Denis Villeneuve, 'Dune', and the Problem with Dialogue Today

Let's talk about what the director meant when he declared he hates dialogue and, in doing so, explore the oft-forgotten narrative power of silence in screenwriting

"I felt a great disturbance in the Force, as if millions of voices suddenly cried out in terror and were suddenly silenced,” Obi-Wan Kenobi declares in Star Wars: A New Hope. “I fear something terrible has happened."

Ironically, I thought of this very specific line of dialogue when, a couple of months ago, Denis Villeneuve declared, “Frankly, I hate dialogue.”

He said this to The Times of London while promoting Dune: Part Two, which he co-wrote and directed, and in an instant a million screenwriters — both aspiring and professional — suddenly cried out in terror on social media.

Well, maybe not a million. But, you know…a lot.

Because of this, I want to discuss with you the role of silence in cinema, why it’s still screenwriting, and why, yes, everything from creative executives, to agents, to screenwriting guides have turned a lot of feature films into unnecessary blabberfests that can deprive audiences of the cinematic experiences their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents had. As I write, bear in mind that I’m a screenwriter and a novelist. Words matter deeply to me. But cinema isn’t just words. It’s images, too. It’s about manipulating time and space within a film to create new meanings that wouldn’t be there otherwise. Screenwriting can be the spark for and help facilitate this - but a script alone is not a film.

Scripts don’t change lives as much as we want to believe they do.

Films do.

“Dialogue is for theatre and television,” Denis Villeneuve continued, speaking with The Times. “I don’t remember movies because of a good line, I remember movies because of a strong image. I’m not interested in dialogue at all. Pure image and sound, that is the power of cinema, but it is something not obvious when you watch movies today.”

“In a perfect world,” he explained, “I’d make a compelling movie that doesn’t feel like an experiment, but does not have a single word in it either. People would leave the cinema and say, ‘Wait, there was no dialogue?’ But they won’t feel the lack.”

For a full twenty-four hours after these words were reported, it was all screenwriters seemed capable of talking about on social media - especially those without a sale or credit to their names.

“Gasp, did you hear what that bad man said about dialogue? What would Casablanca be without, ‘Here’s looking at you, kid’? What would Jaws be without, ‘We’re going to need a bigger boat’? What would Madame Web be without, ‘He was in the Amazon with my mom when she was researching spiders right before she died’?”

I reference the experience level of many of those complaining for reasons that will become clearer later on, but I’ll summarize here: The art of screenwriting, for a variety of reasons, has become polluted by the notion that only dialogue counts. I find newer screenwriters typically don’t grasp how much more important almost every other aspect of a screenplay is. That might be triggering, but, again, I’ll explain more as I go on.

Villeneuve, who is clearly less comfortable speaking English than French and can sometimes fumble his words, felt the need to clarify his statements after the reaction to them. Maybe a few screenwriter friends of his were like, “Qu'est-ce que le fuck, mon ami?” I wish he hadn’t, though, because I think his intent was obvious. Here’s his statement to Sharp Magazine:

“It’s true that I said that […] laughing. So, [when] I said it, I put a lot of emphasis on ‘I hate dialogue.’ I don’t hate dialogue. I am not inspired by scenes that are overwritten with dialogue — that’s the truth — and I’m talking about my own work.

“Of course, a lot of directors are brilliant dialogists, and there’s a lot of strong movies that are filled with great dialogue. But if I think about my own work, it’s [ideal] for me as a filmmaker to try to avoid the use of dialogue as much as possible. I think dialogue is the tool of expression for theatre, and then it became, for other reasons, one for television.

“I will say: in a perfect world, you should use dialogue only when there are no other resources […] It should be the last resort — that’s what I’m saying. When I say, “I hate dialogue,” it’s not true. I don’t. But it’s true that I feel, myself as a film director, uninspired when I read 500 pages of dialogue. For me, it’s boring.”

Brace yourselves, guys, because I have a secret for you: most dialogue is boring.

Do you know why?

Most people can’t write it very well. Aaron Sorkin can. Phoebe Waller-Bridge can. Quentin Tarantino and Martin McDonagh can. There are obviously hundreds of others I could also list, especially playwrights, but the reality is that most people don’t have an ear for constructing bullshit dialogue that sounds real.

Why do I say “bullshit dialogue”?

Because people rarely speak in real life like they do in films and on TV. No ums, never getting lost in thought, always stumbling on the perfect cutting or hilarious observation - you get it.

Film/TV dialogue has to somehow sound “authentic” under the duress of a running time and an expectation of being entertaining or something similar, which isn’t exactly how any of us communicate. Film dialogue is a special skill, is my point. TV dialogue is a special and very different skill. It takes years of practice to truly master them. Until then, most of us just get by writing passable to very good dialogue.

To make matters worse, most Hollywood producer/studio notes strip or otherwise sand away the edges of any script that expects its audience to think in any way. Ambiguity is generally only tolerated from directors who can somehow guarantee their faith in audiences’ historic capacity to grasp artful approaches to narrative and thematic revelations. Even then, it’s rarely the case that it’s permitted. (I recently wrote about our culture’s problem with ambiguity in film, which you can read here: “'Civil War' Highlights a Growing Divide in American Culture...and Not in the Way You Think”.)

How many times have you seen characters on your screen outright lay out rules or plot points for audiences? This used to be typical in network TV, especially procedurals; people watching at home were expected to run to the fridge or bathroom, so refreshers after every commercial break were helpful. But now, much of feature writing does the same.

I’ve never been able to work out how this problem arose. Meaning, if it was a creative problem that trickled down from producers and studios execs or one that evolved from horrible, reductive screenwriting guides that sought to turn an art form into a paint-by-numbers exercise.

The point is, many screenwriters today waste a lot of time talking about their plots on the page and on screens. Either they do this because that’s what they see in “successful films” and/or on TV, because screenwriting guides told them to, or because, as professionals, they’ve become acclimated to the kinds of notes they’re regularly given. Probably a mix of all three.

I’m no different, mind you.

For years, the quality of my screenwriting deteriorated as I found myself preemptively answering producer notes as I worked. Dumbing the read down in advance, I suppose you’d say. After all, there are only so many times you can hear some version of “I know this note will make the script worse, but it will help us get it made.” It wasn’t until I moved to the U.K. and started working with British producers that I realized what I had done to my work.

Then, I spent eighteen months working on a script with director Park Chan-wook (Oldboy).

At every turn, Director Park rejected any notion of such narrative obviousness. I began to cut dialogue right and left and use scenes transitions and contrasts and character decisions alone to progress the plot rather than characters “thinking aloud” about what they were doing. Don’t get me wrong, dialogue was still very much necessary, but it just became very obvious a staggering percentage of it was not for the script to work. The room this freed up meant more time for smaller character moments that typically spoke more loudly than words.

As I said earlier, I wish Denis Villeneuve had not offer a clarification about his original comments. They were obviously about his specific approach to filmmaking, as he later made explicit. They were also subjective, which is something artists should understand instead of panicking over the fact that one of the greatest living directors doesn't think words are as powerful as images to tell a cinematic story.

Here’s a great example of what Villeneuve does so well. This is how Princess Irulan looks when you first meet her in Dune: Part Two:

She is the daughter of the Emperor, educated by the Bene Gesserit to co-rule the galaxy one day (all of this makes sense if you’ve seen the film or read the book). And she begins the film as the brilliant daughter and heir to an empire, only to find herself slowly transformed into a political pawn…

…with increasingly no autonomy…

…until even her voice is taken from her altogether.

A whole character arc expressed in images alone.

Villeneuve is not alone in his faith in the moving image alone as a perfect conveyer of narrative. Everyone from Alfred Hitchcock and Ingmar Bergman to Yasujirō Ozu and Christopher Nolan — and plenty of other filmmakers — agree with him.

Let’s not forget that one of the most important — if not the most important — sequences in cinematic history had no dialogue. I’m talking about the Odessa steps scene in Battleship Potemkin. Yes, it’s a silent film, but that’s irrelevant. The visual storytelling was so important, so powerful, so revolutionary to the art form itself that audiences today regularly experience films influenced by it with no understanding of the source. Here it is:

So, how many other films did you notice in this sequence without, perhaps, knowing where they originated? That’s because Potemkin’s director, Sergei Eisenstein, pretty much invented what we consider cinema today. Here’s the most famous and obvious riff on his work in it, taken from The Untouchables (1987):

Notice anything about the Untouchables sequence? Yeah, no dialogue. Director Brian De Palma even strips it out of the mouth of the mother when she screams something as potentially powerful as “My baby!”

(Also, hot damn, what a scene!)

My question is, do you think nobody wrote that sequence in The Untouchables despite its lack of dialogue? Jon Sphaits co-wrote both Dune films including all of their long silences; I assure you, he wasn’t there just to smile and nod at storyboards that Denis Villeneuve showed him of what the films were going to look like. You can read Dune: Part One here if you don’t believe me.

I mean, for fuck’s sake, did we all collectively forget there’s a screenplay for The Quiet Place (2018), right? Though I suppose I should point out the whole town passed on that script went it went out as a spec. It took Michael Bay, a director who knows a thing or two about noise, to realize how special a script with no dialogue was.

Which I suppose is a good place to wonder aloud, when did so many film industry types — including so many screenwriters — become convinced dialogue was screenwriting and everything else is just filler? This became painfully obvious to me when a screenwriter accused the co-screenwriters (and director) of The Holdovers (2023) of plagiarism. While the accusation does appear without adequate merit (which is why I won’t link to it), the reaction from far too many WGA writers was that the dialogue in the two films was different so it couldn’t have been plagiarism.

I’m not joking, I saw this comment made a lot.

Meaning, according to many professional screenwriters, you can copy and paste an entire film as long as you change all the dialogue. It was very disconcerting. I don’t believe this is a widely held belief, but it is a belief held by a significant number of such screenwriters and an even larger percentage of aspiring screenwriters judging by the discourse on many of the screenwriting boards/groups I frequent.

One reason we might’ve ceased to value scene and plot construction over flamboyant language could be how lazy many of the people who profit off screenplays have become.

Time and time again, I’ve been advised that, “Most people don’t read scenes. They read dialogue.” By the way, this is almost certainly the reason nobody “got” The Quiet Place when it first went out to buyers.

We’re told over and over that if our dialogue isn’t singular, then we don’t have “a voice” and, by implication, are not employable screenwriters. Agents, producers, studio execs only want to read dialogue that leaps off the page like Diablo Cody’s, for example. And it’s true, Diablo’s does. Juno? God, what a great fucking read.

But you know what else is brilliant about Diablo’s scripts? The way she chooses to tell her stories, how scenes build on each other, how character decisions complicate the narrative, how she weaves her themes through her characters and plot, and how she is constantly one step ahead of her audience. I would never dare reduce Diablo’s work to dialogue alone - both because that would be silly and because it would diminish all the other powerful narrative skills she possesses.

But hey, if your scripts lack dialogue to explain what’s happening, good god, there will be blood.

The spec I wrote that landed me my first manager also revealed to me how true the axiom is that most people only read dialogue. My entire opening sequence was silent. No dialogue at all.

The note I got back was that the script was great except my action teaser. It was dragging. The manager couldn’t put their finger on it, but they wanted me to take another crack at it. After consulting with a professional screenwriter friend of mine, I came up with a solution. I inserted one line of dialogue — the word “Jump!” — into Page 1.

That’s it, nothing more.

I emailed my “new” draft back to my manager, who promptly replied that they didn’t know what I’d done, but it was great. They sent it out to producers the following week.

I still hate that “Jump!” by the way. I find it an embarrassing inclusion. Because I agree with Villeneuve and Park Chan-wook and so many other great filmmakers – the goal of every screenwriter should be to cut out every unnecessary line of dialogue that they can.

Don’t get me wrong here. I don’t “hate dialogue”. In fact, I love films choking with great dialogue. I will rewatch the hell out of When Harry Met Sally… I write both, too.

But knowing how to write scenes with only the most essential dialogue is incredibly helpful. In doing so, you might even get amazing scenes like this one from this lame hack director you might’ve heard of named Steven Spielberg. He started one of his films with a nine-minute-long sequence featuring no dialogue.

Again, do you think screenwriter Melissa Mathison wasn’t involved in dreaming up this nine-minute sequence in ET? Of course she was.

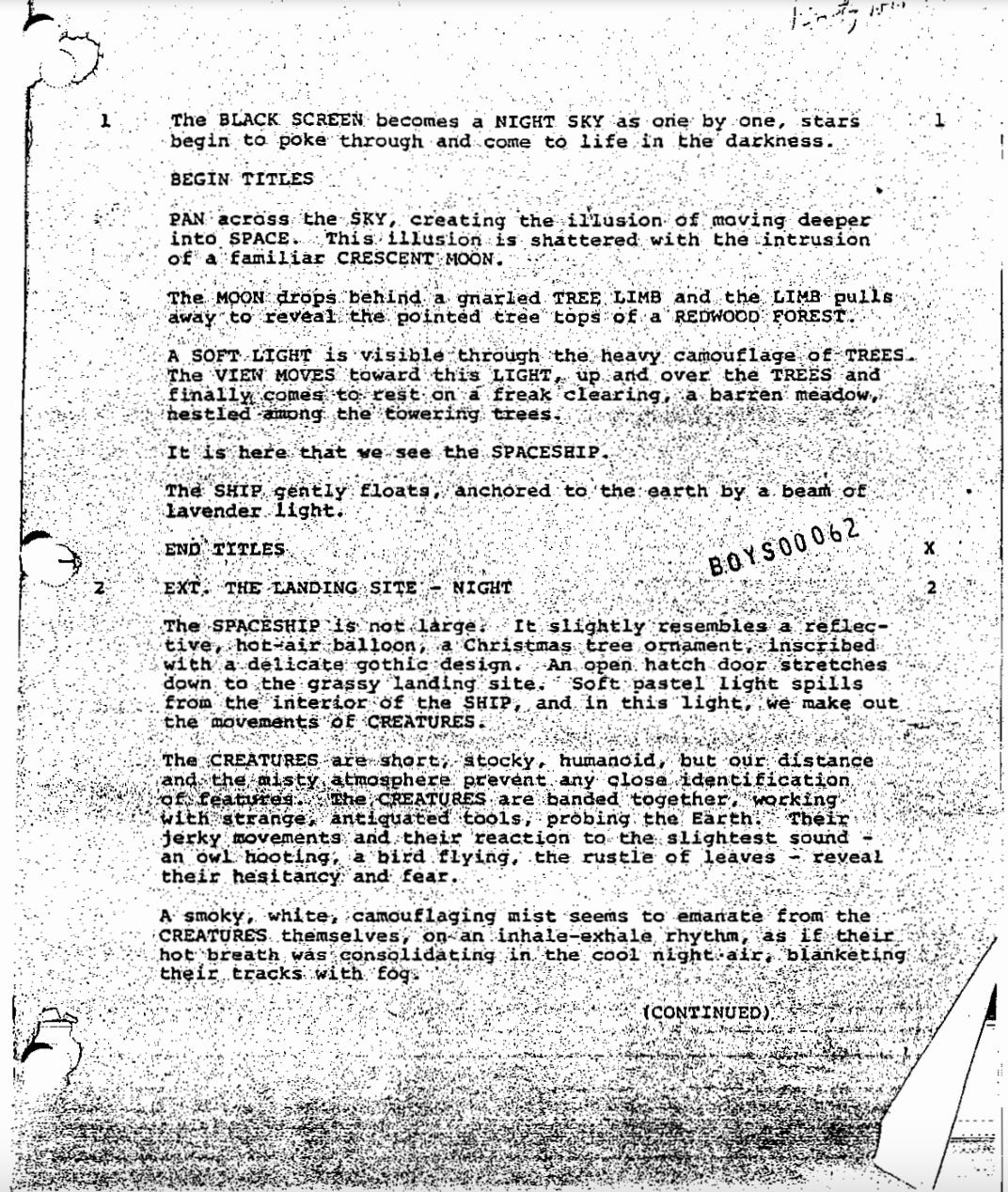

Here’s Page 1 of her script. The next six pages look exactly like this. No dialogue.

Yes, a screenwriter did that.

Spielberg has used this narrative trick a lot in his career if you think about it. He loves silence. The opening of Jaws? There’s some mumbled dialogue, a few snatches of it, but the whole sequence, through the shark attack, is essentially a silent film. The opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark? Ten minutes with a few lines of dialogue, nothing more.

In closing, I’d like you to consider that dialogue alone is not screenwriting - nor is it even necessary for screenwriting. Screenwriting is character decisions, plot complications, escalating stakes, and shocking reversals. You can do all that in a script without dialogue, believe it or not.

Don’t get me wrong. Dialogue can be amazing. It brings cinema to life in ways that have changed my life. But not one word of dialogue has ever somehow saved a script that otherwise didn’t work.

Silence is a historical and vital part of cinema, in particular. Within it, whole novels were and are still being written. It’s important to accept this is just how the moving image can and does work. While it’s not necessarily right for every story, especially those on television, it’s a vital tool in any filmmaker’s toolbox - and I consider screenwriters to be filmmakers, by the way. Master it, or at least take it seriously enough to not denigrate it when someone else chooses to use it according to their own narrative instincts.

If you want to learn more about silence on screen, consider diving into this 5AM StoryTalk educational supplement - “20 Essential Silent Films You Can Watch for Free on YouTube”.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Great post. I struggle with the note that I shouldn't direct on the page when writing, but it's my instinct to describe images falling past the eye. As I'm deaf, dialogue seems far off. I've lived an entire life without access to dialogue. Subtitles didn't show up on all media until I was late into my thirties.

I read your post expecting you to mention Fury Road at some point. A whole film without even a script, just storyboards! I am reading the book BLOOD, SWEAT & CHROME at the moment. Love it

All of the great movies have stretches of silence that put you right there. Hidden Fortress, My Neighbor Totoro (anything by Hayao Miyazaki), Rear Window, Lawrence of Arabia, especially Omar Sharif's debut, and then my favorite: Blood Simple's 10 minutes of silence where you become an accomplice to murder. About 5 minutes in the audience started looking around to see who else is seeing what they're seeing. One guy kept mumbling "what the fuck? Is the sound off!?" and a few others told him to shut the fuck up.

Personally, dialog sucks. Directors need to direct and actors have got to act to silently convey their experience. Dune II sucked because you really need dialog to understand what's going on. I've resumed watching movies without captions like I did in the 1980s because back then movies were really enjoyable to watch. And some like Stand By Me were memorable, with Wil Wheaton telling Kiefer Sutherland, Suck my dick you cheap dimestore hood." Sutherland's expression was priceless. Enough said!