We're All Made of Horrible, Beautiful Scars

Australian rocker Nick Cave, Native American activist/poet John Trudell, and a 14th-century Japanese shogun have thoughts about how to put ourselves back together through art

IT'S JULY 14TH, 2015. At 3:40 in the afternoon in the South of England, a fifteen-year-old boy sends a selfie to a friend using Snapchat. In the foreground of the photograph is his youthful, smiling face; in the background, waving grass and a blue sky smudged by bright white clouds. An old windmill rises from a gentle slope, the true subject of this image.

Van Gogh might’ve stopped to paint this moment in time.

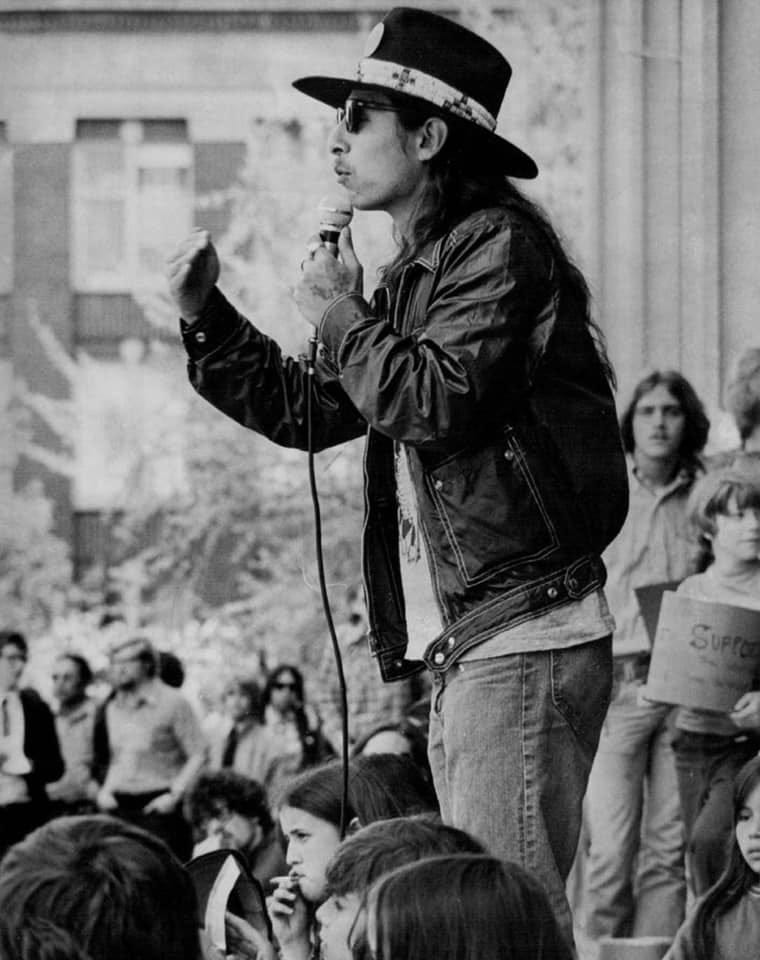

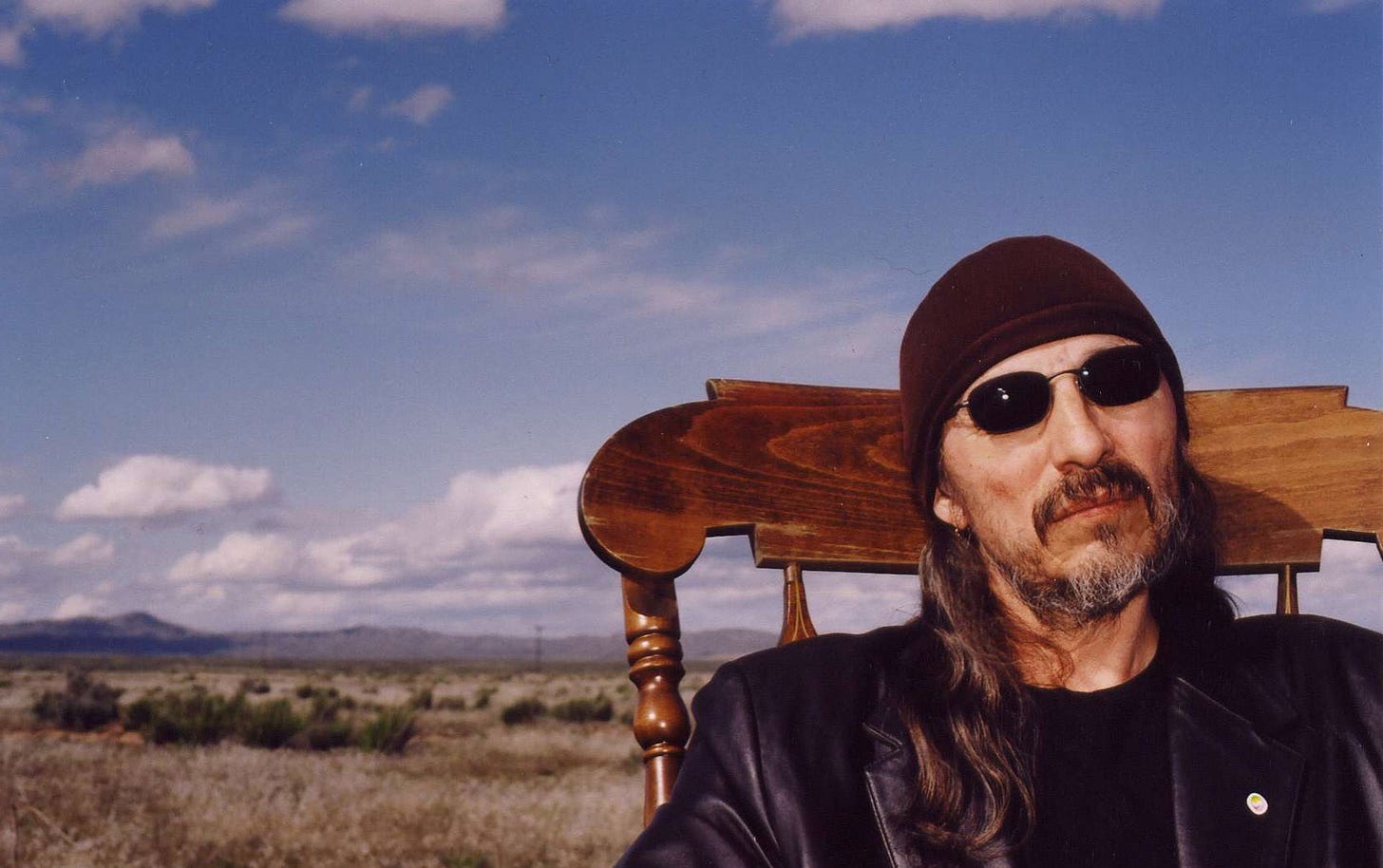

IT’S FEBRUARY 11TH, 1979. Native American activist John Trudell stands on the steps of the FBI building in Washington, D.C. and addresses a crowd despite the many warnings he’s been given against speaking out. But this guy was the spokesperson for the United Indians of All Tribes’ occupation of Alcatraz Island a decade earlier. He doesn’t know how to keep his mouth shut when it comes to his people’s rights, which is why the FBI has a 17,000-page dossier on him - one of the largest ever compiled. The U.S. government is on an organized crusade of terror against Indians, he tells those gathered.

Then, he burns an American flag.

Not far from the bucolic windmill he had photographed just two hours earlier, the fifteen-year-old boy spills from a cliff. He hangs in the air for a moment, his tether to this world already beginning to snap. Then, he crashes into the underpass of Ovingdean Gap in Brighton.

He dies later that evening at Royal Sussex County Hospital.

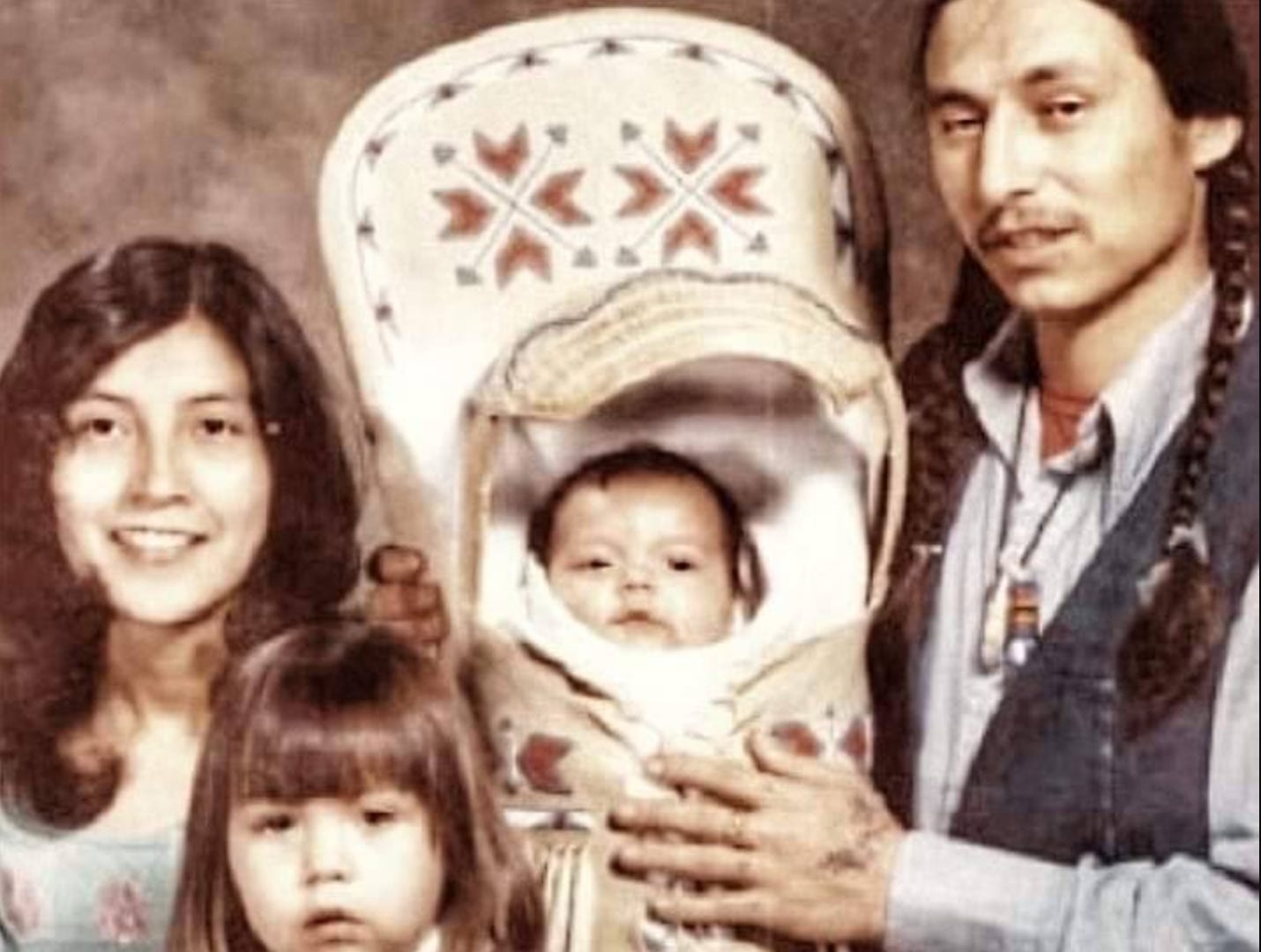

John Trudell is still in D.C. when it happens - which means it’s 3:30 a.m. on February 12th, 1979, when the screaming starts halfway across America. His wife Tina — an activist like him — is asleep in her father’s house on the Shoshone-Paiute Reservation of Duck Valley, which straddles the Nevada and Idaho borders. She’s home with her parents and her three young children, Sunshine, Ricarda, and Eli. The blaze kills all of them except her father, who escapes and goes for help. The FBI never investigates what Trudell insists was arson, an attempt to silence him and his family, murder.

Tina was pregnant with their fourth child.

IT'S JANUARY 2ND, 2024. My wife wonders, “I don’t know how anyone could go on after something like that,” when I tell her the story about John Trudell’s family. She says this to me quite a lot, her voice distant as her thoughts drift to the possibility of ever losing her own children.

“I don’t know how anyone could go on after something like that.”

IT'S THE 14TH CENTURY. Ashikaga Yoshimitsu beholds the broken pieces of his favorite tea bowl. It was a unique thing of singular, irreplaceable beauty and the Japanese Shogun, unwilling to accept its loss, sends it to China to be repaired. When the tea bowl returns, its pieces have been fixed together with metal staples, not dissimilar to how Frankenstein’s monster will one day be interpreted on celluloid. This kind of staple job is common at this time in China and even as far away as Europe, but the results unsettle the Shogun. His favorite tea bowl can serve its function again, but it’s aesthetically disagreeable to his particular gaze. Ill-favored. Ugly.

The crestfallen Shogun commands a solution to his dilemma be found.

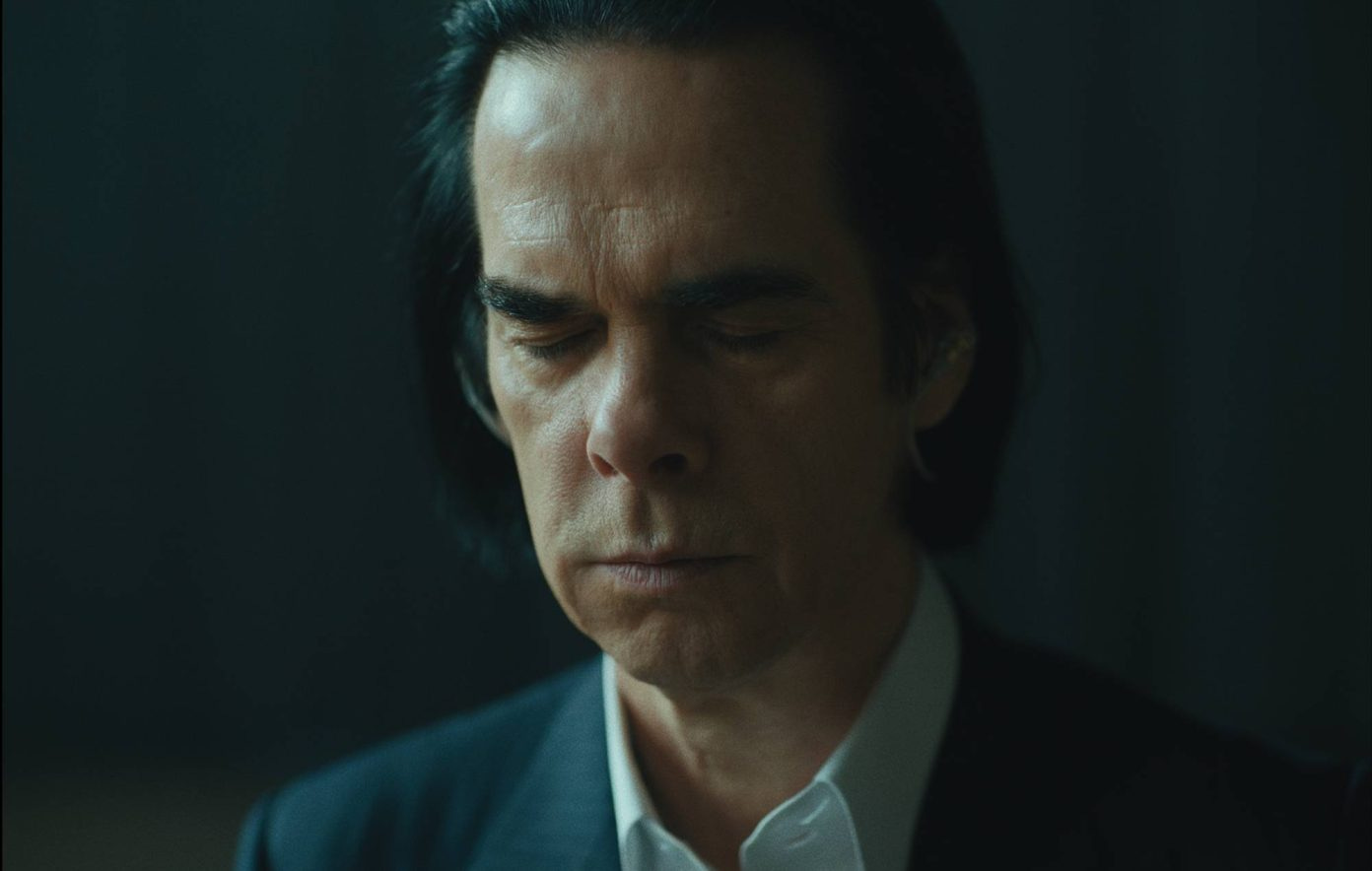

IT'S FEBRUARY 2021. The pandemic has been raging for close to a year now. Millions have died by this point. My father wasn’t one of them, but he died all the same last week. I’m currently lying on my couch early in the morning, listening to Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ double album GHOSTEEN as I stare at the back of my eyelids, trying to make sense of what’s happened. I had no idea how much I would ultimately come to need these two pieces of pressed vinyl at this exact moment.

Cave recorded GHOSTEEN in 2019, four years after his fifteen-year-old son Arthur fell to his death not far from where their family lived at the time. It’s a sublime experience, letting its atmospheric, often meditative symphony of synthesizers, piano, and other electronica wash over and through you. The rocker’s voice seems almost a whisper compared to so much of what he’s recorded. It’s wounded and mournful and desperate and pleading and just confused. The lyrics it sings dramatize a kind of protracted waking nightmare, of lost faith and the search for it, of lost hope and reluctant acceptance, of…something broken being put back together.

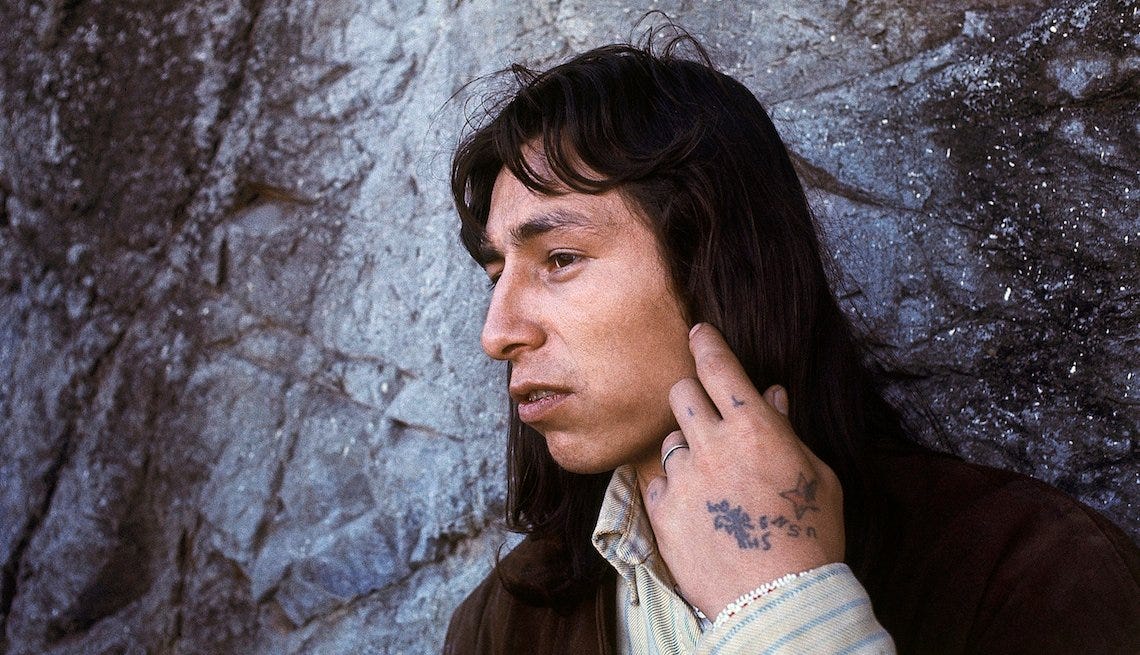

IT'S JULY 1979. John Trudell is in Vancouver, six months after the loss of his entire family, to request political asylum from the Canadian government. He wakes in the middle of the night, his dead wife Tina in his thoughts, working through his hands, and scribbles down his first lines. He knows others would call them poetry, but he calls them his “hanging on lines”. They are Tina’s parting gift to him, he believes, and he knows he must follow them wherever they take him.

The Shogun’s tea bowl is again returned to him, the ugly metal staples removed. Instead, its many pieces, its broken and sharp edges, have been glued back together — for lack of better words — with a lacquer. But no attempt has been made to hide the repair. In fact, powdered gold has been mixed into the lacquer so that the tea bowl now appears as if a delta of gold rivers crawl across its entire surface. Thin, snaking veins of gold, so that the damage to the tea bowl has become part of its aesthetic. Part of its story. The tea bowl will never be what it was again, but the Shogun knows none of us ever are. We break over and over.

He is pleased.

The final track of GHOSTEEN is called “Hollywood”, but in many ways it’s a story in halves like the double album itself. In the first, the narrator — whom we know is Nick Cave — stares into the abyss. Or maybe it’s the futility of what he has left. He and his wife have tried to run from it “all the way to Malibu (Cave and Arthur’s mother had fled Brighton to the Pacific Coast after the boy’s death), maybe he’s even tried to run from her inside their marriage, and now all that’s left is waiting for the inevitable. “And I’m just waiting now for my time to come/And we hide in our wounds,” he sings, repeating these sentiments in different ways, over and over again. “And I know my time will come one day soon/I’m waiting for peace to come.”

But then, the first half of the song ends with a final allusion to Arthur’s death: “The kid drops his bucket and spade/And climbs into the sun.”

The second half of the song — more specifically, its final third — provides a response to Cave’s grief through a Buddhist parable about a mother named Kisa Gotami whose baby has died. Devastated, desperate to save her child, Kisa climbs a mountain to speak with the Buddha. The Buddha tells her not to cry yet, suggesting there is still hope. “Go to each house and collect a mustard seed/But only from a house where no one’s died.”

IT'S 1982. John Trudell puts his poetry to music for the first time, spoken word lyrics backed by rock and traditional Native American instrumentation and singing. A year later, he releases his first album, TRIBAL VOICE, produced by Jackson Browne. Bob Dylan calls it the album of the year.

Once, Trudell’s voice made the FBI quake. Now, it breaks hearts and moves minds from stages and radio speakers. Art has become his protest, but really his way of communicating with and trying to make some sense of his past, his people’s past, their pain.

Kintsugi, or “golden joiner”, is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with lacquer that’s been mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. It treats breakage — but, really, repair — as part of the history of an object. No attempt is made to disguise the “scar”, so to say. The cracks and repairs are, instead, part of the life of the object.

The art of Kintsugi can be related to the Japanese philosophy of mushin — or “no mind” — which encompasses concepts of non-attachment, acceptance of change, and fate as aspects of human life.

Kisa went to each house in the village

My baby’s getting sicker, poor Kisa cried

But Kisa never collected one mustard seed

Because in every house someone had died

Kisa sat down in the old village square

She hugged her baby and cried and cried

She said everybody is always losing somebody

Then walked into the forest and buried her child

Everybody’s losing someone

Everybody’s losing someone

It’s a long way to find peace of mind, peace of mind

It’s a long way to find peace of mind, peace of mind

And I’m just waiting now for my time to come

And I’m just waiting now for peace to come

For peace to come

In the first half of “Hollywood”, Nick Cave sings of waiting for his “time to come”, for his “peace to come”, too. But these lyrics suggest resignation, surrender, something almost suicidal.

In the second half, a different kind of resolution is proposed. Not hope as Kisa Gotami clung to. But an accord with grief. The day when Cave can live with it, when it becomes a part of him — a different him — rather than the thing that beats him.

IT’S 1994. John Trudell releases “After All These Years” fifteen years after his wife’s death. He still breaks down into tears when discussing her and their children in interviews.

After all these years

The last time I saw you

Was only

A moment away

As always

I reach for your touch

Only to find

I’m teardrops behind

IT’S AUGUST 2020. Half a year into the pandemic, journalist Seán O’Hagan gets on the phone with Nick Cave for the first of several conversations that will become the book FAITH, HOPE AND CARNAGE. It’s been half a decade since Cave’s son Arthur fell to his death.

O’Hagan asks his friend if he’s completely abandoned the idea of the traditional narrative song that he spent most of his career recording, preferring instead the fractured style of songwriting he’s more recently embraced. Cave admits he’s been thinking about this a lot lately, stuck on “big, classic, and grand themes” of “By the Time I Get to Phoenix”, “Wichita Lineman”, “Galveston”, and “Always on My Mind” amongst others. O’Hagan suggests these songs feel from “another time, another world” now, but Cave isn’t so sure about that:

Yes, but the world I inhabit now, at this point in time, does seem very different to when we made GHOSTEEN. It feels more put back together. There is a shape to it. It may not be the same shape as it once was in fact, it is barely recognizable - but it does, at times, feel like life has returned to a more orderly narrative, rather than something fractured and smashed apart.

I don't take that feeling for granted, Seán. We should never underestimate that sense of being in the groove of life, of moving from one situation to another with the wind at your back, of being purposeful and valuable, of life having some semblance of order. It's really something, that feeling, made all the more because you know how transitory and easily broken it is. It seems profound to me, life is mostly spent putting ourselves back together. But hopefully in new and interesting ways. For me, that is what the creative process is, for sure it is the act of retelling the story of our lives so that it makes sense. That's why I love those old songs - they gather up the broken pieces of a life and organize them into something that is coherent and meaningful and true. I could listen to them all day.

The art of kintsugi is also related to the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which is a worldview concerned with the acceptance of transience, imperfection, and the beauty found in simplicity. More, wabi-sabi is also an appreciation of both natural objects and the forces of nature that remind us that nothing remains the same forever.

IT’S 2001. John Trudell releases “My Heart Doesn’t Hurt Anymore”, a song that feels like the end of a long and terrible journey. The hanging on lines have finally brought him some kind of resolution. Acceptance. Ugly and sad wisdom.

My heart doesn't hurt anymore

But my soul does, maybe

That's what souls are for, to

Take the hurt the heart can't take

The heart can't take

“The act of retelling the story of our lives so that it makes sense.”

But really, the act of putting ourselves back together through our art. The breakages, the scars, the hanging on lines on full display. Because nothing remains the same forever.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

This is perhaps the most profound and moving writing I’ve read in years. The way you weave the stories together in a slow reveal demonstrates masterful design of craft. Knowing that this story was generated within you at a point of massive heartbreak over the loss of your father adds a depth of soul that brought me to tears. Thank you for making me think and feel and realize so much on a rainy Saturday morning at a point of my life in which I have so much to be grateful.

Beautiful writing and storytelling! I love the serendipity between Nick Cave and John Trudell that you display here. Great work. :)