When Norman Rockwell Got Woke: The Story Behind 'The Problem We All Live With'

In the 1960s, America's most famous artist defiantly transformed himself from an inadvertent white supremacist into a radical civil rights activist

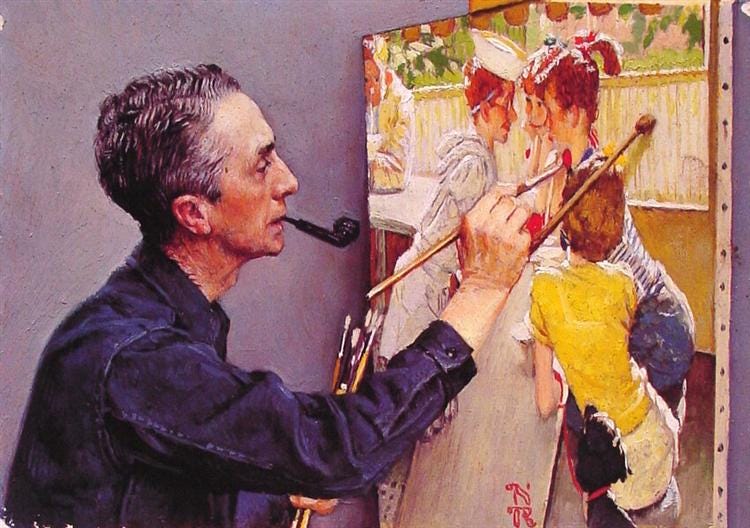

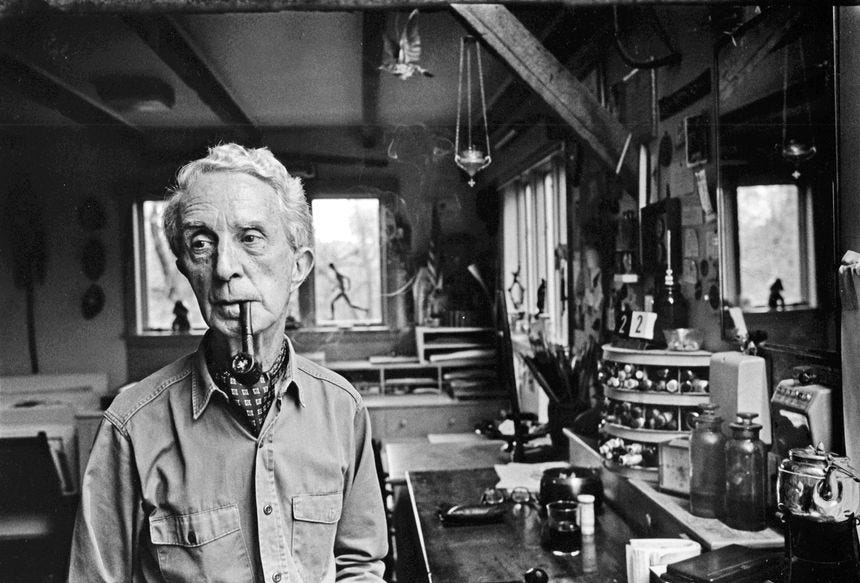

No artist has done more to create — or, maybe I should say manufacture — the American identity than Norman Rockwell.

Consider how wildly fragmented America’s immigrant identity was when the illustrator — as he described himself — began painting covers for the famed Saturday Evening Post in 1916. There was nothing to connect groups such as the Irish, Italian, Chinese, Swedish, or, in my family’s case, German and Polish with the English who had previously colonized much of the North American continent, the Mexicans who had become American with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the descendants of enslaved African peoples, or the Indigenous people whose land everyone else decided was suddenly theirs. As problematic was how distance separated immigrant groups from each other; in America, you could, for all intents and purposes, live as geographically separated from your extended family as you were from those back “home” in, say, Europe.

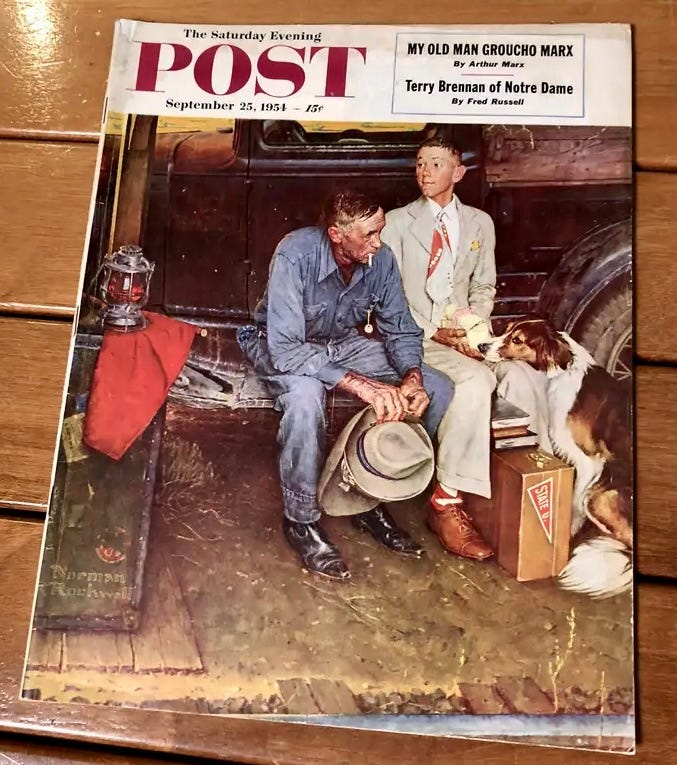

But once a week, the Saturday Evening Post appeared and, with its illustrated covers, told culturally diverse Americans, whoever they were, “what America was”.

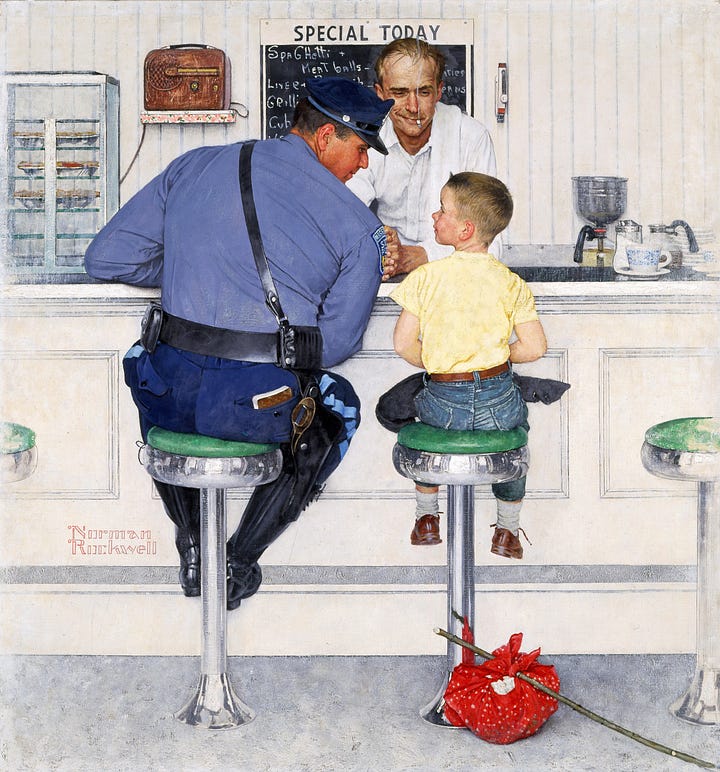

Through Rockwell’s relentlessly prolific work over the subsequent decades—which presented a sentimental ideal of Small Town, America, one where nobody locked doors, everybody ate apple pie, and people of color did not exist—he forged a popular collective vision of America. In other words, Norman Rockwell unwittingly created the idea of America that Donald Trump’s supporters so desperately want to return to…even though it only ever existed in Rockwell’s imagination and the films and TV series that would go on to simulate it.

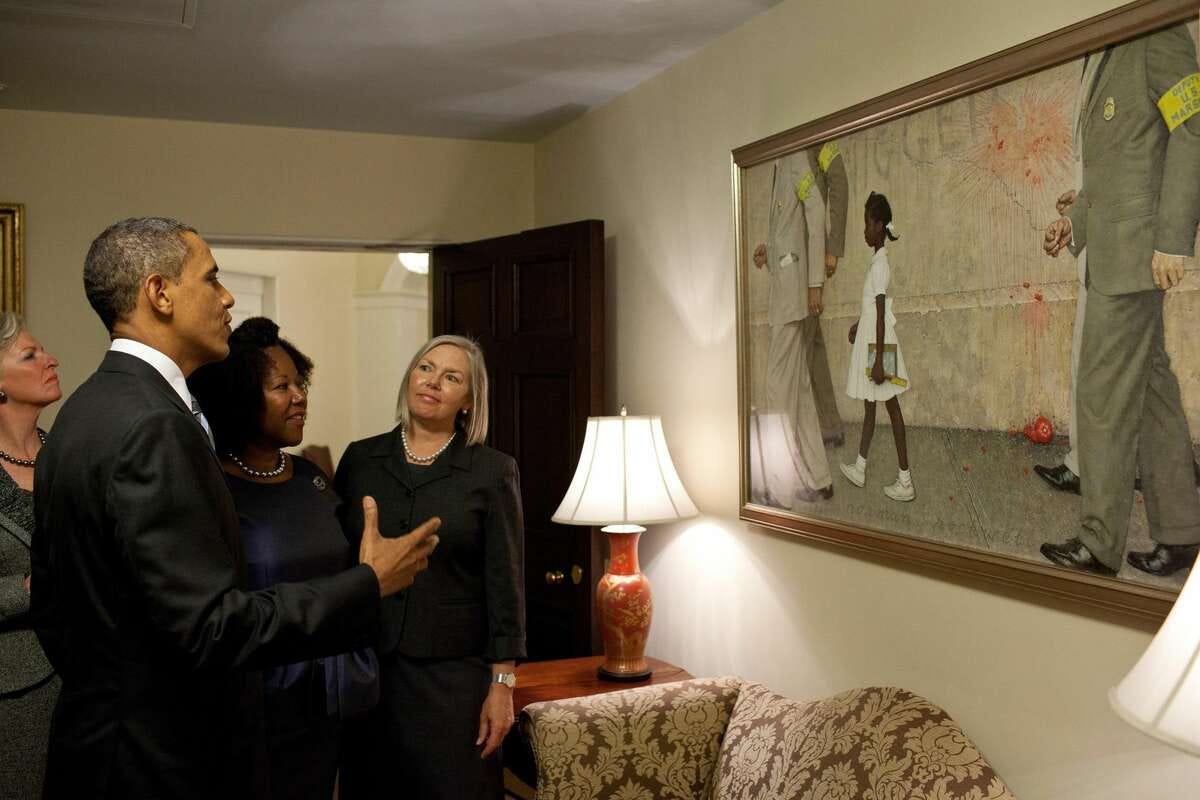

The irony is, this same artist, an inadvertent white supremacist standing at the threshold of retirement, also painted “The Problem We All Live With” (1964). It’s arguably the most important painting of the Civil Rights Movement, an image so iconic and still relevant today that President Barack Obama hung it outside the Oval Office after his election in 2008.

So, how did this happen?

I’m about to tell you the story of how Rockwell spent the sixties trying to change America by blowing up his legacy, make the case that the painting in question exemplifies the idea that one of an artist’s most important roles is to provide a mirror that helps people understand their world better, and, in conclusion, discuss what artists — from those who create with a paintbrush to those who tell their stories on the page and screen — can learn from “The Problem We All Live With”.

1960: THE YEAR THAT CHANGED ROCKWELL

To say Norman Rockwell was a complicated man is to put it mildly. I’m not even going to get into the very real possibility he was a closeted gay man, or the fact that his first wife was institutionalized, or that his second wife might also have been gay because…well…that’s too much drama for this piece. What is important in the context of this conversation is that Rockwell was a lifelong conservative up until the 1960 presidential election. Something happened that year that inspired a dramatic change in him—it would be fair to say, left him woke—though what remains a mystery as I’ll get into in a moment.

Up until the sixties, Rockwell’s work had been pretty much as white as you’d expect of him (that is, if you didn’t know about his later-in-life conversion to radical activist).

But what’s interesting about how lily white his work was is that he also made several attempts to integrate within his paintings over the years, only to be thwarted by his editors who had no interest in Black people on their covers. On one occasion, Rockwell even had to paint out a Black subject because the depicted Black man wasn’t in a service position – the only acceptable position for a person of color, according to the Saturday Evening Post. It’s easy and fair to fault Rockwell—by far the country’s most famous artist—for somehow not leveraging his celebrity to do more, but he was, as I said, complicated. Fear seemed to consume much of his life.

Then, 1960 happened.

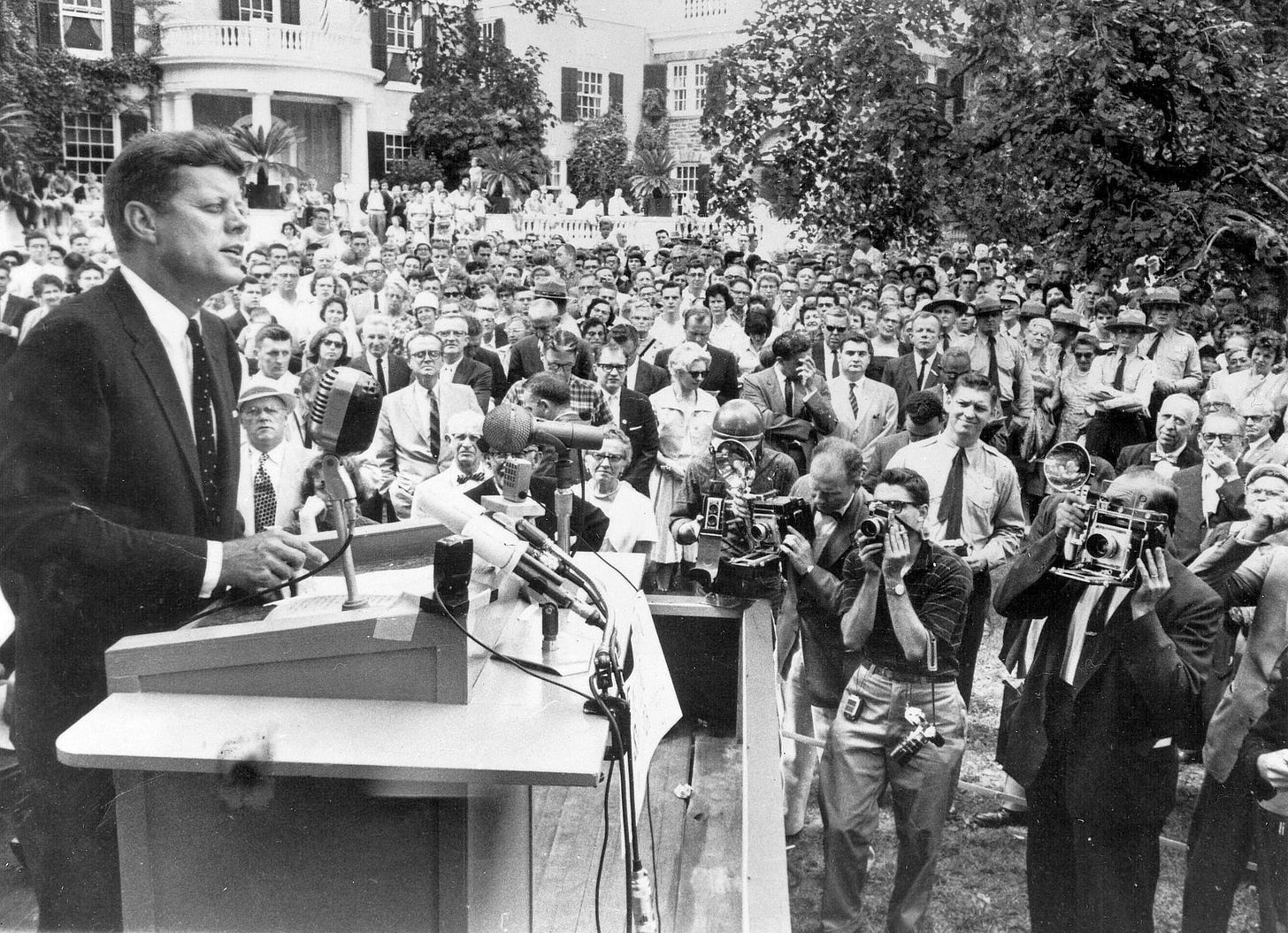

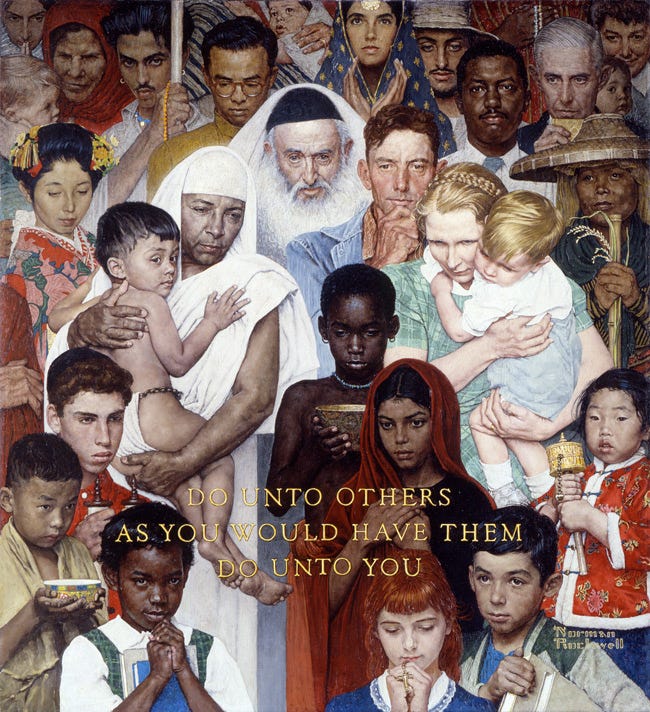

Rockwell suddenly became a Democrat, voted for John F. Kennedy, and, by 1961, managed to get the Saturday Evening Post to let him paint “Golden Rule” for them. The cover went to print in April of that year and featured a litany of faces and cultures from around the world. I understand how shocking this piece might have felt to many at the start of the sixties, but I’m going to say here it’s an incredibly safe piece, no more confronting or startling than a rough hug, and, in my opinion, even a bit cloying.

I call it a test run at what would come next.

Nobody knows what caused Rockwell’s transformation into a shout-out-loud Leftie because he never gave any interviews on the subject and his family has never been able to adequately explain it either. His actions don’t exactly provide clarification either.

For example, you can blame his support for Kennedy on how much he loathed Richard Nixon. He really hated Nixon. But you don’t have a political conversion of this grade because of how sleazy a candidate is.

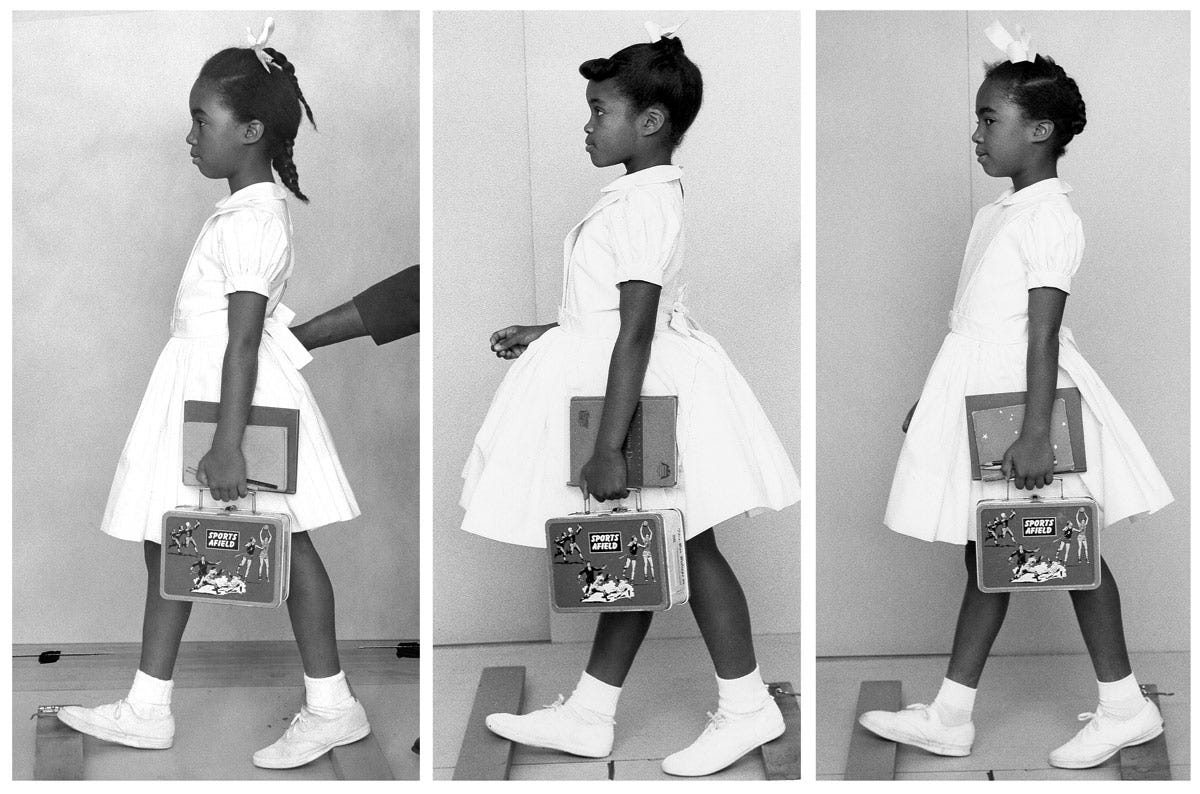

As for “Golden Rule”, I think it can easily be described as virtue signaling from a sixty-seven-year-old man whose relevance most people felt was rapidly dissipating as rock ‘n’ roll and very un-Rockwellian unrest shook the country daily on the evening news. “Golden Rule” would certainly have never signified more than that had Rockwell not three years later decided to paint Ruby Bridges, who was the first Black child to desegregate the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in Louisiana on November 14th, 1960.

I think it’s important to repeat that date: November 14th, 1960…six days after JFK’s election.

This is how The New York Times reported the event the next day:

Some 150 white, mostly housewives and teenage youths, clustered along the sidewalks across from the William Franz School when pupils marched in at 8:40 am. One youth chanted “Two, Four, Six, Eight, we don’t want to segregate; eight, six, four, two, we don’t want a [OMITTED].”

Forty minutes later, four deputy marshals arrived with a little Negro girl and her mother. They walked hurriedly up the steps and into the yellow brick building while onlookers jeered and shouted taunts.

The girl, dressed in a stiffly starched white dress with a ribbon in her hair, gripping her mother’s hand tightly and glancing apprehensively toward the crowd.

Something about the sight of Bridges on television, this little girl besieged by howling racists hurling epithets at her — so horrifying censors had to muffle them for audiences at home — stuck with Rockwell. It rooted itself in his consciousness and maybe even his conscience, where it grew for more than three years until he made the extraordinary decision to put paintbrush to canvas and, in doing so, attempt to blow up his reputation and legacy. He would betray the white Americans who had come to trust him over the previous five decades in a desperate bid to awaken some forgotten decency in their race (and maybe find some redemption of his own).

THE PAINTING

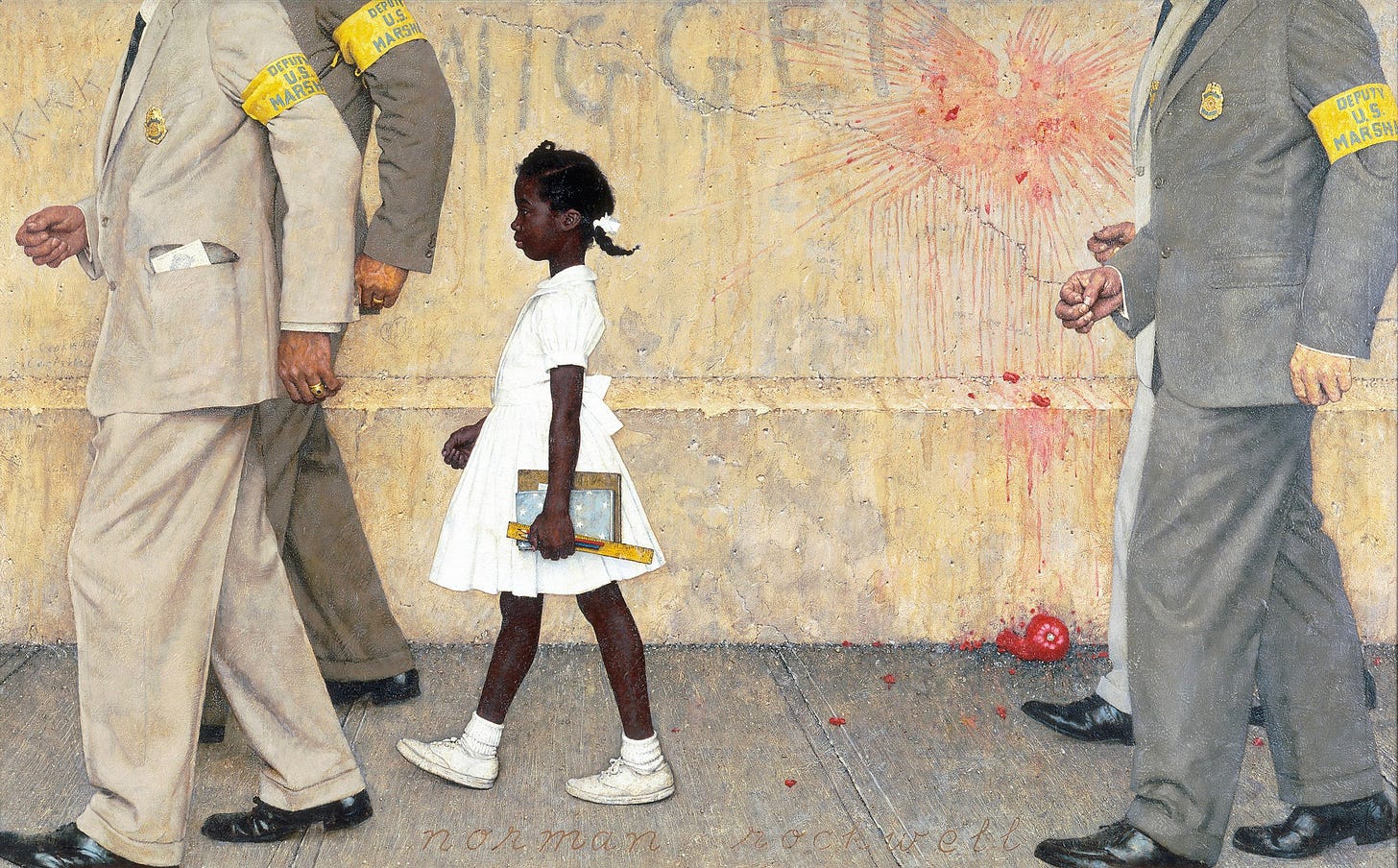

Let’s take a look at the painting in close-up now. It tells an incredibly detailed story you might not notice at first, one which provides a powerful lesson to aspiring artists about how to make your audience participants in your narratives. More on that in a bit, but pay attention to how what I’m about to talk about applies to storytelling of any kind, from fiction to music to filmmaking – and, of course, fine art.

To begin, “The Problem We All Live With” wasn’t published in Rockwell’s longtime home Saturday Evening Post. Instead, he had to turn to Look magazine, which was intrigued by the idea of helping Rockwell weaponize his reputation to rattle the sensibilities of white Americans (I tend to think the editor just liked the idea of boosting its subscriptions by letting this famous old white guy commit a dramatic public seppuku).

The painting appeared as a two-page centerfold on January 14th, 1964. You have to imagine what that would’ve been like, too, because this painting, unlike “Golden Rule”, is confronting. Everything about it grabs your attention and doesn’t let go – even as it turns your stomach.

RUBY BRIDGES

We’ll start with the little girl the painting appears to be focused on, though it should be noted that Ruby Bridges wasn’t identified by name for many years afterward. As a result, she became a nameless victim, a nameless symbol for every Black child in America.

Rockwell almost always used models, and in this case, he was hard-pressed to find young Black girls in his New England community to pose for him. In the end, he used Lynda Gunn and, on occasion, her cousin Anita Gunn.

The figure in “The Problem We All Live With” — let’s just call her Ruby — is confidently poised in her white dress. A bow in her hair. But notice how dark her skin is. Her Blackness is screaming at you on purpose, in stark contrast to the much-lighter imagery around her. You might almost say it’s a black-and-white image with one real exception. She’s one of two elements in this image that immediately strike you as out of place, the other being the bright red tomato splatter – though there is a third, slightly more buried, that I’ll bring up in a moment.

THE U.S. MARSHALS

There are three key details about the marshals escorting Ruby Bridges worth considering:

--Their rhythmic cadence, almost as if in lockstep. They are doing a job for the state, an assigned task, in which who they are – and their personal convictions – is/are irrelevant. The government has come to the rescue (Rockwell never really stopped believing in law and order, even after his sixties awakening).

--The cropping of the marshals’ heads, making literal their anonymity. They represent law enforcement everywhere as a result, honorable agents of the government’s law. Like the nameless Black child in this painting, they are a symbol of something bigger.

--Their suits, which aren’t the dark grey or black you would expect them to be wearing at this point in history. This decision was clearly made just to contrast with Ruby’s dark skin, pushing her and her innocent young face into our focus.

THE WALL

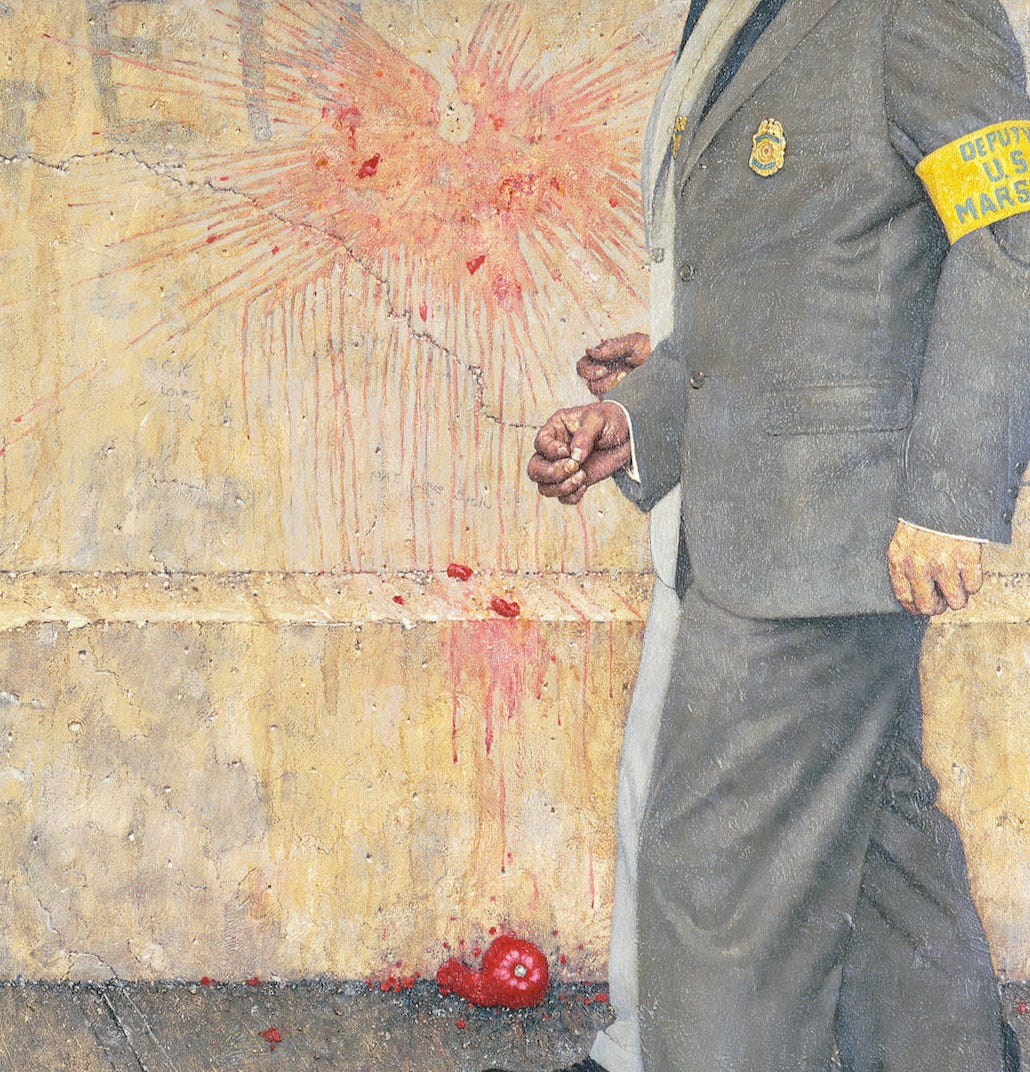

So, as much as Ruby Bridges appears to be the focal element of this piece, there are two others that are as incongruous as she would have been in 1964. The tomato, as I mentioned, but also the N-word graffitied across the wall.

The tomato has detonated, creating a starburst of gory splatter. Remnants of it on the ground like brain matter. There is a dramatic intimation of violence here. Of murderous intent. It’s the source of the painting’s entire dramatic tension as, without it, the marshals and the N-word would leave a viewer confused.

Rockwell’s point is clear: people showed up to see a Black child bleed. We’ll get into what kind of people in a moment.

As for the N-word, it contextualizes the conversation the painting is having with viewers. If you’re unsure about where this piece fits into American history, don’t worry, now you know. It’s brutal and shocking and, as I’ll also explain in a moment, an indictment of the people who showed up to torment this child.

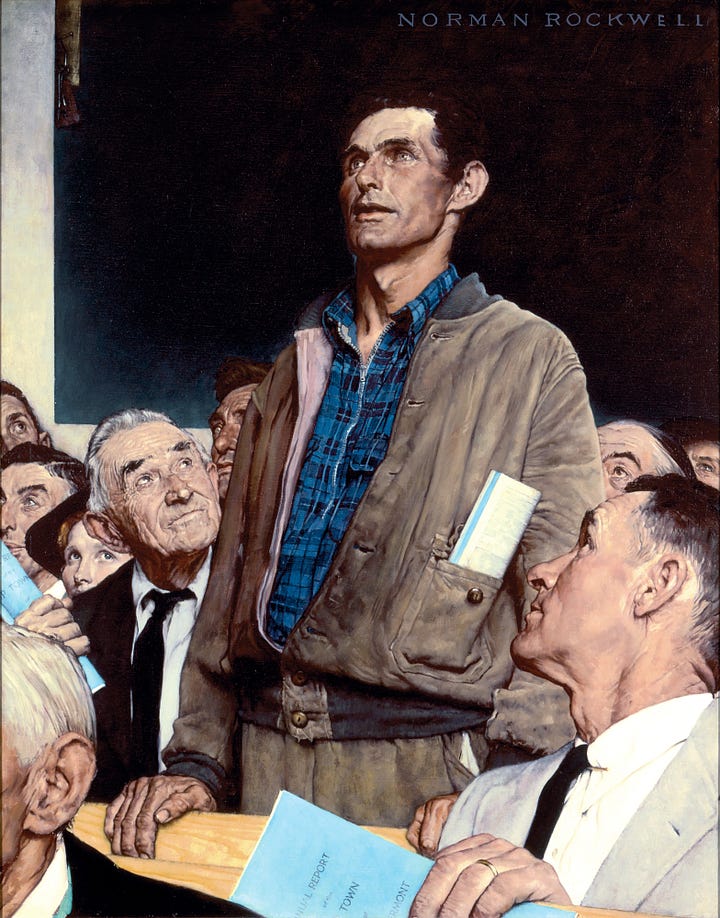

YOU

Look at “The Problem We All Live With” again. Imagine it on the wall in front of you. Where are you positioned in the context of the action and tension it is conveying?

The answer is the reason why looking at this piece is so uncomfortable for non-Black people (but especially white people): you are the crowd.

You are the one who just hurled that tomato at a young child.

You are the one who just called her the N-word.

You are the one still calling her it as she passes by, making sure the word, how you shouted it at her for just wanting to go to school, reverberates in her memory for the rest of her life.

You are the one who came here to hopefully watch her bleed.

You are the problem we all live with.

The painting isn’t just a painting. It’s a reflection. Like the greatest art ever created, it holds a mirror up to us, it shows us who we are, and it is merciless in its judgment.

WHAT STORYTELLERS CAN LEARN FROM “THE PROBLEM WE ALL LIVE WITH”

Take another look at the painting. Where you sit in the action it’s conveying. Norman Rockwell made you a direct participant in the story he is telling. This is something it is endlessly worth artists asking themselves about their own work:

Is my audience being made to feel like they are participants in my work? Are they part of the action, part of the story? Have I blurred the lines between what is happening to my subjects and what my audience feels is happening to them?

This is not to say all art requires the audience to directly participate in the story they’ve been asked to engage in, but when it is, when the audience is in it, they will always feel more invested. In the case of a novel or screenplay, for example, this is especially valuable. It compels readers to keep turning the page, hopefully faster and faster, to escape whatever situation you’ve put them — not just your characters — in.

FROM ACCIDENTAL WHITE SUPREMACIST TO CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVIST

“The Problem We All Live With” was Rockwell’s first true piece of art, that wasn’t a fantasy – a kind of cultural and emotional propaganda.

As Murray Tinkelman, former Chairman of the Hall of Fame Committee of the Society of Illustrators said of it: “A painting like this depicting this subject matter, done by somebody who is embraced by the most conservative elements in our country would make these people stop and think that maybe there is a problem. And the problem is racism. Purely and simply.”

The result unsurprisingly earned Rockwell the first hate mail of his career, much of which declared him a race traitor. Even in the sixties, frothing conservatives resorted to threats of violence against artists who disagreed with them. Rockwell didn’t stop there either, spurred on in some way by this vitriol. His progressive activism evolved to include the anti-war movement, but never forgot America’s race situation — most famously “Southern Justice (Murder in Mississippi)” in 1965 (also for Look).

If there’s a lesson to be learned from his transformation, it’s that you’re never too old to change, to grow, or, in the case of Rockwell, atone for what I believe he eventually saw as a career predicated on perpetuating white supremacy. If he were alive today, he would no doubt be taking the MAGA movement and mass shootings on and defending LGBTQ+ rights with the same fearlessness he demonstrated throughout the twilight years of his career and life.

You might also enjoy this arts essay from me: “Artemisia Gentileschi on How to Properly Decapitate a Man”.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

Still want to see the cinematic version you wrote on this...

Outstanding essay! I had no idea about Rockwell’s history, conversion, and his later works. Your breakdown of the Ruby Bridges painting was like attending an art appreciation class. I’d watch a biopic on him, though knowing WHY he had this seemingly sudden conversion would be of great interest to me.