How John Denver Helped Me Find My Way Back Home

Music can connect us to each other, through grief and sometimes even across time and space

It is 2016. My mother has just died some 2,000 miles away from where I live in Los Angeles. There is an immediate sense of coming untethered that accompanies this once unfathomable loss. A sense of connection to something older than I am suddenly snapping, something that remains a mystery to me despite all of my attempts to reveal and understand it. My mother is gone, and a part of me has gone with her, a part of me I don’t know how to make contact with again.

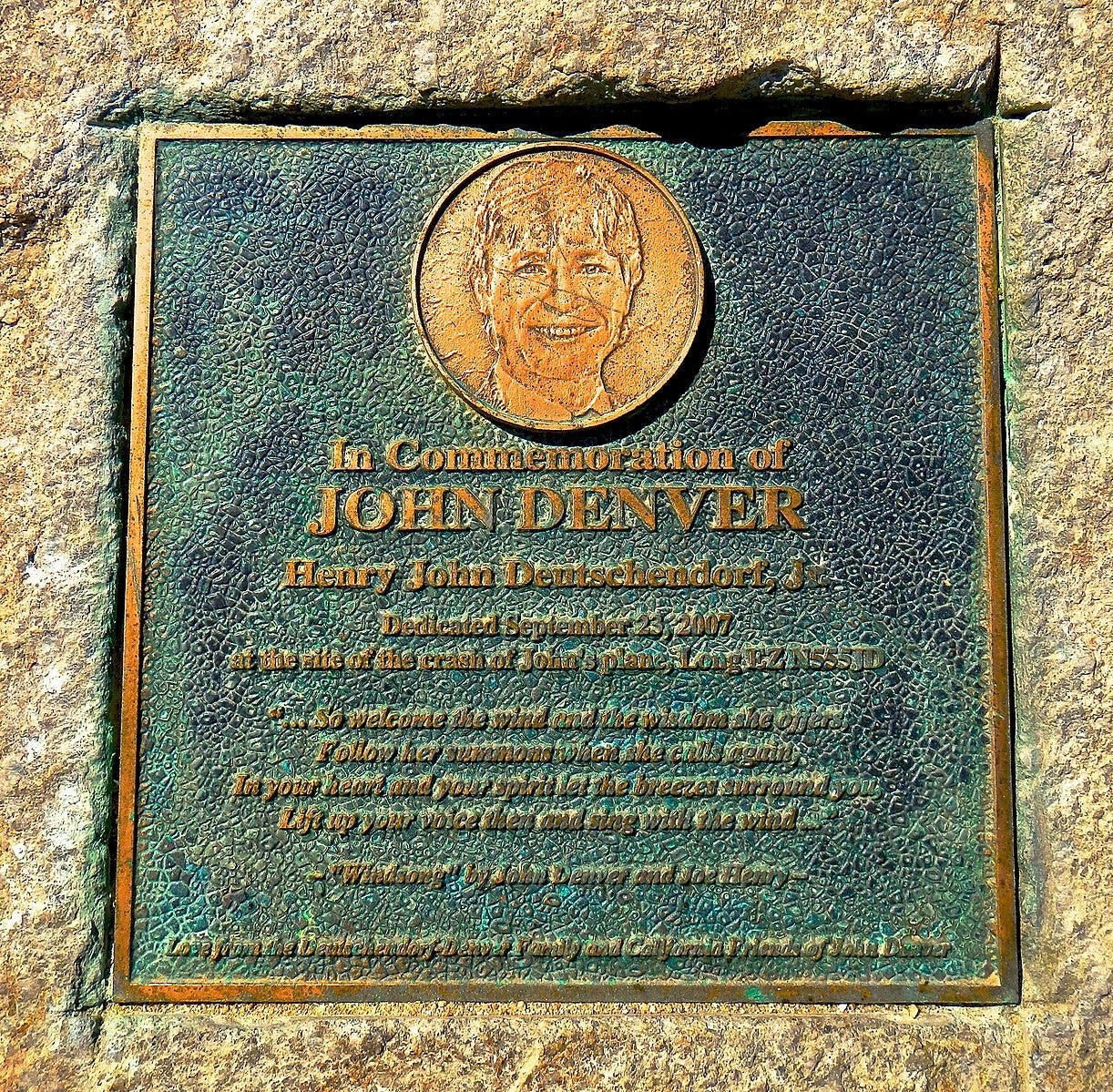

It is 1997. John Denver, the musician who gave the world “Rocky Mountain High” and inspired a multi-generational debate about whether he is country music or pop music, is about to die and he knows it. Of course, I am not there with him as he plummets toward the unforgiving surface of Monterey Bay, though there would’ve been room for me in the empty rear seat of the homebuilt tandem two-seater plane he is piloting. Poor design choices, an ill-conceived decision not to refuel the last time he touched down at the airport, and probably over-confidence in his abilities as a pilot have conspired to doom Denver. This isn’t my story, but it is a part of my story, and years later I will wonder if he thought about his children in these final moments and if his children still struggle, despite the cushion of time, with the sudden and deafening silence that replaced their relationship.

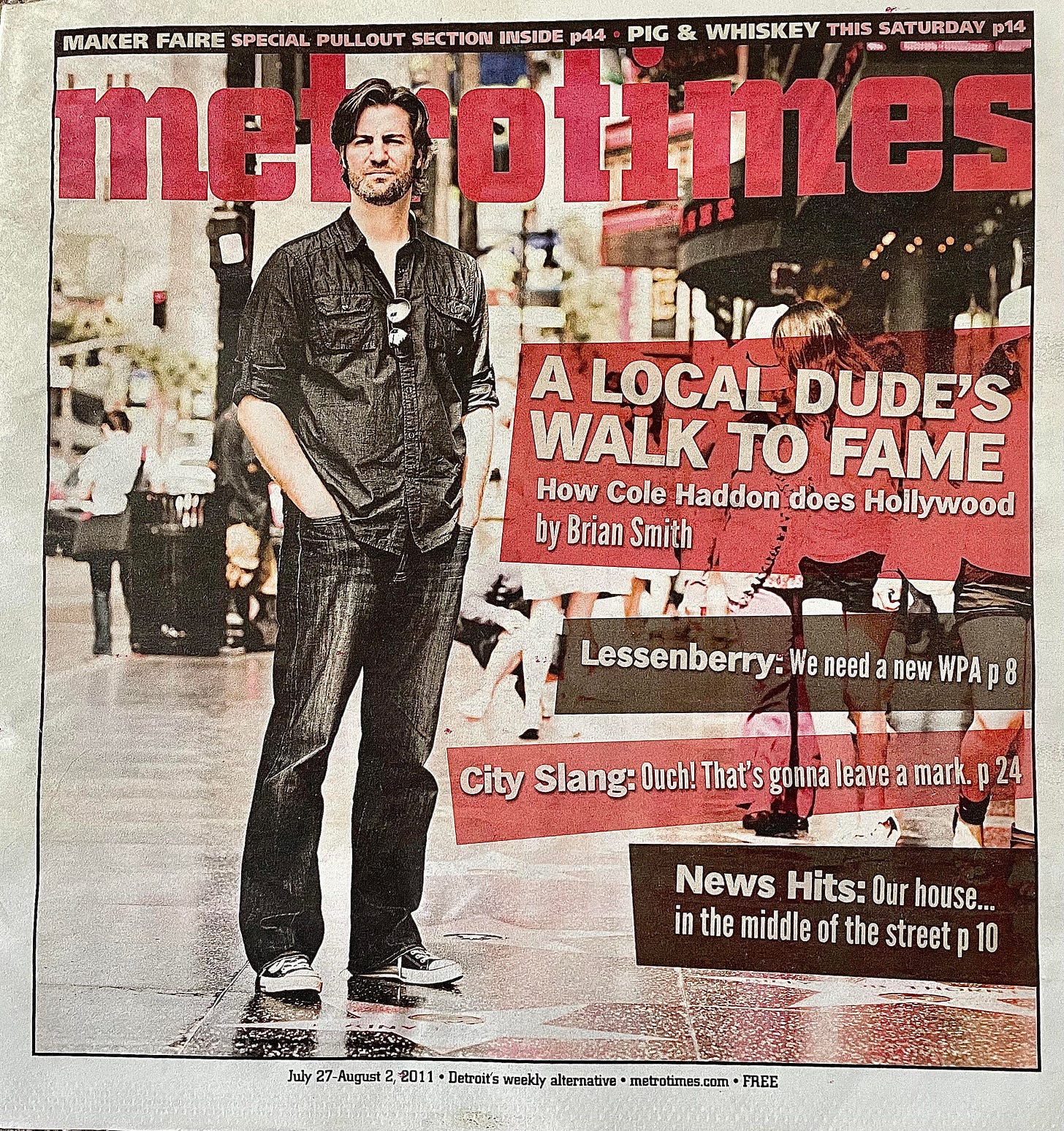

It is 2004. I am living in the city of my birth, Detroit, with aspirations of becoming a paid member of the diverse taxonomy of writers. One strategy to accomplish this goal is to cold-email the local alternative newsweekly’s music editor and ask him if he’ll employ me as a freelancer — even though I have no credible experience and I’m wholly unqualified to discuss music given twenty-eight years of life with only passing interest in it. I include in this email a largely fraudulent resumé that states my name is Cole Haddon and that I am a published journalist. Neither is true. The music writing sample I submit along with this fictional identity is real, though, and he promptly replies with three sentences: “I love your name. Great work. Let’s talk.”

Within a year, I am working so consistently as a music journalist that I decide to fulfill my lifelong dream of moving to Hollywood to pursue a career in screenwriting.

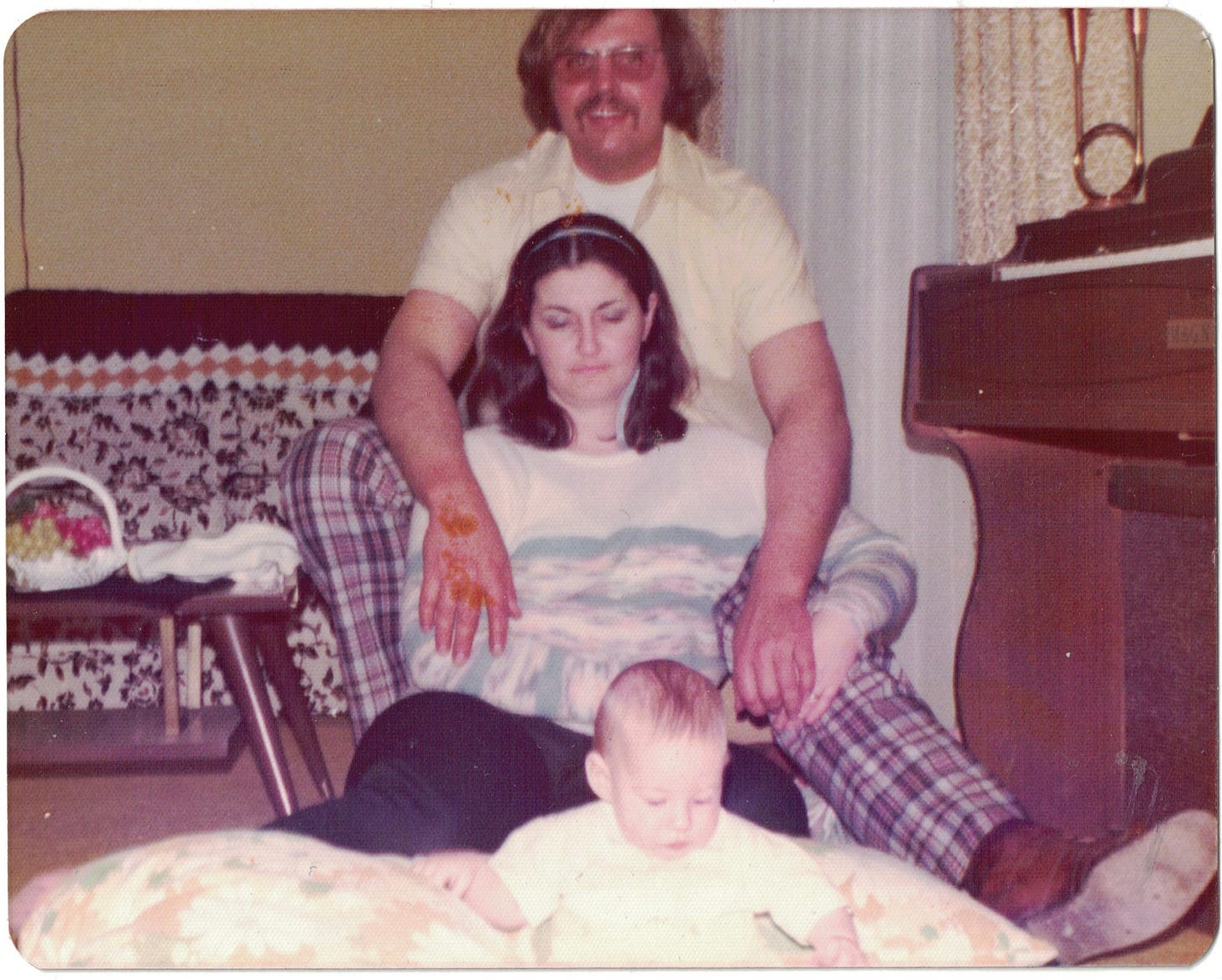

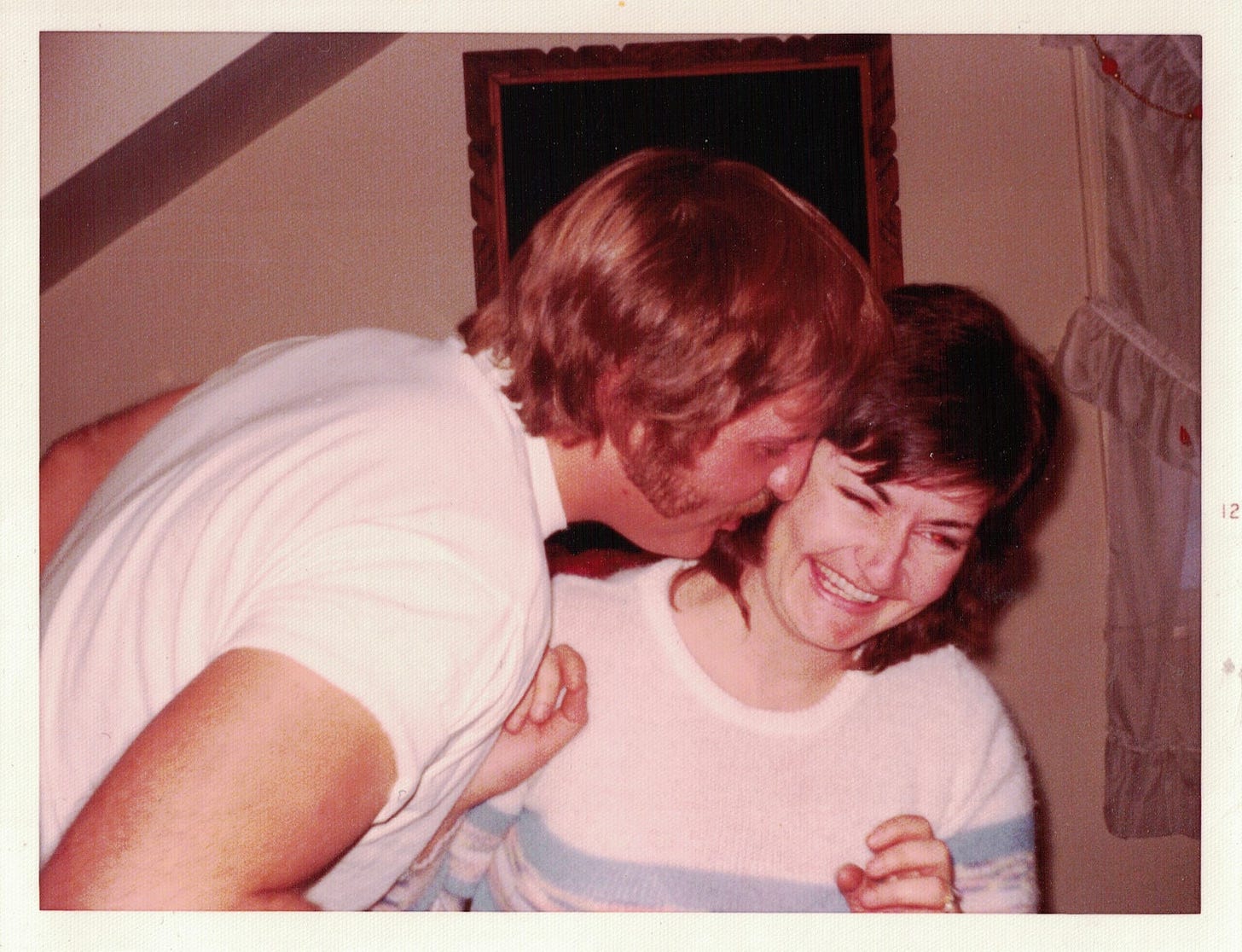

It is 2016. I am standing in a Michigan funeral home, trying to hide how my chin is shaking because I somehow never internalized my mother’s life lesson that it is okay for men to cry. She was an Australian immigrant who came to America to marry my father, who is sitting in the funeral home tonight despite the fact that the two of them divorced more than a decade earlier. My sister has assembled several large boards of photographs that summarize and celebrate our mother’s life, and in one of these my father is also sitting down, our mother on the floor in front of him and me, maybe four or five months old — which places this event in late-1976 — propped up by pillows between her legs. We are in the living room of his parent’s house, his long, thick arms are hanging over her shoulders, and there is love between them, loud and clear to me, and the sight of it — non-existent in any of my memories of them — sends me fleeing to a dark room to bawl.

I forget about the photo as soon as I leave the funeral home later that night.

It is 2006. My first full year in L.A. has passed, most of it spent feverishly writing articles from my bedroom in a Silver Lake Craftsman. At the moment, I’m on the phone, interviewing Nashville-born singer-songwriter Cary Brothers for the first time; he’s currently enjoying some success after his song “Blue Eyes” made a splash on the GARDEN STATE soundtrack. When you telephonically interview people, it’s always difficult to tell if you’re making a real connection. But Cary doesn’t bullshit. He’s just cool. More, he makes you feel cool.

It is 2012. My wife gives me my first record player for my birthday. It is a portable one, a mass-produced piece of shit that never works wholly right, but she presents it to me with several vintage albums she found at a street festival and I remember yet again how much I love this woman. I begin to add to the sparse collection she gifted me immediately — everything from David Bowie to Bing Crosby to Al Green to Nina Simone — and I must buy a record stand by the end of the year to hold them all. Vinyl unexpectedly awakens something in me, which I attribute to the tangible nature of an album in your hands rather than stored in your mobile phone or suspended in the digital ether, the warm, intimate sound one produces, the way each one accrues scars just like people do and those scars add to the music in some mysterious way.

It is 2007. Or maybe 2010, or 2002, or 2013, or what feels like every other time I’ve spoken to my mother since I moved away from home. We talk two to three times a week, but it’s always spent grasping at more. We both wish to have a closer relationship, but neither of us seem capable of it. She inevitably brings up CMT (Country Music Television) or some new country singer she likes or how cruelly “they’re treating Taylor Swift”. I don’t know what she’s talking about. I tune it out. I tell her I don’t like country music anymore, which is only mostly true. I just don’t want to talk about it with her, not like when I was much younger and we could get lost in CMT for hours together. I don’t want to discuss the things she loves anymore, mostly because I am an asshole.

I don’t know why I can’t try harder.

It is 2014. My wife and I have just bought our first home in Los Angeles, made possible in part by my success as a screenwriter, and one of our first purchases as homeowners is being carried into our living room by two men. It is one of the only pieces of décor I required to feel comfortable here, a vintage record player cabinet, not quite as old as the one I had in my imagination, the kind my grandparents used to own, but it will do the trick and immediately fills me with a childlike thrill. A rack of albums is rolled into position beside it once the delivery men are gone, and from it I select the first one to spin in our new home. It’s AL GREEN’S GREATEST HITS, and the irony is not lost on me that a person who couldn’t tell the difference between Motown Records and Chess Records ten years earlier now cannot stop talking about music and assembles playlists to accompany every film and TV project he develops. I am perpetually intimidated by the deep knowledge of music history demonstrated by so many I know, especially the musicians I call friends, but I am patient. I’m okay spending the next several decades catching up.

It is 2017. I am now living in Southeast London with my pregnant wife and our three-year-old son. I have become a list aficionado — some might even say a fiend — for complicated enumerations, and decide it is time to impart upon my son my passion for curating and cataloguing life’s delights, accomplishments, and many remaining goals. I begin to choose three vinyl albums a month to play for him, discussing each with him in detail even if he will not remember who is who or what I’m talking about because, as mentioned, he’s only three.

My wife finds it ironic that someone who possessed so little personal passion for music when we first met eleven years earlier now feels it so necessary to provide a music education to our child.

It is 2014. My firstborn is three days old, and I am slow-dancing with him in my living room, his body pressed against my chest and my cheek against the crown of his bald head. Johnny Mathis’s first greatest hits album is spinning inside my record player cabinet, an album I bought from the Fairfax Flea Market on a whim after my mother told me she ceaselessly listened to Mathis growing up in Australia, a factoid that surprised me as I had never heard her discuss anything other than her obsession with country music as a child. I sing along with the crooner’s smooth, soothing voice — “chances arrre you think III’m in love with youuu” — serenading my beautiful boy as I will do endlessly until he is too big to dance with him like this.

Over the next several months, I will struggle with a new and consuming fear that I will somehow lose this child, that accident or disease could steal him from me and his mother, or, almost as worrisome, that he will grow up and find himself as disinterested in me as I am in my parents. With this new fear comes the realization that the opportunity to repair my relationship with my mother is dwindling by the day and will soon vanish all-together, but, despite this, I don’t imagine she will be dead in two years and my son and his yet-to-be-born brother will grow up with no memories of her.

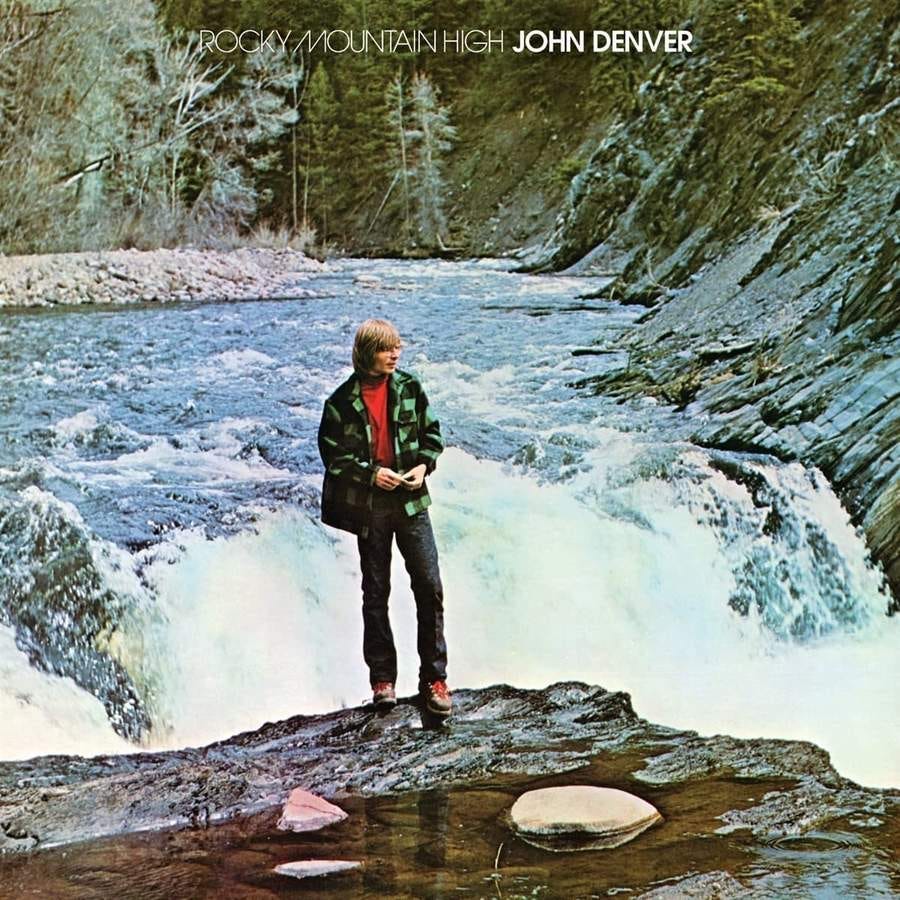

It is early 2018. My wife suggests she needs less soul and rock-and-roll in our musical diet and, instead, more pop. Even country music will do, just to mix things up, she says. I remember she loved when her father played John Denver for her as a little girl, and so I head to eBay and order a copy of Denver’s album ROCKY MOUNTAIN HIGH (1972) as one of my monthly vinyl plays for our son.

Denver has been dead for more than twenty years at this point, and I haven’t listened to his music in easily as long. I have no memory of it in my childhood either, outside of the major singles that I only vaguely recollect because they bubble up in pop-culture here and there and almost always with a degree of cynicism. In his lifetime, he was often derided as “Mr. Sunshine” or with descriptions like “Mickey Mouse pop” and, in the years since his death, no significant reconsideration of his work has transpired to correct this assessment of his deep song catalogue.

My reaction to Denver’s music is…considerably less dismissive. After the needles lifts from ROCKY MOUNTAIN HIGH’s Side 2, I find myself gobsmacked by his poetry and the soaring, spiritual quality of his songs. They are like hymns of love and nature, and I later try to explain this to my second-born son, not even three months old yet, as we dance together to the series of suites to the seasons as experienced in the Rocky Mountains that almost entirely comprise one side of the album.

Denver experienced his beloved Rockies the same way, I soon discover. In his autobiography and numerous interviews, he used language that touched upon the metaphysical to describe them; how the air there seems to “purify your lungs”, how there is a “solemn, cathedral-like darkness” in its forests, “how in nature all things, large and small, [are] interwoven”.

In 1985, Denver testified against censorship in Congress because his song “Rocky Mountain High” had been banned in some places in the 70s for the alleged drug reference in its title and lyrics. Denver argued that those who labeled his song as such “had never experienced the elation, celebration of life, or the joy in living that one feels when he observes something as wondrous as the Perseid meteor shower on a moonless, cloudless night, when there are so many stars that you have a shadow from the starlight”.

Less than a year from now, my wife and I will decide to move our family from London to the Oxfordshire countryside because we miss the connection to nature that Denver sings about.

It is early 2019. Cary Brothers, whom I have become good friends since I first interviewed him thirteen years earlier, releases a haunting cover of John Denver’s “Take Me Home, Country Roads”. It is the rare cover that both reinvents the original in a way you cannot stop listening to while simultaneously celebrating the original. His father died a few years back and I am still struggling to deal with the death of my mother despite the passage of two years.

The music video Cary releases for the single speaks to these severed connections, that yearning need to return to something that feels like home but is unreachable now. As a consequence, I cannot stop thinking about his cover of this song.

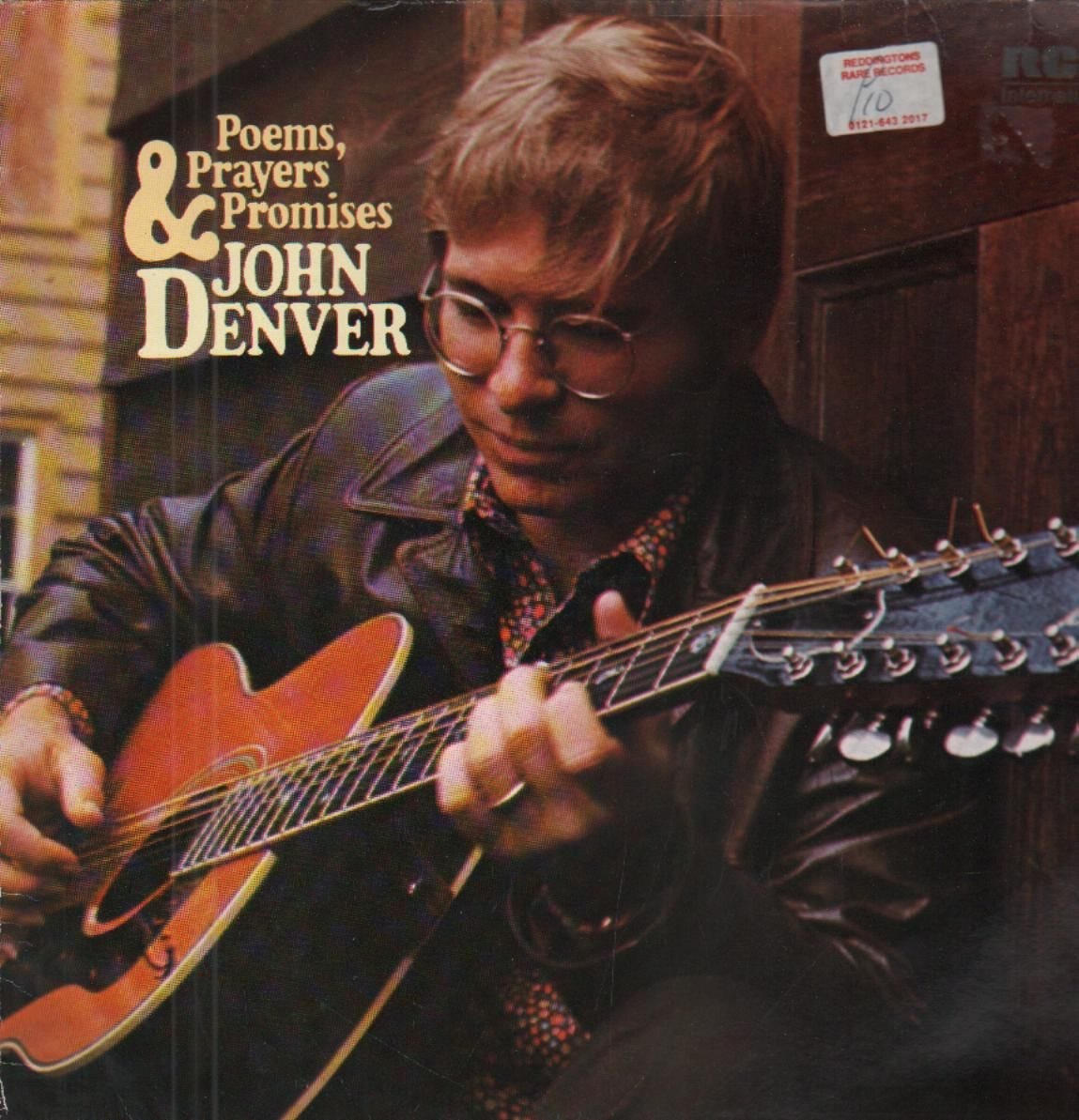

I head to eBay, and immediately order Denver’s POEMS, PRAYERS AND PROMISES (1971) where the song made its first appearance nearly half a century earlier. It arrives a week later, the second Denver album in my vinyl collection.

It is late 2018. My friend Nicole Taylor’s debut feature film, a decade-long passion project called WILD ROSE, premieres at the BFI Festival in London. Her script is about a troubled Glaswegian single mother of two children (Jessie Buckley) who relentlessly pursues her dream of becoming a country music singer even when it puts her family at risk. Mostly, it is an ode to the transformative power of country music set in a culture where country doesn’t seem to have a place.

Afterwards, Nicole asks me what I think about her film. I am numb from the experience, and I give a very technical answer that no doubt is interpreted as a polite brush-off of her hard work. I feel guilty, and the next day I write her a lengthy email about my own mother’s youthful dreams of becoming a country music singer in distant Australia, a world that felt to her as far away from Nashville as Nashville is for the central character of WILD ROSE, and how my own complicated relationship with my mother drove a wedge between me and country music. Nicole’s film violently kicked that wedge out from where it had become so tenaciously fixed. The result, I tell her, is an exacerbation of much of the guilt I feel over aspects of my relationship with my now-dead mother, but also the release of memories I think I had blocked out. Specifically, memories of country music, how much I loved it, and how much I loved listening to and sharing it with my mother. In doing so, she had inadvertently shown me a way back to my mother in some small, unexpected, but powerful way.

It is early 2019. Thanks to Cary Brothers’ cover of “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” I have found myself unable to stop listening to John Denver’s music. Denver’s celebration of nature speaks to me more and more as time passes, especially now that my family has moved the countryside of Oxfordshire. His elevation of nature as a great connector to something older than any of us feels spiritual, even divine, and it vibrates in my cells at a frequency I increasingly crave with age. I feel better listening to it, similar to what I felt when I once believed in sky gods.

I bring Denver up to my wife, probably trying to articulate some of this strange reaction I am having to his songs. She tells me for the first time she thought I loved his music so much because my mother loved him so much. I tell her this isn’t true, that I can’t remember my mother ever mentioning Denver when she was alive. In fact, my only clear memory of Denver with relation to my parents is their reaction to his death that Wikipedia informs me was in 1997. In this memory, they are only passingly upset, as they were when another singer from their youth, Ricky Nelson, died twelve years earlier than Denver in another small plane crash.

It is mid-2019. I am packing up my home office in London, in preparation for my family’s move to Oxfordshire’s countryside, and find the beat-up box of valuable family artifacts that follows me around wherever I move in the world in place of the deeper relationship with my parents I never achieved in life. These artifacts include items such as the passport my mother used when she emigrated to America, a newspaper clipping announcing her first marriage, photos of her family in Australia that I collected during my many trips there, and, a more recent addition, photos I brought home from her memorial.

I don’t remember how these photos made it to London with me. I was so discombobulated after the memorial, I assume they made it into my possession, traveled back to Los Angeles with me, and eventually made the move to the United Kingdom with my family, but I can say none of this with any certitude.

I begin to leaf through the snapshots of a past, marveling at how young and happy my mother looks in so many of them. I do not remember her as a happy person. She certainly wasn’t in the end when a lifetime of traumas often brought her to tears in the midst of conversations that were only connected to them in her mind. The past had become ever-present for her, the present increasingly a place where there was no time left to build new, happier memories. Our conversations had grown disjointed because of this, often difficult to emotionally track as moments in her long life sometimes collided with each other like atoms with equally disastrous results. Einstein argued time was an illusion, after all, which makes more and more sense as we experience it over a lifetime. But despite the gulag my mother had imprisoned herself in the last years of her life, mistakenly she could protect herself there against a tortured past, I was now confronted by numerous photos of her with my father, both of them happy in the first years of their marriage. I had sometimes been told this was the case, even by them, but with a total lack of more than circumstantial evidence to corroborate such claims.

One photo in particular strikes me. I remember it from the memorial. It is the one of my father and mother and me, four or five-months old, that sent me fleeing before I broke down into stinging tears. Despite the more than two years that have passed since my mother died, I cry again seeing this image of a family still full of hope and the promise of joy to come.

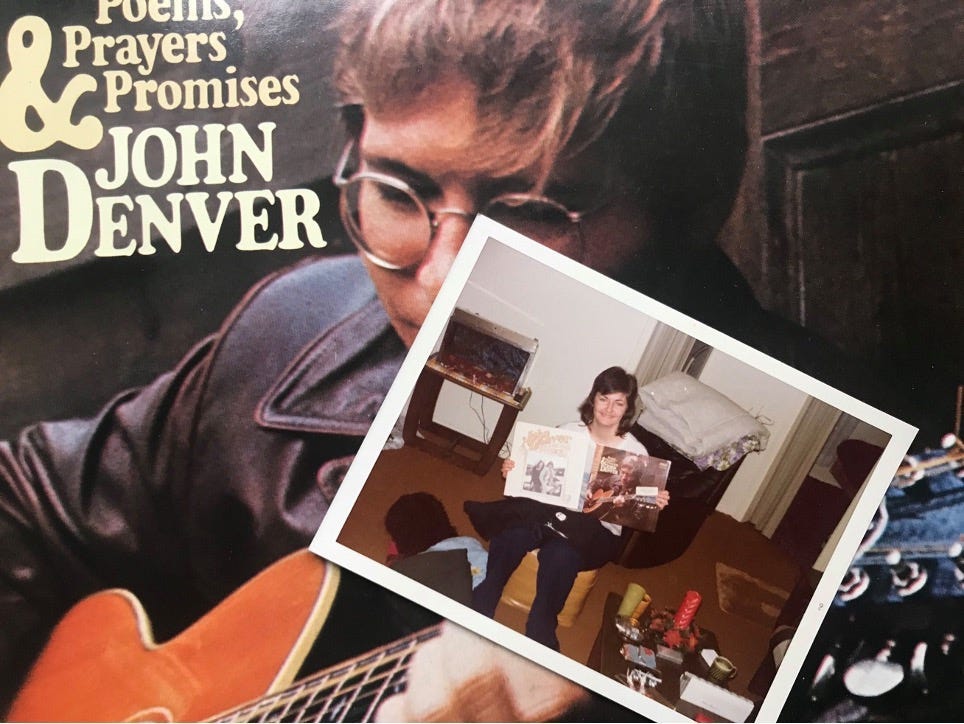

The next photo in the pile is of my mother on what I presume is her birthday. In her hands are two albums. I almost miss who they are by as I move onto the next photo in the stack. I stop, go back. My breath catches in my throat, my hands tremble.

The two albums are from John Denver: POEMS, PRAYERS AND PROMISES and BACK HOME AGAIN (1974).

My father has just given these to her. What I am looking at is one of those photos you take to commemorate the receipt of gifts, though I don’t know why any of us bother. Maybe for this reason here, because in one sudden instant, thousands of events since that moment in 1976 when the photo was taken, events good and bad, joyous and excruciating and everything in between, collapse like a star and then detonate into something like perfect understanding for me more than four decades later.

I do not believe in gods or higher powers or karma or anything that smacks of the Force.

But I do believe humanity is more interconnected than we take the time to recognize. Past, present, and future play like songs on a seemingly random mix tape we often cannot appreciate until it’s too late. Then, the tape snaps inside the cassette, with the abruptness of death, and friends and loved ones and even a great album can glue the loose, twisted pieces of broken tape back together for us and show us the way home again just as surely as a familiar country road.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy these other ones from 5AM StoryTalk:

Wow. Another fantastic, poignant time-travelling piece. Thank you for sharing so much of yourself on here.

Cary Brothers is masterful when he covers any song. He truly makes it his own. And John Denver is a national treasure. He died far too young. I’ll always believe that great music can get us through any hardship, grief, or loneliness, as well as joy. It’s powerful when we recognize that