I Want to Break Free (From Your Lies)

From Freddie Mercury to 'M*A*S*H', to Irving Berlin and my own grandfather - a partial, fragmented, and often contradictory history of America's complicated relationship with drag

Queen’s video for “I Want to Break Free” was released forty years ago this week. There’s a moment toward the beginning of it in which session musician Fred Mandel’s keyboards precede the appearance of an old vacuum that slides into a room, back and forth, as the camera then rises toward the woman wielding this housekeeping super-weapon. The poppy keyboards’ effect is something akin to the Jaws theme, signaling something naughty is about to happen. And it does when it’s revealed that the woman in the tight black leather skirt, pink sweater, and big hair is none other than the British band’s lead singer – Freddie Mercury.

I can recall the first time I saw this mustached man dressed in drag on my family’s TV screen, though I can’t tell you the exact year. I’d become a Queen fan in 1985, when The Highlander was released, a film that the band provided the soundtrack for, so I expect it was a year or two after that. What I am sure about is, it wasn’t in 1984. That’s because MTV initially banned it for being, in Queen guitarist Brian May’s words, “too homosexual”.

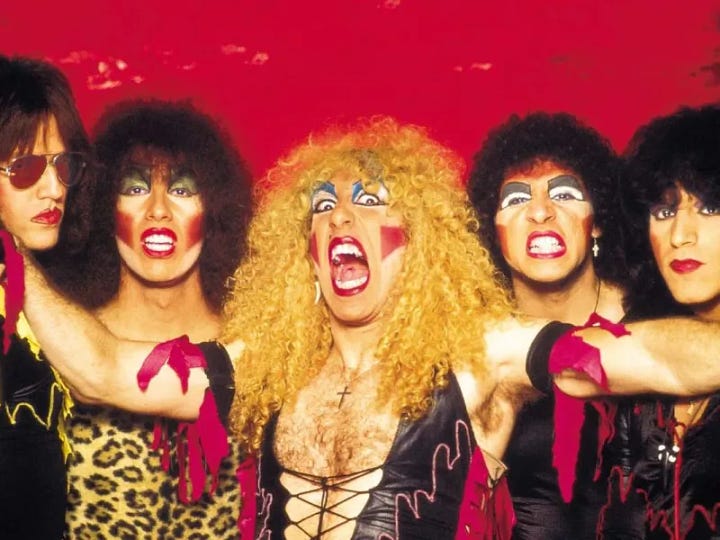

What about the sight of Mercury dressed in drag could inspire such a reaction from a cable music station that already regularly played videos of grown men with long hair, sporting eyeliner, wearing high-heeled boots, and, quite often, spackled in women’s make-up?

Undoubtedly, it was the fact that Queen made no attempt to embrace the sexual dissonance that hair metal bands typically did as they sang about sex, drugs, and drinking — you know, proper “masculine” activities — while otherwise embracing elements of drag.

There was no question that Twisted Sister or Mötley Crüe wanted to fornicate with women all night long whereas Queen’s members largely depicted themselves in the “I Want to Break Free” video as dull, sexless housewives — recreating parts from the popular ITV drama “Coronation Street” — and Mercury himself, as he blows kisses and winks playfully at the camera, wants you to know he’s up for it, mini-skirt and all, if you are. To make matters “worse”, the middle of the video sees Mercury in tights frolicking with a ballet troupe.

MTV’s message was clear in ’84 – men actually behaving like women was emasculating and morally wrong in America where men were men and women were something that no real man should actually want to be like. This was the way it had always been, it seemed.

Or was it?

After my grandparents died, I inherited a treasure trove of family photographs and records stretching back more than a century. Thousands of photos. It took me years to properly go through them and even begin to collate them into five family epochs: Taken When I Was a Teenager or Older (my only real memories), Taken When I Was a Young Child, Taken During My Father’s Life Before Me, Taken During My Grandparents’ Life Before My Father, and the all-mysterious Who the Fuck Are These People I’m Related to But Who All Died Before Even My Father Was Born?

As I tossed old photos, most of them in black and white, into the Taken During My Father’s Life Before Me pile, I found some of my favorite pics of my grandparents. They were surprisingly stylish people for their day; far more Bing Crosby and Rosemary Clooney than JC Penny super-shoppers. This always surprised me about my grandfather, in particular, as fashion was the very last thing I came to associate with him and his thriftily limited selection of blazers and “old man” hats later in life.

And then I found the ones of him dressed like a woman.

Not just my grandfather either, but a whole group of his friends. It’s clearly for a performance, almost certainly one at the local AMVETS’ Hall where he was a member. I’m guessing a fundraiser of some kind.

What’s important to observe, I think, is that nothing about these images, strange as they are to me, suggests my grandfather and his drinking buddies — all WWII veterans — are remotely uncomfortable with what they’re doing on this stage. There’s no attempt to hide it. They’re grinning for the camera, proud to have this moment commemorated for their children and grandchildren, such as me, to find the evidence.

There is a heartbreaking scene in the film All of Us Strangers (2023) in which a gay man named Adam gets to finally have a discussion with his father about his homosexuality and how he internalized his father’s unwittingly homophobic micro-aggressions.

“You’d tell me over and over again not to cross my legs like a woman,” he says.

The father seems surprised by this; he’d clearly never considered the damage he might’ve caused trying to program his boy into being something other than what he probably suspected he was.

“I still think about it every time I cross my legs,” Adam continues, his eyes trembling from the long-repressed trauma.

The thing about my grandfather is, I don’t want you to think I confuse those photographs of him in drag as some evidence that he and millions of other American men had boarded the Woke Train in World War II and never hopped off. Because he would tell me all the time to stop crossing my legs like I did as a child.

“Don’t cross your legs like that.”

“That’s how ladies cross their legs, kid.”

“Don’t do that.”

Very early on, I recognized the attempt by him, my own father, and the culture around me to control and shape me into a man’s man - which meant the least like a woman as possible. To allow anything remotely feminine to go unchecked could result in me catching the Gay, which would somehow be even worse.

For example, I could admire men, but not too much. Not unless they were athletes, of course; only then could I admire them and their physical power and ability all I wanted. I still recall a teenaged male neighbor popping into my parents’ house to use the toilet after a backyard whiffle ball game. He saw I had a poster of Harrison Ford on my wall, which he felt obligated to comment on. I needed more girls on display, he gently advised me.

The message was clear everywhere I turned - and any attempt to deviate remotely from the accepted norm was cause for communal concern and intervention.

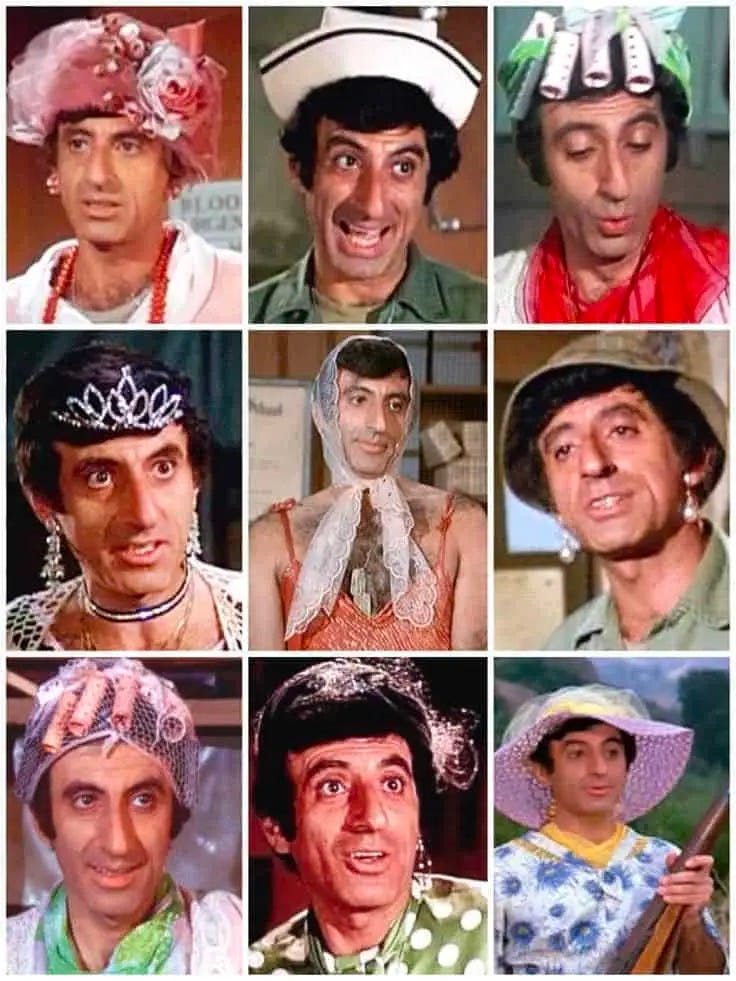

Growing up, I always wondered about the character of Corporal Maxwell Q. Klinger on the television series “M*A*S*H”. While he’s initially introduced as a cis man who wears dresses in an attempt to get an incredibly homophobic U.S. Army to kick him out, there was no getting around the fact that week in and week out, Klinger — played by Jamie Farr — dressed in women’s clothes even when other soldiers weren’t around. By Season 3, Klinger got married, via Ham radio, to his high school sweetheart while dressed in drag. By Season 5, he finally admitted to his commanding officer that he collected women’s clothing since before enlisting.

Most remarkable, no one in Klinger’s unit ever seemed to judge him, hurl slurs at him, or do anything other than treat him with respect. Yes, there were a few slip-ups by the writers’ room over the years, a handful of jokes that certainly didn’t age well — “Friends” is far more problematic, by comparison, I assure you — but, overall, it was and remains very obvious that judgment, disdain, or other bigotry was not a part of the relationships.

As for my grandfather, he loved “M*A*S*H”. It was his favorite TV series. Nothing about Klinger seemed to rattle him.

When the sitcom ended in 1983, after eleven seasons — an extraordinary feat given that it’s set during a three-year-long war — its final episode was watched by 106 million people in the States at a time when the country’s population was only 233.8 million people. And for all of my effort to find otherwise, no U.S. politicians denounced the “cross-dresser” amongst its central cast, complained about the commitment of “Hollywood libs” to corrupting children, or campaigned on doing away with such sick, deviant behavior.

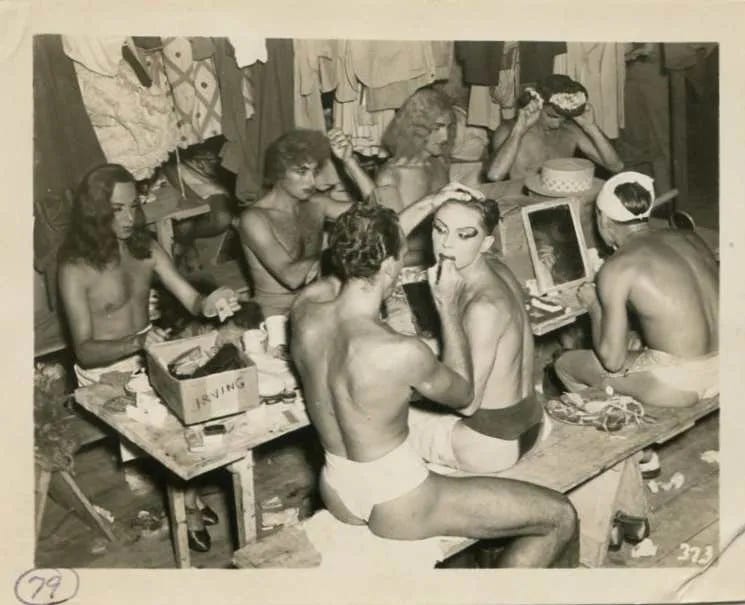

That might have something to do with the fact that many U.S. Congressmen and Senators in ’83 were World War II vets along with millions of other American men. All of them were accustomed to drag, which, as it turns out, was a formalized part of military service in World War II and an ongoing tradition in the U.S. military since 1880 until only recently.

My word choice is not reckless here: a formalized part of military service in World War II.

Even Ronald Reagan, the culture warrior Republican president of the U.S. at the time of “M*A*S*H’s” finale, starred in a Hollywood musical called This Is the Army (1943), an adaptation of Irving Berlin’s hit Broadway musical, that featured a performance by dozens of men dressed in drag – inspired by the drag shows that were commonplace across the Allied fronts and even within the Nazi’s ranks.

As it turns out, soldiers and sailors across the globe spent World War II mastering how to apply eyeliner, dancing in heels, and wondering if their dress made them look fat.

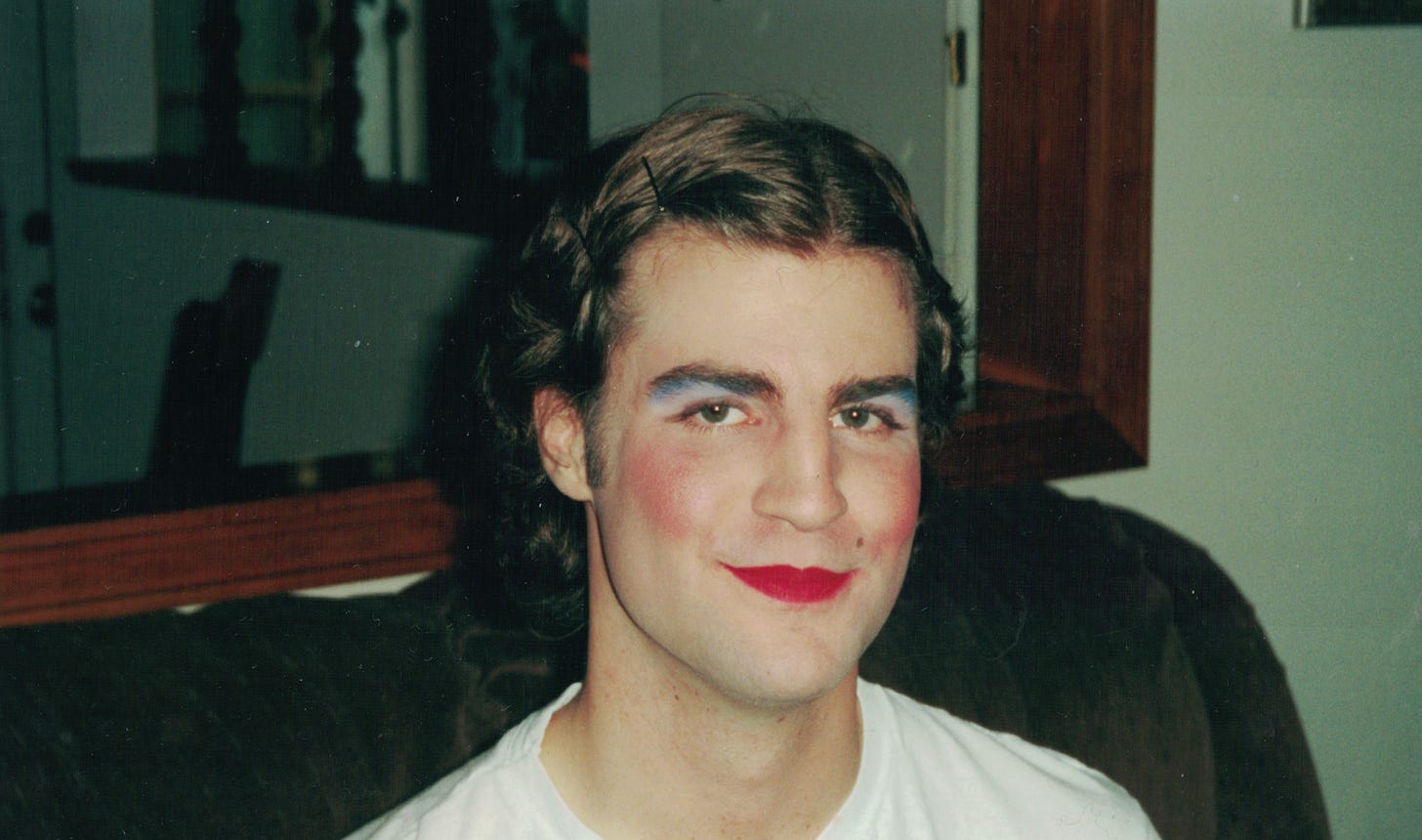

There is a memory I’d forgotten for so many years that it’s return to me about half a decade ago came as something of a relief. So much of my past, even as a young adult, has vanished on me.

In this memory, I am newly nineteen years old. It’s my birthday, in fact, and a group of friends has assembled in my parents’ garage to help me celebrate. Several of them keep checking their watches and beepers, concerned about something I assume is a surprise. Maybe a cake is arriving. Maybe someone is bringing a keg to sneak in when my parents’ aren’t looking.

Then, a car pulls up and parks on the street.

A woman slowly emerges from the dark, wearing a long coat, hobbling on heels that are either uncomfortable or she’s too drunk to wear.

I panic because the last thing I want is for my parents to find me in the garage with a stripper, but she makes it inside and my friends roll the door down behind her.

Except when her coat comes off, it becomes clear the person in black lingerie and stocking was what we would describe as assigned male at birth (AMAB) today. My friends hoot and holler, and I realize this has all been arranged as a kind of joke. I receive a lap dance from this person, who is, yes, very drunk. The stripper — who doesn’t actually strip, this not being part of the gag — seems tragic and sad to me. I want to hug them because they make money being laughed at by straight men who want to embarrass their straight friends.

“I’m sorry,” I whisper as this stranger grinds against me.

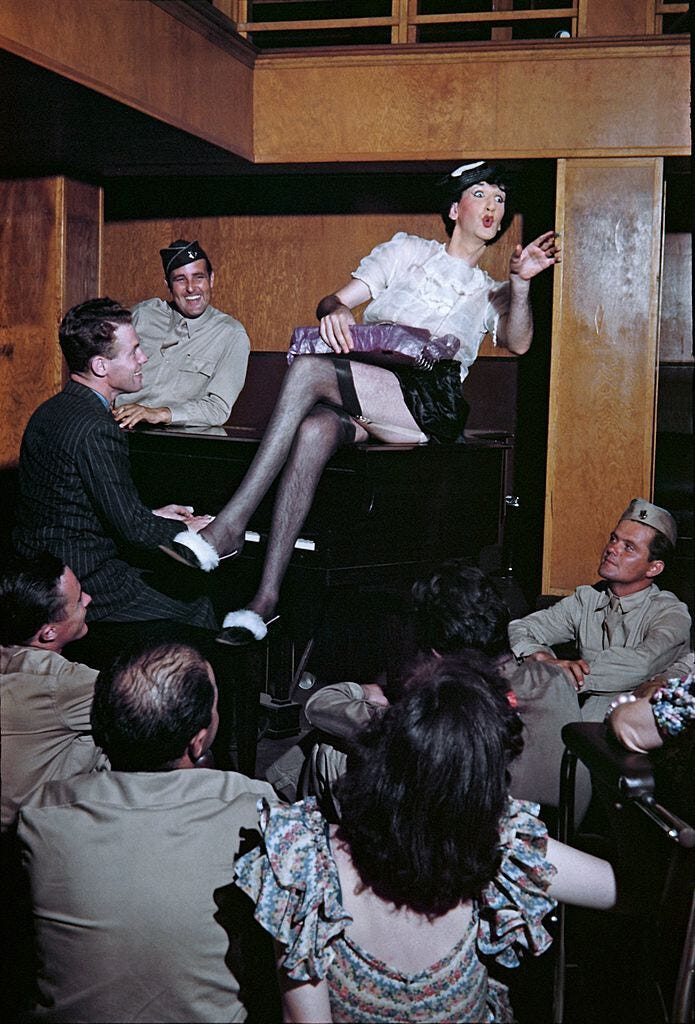

It’s important that it’s understood that nothing I’ve said so far about the U.S. military in World War II has been remotely exaggerated, especially how commonplace drag was to servicemen’s experience of the war. Female performers were rarely allowed near the fronts; members of the Women’s Army Corps weren’t permitted to take the stage for such risqué shows either, as it was judged — rightly so, knowing men (the sexual assault rate in an integrated military is horrifying) — they might not be safe in such environment.

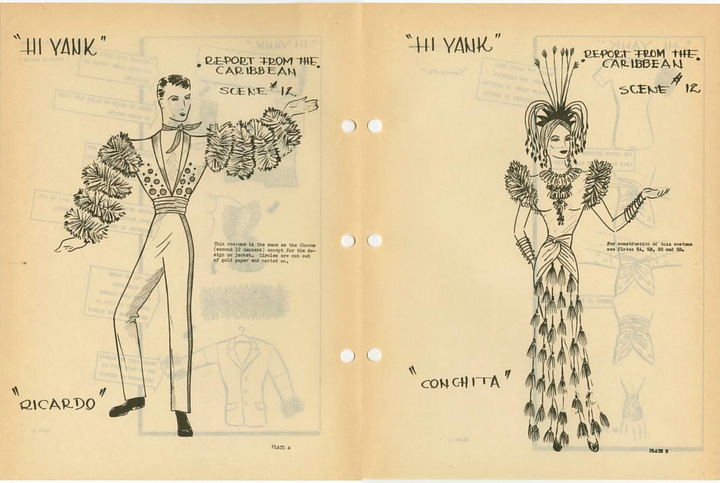

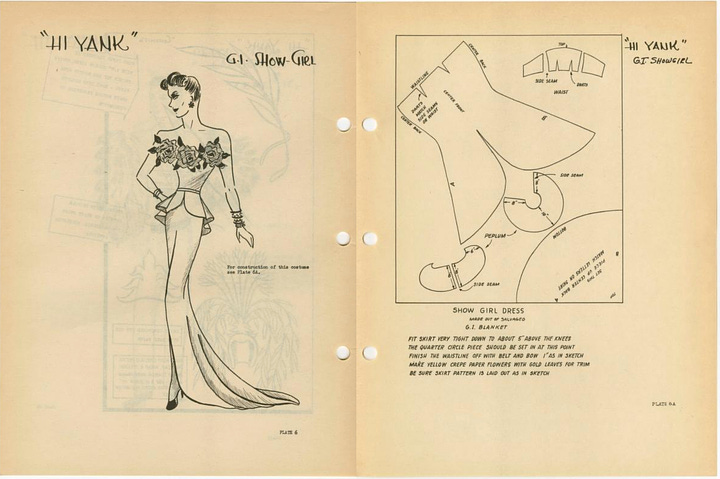

Instead, the role of showgirl was assigned to…men.

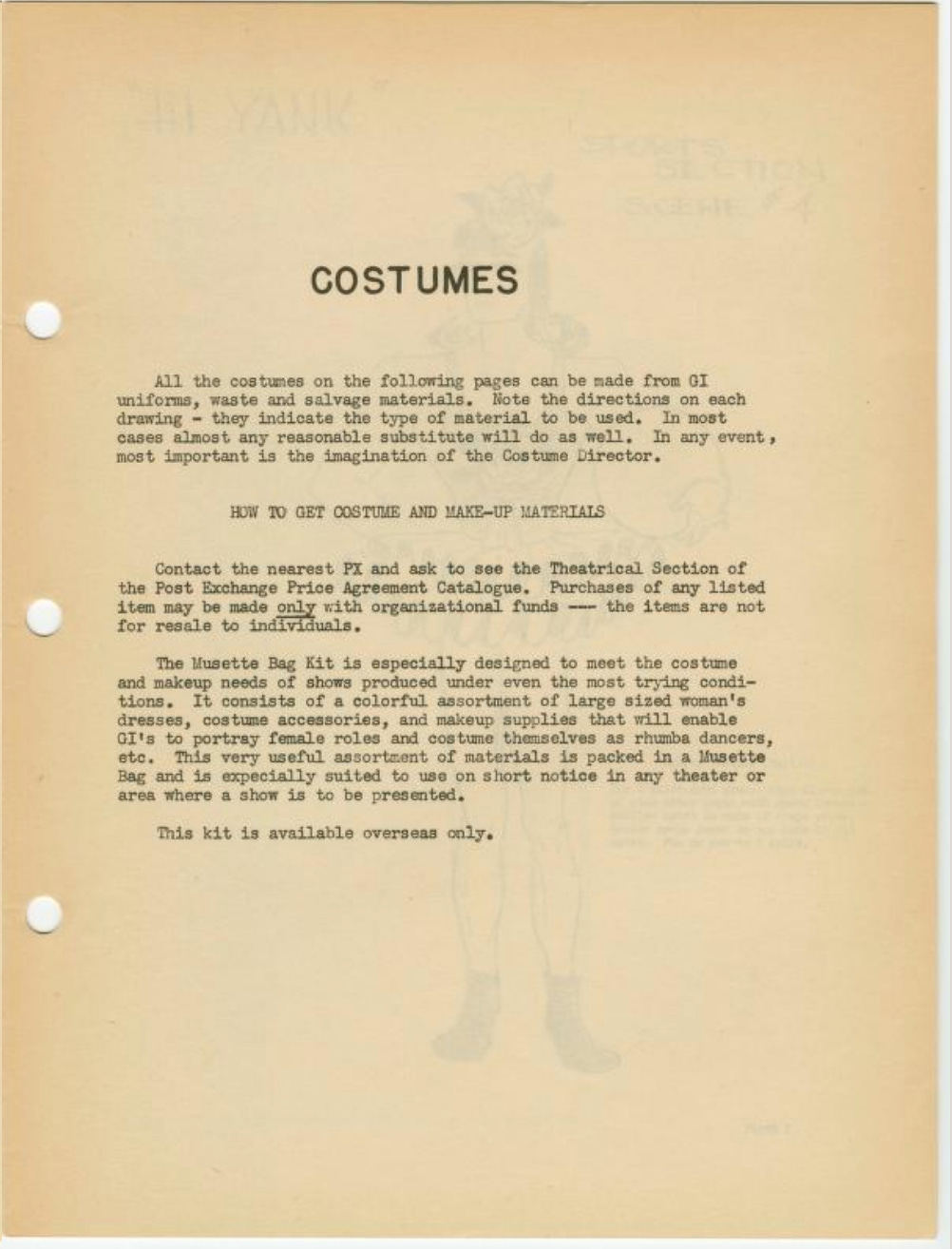

The Army Special Services created and distributed handbooks for just how to do this, too. They were called “Blueprint Specials”, and they basically told a unit everything it needed to know to put on an approved and pre-scripted soldier show. This included dress-making patterns and tips for material procurement, a problem for any extracurricular activity on the front or on naval ships. The Blueprint Specials weren’t content to let men stumble clumsily and unprepared onto stages dressed in women’s clothes. “Girly show” rules were laid out to ensure GIs looked appropriately feminine and sexy in their highly choreographed routines.

There were three types of drag performance that were commonplace in U.S. soldier shows during the World War II era thanks to the Blueprint Specials, which Irving Berlin would use when he created his Broadway musical This Is the Army – comedic routines, skilled “female” singers and dancers, and impersonators of the period’s biggest female stars. Basically, you’d show up for some bawdy humor, the Andrew Sisters, and Rita Hayworth. Men would hoot and cheer and, regardless of sexual orientation, I can assure you there was plenty of lusting.

Homosexuality was not permissible in an Allied military during World War II, and it was no less tolerated in American culture back home – a painful reality that wouldn’t begin to change until the Nineties almost a half-century later. But according to historians, these drag entertainers were not stigmatized or otherwise punished for their perceived or actual sexual identities. Instead, their performative femininity was celebrated as beautiful. When This Is the Army premiered on Broadway on July 4th, 1942, one reviewer even declared the performers in This Is the Army were some of the “most beautiful dames on Broadway.”

All this said, I think it’s important to flag that drag remains a complicated subject for trans women, amongst others, who can view the art form as only acceptable to some cishet men and women, especially cishet men, because it’s so often played for laughs. Because audiences might be laughing, in some manner, at the very idea that someone AMAB could ever want to actually be a woman — in other words, laughing at trans women’s very existence (consider the horrifying story of my nineteenth birthday party). Drag can also reinforce the bigoted notion that trans women are really “just men in dresses”, which is used to justify intolerance of and violence against them. In other words, this subject is obviously far more expansive than this essay alone can get at.

Here’s another memory of mine for you. In it, it’s the Halloween season in Michigan. I’m twenty-five. Friends have invited me to a “pimps and hoes” costume party, which, embarrassingly for all involved, are still commonplace across America. I’ve been to two, and that was enough for me. The one in question, the second, provokes an act of rebellion from me.

There are going to be several people present who have bothered me with their casual sexism and racism over the years, so I decide to confront them over it not with words, but with — let’s call it — performance art. I’m also just curious how I would feel about the whole thing.

With the help of two female friends, I visit thrift stores, find a dress and wig, and put on make-up for the first time since my cousin dressed me up like her doll when I was four. Heels are a bridge too far without more time to practice, so I settle on flats. To confuse others who might recognize my eyes, I initially wear sunglasses to further obscure my identity.

What happens next will shape me and how I view women and their experiences in this world for the rest of my life – not to mention the experiences of everyone across the queer spectrum.

As guests arrive, I stroll up to the men and say hello just as if I would if dressed as a man. I try to hug them, too; maybe slip an arm around their shoulders. In almost every case, I am shoved away the moment the man realizes I’m “a dude”. Not just shoved, but often violently shoved with verbal disgust. And then, when I reveal it’s me, someone they know, they promptly apologize and, more tellingly, laugh as if we were all in on some great joke together.

Fun fact: the only person I do this to who doesn’t have this reaction and who enjoys having me hang on him throughout the evening is a cishet male Marine. Nothing I can do makes him uncomfortable. As for all the other cishet men present…well, as I said, it’s a lesson I’ve never forgotten.

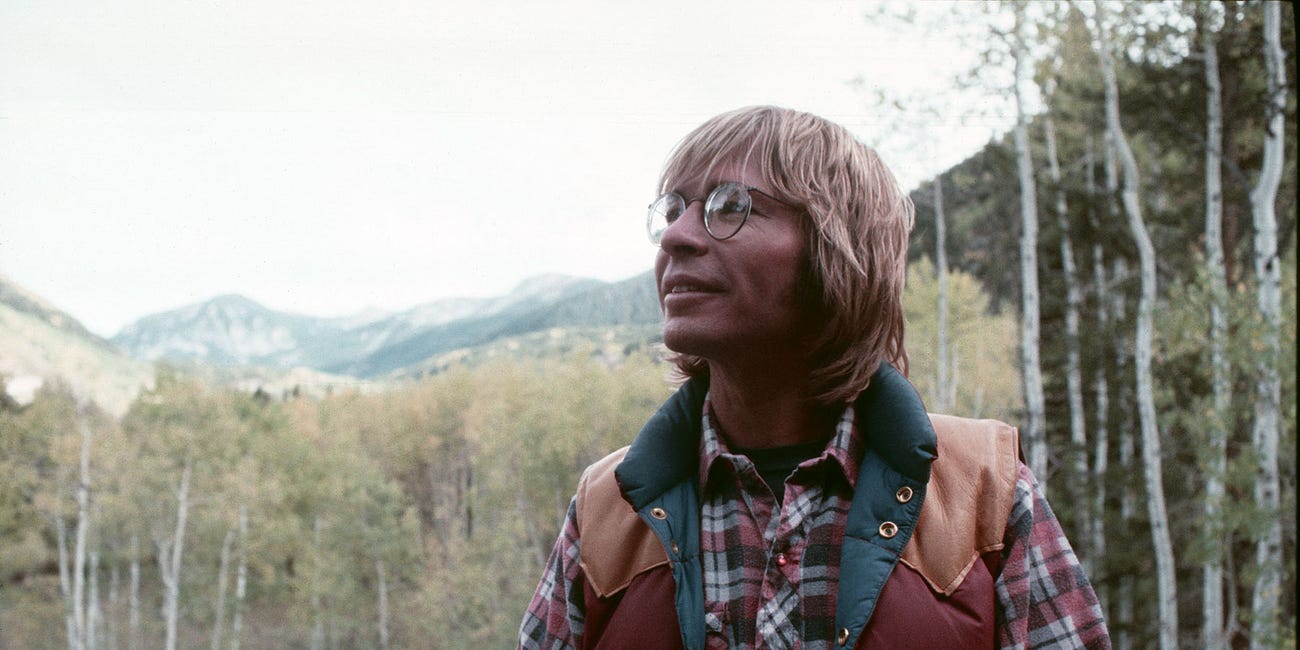

When I was twenty, I was gifted a VHS copy of Queen: Live at Wembley by an aunt who also appreciated the band’s genius. Performed over multiple nights in front of a total audience of over 400,000 — 150,000 in the first two nights alone — I was immediately struck by how men seemed to make up the majority of the crowd and how all of them were screaming for Freddie Mercury as he strutted and pranced and ran and danced across the stage.

There were not enough gay men in London at the time to fill that stadium over multiple nights. This is not a teeming crowd of homosexuals who showed up to cry out for Mercury, is my point. It’s a crowd that cishet men make up a disproportionate percentage of, and who, like the rest of the straight world at the time, apparently had no idea Mercury wasn’t one of them.

I try to imagine how this is possible, but straight people had been doing this for decades with famous entertainers by the time Mercury joined the conversation. Cognitive dissonance is a special talent human beings possess. It allows us to navigate so many incredibly complicated, incomprehensible aspects of life — from grief, to the violence of war, to the meaning of our existences — but apparently has never been one of my strongest suits. Because at ten years old, at a time when American talk shows were fixated on the alleged social danger of homosexuals, inspiring my parents to declare things such as, “God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve!” I wasn’t the least bit confused about how fabulously queer this Englishman was.

He was one of my first heroes in the art world. His operatic voice cried out emotional truths I was still grappling with and some I still am. In many ways, Queen taught me to think in terms of music. My life wouldn’t be the same without either of them.

The instinct to label the video for “I Want to Break Free” as emasculating might still be socially appropriate to some sub-sections of men around the world, but, once you get past your pre-programmed misogyny, I find it profoundly masculine – and feminist. These are men, all but one of them cishet, embracing ugly tropes about female housewives and horny barmaids, tired characters in a sexist world, and they do so fearlessly. They don’t give a shit about you and what you think. It’s all kinds of glorious.

In so many ways, the United States and the world has changed since MTV initially refused to air “I Want to Break Free”, but it’s also regressed in many others. Consider how drag, a tradition commonplace in the U.S. military for close to a century and a half, was banned on military bases in 2023 because of pressure from Republican politicians looking to score cheap points with bigoted voters. Across the country, drag shows and performers are now targeted as both debased and dangerous to children. The situation only gets worse when we begin to discuss trans people’s rights, which are being eroded in the U.S. and countless other countries around the globe – driven by a kind of nonsensical, frothing paranoia jump-started by Far Right politicians, religious hatemongers, and a batshit crazy and increasingly malignant Scottish author.

It's a cycle of hate that we all seem trapped by, doomed to repeat it because so many have been culturally programmed to fall for it even as we simultaneously participate in and celebrate a world — on our screens, in our communities, and even on the battlefield —where the opposite appears to be true. We all just want to break free from whatever we feel trapped by, of course. We all just want to live our lives on our own terms. Maybe that’s why Queen’s song endures as an anthem of both self-liberation and political liberation - it promises tomorrow won’t always be like this.

Find additional reading/viewing material and sources by scrolling down.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Additional reading/viewing material and sources regarding drag, the U.S. military and World War II, and trasn representation in the media can be found here (WARNING: please be aware that some of these links involve images of soldiers in Black face):

Watch the film adaptation of Irving Berlin’s This Is the Army on YouTube for free.

Watch a fantastic mini-documentary on “soldier shows” and drag in the U.S. military during WWII here.

Read “GIs as Dolls: Uncovering the Hidden Histories of Drag Entertainment During Wartime” here.

Read the “Hi, Yank!”, a U.S. Army blueprint special soldier show here.

Find more international drag photos from World War II here.

Read more about the Pentagon banning drag shows in 2023 here.

It wasn’t just the Allied Forces putting on drag shows. The Nazis did it, too. Read about that here.

My friend screenwriter and author Tilly Bridges offered helpful thoughts on this essay. I’d encourage you to read her essays on trans life and trans representation in media here.

This is such a beautifully written and thought-provoking piece. Your comparison of the Queen video with the conflicting appearance and accepted misogyny of hair metal bands certainly speaks of the times but I agree that the current reactionary movement really is frightening. In my children I see a generation so much more tolerant and accepting of difference and I find it frustrating that such a level of resistance in other quarters still exists to just allowing people to be who they want to be.

Cole, I want to apologise. Recently you posted a thoughtful note about Klinger which (I now realise) was based on research you did for this piece. And I thoughtlessly replied in “Well, actually” mode. I was wrong!

I also want to thank you, because it sparked a thoroughly enjoyable M*A*S*H rewatch.