Christopher Nolan's 'Oppenheimer' Script Blows Up All the Rules

Let's break down how the writer-director challenged form and produced one of the most innovative screenplays of the decade

Regardless of how you feel about Oppenheimer as a film, it’s impossible to ignore how innovative its screenplay is. In fact, it’s so audaciously inventive that many professional screenwriters I know have taken to griping about it, citing it as — and I’m paraphrasing here — “the kind of bullshit only Christopher Nolan could get away with”. This is unusual in my experience because negative opinions about scripts “breaking rules” are typically limited to aspiring and emerging screenwriters who have spent too long drinking the Save the Cat Kool-Aid. As in, they’re so deluded by the rules touted in screenwriting guides and seminars that they’ve become incapable of being challenged by and learning from a script that, in this case, reinvents the wheel (for lack of better words).

My position is that, sure, Oppenheimer’s script might be something that only Nolan pull off - but it also successfully blows up (pun intended) an incredibly rigid form and, in doing so, deserves serious study from screenwriters at all levels. While you might not be able to get away with how Nolan has written the script — and I’ll explain the how in a moment — it might inspire you to think outside the box when writing your own projects.

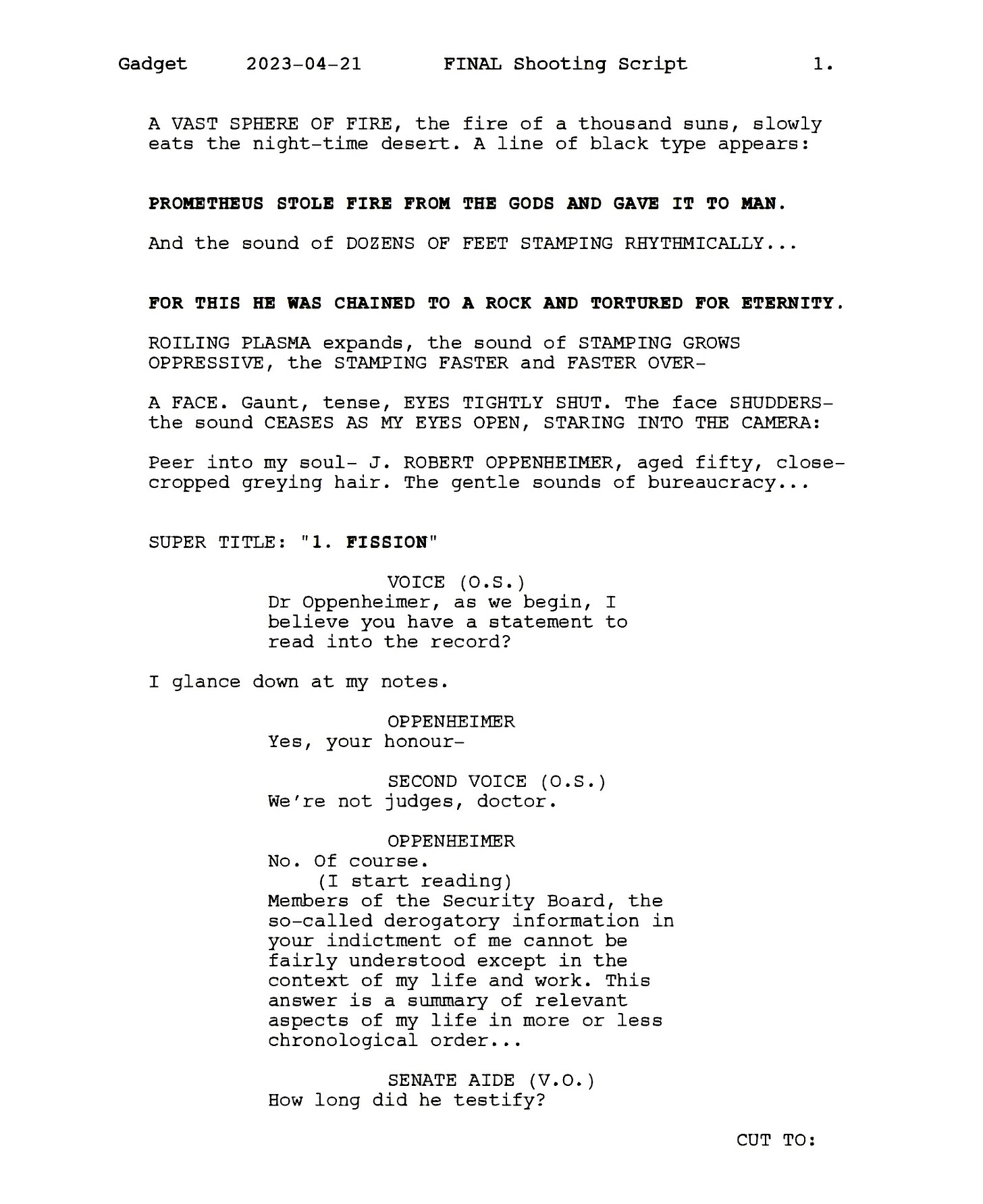

I’m going to dive in by assuming you haven’t read Oppenheimer’s screenplay yet. I’ll provide a link at the end of this article, but for now, check out Page 1.

Notice anything different about the description on this page? If not, read it again.

That’s right: Christopher Nolan wrote Oppenheimer in FIRST PERSON.

Are you serious right now, Cole?

Yes, yes I am.

Instead of using third-person descriptions like, oh, almost every other script in Hollywood history has been written, Nolan decided to take a cue from Frank Sinatra and do it his own way.

To be clear, the whole script isn’t written this way, but the majority of it is.

Why?

Nolan adapted Oppenheimer from the Pulitzer Prize-winning book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. In doing so, he chose to focus on two different characters: J. Robert Oppenheimer (the “father of the atomic bomb”) and his political nemesis Rear Admiral Lewis Strauss. This results in the film being told in two intersecting, non-linear parts: FISSION and FUSION.

FISSION is the story of Oppenheimer before and after the nuking of Japan, exploring his complicated relationship to the bomb and his ultimate character assassination in Washington by Strauss. It’s all shot in color.

FUSION focuses on Strauss’s bid to become the Secretary of Commerce, which instead becomes a trial over what he did to Oppenheimer.

But the most important narrative distinction between these two parts of the film is that FISSION is subjective and FUSION is objective. What I mean by this is that FISSION is told from Oppenheimer’s unreliable perspective. FUSION is presented as fact; while a dramatized version of events, Nolan intends for audiences to unequivocally trust the events presented here.

Two of the many challenges of writing a great screenplay is conveying a tremendous amount of information as economically (and elegantly) as possible and helping the reader see the film you’re describing without using proscriptive directorial language (that would probably distract from the emotional experience of the read anyway).

In setting out to write Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan decided the best way to do that was to use an approach commonplace in fiction - write a character’s singular perspective in the first person. He doesn’t just metaphorically place you in Oppenheimer’s shoes. He drops you right in them and makes you experience the world through his confusing, contradictory, arrogant, terrified, guilty, and even horny POV.

On the Scriptnotes podcast, Nolan told host and fellow screenwriter John August, “It was a big breakthrough for me,” about the decision to use first person. “I knew the structure I wanted. I knew that I wanted to tell the story subjectively. But I knew that I didn’t want to use voiceover.”

But he was also worried that using this technique would amount to “cheating”. It was essential that he could shoot everything he was writing, and so he started off by writing the first act of the film entirely in the conventional third person. Once he was certain it all technically worked, he did a quick swap-out of pronouns and shared it with Jonathan Nolan, who co-wrote numerous films with his brother (as well as created “Person of Interest” and “Westworld”.

“My brother Jonah and I, we were quarantining in a house together,” Nolan told August. “I was writing downstairs. He was writing upstairs. I came up with this idea, and I thought, I’m not going to say anything to him. I’m just going to rewrite what I’ve done and then show him the first act, just say, ‘Look, just gut check, what do you think?’ without drawing any attention to it. He read it and was like, “Yep, don’t know why no one’s done that before, but that works.’ He said to me, ‘You finally found a way to get people to read the stage directions,’ because when you put them in the first person, people value them as information, so they read all of them. Indeed, with this script, people really did read the stage directions in a way that they never have in my other scripts.”

As someone who has been repeatedly told throughout his career that most Hollywood agents and executives will only read dialogue, I can assure you Nolan is not exaggerating.

Now it’s time for you to do some homework. Give the Oppenheimer screenplay a read.

Once you get past how jarring experiencing something new is, consider both how the first-person descriptions draw you in and make you a participant in the story while also emphasizing the untrustworthiness of Oppenheimer as a narrative of his own story. Pay special attention to the death of Jean Tatlock as described by Oppenheimer. He wasn’t there, but we “see” his rapidly shifting interpretation of what happened in a blur of action that culminates in a possible murderer’s leather gloves you might miss if you don’t pay close enough attention.

Whether you admire what Christopher Nolan did with this script or not, take the time to interrogate his motivations and then mull how you might have tackled the same obstacles. More, contemplate how this form-breaking script challenges your own approach to screenwriting. How might it inspire you, whether you deem it a success or failure, to push your own scripts to new and unexpected heights?

Oh, and for the record, I think Oppenheimer is a brilliant film, one that’s only improved upon repeat viewing - and I feel the same about Nolan’s screenplay.

Read the screenplay for Oppenheimer here.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy these other ones from 5AM StoryTalk:

How Do You Like Them Apples?! (or: Why Screenwriting Books Can Be Harmful)

DONALD: Hey, my script's going amazing! Right now I'm working out an Image System. Bob [McKee] calls it an invaluable asset. Because of my multiple personality theme, I've chosen the motif of broken mirrors to show my protagonist's fragmented self. Bob teaches that an Image S…

How to Stop Worrying and Love the Rewrite - Part 1

There’s a saying that most storytellers will hear throughout their lives: writing is rewriting. I’ve never been able to source this quote conclusively — Ernest Hemingway often gets the credit — but I suspect it’s a sentiment that’s been around since at least the time of Aeschylus. That’s because it’s true.

Why Artists Want to Murder You When You Give Them Notes (or: How to Give Artists Better Notes)

I could feel my heart beginning to race. The air pumping out of my lungs burned in my nostrils. My chest tightened as if someone was using their hands like vice grips to crush my ribcage. I’d experienced this so many times before, and yet the panic still surprised me. …

We talked about this, and listened to the Scriptnotes episode. Anyone who is "just" and is grumbling sort of needs to take a seat 'cause Nolan is the one auteur whose films have grossed multiple billions of dollars. That fact alone affords him so leeway.

But, just like Dan Gilroy's NIGHTCRAWLER (written without sluglines), sometimes you can succeed by breaking all the guidelines.

I'm curious to read DUNKIRK after hearing him speak about how many actors turned it down because of the atypical nature of the characters.

"You finally found a way to get people to read the stage directions." 🥲