Q&A: Comic Book Artist Colleen Doran Did It Her Way

The 'A Distant Soil' creator discusses how she carved out her own path in comics over more than four decades

One of the things I enjoy most about 5AM StoryTalk’s artist-on-artist conversation series is pushing myself to explore the creative process in mediums I don’t work in or necessarily understand nearly as well as I do others. Comic book illustration is one of them - which is why I was so excited when my friend Rantz A. Hosely, VP of Editorial at Z2 Comics, offered to introduce me to Colleen Doran.

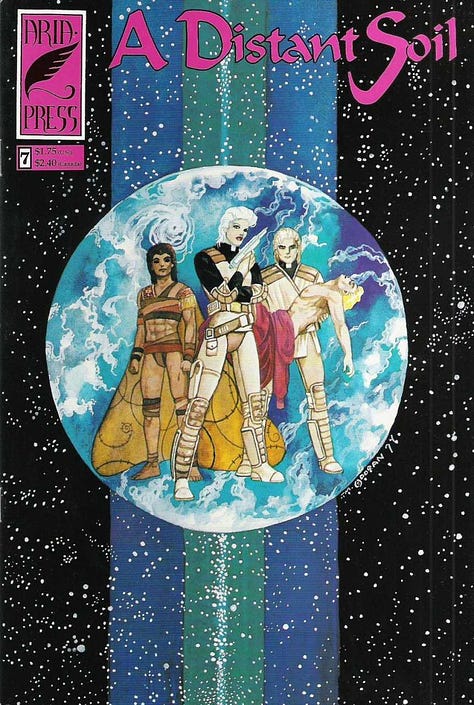

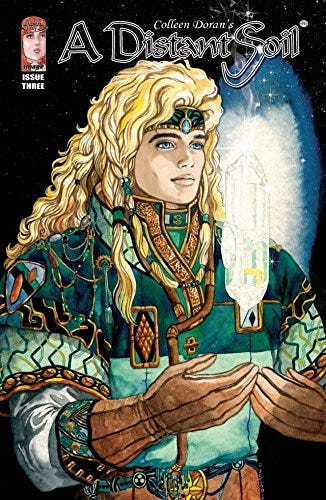

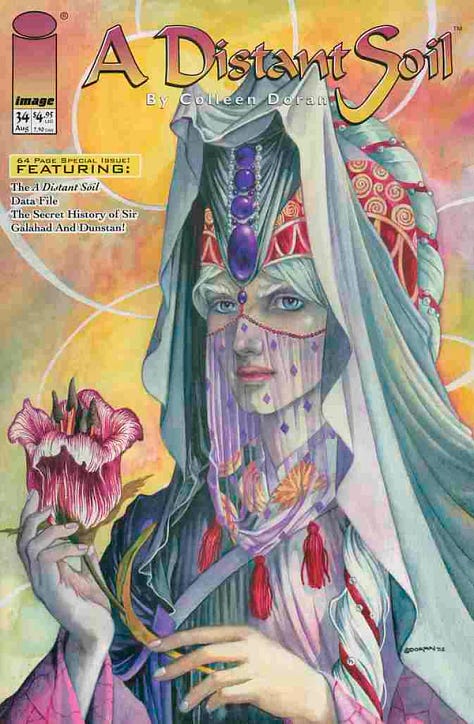

Colleen has been professionally illustrating and writing comic books for more than four decades. She began her career while still in her teens, working in the — as you’ll learn in our chat — often seedy and shady world of independent comics before she began to draw for the major publishers. I became more familiar with her work when it began to appear in DC’s Vertigo titles such as Sandman. I reference Sandman, in particular, because Colleen’s collaboration with its creator, Neil Gaiman, has blossomed in the 21st century. The two work regularly together, and she’s won two Best Adaptation from Another Medium Eisner Awards as a result - for Neil Gaiman's Chivalry and Neil Gaiman's Snow, Glass, Apples. Through it all — and I mean through it all, going back to the ’80s — Colleen has also published her creator-owned series, A Distant Soil, a space fantasy she started working on as a child. It’s her most enduring work and is beloved by a legion of fans. I can’t think of many storytellers who have accomplished anything similar over such a period; you have to start referencing people like Ursula K. Le Guin and George Lucas to find appropriate comparisons.

While you might not be a comic book fanatic or an illustrator yourself, I expect artists of any kind will find a lot to learn from Colleen’s almost religious commitment to her craft and pushing herself to new heights. This is a nuts-and-bolts explanation of how one artist did it, in a medium dominated by men, and did it her way instead of theirs. It’s an inspirational read in so many ways.

COLE HADDON: Colleen, I hope this isn’t too simple of a question to kick things off, but can you remember the first artist who made you want to draw?

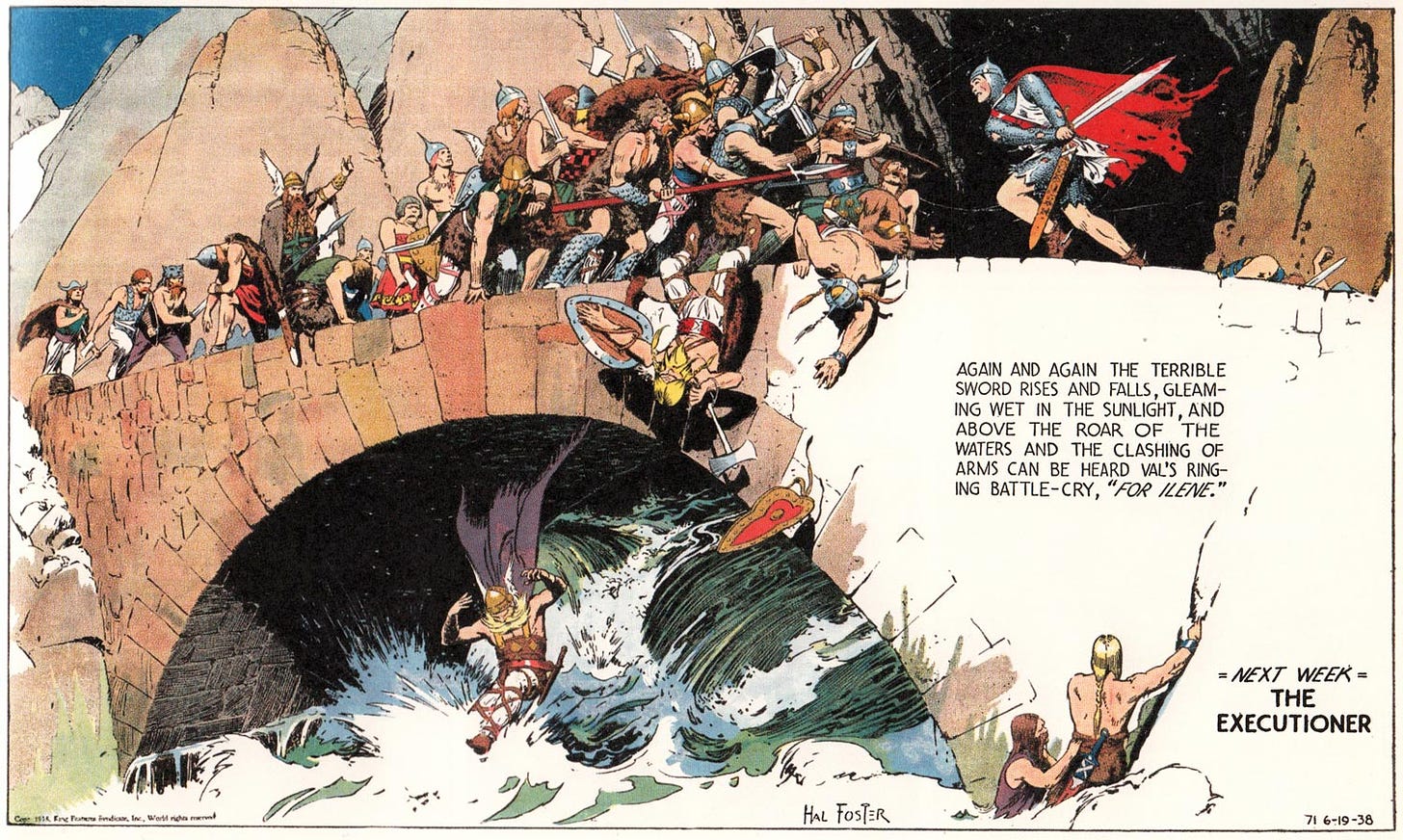

COLLEEN DORAN: Well, the first artist who really made me want to draw was comic strip artist Hal Foster. Way back in the 1970s when I was a kid, the Prince Valiant strips were collected and reformatted in early graphic novel style, and these were distributed at Scholastic Book Fairs. Everyone thinks graphic novels are new and that graphic novels being sold to kids happened yesterday, but that’s just not true. It was a thing even when I was a kid. I read the hardcover graphic novel collections so often the spines split apart. I wanted so badly to draw that well and to be a part of that world.

CH: So, Prince Valiant was your comic book gateway drug, then?

CD: I was obsessed with Prince Valiant and would clip the strips out of the newspaper and keep them in a little box. My family was pretty poor, so I was doing things like going through people’s trash to get the newspaper, or picking through piles of firewood to dig through the kindling to see if Prince Valiant strips were stashed in there. I would also grub up soda bottles to redeem to get nickels to buy comic books. I loved Aquaman stories, too. But then, we moved to a really small town of about 1,500 people, and there were no shops that sold comic books. Any time we went into town, I’d be at the 7-11 looking at the spinner rack. I barely saw any comic book for years.

CH: Christ, that sounds like hell as a kid. So, how did your passion for Hal Foster and Prince Valiant manifest on the page at such a young age?

CD: I started drawing and entering competitions for both writing and art from age five. I remember getting very angry every time someone would demand to know if my mom did the work for me or something. Or if I copied something. That really pissed me off. It also set me back.

CH: How so?

CD: For a long time, I thought using any kind of reference was cheating somehow and would only draw from memory using the construction method! Anyway, I thought maybe I’d be a Disney animator, but I wasn’t really sure if people made a living as artists. I kept reading stories about starving artists. And like a lot of kids, I assumed I’d end up a doctor or an astronaut. I worked in a vet as a kid, and they would let me help out in surgery. I think everyone assumed I was going to medical school.

CH: Then, what changed?

CD: When I was twelve, I got really sick and a family friend gave me a big box of comic books to read while I was stuck in recovery. When I saw that big pile of comics, that was it, that was all I wanted. I planned my entire future around it. I studied everything I could find, and that wasn’t easy in the days before the internet, and at a time when comics were not considered good for kids. It was shameful to work in comics, everyone ridiculed you for reading them. Now everyone goes on and on about what a “privileged” job it is. Utter nonsense, nothing about working in comics when I went for it was privilege. Fandom was as outsider as you could get. If you were a nerd, you were a complete outcast.

CH: If you don’t mind the detour, I’m curious if you think the comic book medium has lost anything now that it’s so mainstream. What I mean is, do you think that outsider status, a kind of punk-art nerd quality, helped revolutionize the art form during the ’80s and ’90s in a way that would be more difficult today when comics are such an accepted art form?

CD: That’s a good question. It’s also a tricky subject as many people in fandom consider themselves outsiders, but it’s not outsider culture the way I remember it.

Back in the day, fan culture was complete social poison. Now, it’s a faux escape from mainstream culture, and I say “faux” because it is the mainstream culture. If you were into fandom in the past, you were making a tough choice because almost everyone you knew was going to dump on you for it. You had to really, really love this stuff with an obsessive love. The books were hard to find, other fans were hard to find. The kind of people who call themselves nerds and geeks today are the kind of people who would bash in the heads of nerds and geeks back in 1976.

CH: Absolutely, except I’d say the same even about kids in 1986 and 1996 – at least from my experience.

CD: Definitely, I mean I was just leaving college about then.

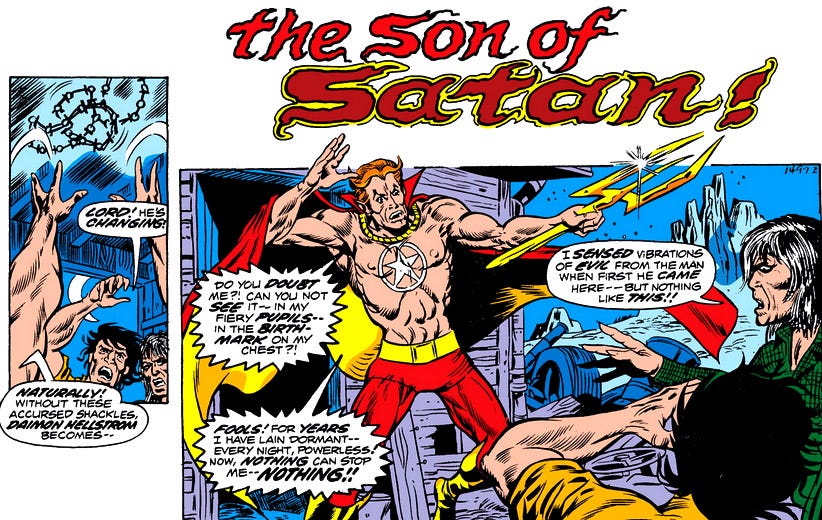

Everything about working in larger company comics publishing is more corporate on every level. The larger company editors are more careful about political content. I was having a talk with some of my readers the other day about whether or not you could even publish a comic at Marvel called Son of Satan in today’s climate, yet that was first published back in the 1970s - and I loved it.

CD (cont’d): I turned in a script a while back and an editor asked me, “Now what did our characters and readers learn from this experience?” We’re getting the kind of editorial direction you would expect in YA book publishing rather than in comics. I’m not saying that’s good or bad. I’m just saying it’s really different because in all my years in comics publishing, not one editor was thinking about “what the reader learned”. They were concerned if the reader was entertained - and these concepts are not always twinned.

The material people were creating in the undergrounds was very edgy, very rock and roll, too. The whole scene could be pretty dark at times, and a typical convention was 150 people in a hotel ballroom or church basement picking through grubby boxes looking for back issues. That was about it. It was all about comics and nothing else.

CH: My first comic book convention was back in, oh, 1989, maybe 1990 in an AMVET Hall that didn’t have windows. The situation didn’t improve, if we can call it that, for several years. I can still taste that cloistered air. You lost track of time in there, and hours later you’d emerge confused by daylight. But there was also a purity to it, I think.

CD: Oh my God, yes, the early conventions were so seedy, and finding comics was about going to something that was essentially a nerd flea market. Fandom today has no idea how it was, you know. The shows were often pretty smelly or dusty, and no one was there for any reason but comics. Of course, you’d have a minority of people doing costumes, and a lot of the costumes were the kind of things that would get you thrown out of public places now.

And there was no awareness of proper boundaries with kids. I was part of a group of about half a dozen kids, often the only kids at local shows. No one thought twice about pushing adult material at us. I don’t think I realized how inappropriate it all was until years later. My mom often accompanied me to shows, but I can tell you the minute she wasn’t around, things could get rough.

CH: I’m going to come back to how the comics industry has changed later on. But, getting back to your secret origin, I love the nostalgic way you describe your early love affair with comics.

CD: It’s all about the love, baby. I remember being really struck by an issue of Son of Satan drawn by Russ Heath, which I just mentioned, and some ads for a King Arthur series by Nestor Redondo. I spent years trying to dig up that King Arthur series, but we all know now it never came out. I drew poster-sized versions of Redondo’s King Arthur art for papers I wrote about King Arthur for English class. I not only wanted to tell good stories, I wanted to draw beautifully.

CH: How did this instinct actually show up in your work?

CD: I was trying to use unconventional layouts and panel design in my work, as I’d seen in the works of early strip artists like Rose O’Neill. And I got a lot of pushback, let me tell you. But then, a friend of mine named Leslie Sternbergh – who was an underground cartoonist and later an artist for Mad Magazine – said to me, “This stuff reminds me of your work,” and she introduced me to Japanese comics. In particular, an artist named Yasuko Aoike. And I said, “Hey, people keep telling me I can’t do stuff like this and here’s a whole bunch of artists doing what I am doing, and you’re telling me I can’t do it?” So, that was a big push to keep going in the directions I wanted to go.

I was a big fan of classic shuojo manga for a while, and though I don’t follow it anymore, it was important to me to see people doing the kinds of things I kept trying to do, the – for the U.S.A. – unconventional storytelling technique, the decorative art. While I ultimately rejected the hard-core deconstruction technique that a lot of Western artists use these days, I think Frank Miller hit a great balance of Western and Eastern influence in story with his 1980s comics. I spent a lot of time studying his technique, though it’s probably not obvious.

CH: Can you remember what motivated this need for innovation in you? What about the form did you maybe find limiting or maybe even stifling to your ambitions as a storyteller?

CD: It was just bizarre to me that there were these weird restrictions on how to tell a story coming from people who ought to know better. Some editors insisted on six panels per page. They had no interest in anything but standard formulas, they didn’t want anything new or different. Some of these people were just lazy and/or controlling.

For example, I didn’t like inking one of my works with a brush, and an early indie client kept insisting I use a brush. And I liked using a pen. The editor insisted no artist in comics uses a pen, which, back then, few comic artists did. And I said, “Terry Austin uses a pen.” And he said “Well, you’re no Terry Austin.” Which was both belittling and stupid, because I’m also no Alex Raymond, but this didn’t stop this editor from insisting I use a brush like Alex Raymond.

To this day, I almost never use a brush for inking, but what a dopey thing to tell someone in 1983 - “Well, if you’re not as good as this artist, you must use this tool because I say so.” There was nothing there about growth or style or appropriateness for the job. It was just about control.

CH: To be frank, you could be talking about a lot of the Hollywood development experience. In some ways, I suppose I’m glad to hear about it happening in other industries.

CD: People who aren’t very creative are attracted to creative people. They fool themselves into believing they are the real minds and we are just tools they use.

I remember in one job, I used abstract, geometric shapes in the background of a club scene to represent music - and the editor was utterly baffled by this. Some just didn’t want to deal with anything they weren’t familiar with and that didn’t fit a formula. Which is understandable to a degree, but it is lazy. This wasn’t just a mainstream editor thing, though, which is why I think a lot of it was about control early in my career. Some of these small press dudes were 100 times worse than the mainstream editors.

CH: I think it’s this kind of formulaic nonsense I suppose I was getting at when I asked if there was anything limiting about the form you bristled against.

CD: There’s nothing limiting about the comic art form. It’s just that some people are there to do a job and some people are there to try things, to do different things - and if you’re stuck with colleagues who are just there to do a job, you’re going to be frustrated.

It’s very strange to speak to some of these people now, I don’t think they remember how their attitudes were, or how stifling they could be. I appreciate that things have changed. I have no hard feelings – well, okay, some – but when I tell kids today, “Well, some editors wanted us to stick to six panels per page,” they look at me like I’m speaking Urdu.

CH: [Laughter] So, did you have a vision for yourself as an artist you were working toward and how receptive did you find the mainstream comic book industry to that vision?

CD: Well, I knew exactly where I was going as an artist as a kid. I wanted to learn and be very good at comics. That’s it. In 1979, a book was published entitled The Studio. It was about the arts collective of Bernie Wrightson, Jeffrey Catherine Jones, Mike Kaluta, and Barry Windsor-Smith. This thing was my blueprint for my entire future. I wanted to live in that world and make those works. This weird Pre-Raphaelite picture-making and comics existence in a cluttered studio with pictures pinned to the walls and peacock feathers in vases. That book was the key to the magic scriptorium.

CH: What I appreciate is how humble your ambitions were. It was about the art for you, which I suppose was as much about the time and the professional possibilities of comic books anyway.

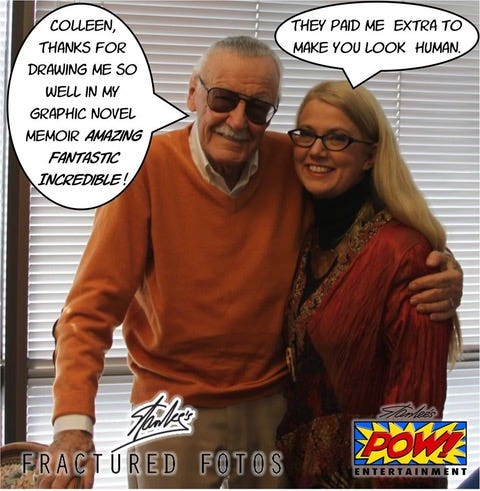

CD: I remember some dirty old man editor coming on to me and saying, “I’m going to make you famous.” I said, “I don’t want to be famous - I want to be good.”

I mean, really, who was truly famous in comics in 1980 except for Stan Lee? Fandom had puny ideas about fame back then, seriously. My dad had been a security guard for everyone from Led Zeppelin to Elvis Presley. I knew what fame was. I didn’t get into comics to be rich and famous. No one of my generation did. It’s nuts to want fame anyway. It’s often dehumanizing and gross. I was in comics for one thing, and that was to do my work. I absolutely loved comics. I loved drawing the human figure, and the idealized human figure was just glorious to draw to me. Storytelling, spending long hours at home in peace carefully crafting my work, that was what I wanted.

CH: I asked how receptive mainstream comic books were to your specific vision for your work.

CD: I don’t know if comics in general were receptive to my work back in the day because I was just this weird kid making up this big space opera that was oddball material back then. Everyone uses those tropes now, but almost no one was in 1979.

Mainstream comics is rough if you get stuck in the journeyman track, doing fill-ins, getting those last-minute gigs where you can’t do your best work – not getting the top inker to work on your pencils – you’re just never going to break out. I had a few career peaks, but way too many deep valleys.

CH: Why do you think that is?

CD: Some of that was my fault, some of that was circumstances beyond my control. I went for years with an undiagnosed auto-immune disease that really messed me up. I never knew when it was going to cut me off at the knees, and editors need reliable talent for monthlies.

The vast majority of my successful work didn’t come out of mainstream comics at all. My break working with Neil Gaiman came about because he’d read my goofy space opera A Distant Soil. When we met, he offered me a chance at Sandman.

CH: I haven’t cross-referenced every name in your oeuvre to compare, but I’ve been reading your work with Neil for a while now. It’s obviously one of your most important professional relationships. Why do you think it’s endured for so long and been so creatively fruitful?