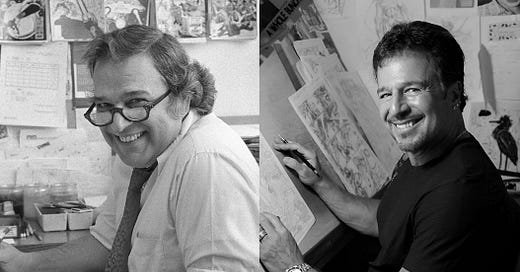

Q&A: Comic Book Legend John Romita Sr. Through the Eyes of His Son

John Romita Jr. breaks down everything he learned from his late father about storytelling, parenting, and the pursuit of greatness

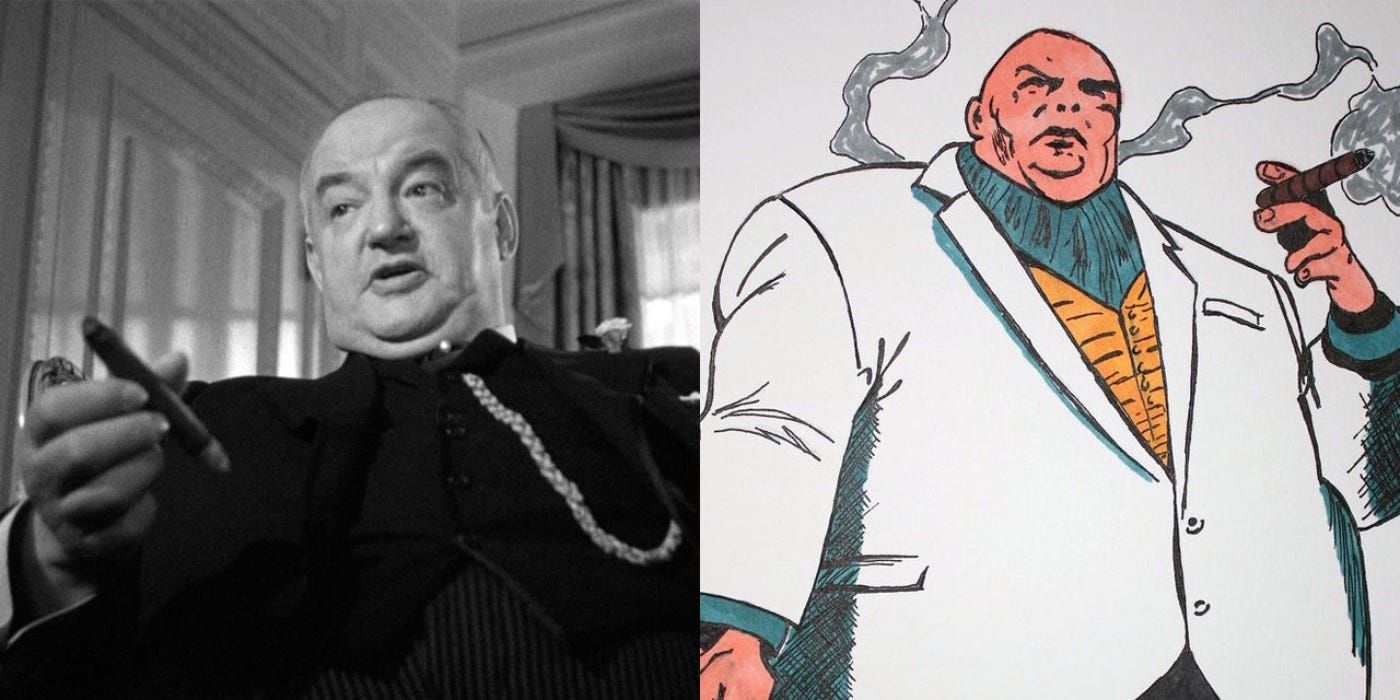

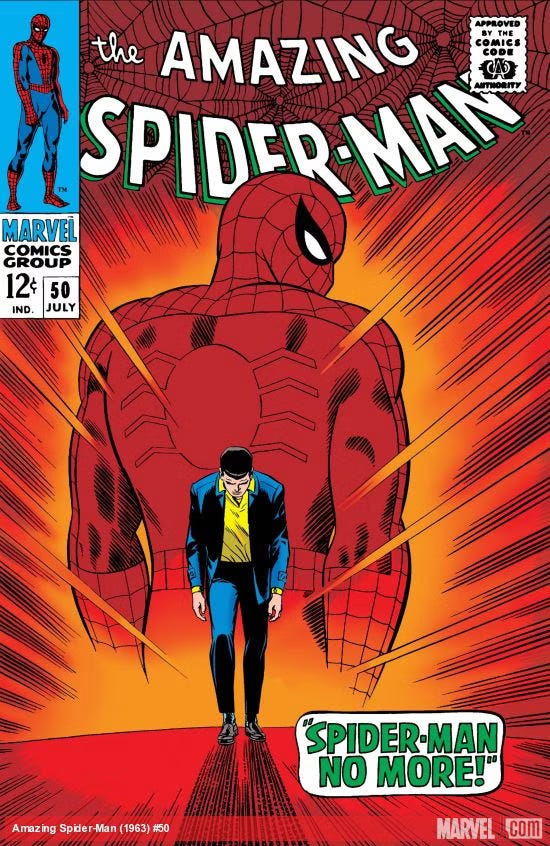

It was 1992 when I became truly aware of comic book artist John Romita Jr. That’s because that’s the year THE PUNISHER WAR ZONE came out, which I, sixteen at the time, reacted to with something along the lines of, “Jesus, I want more of that art in my eyeballs.” By contrast, I’d known who his father was since before I was ten. John Romita Sr.’s work had helped to define my love affair with Spider-Man, who was the only Marvel character who spoke to me in any way as a young kid. John Sr. is easily one of the most iconic comic book artists to ever live — his style as soaked in adventure as soap opera — and easily one of the most important in Marvel’s history. He co-created characters such as the Punisher, Wolverine, Mary Jane Watson, and the Kingpin. He also served as the company’s art director for many years. Sadly, the legend passed away in his sleep on June 12th of this year at the age of ninety-three.

Now, my father left us a few years ago. My mother four years before that. I’ve never really recovered from their deaths. And so, when I read the news about John Romita Sr., I felt compelled to text his son my condolences. John Jr. and I had met a decade earlier and flirted for a while with a collaboration. In due course, our texts about loss evolved into an opportunity for us to discuss his father’s impact on his life - both as an artist and also as a father, as I knew John Jr. had his own children. John Jr. agreed, all too happy to discuss, in his words, “the greatest man I’ve ever known.”

John Romita Jr., if you’re unfamiliar with his work, is a forty-year veteran of the comic book industry. He’s illustrated more titles than I could list here, the vast majority of his work for Marvel Comics - though there was a rather glorious half-decade-or-so stint at DC Comics where he helped relaunch Superman and his singular, visceral style brought something refreshing to both Supes and Batman. If you’re not necessarily a comic book reader, you might best know him as the co-creator of KICK-ASS (along with Mark Millar).

If you’re an artist of any kind, I encourage you to pay special attention to the lessons John Romita Sr. taught John Romita Jr. about how to push your storytelling craft to the brink in the pursuit of greatness. While John Sr. didn’t necessarily deliver lessons, as you’ll find, they were internalized as such all the same by his son.

COLE HADDON: You know my dad is gone. In fact, both of my parents are. It’s why I felt compelled to text you when your dad left us back in June. I don’t think I’ve ever found a way to process not having them in my life, but what I do find helps is talking to other people about their parents. In your case, your dad is also a legend, I think it’s fair to say. I grew up with him in a way so many did. You’ve more than once called him the greatest man you’ve ever known. So, let’s just start with his childhood, or maybe even his father to go a little further back and expand on this father-son conversation. Do you know much about their relationship?

JOHN ROMITA JR.: [Laughter] We found out as adults that my grandfather was not such a wonderful guy. He was a hard-working blue-collar guy from Italy - but he was a philanderer, so to speak. He married my grandmother when she was fourteen and they had children when they were fifteen. But the end result is all his children became good children and that's the part that shows on his headstone, in my mind. It was a wonderful family.

CH: It seems as if your father made some choices along the way or had some experiences that perhaps helped him evolve away from the story of his father’s life?

JRJ: Yes, different even from his siblings. My grandfather called him a Martian because he was the artist and it came from nowhere. No other relative was an art aficionado. He was drawing the Statue of Liberty from manhole cover to manhole cover in the streets of Brooklyn. He would use chalk — which was chunks of sheetrock from an abandoned building — and he would draw the Statue of Liberty from manhole cover to manhole cover while the other guys were playing stickball up the block.

“My grandfather called him a Martian because he was the artist and it came from nowhere. No other relative was an art aficionado.”

CH: Needless to say, they didn’t see I to eye.

JRJ: No, my grandfather thought he was a weirdo. I'll never forget my father's choked-up eyes when he said, “Grandpa just said, ‘You were right. Kid, I was wrong.’” And my grandfather would never say that — ever — no matter how right my father was. But because my father did the right thing as an artist, my grandfather finally acceded and said, “You were right, he’s not a Martian.” But he called my father a Martian because he was the only artist in the family and he came out of nowhere.

CH: Yeah, I was that person in my family in a lot of ways. My father would say, “I don’t know who you are.” So, what was your earlier childhood like was the son of “John Romita”. For example, how present was his work at home?

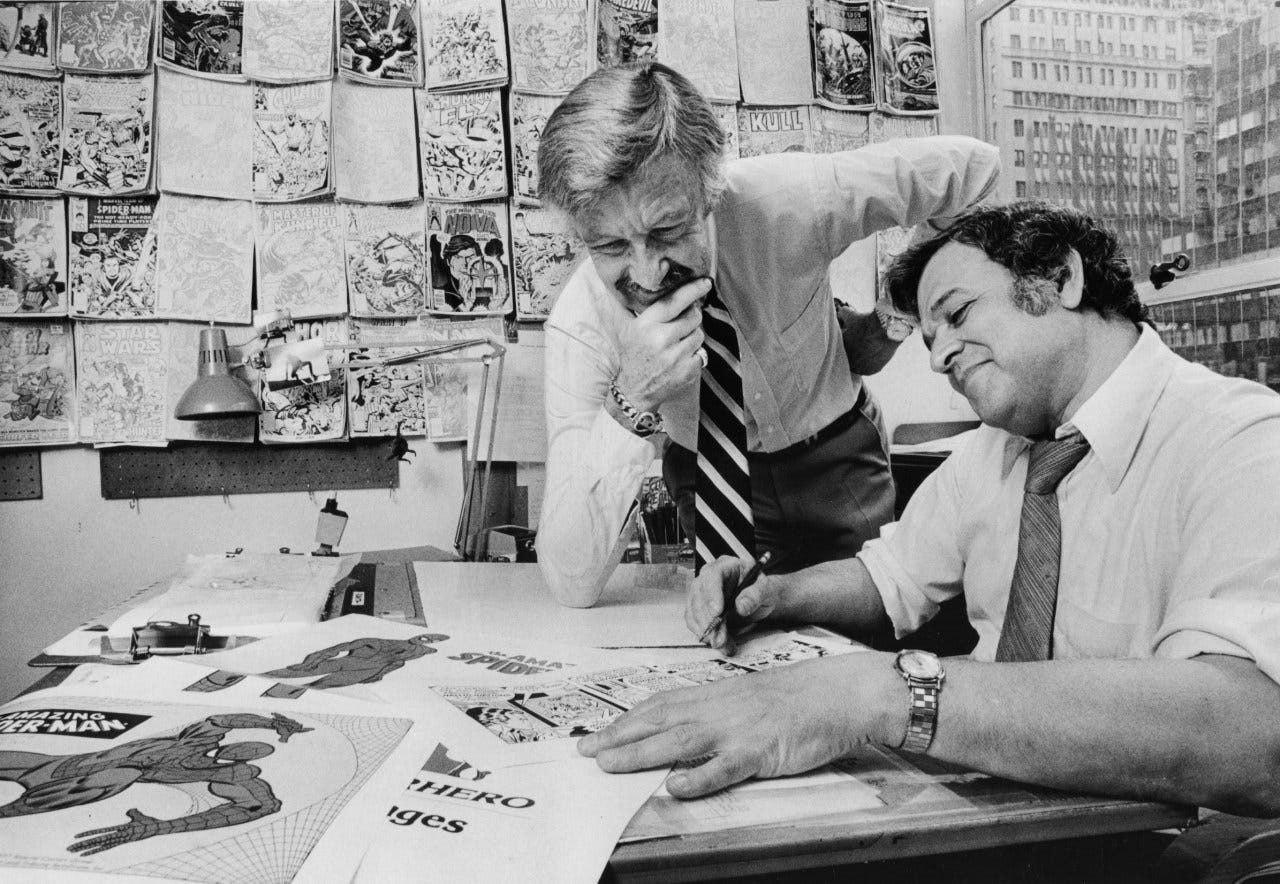

JRJ: My brother and I didn't find out what he was going through as a freelancer until later on in life. The hours he was working - we didn't we understand that because he would work at night while we were sleeping. But when he went from romance comics into adventure comics, so to speak, working on Marvel comics with Stan [Lee], that's when things changed.

CH: How so?

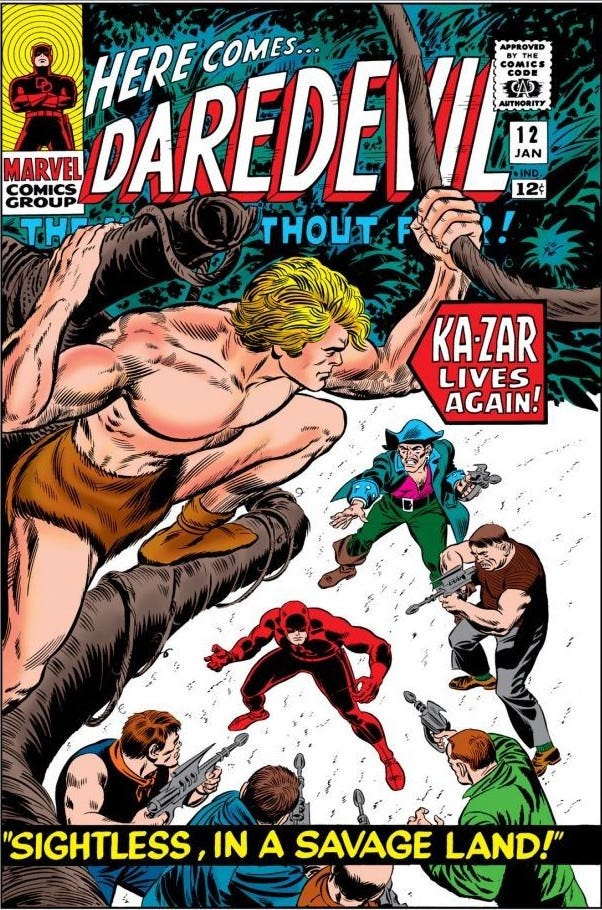

JRJ: There was this moment that I walked up into the attic — I was having nightmares — and I walked up into the attic while he was working through the night, and he was working on the cover for DAREDEVIL #12, and that was the first time I saw him working on a superhero image after all of the romance books that I ignored. I was crying from nightmares, and he told me to relax, sit down, “Check this out.” He went on to explain what a superhero was. It was, you know, the stuff you’d see in the barbershop — which was Superman and the Batman stuff — but I’d never picked one up. He said, “These are superheroes, too. This is Daredevil.” And then he explained Daredevil was surrounded by bad guys, and he told me that this guy was going to beat up all the bad guys, you know? “But also, by the way, he’s blind.” I think that — on top of everything else — my head blew off. I was hooked.

CH: Can you talk about how he raised you? You know, just as a father?

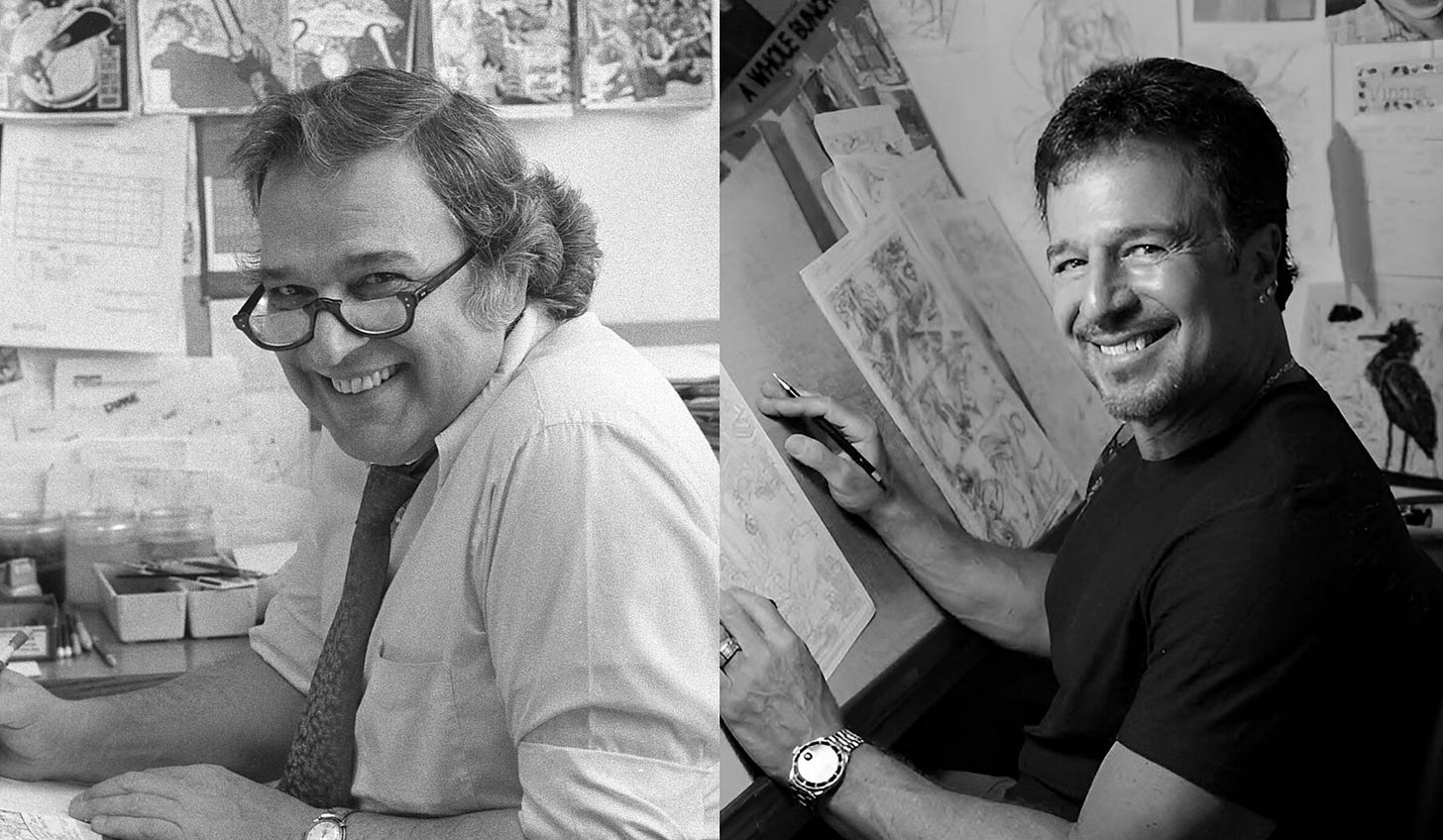

JRJ: The way he raised us was the way he just was. As an entity at the office, when he was an art director in the suit, he was level-headed. No pretense, no ego, just always level-headed. And he didn't brag about what he was doing as much as he was proud of what he's doing. He handled our lives the way he handled everyone at the office. Again, no pretense, just level-headed and wonderful. And his spare time was spent with us.

He taught me so many sports, baseball and all of the the other sports that we would play. When he couldn’t work, if he was having trouble with work, he would take us out for a game and teach us things. It was amazing that he thought of us before himself all the time. But when he struggled with work, we were also a means to an end. We would talk out whatever he was working on. Believe it or not, he would ask us questions. The simplest of answers might help him sometimes.

“When he struggled with work, we were also a means to an end. We would talk out whatever he was working on.”

CH: You mean, storywise?

JRJ: Storywise, yeah. It would be, we would take a drive to Grandma's house, which was a two-hour drive up to Connecticut. And as we were sitting there in the backseat, he would say, “You know, Stan’s asking me to do this. Spider-Man’s got to go through a pane of glass. Wouldn’t the glass cut him up?” I think I said, “Hey, Dad, if he wants to go through a pane of glass, then he should web his forearms up, so he doesn’t cut his arms.” And then he said, “That's not a bad idea.” It kept us from being bored, and it was a means to an end with him.

CH: It sounds like you didn’t have too much of an awareness about some of the stress he was under. I mean, I’ve read enough about life at Marvel at that time to know he was juggling a lot.

JRJ: He was so pleasant about his job. Never told us that he was working stupid hours per day and in the middle of the night he was up in the attic while we were sleeping. He rarely slept. And it was normal to him. To tell you the truth, it came back to bite me and that's because that became normal for me.

CH: It’s a blessing and a curse. I learned my work ethic from my father, too, but sometimes wish I’d paid less attention.

There’s a moment in your father’s life where he was offered more income, maybe more stability, if he stayed advertising. But he opted to go to Marvel because part of the deal was that he could have the freedom to work at home. Do you think he did that because he wanted to be around you guys more? Or was there another reason behind that decision?

JRJ: Good question. I think it's several, several reasons. One, to be home with the kids and another thing was he was working for DC Comics, doing romance books before he went to Marvel. Now he had done Captain America back in the fifties, with Stan briefly, and so he had a taste of super-heroes. I don't think he knew what he wanted to do, but the opportunity to work at home had been bounced off of him by several of his contemporaries, and because they had started in advertising and they had gotten into comics. So, yeah, the advantage would be to be around the boys and to be around his wife all the time. Yes, I would say that's a major part.

CH: Your father worked in comics, but was that something that was a relevant part of your storytelling education in your parents’ house?

JRJ: Remember, up until the sixties, he was working on romance comics – and then he went to work with Stan.

CH: Right, right, which would’ve been around when you were ten. Bit past bedtime stories at that point.

JRJ: My dad, now he was a cinephile, a big-time cinephile - and the storytelling aspect of my business really came from listening to him talk about the films we were watching.

CH: Really?

“The storytelling aspect of my business really came from listening to him talk about the films we were watching.”

JRJ: Instead of just sitting there watching a film and him having a beer or letting us be quiet while he went and did something else, he would sit there and talk to us about what was coming. With my brother, it was just a conversation piece. With me, it stuck with me.

CH: I want to hear more about this.

JRJ: I remember the film noir aspect of all the black & white films and the moodiness of the Philip Marlowe model — the rain dripping down off the hat — that all stuck with me because it showed itself as I went to art education in schools. I remember seeing that part of it play itself out in my work, saying, “Holy mackerel, my father was talking about this!”

But the interesting part was how he would talk about the films we were watching. As kids, we would sit there when we were bored because of the bad weather, and he would say, “This is a great movie, watch this scene.” It was all that way. He did it even with television. When television became a little bit more quality, he would talk about it and say, “Do you like this and do you like that?”

Some of the greatest films I ever saw were the ones he introduced me to. Just so many great films. 12 ANGRY MEN. THE BIG COUNTRY with Gregory Peck and Charlton Heston. He would explain cinematography to me — because I didn’t know what cinematography was — because there was this fight in THE BIG COUNTRY. Between Peck and Heston out in the middle of nowhere in this gigantic field. You think it's going to be the standard stuff, but then the director pulls way back and you see how big the country is - to coin the phrase. All you hear is the sounds of the fists. That kind of thing stuck with me.

JRJ (cont’d): So when we would watch old film — well, now they're old, but at the time they weren't old — he would talk about the film and we would get an education. My brother's education was being a cinephile. Mine was storytelling. It stuck with me. It’s so ironic that now it's my strength. I don't know if he was intending on me becoming a great storyteller or if it was just casual conversation when we were bored.

CH: I’m sorry, but this is just amazing. I have two questions about what you’re telling me. The first is about your father's relationship to these images and what he was telling you, which is - did you ever catch him using what he was teaching you in his work? You know, where you looked at an image and thought, “Hey, that's that's what you taught me. You know that from that that film.”

JRJ: Yes, yes, yes. Also, the familiarity some of the characters he would use.

CH: What do you mean?

JRJ: Like, thugs. He would use the image of some thug’s face that I'd seen in some of the films. I remember, I said, “Dad, I know that guy. I’ve seen his face!” And he says, “Yeah, that’s Sydney Greenstreet. He’s the Kingpin.”

CH: Fantastic. I knew Greenstreet was an inspiration, but hadn’t understood why.

JRJ: The storytelling aspect - he wouldn't tell us what he was putting in the book. But when we would read it, there was some familiarity. I'd say, “Wow, I've seen this. That’s from this movie.” And he would say, “Yeah, think about it. That’s a great scene, isn’t it? Well, this is the imagery from that scene.” You know, the dark shadows and the mood. Because Stan ultimately was the one who said to him, “You throw this up as much as you want into the wind and play with it. I'm just making a suggestion. But here's what you need to do. You need to get to this point to this point, and you play with it.” And then my father would literally tell ninety percent of the story. Yeah, it was familiar. We could see it.

CH: The other question I mentioned a moment ago is about your education as a storyteller. It’s a word you keep coming back to – storyteller. So, your dad was clearly your first teacher as a storyteller. But did he also teach you about illustration along the way, or was it just, you know, how to think about and tell stories?