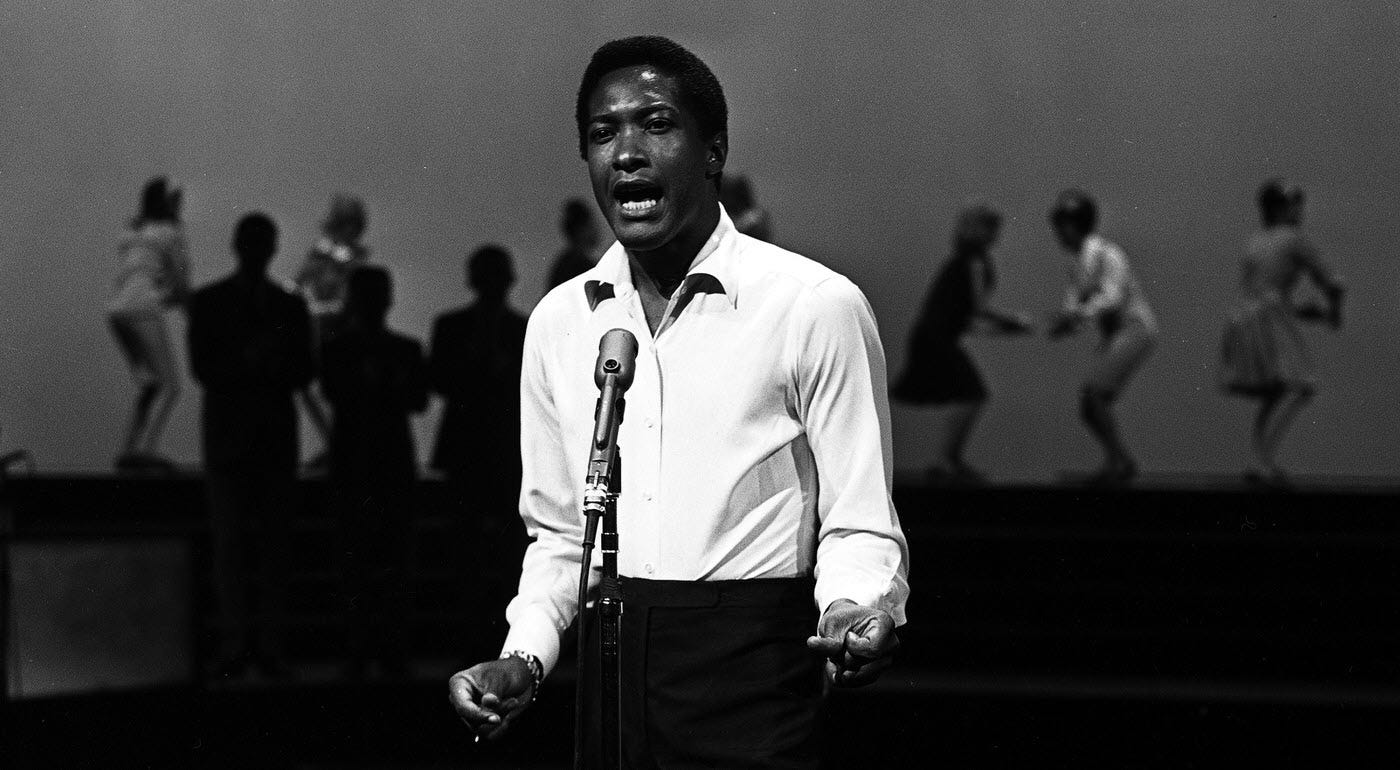

Sam Cooke's 'A Change Is Gonna Come' and the Audacity of Hope

Sixty years after the iconic song's release, its message couldn't feel more naive...or more necessary

OCTOBER 8, 1963

“They’ll kill you,” Barbara Cooke pleads with her husband inside the lobby of the Shreveport, Louisiana Holiday Inn North.

The hotel clerk watches them from his side of the counter, something — maybe smugness, maybe disdain, probably both — tugging at the corner of her lips. She’s just informed a group of four Black people there are no vacancies even though a reservation was made in advance. Barbara’s husband is frothing; his brother Charles and a friend from Chicago, S.R. Crane, have started shouting, too.

"They ain't gonna kill me because I'm Sam Cooke!” Barbara’s husband snaps.

The clerk, confident that none of them would ever dream of laying a hand on a white woman, not in the South at least, not since what was done to that Till boy in the next state over, crosses her arms across her chest.

“No,” Barbara whispers, “to them you're just another…you know."

Moments later, the group peels out of the Holiday Inn’s driveway, hurling insults at the desk clerk, and leaning into the car’s horn that screams violently like Cooke struggles not to do every single day of his life.

JULY 27, 2004

I’m watching as State Senator Barack Obama, the Illinois Democratic candidate for the United States Senate, takes the stage at the Democratic Convention at the FleetCenter (now the TD Garden) in Boston, Massachusetts. A few months earlier, during the Illinois primary, he’d scored an unexpected landslide victory and made himself an instantaneous rising star within his party. His choice as the convention’s keynote address is only a surprising choice if you’re not aware many were already talking about his presidential future.

In the end, that's what this election is about. Do we participate in a politics of cynicism or a politics of hope? [Presidential candidate] John Kerry calls on us to hope. [Vice-Presidential candidate] John Edwards calls on us to hope. I'm not talking about blind optimism here — the almost willful ignorance that thinks unemployment will go away if we just don't talk about it, or the health care crisis will solve itself if we just ignore it. That's not what I'm talking about, I'm talking about something more substantial. It's the hope of slaves sitting around a fire singing freedom songs; the hope of immigrants setting out for distant shores; the hope of a young naval lieutenant bravely patrolling the Mekong Delta; the hope of a millworker's son who dares to defy the odds; the hope of a skinny kid with a funny name who believes that America has a place for him, too. Hope in the face of difficulty. Hope in the face of uncertainty. The audacity of hope.

For a moment, it seems like everything is going to change. The ghouls who led us into two wars, one on manufactured evidence of weapons of mass destruction, will be banished to the annals of history as a foolish lapse in judgement after the eight years of general progress that accompanied President Bill Clinton’s two terms in the White House.

But Kerry and Edwards lose the election four months later. So much for hope.

OCTOBER 8, 1963 - ONE HOUR LATER

The car carrying Sam Cooke and his wife pulls into the Castle Motel on Sprague Street in Downtown Shreveport, and the singer — famous for radio hits such as “You Send Me”, “Wonderful World”, and “Twistin’ the Night Away” — sees the police cars waiting for them. The group is arrested for disturbing the peace and later released on bonds of $102 apiece.

Cooke has experienced many degradations in his life and on the road, but this one stings more than most. It takes up residence inside his mind where it refuses to dislodge itself. Something has to change…but that change feels so far away right now.

NOVEMBER 4, 2008

Barack Obama stands on stage in Grant Park in his home city of Chicago. 240,000 people have gathered to hear the newly elected president of the United States speak. This all seemed unthinkable eight years ago when George W. Bush stole the 2000 election with the U.S. Supreme Court’s help. I am sitting in Los Angeles, watching this all happen, and I’m crying like everyone else around me. Within days, I will begin to realize that other liberals and the national media are suddenly convinced racism has been solved simply because Americans elected a Black man to the White House.

CHRISTMASTIME, 1963

Sam Cooke wakes from a dream, trembling. His wife Barbara implores him to go back to sleep, but he can’t. Something is speaking to him, something that scares him. He has to find a pen.

The words flow out of his hand and race across the page. Maybe this is what it felt like when the Gospels were written, the voice of God in the Apostles’ ears. “I was born by a river…” it begins.

NOVEMBER 8, 2016

I’m listening to women — all of them friends of mine — cry loudly at my kitchen table. I’m seated on my living room couch, watching Hillary Clinton concede the election to a man who bragged on tape about sexually assaulting women. His rallies are regularly attended by people who espouse vile white supremacist views and throw up stiff-armed Nazi salutes. By happenstance, I am the only one sober for this nightmarish turn of global events. A dental crown came out that morning as I chewed on peanut brittle, leaving me unable to drink without my mouth erupting in sharp pain. So, I watch in gaping, horrified awe as everything I long feared about my country comes true.

The next morning, my wife and I begin the process of moving our family out of America.

JANUARY, 1964

Sam Cooke is a notorious control freak when it comes to the studio. He always has a vision of how he wants every instrument and the finished song to sound. It drives his collaborators mad. But for this new song, he feels he has no choice but to surrender to someone else’s guidance. Part of the reason might be that the song still doesn’t feel like his. It came to him too easily. Whatever is acting through him, he must continue to trust it – which is why he has given complete control to arranger René Hall.

Hall composes a symphonic arrangement within a three-and-a-half-minute framework. Each verse of Cooke’s song will be a different movement. The strings each have their own movements. A timpani will carry the bridge. People will one day rightly compare the ambitious grandeur of it all to a film score.

JANUARY 18, 2018

I’m standing at the window of my new home in London, my nine-day-old son strapped to my chest. It’s 3:30 or so in the morning, and the city is as asleep as it ever gets. I love it here, I feel more at home than I ever have in America, but I don’t trust it will last. Brexit has already ripped the country out of the European Union. Refugees continue to die in ever-growing numbers, trying to get into Europe any way they can; the influx of so many non-white people, most of them Muslims, is beginning to reveal cracks in other European countries’ politics. Nationalism and fascism lurk everywhere. Meanwhile, the news out of America is terrifying. My friend tells me someone shouted “N*gg*r!” at him as he walked home the other night, something that had never happened to him before in his life. Hate rhetoric is skyrocketing everywhere. Children are locked in cages along the border there. Protests and riots in the streets across the country.

So much for hope.

I climb back into bed, open my laptop, and begin to write what will become my debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD with my son still strapped to me. I haven’t written straight fiction in more than a decade, focusing instead on screenwriting. I’m terrified, but the words flow out of my fingers and race across the screen. Writing has rarely come so easily for me. This mix of compulsion and anxiety and exorcism scares me. But I cannot stop.

JANUARY, 1964

Bobby Womack has known his friend Sam Cooke ever since Cooke introduced himself to them in the mid-fifties; Womack and his brothers were touring on the gospel circuit as Curtis Womack and the Womack Brothers and Cooke was a member of The Soul Stirrers. They hit it off, and years later Cooke signed his friend to a contract with his personal label, SAR Records, as well as used him in his own band. Some might even call Womack Cooke’s protégé, which is why Cooke asks him to listen to and opine about this new song he’s recorded.

It’s called “A Change Is Gonna Come.”

Womack listens to the mournful sound of the complicated arrangement, to Cooke’s aching lyrics, to his friend’s voice that seems to vibrate with something supernatural. This isn’t a dance song or a love song or anything that would make audiences howl Cooke’s name as he performed it. It’s a complete departure, the first time Cooke has ever directly confronted the issues tearing America apart outside the studio. Womack knows Cooke was both deeply moved by Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” and frustrated that a white man had written such a poignant song about racism rather than a Black artist such as himself. Then again, Cooke has been hesitant for a long time to try such a thing himself; so much of his success depended on his large white fan base. But after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led the March on Washington last August, where he delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, perhaps Cooke has had a change of heart.

Cooke presses stop, and turns to his friend. “What’s it sound like to you?” he asks.

Womack can see how excited Cooke is about the song, how proud he is of it, but there’s something else in his face, too. Fear, he decides. Cooke is afraid of the song for some reason.

“Well, Sam,” Womack says, “it sounds…like death.”

Cooke nods several times, shaking his head at the same time. “Man, that’s kind of how it sounds to me,” he says. He looks torn, struggling with something unseen. “That’s why I’m never going to play it in public.”

SEPTEMBER 15, 2021

For the first time in seventeen years, Rolling Stone magazine remakes its 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list. This time around, I note that Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” lands at Number 3, an explosive leap from the Number 12 spot in 2004. It’s only surpassed by Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” and Aretha Franklin’s “Respect”.

Less than one year after Donald Trump was voted out of office, Rolling Stone has chosen three protest songs to top their massive list. There is the sense that this new state of things cannot hold. That somehow we have found ourselves no longer looking forward, but being dragged back into a more violent, darker past. Talking heads in the media and conservative politicians cry out for this regression, this shrieking ride down a playground slide to a time when women were barely recognized as human beings beyond the utility of their anatomy and Black people like Cooke, like his wife Barbara, like their friends could be turned away from a Holiday Inn simply because of the color of their skin. Everywhere I look, the value of human life seems to be rapidly crashing. It’s impossible not to despair.

FEBRUARY, 1964

Sam Cooke is arguing with his new manager, Allen Klein, a man who will go on to manage both The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. Cooke is due to perform two songs on “THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JOHNNY CARSON” to promote his new album AIN’T THAT GOOD NEWS that will be released in two weeks. Cooke wants to go with “Basin Street Blues” and the album’s titular track — not to mention his latest single — “Ain’t That Good News”.

But Klein wants his client to scrap “Ain’t That Good News” and perform “A Change Is Gonna Come” instead. It’s an audacious proposal, but he’s become infatuated with the song, convinced Cooke’s fear of it is irrational. It has a gravity to it, a spooky power — one might even say a transcendent spirituality — and the world needs it now more than ever, he insists. Cooke disagrees; besides, there’s no way they could pull off that kind of arrangement with such short notice.

Klein is a force not to be reckoned with. He makes RCA pay for a full string section and gets NBC to agree to it for Cooke’s Friday night appearance.

TODAY

I’m playing a double album on vinyl of Sam Cooke’s greatest hits for my family. I often make a habit of scooping one of my children up to dance to his songs. Even his poppiest numbers have an ethereal quality about them that I’ve always attributed to his gospel training. When “A Change Is Gonna Come” comes on, though, I can’t help but feel as I did when I was a child at church and my pastor asked his congregants to stand and sing along with him. I don’t sing when I hear it anymore, but something inside me shifts the way it still does when hymns fill up a church around me.

It's been too hard living, but I'm afraid to die

'Cause I don't know what's up there, beyond the sky

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

Cooke’s voice manages to sound like both a dirge and a soaring call to something greater than human hate and greed and whatever drives men and women to sabotage the chance any of us might make it through this life in one piece. It’s because the song is about hope, but hope that’s lashed together with faith - because faith is something the man had in spades since childhood.

The thing is, I don’t have any faith left, which is why I now understand I’ve become so wary of “A Change Is Gonna Come”. I can’t stop listening, but the world I’ve grown up in, the world I’ve reached middle age in, the world I’ve brought my children into has left me with no faith in any of the song’s lyrics. They feel like a naïve delusion to me. So many have fought and suffered and died just so we can end up here?

This tension, between Cooke’s yearning, pleading intent and the state of the 21st century sixty years later, perplexes and haunts me.

FEBRUARY 7, 1964

After singing “Basin Street Blues”, Sam Cooke returns to “THE TONIGHT SHOW” stage to perform “A Change Is Gonna Come”, but unlike “Basin Street Blues”, NBC doesn’t save a tape of the performance. A network timekeeper incorrectly logs the song as "It's a Long Time Coming”. It’s almost as if it never happened.

Allen Klein’s hope for the song becoming a milestone in Cooke’s career are dashed when, two days later, The Beatles perform on “THE ED SULLIVAN SHOW” for the first time. Watched by 73 million viewers, it is now regarded as a cultural watershed that birthed American Beatlemania and the start of the “British Invasion” of American pop music.

Cooke never performs “A Change Is Gonna Come” again.

Almost a year later, he is gunned down by a Los Angeles hotel manager. Eleven days after his death, the song inspired by another experience with a hotel manager is released and quickly becomes an anthem of the Civil Rights Movement and, later, the anti-Vietnam War movement. Over time, its meaning expands beyond its origins and it becomes a prayer for a better world.

TOMORROW

You feel it, don’t you? The creeping dread that the party is over and everyone’s just waiting for someone to flick off the lights on the way out. The Earth feels it, too. Every time we walk out the door, we must either pull the blinders on first or wrap ourselves in whatever stories we’ve chosen to help us survive against some terrible, unspeakable, wholly unimaginable truth.

This is what drove me to write PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD, which I don’t bring up again because my art has any special value. But I did write it to try to make sense of what I was feeling, what I thought so many of us were feeling as this terrible shadow fell heavier and heavier across our lives. Chapter after chapter, my characters vacillated between optimism and grueling physical horror and existential despair as they unwittingly searched for the same answer all of us are. I reasoned at some point that the book — which I had no expectation of ever seeing published — would reveal something like an answer to me. This answer never explicitly manifested, but I did recognize something about my work that I hadn’t before.

Time and time again, I’ve attempted to write something dark, maybe even nihilistic, anything to give form and features to the aforementioned creeping dread. If I could animate it, I could perhaps control it and even put it in its place (despite what the novel FRANKENSTEIN taught us about trying to control your monsters). But every single time, my exploration of despair eventually proved incapable of existing in that state for long. Something like hope warped and defied and remade my best efforts. This happens time and time again today, too, to such a degree I no longer even fight it.

There’s no way to make sense of the boundless horrors outside our doors. There’s no way to make sense of the faith that drove Sam Cooke to write “A Change Is Gonna Come”. And there’s certainly no way to make sense of hope as an idea. But maybe that’s because hope — while it is a noun — only really begins to make sense as a verb. It’s something we do, despite all evidence that it’s futile, because the alternative is even more impossible to comprehend.

Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” endures today because it speaks to this truth in our cells, in our soul if you prefer that terminology. It’s what makes it one of the greatest songs ever recorded, a hymn of hope for this time and all time. Of course, a change is going to come. How could it not?

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

Elements of this article dramatize documented historical events, but all effort was taken to not distort facts. Here are some of the sources I used, though many more were consulted as I worked on this.

https://www.npr.org/2014/02/01/268995033/sam-cooke-and-the-song-that-almost-scared-him

https://www.nytimes.com/1963/10/09/archives/negro-band-leader-held-in-shreveport.html

https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/music/2021/01/16/a-change-gonna-come-same-cooke-one-night-in-miami/6649395002/

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-lists/best-songs-of-all-time-1224767/bob-dylan-like-a-rolling-stone-3-1225334/

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Beautiful piece, Cole.

It makes me think too of Martin Luther King Jr's famous quote "The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice." A belief I hold on to in dark times.

Have you seen One Night In Miami..? It ends with this song, with Leslie Odom Jr recreating Cooke's performance on The Tonight Show. Hugely powerful.

Cooke was a groundbreaking figure in R&B music, and "Change", more than anything else he recorded, successfully merges the secular suffering of his race with the fervor of the gospel music he began his career singing.