find a sense of self-worth, feeling strongly that no one on Earth really cared about me. I was staring down the barrel of a future that had no direction and held little hope. It really, truly was all I could do just to get through each day.

On January 26, 1979, everything changed. I went to see Superman: The Movie. I remember being excited. I’d been reading comics since I was four, and I liked Superman, though not as much as Batman and Robin or Doc Savage or, for that matter, pop music or magic tricks or TV or any of the kinds of things that interested me at that age. I sat down for the 3:20 show, the film started, the music swelled - and the instant that giant S-shield boomed onto the screen bigger and brighter than I ever could have imagined it, I was transfixed. And by the time the end credits rolled, I’d found the hero I’d needed. It didn’t matter that he wasn’t real. I wasn’t crazy, I knew that. What mattered to a kid who felt unseen was that Superman cared about everyone in the world, without exception, without judgment. I’d walked into that theater with a very short future ahead of me, and I’d walked out feeling safe and inspired in Superman’s orbit. Without that, I can promise you I would not be here today, and I can say with utter conviction and without hyperbole that Superman saved my life - and I knew that afternoon that whatever I was going to do with the rest of that life, it was going to somehow have to do with Superman.

“I can say with utter conviction and without hyperbole that Superman saved my life - and I knew that afternoon that whatever I was going to do with the rest of that life, it was going to somehow have to do with Superman.”

MW (cont’d): On January 26, 1979, everything changed. I went to see Superman: The Movie. I remember being excited. I’d been reading comics since I was four, and I liked Superman, though not as much as Batman and Robin or Doc Savage or, for that matter, pop music or magic tricks or TV or any of the kinds of things that interested me at that age. I sat down for the 3:20 show, the film started, the music swelled - and the instant that giant S-shield boomed onto the screen bigger and brighter than I ever could have imagined it, I was transfixed. And by the time the end credits rolled, I’d found the hero I’d needed. It didn’t matter that he wasn’t real. I wasn’t crazy, I knew that. What mattered to a kid who felt unseen was that Superman cared about everyone in the world, without exception, without judgment. I’d walked into that theater with a very short future ahead of me, and I’d walked out feeling safe and inspired in Superman’s orbit. Without that, I can promise you I would not be here today, and I can say with utter conviction and without hyperbole that Superman saved my life - and I knew that afternoon that whatever I was going to do with the rest of that life, it was going to somehow have to do with Superman.

CH: Do you ever feel that, with your work, you’re trying to pay down that debt or even extend a similar gift of grace to someone else?

MW: Yeah, to some degree. When people bring Kingdom Come or Superman: Birthright up to me at signings and say, “I never liked Superman until I read this,” I always tell them that I love Superman and I wanted to show them why in hopes they’ll love him, too.

CH: Fun story that you might find amusing. I used to be an arts journalist, a stringer for Village Voice Media. I sat down for a round table with a guy who had just directed an adaptation of one of the most celebrated graphic novels of all time. This was early 2009, one of my last freelance gigs as my screenwriting work had started to take off. The subject of Superman came up. Specifically, would this director ever want to helm a Superman film? He then proceeded to explain how terrible of a character Superman was. He had no arc, no conflict, no drama. Not interested. No, he told us, Thor was the character he would love to direct a movie about. As you mull that anecdote, can you tell me why you love Superman so much? He’s a character who, in my mind, seems to only become more and more relevant as he ages.

“Just because you’re a frat bro with a camera doesn’t mean you’re qualified to direct a superhero movie, nor does it make your edgelord take on superheroes particularly insightful.”

MW: I hear you. Just because you’re a frat bro with a camera doesn’t mean you’re qualified to direct a superhero movie, nor does it make your edgelord take on superheroes particularly insightful. Here’s why I love Superman - his greatest superpower isn’t flight or super-strength or invulnerability. It’s his selflessness. Here’s someone who could have anything, take anything, rule anywhere or anyone he cared to, and instead he uses that power exclusively to help other people.

Every time I hear someone bitch about how Superman has no “conflict” or “drama,” my eye roll could power Los Angeles for a day. No conflict? Every moment of every day, he has to choose who to save because he can’t be everywhere all at once. Imagine living every waking moment as a doctor forced to prioritize an emergency room as big as the world. That’s a heavy weight. No drama? He has to hide who he really is simply in order to function in the world and to do his job well and stay stable. Clark Kent is an emotional necessity if Superman wants to feel of us rather than apart from us. Moreover, Clark is a necessary disguise because Superman requires an unfiltered view of the human race and its needs and wants. Otherwise, he’s Tom Brady at a sports bar 24 hours a day, surrounded by fans and sycophants who can’t help but make him feel apart and alone and disconnected because of his stature. There’s no one else quite like him in the world. His eyes can see colors that there are no names for. They can tell whether or not you’re being honest by watching how the synapses fire in your amygdala or smelling your pheromones. He and only he knows the sound bullets make when they bounce off of living flesh. The hurdles he faces when it comes to feeling like a part of the human community are immense.

Of course he remains relevant. He stands for empathy, kindness, and acceptance in a nation that places less and less importance on these virtues every day. He’s what we want our better natures to be. Superman reminds us that kindness is power. That compassion is power. That helping others in need without expectation for reward is of benefit to us as well as to them. That bullying and punching down is just wrong. These are values that he teaches us as children that we’re able to carry with us the rest of our lives, and we’re reminded of this every time we see someone wearing his “S” on a t-shirt or a baseball cap. That “S” symbol is our silent acknowledgment to one another that we recognize those values as achievable goals we should be striving for.

CH: I want to ask about the multiverse some more, which you know a thing or two about. Once upon a time, it was novel and almost entirely the domain of comic books. But it’s an idea that has permeated pop culture for the past several years, from Marvel and DC films, to TV, and was even at the heart of last year’s Best Picture winner Everything Everywhere All at Once. Do you feel the ubiquity of it has robbed the narrative device of the potency it once had?