Artemisia Gentileschi on How to Properly Decapitate a Man

Let's break down the Italian master's 'Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes' - one of the most transgressive art works of the Renaissance

Throughout my childhood, my only access to the Detroit Institute of Arts were school field trips. Without them, I wouldn’t have even known the museum existed, as my parents weren’t curious about the fine arts at all. While I can’t be sure on which of these brief visits I discovered the painting JUDITH AND HER MAIDSERVANT WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES that hangs on a wall there, the impression it made was immediate and lasting. Call it the gateway drug to fine art for me. When I got my driver’s license years later, I began to return to the DIA far more frequently, but for some reason, it never dawned on me to double-check the name responsible for the artwork. Somewhere along the way, I had decided Caravaggio painted it. Why? Probably because its real painter was a Caravaggian herself…though with her own very Florentine, very personal spin on the iconic Roman painter’s shadow-drunk style. That real painter?

Artemisia Gentileschi.

Here’s what you need to know before I introduce you to the painting by Artemisia that made a teenage me’s knees wobble:

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1653) was already a master by the age of seventeen— and, ultimately, was the only female master of the Italian Renaissance.

Around seventeen, she was violently raped by her father’s painting partner. Her father Orazio Gentileschi was a painter, too, though already it was clear his daughter was superior to him in every way.

After Artemisia astoundingly got her rapist thrown in the clink, she moved (was exiled) to Florence where she became the first woman ever admitted to the city’s all-powerful Academy of Design. She dazzled and intimidated and infuriated all the swinging dicks there with her novel marriage of Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro, vivid Florentine colors, killer handling of fabrics, and naked women who looked like real naked women (you couldn’t legally hire models at this period, but it helped to have your own lady parts and lived understanding of how they move).

She was also really, really good at painting women messing men up. In fact, she was the first person to paint the Biblical Susanna — you know, from the rape of Susanna — fighting back against the creepy elders attacking her. Classical art was quite often pornographic, which is just a polite way of saying rich men used to commission and buy a lot of paintings of women being spied on while they bathed or were otherwise being sex-crimed, then explained it away to their creeped-out wives by insisting, “B-B-But it’s art, baby!”.

There’s a lot of debate about whether Artemisia’s vengeance paintings — and there were quite a few of them — were motivated by her aforementioned violent rape. This is no doubt because many don’t wish to see the breadth of her career and accomplishments be defined by her sexual assault, especially after all those accomplishments were brushed under the rug for three centuries as soon as she died since her male peers really hated being showed up by a woman. It’s also right to point out that SUSANNA AND THE ELDERS pre-dated her rape by a year. But at the end of the day, there’s really no getting around the fact that she revolutionized the agency of women in the classical arts by turning a lot of those women on the vile men in their lives. It’s a correlation I feel very okay making.

Now, before I show you Artemisia’s JUDITH AND HER MAIDSERVANT WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES—and I’m getting there, don’t worry—do you even know who Judith and Holofernes are? Wikipedia to the rescue…

The story revolves around Judith, a daring and beautiful widow, who is upset with her Jewish countrymen for not trusting God to deliver them from their foreign conquerors. She goes with her loyal maid to the camp of the enemy general, Holofernes, with whom she slowly ingratiates herself, promising him information on the Israelites. Gaining his trust, she is allowed access to his tent one night as he lies in a drunken stupor. She decapitates him, then takes his head back to her fearful countrymen. The Assyrians, having lost their leader, disperse, and Israel is saved.

Nice one, Judith.

You might wonder how other great painters have approached this epic subject.

Here’s one by Reubens. Notice the look on Judith’s face: “You want some of this? Yeah, I’m down.” And if you’re confused how you should feel looking at this, she’s yanked her boob out to let you know she’s ready to party.

And here’s Caravaggio’s take on the subject, one which Artemisia and Padre Orazio would’ve been familiar with. I think what impresses me most about this is the ninety-pound waif standing in a “ewwww, yuck!” position while wielding a heavy short sword with one arm. All I see is Cher from CLUELESS.

Orazio had his own take on the material, which predates his daughter’s. He went for…humor? I can’t tell what’s happening here. Judith seems to have heard something while her maidservant is more concerned by a moth flitting about the top of Holofernes’s tent. It feels like a Biblical buddy comedy starring Aubrey Plaza and Rebel Wilson.

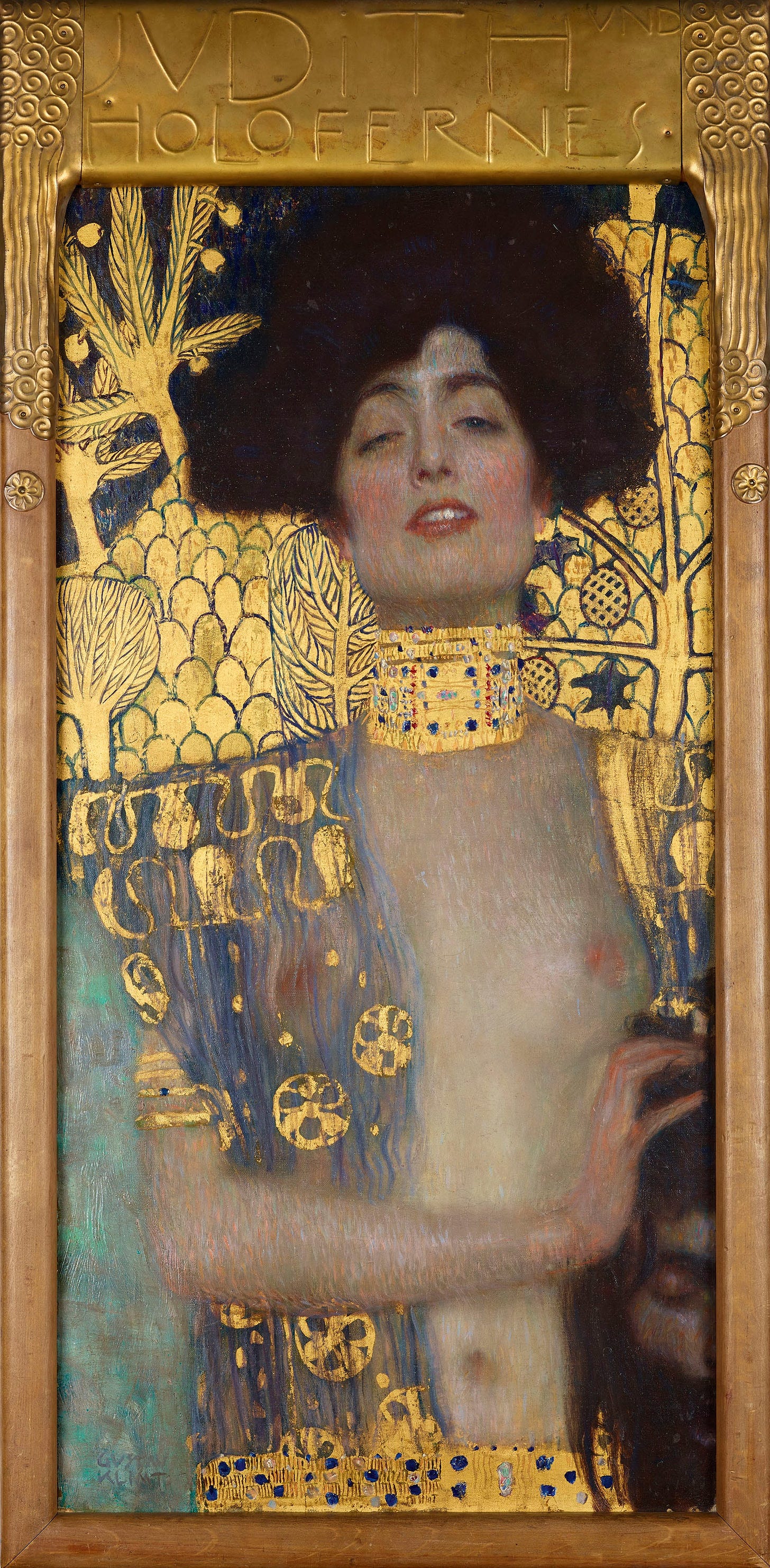

And then, there’s the most famous take on Judith. So famous, people travel to Vienna specifically to see it — Gustav Klimt’s JUDITH AND THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES, which he painted in 1901. Another “come hither” gaze despite the world moving on from the Middle Ages and Renaissance, still more exposed boob than you would expect to be present at a clandestine decapitation.

You now have a sense of Judith’s role in art history has been. In short: as a pornographic sex symbol, quite often blending nudity with extraordinary violence to create art for people with very a specific kink.

And so without further ado, here’s one of the ways how Artemisia Gentileschi, the only female master of the Italian Renaissance, the only significant female painter of the period anywhere in Europe — and one of my favorite painters period — tackled Judith.

Now, consider the story being told in Artemisia’s painting, because so much action is implied — all of it with no interest in giving a man an erection of any kind.

Judith and her maidservant have just ambushed Holofernes in his tent. Poor guy. He’s lost his head, which the maidservant is collecting right now.

“Holy shit, did you hear that? I think I heard something. No, I definitely heard something.” “Is someone coming?!” Judith holds her hand up, to obscure the candlelight so her eyes can gaze outside the tent better, leaving her face in intense shadow.

Both women are completely cool with what they’ve just done except for a desire not to get caught. Artemisia actually seems as if she’s been doing some thoughtfulness apps, because she’s in the moment. Her maidservant is far more nervous than her, but she’s not going to lose sleep over what she just helped do when she gets home.

This is a painting about violence against a violent man.

Standing before it as a child — and it’s large (73 11/16 × 55 7/8 inches) — it captivated and terrified me. While I can’t remember that far back with anything like true clarity, I do know what was on display at the DIA back in the eighties and what stuck in my memory, and it’s very likely this was the first piece of fine art that made me ask, “What does it all mean?”

Over the years, I’ve enjoyed digging deeper into that question and discovering the wonders of Artemisia Gentileschi. Hopefully I’ve inspired you to learn more about her, too.

If this article and the time I spent on it added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is now available from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. Paperback will hit shelves on May 25th. You can order it here no matter where you are in the world:

I love her choice to paint his head with greyed skin, relegated to the shadows and bottom of the painting, contrasting with the lush textures and deep hues of the women and furnishings. Not only has she given the women agency, she’s taken away from him everything that made him human. He’s nothing. I also enjoy seeing her Judith as a mature woman. Who’s in front of the easel makes a difference. Wonderful post; thanks.

I was lucky enough to go to an exhibition of her paintings at the National Gallery in London a few years ago. The thing about her women is they are capable. No fawning, fainting maidens; women with strong forearms and dirty fingernails. (And her early Susannah is just so annoyed at those pervy elders. You can just hear her saying “fuck off, creeps!”)