Why Artists Want to Murder You When You Give Them Notes (or: How to Give Artists Better Notes)

Notes are almost always painful for the artist, which has a lot to do with how bad most of us — including artists — are at giving them

I could feel my heart beginning to race. The air pumping out of my lungs burned in my nostrils. My chest tightened as if someone was using their hands like vice grips to crush my ribcage.

I’d experienced this so many times before, and yet the panic still surprised me. Should I hurl invectives at my laptop screen? Better yet, should I just shatter my laptop against the wall? Logic said to just start typing a pointed response to the script notes I had just been emailed, the kind of message that would utterly destroy the sender’s sense of their own intelligence…except, of course, that wouldn’t actually be logical.

Instead, I slapped my laptop screen shut and stalked away. It was the only smart thing to do, or so I’d learned over the years.

Receiving notes on your creative work — in this case, a screenplay — always provokes this response in me. It likely does for you, too. It’s called fight-or-flight, and we evolved the instinct over millions of years to protect ourselves. Today, it’s a constant liability to our ability to function in our personal and professional lives. In Hollywood, for example, it’s a quick route to being labeled an asshole and drummed out of the film/TV industry altogether.

You would think artists would develop “thicker skin”, as others might call it, but there’s no way to just cast aside a biological instinct more ancient than the human species. Likewise, you would think those who give artists notes – from friends, to talent representatives, to producers and book publishers, to even other artists – would understand this…but they typically don’t.

Let’s talk about why it’s so hard to receive notes on your art and the best way to give notes on someone else’s art. These “rules” — and I hesitate to use that word, because the concept of “rules we must follow” in art irks me — might just save your life. Or at least your project and/or creative future.

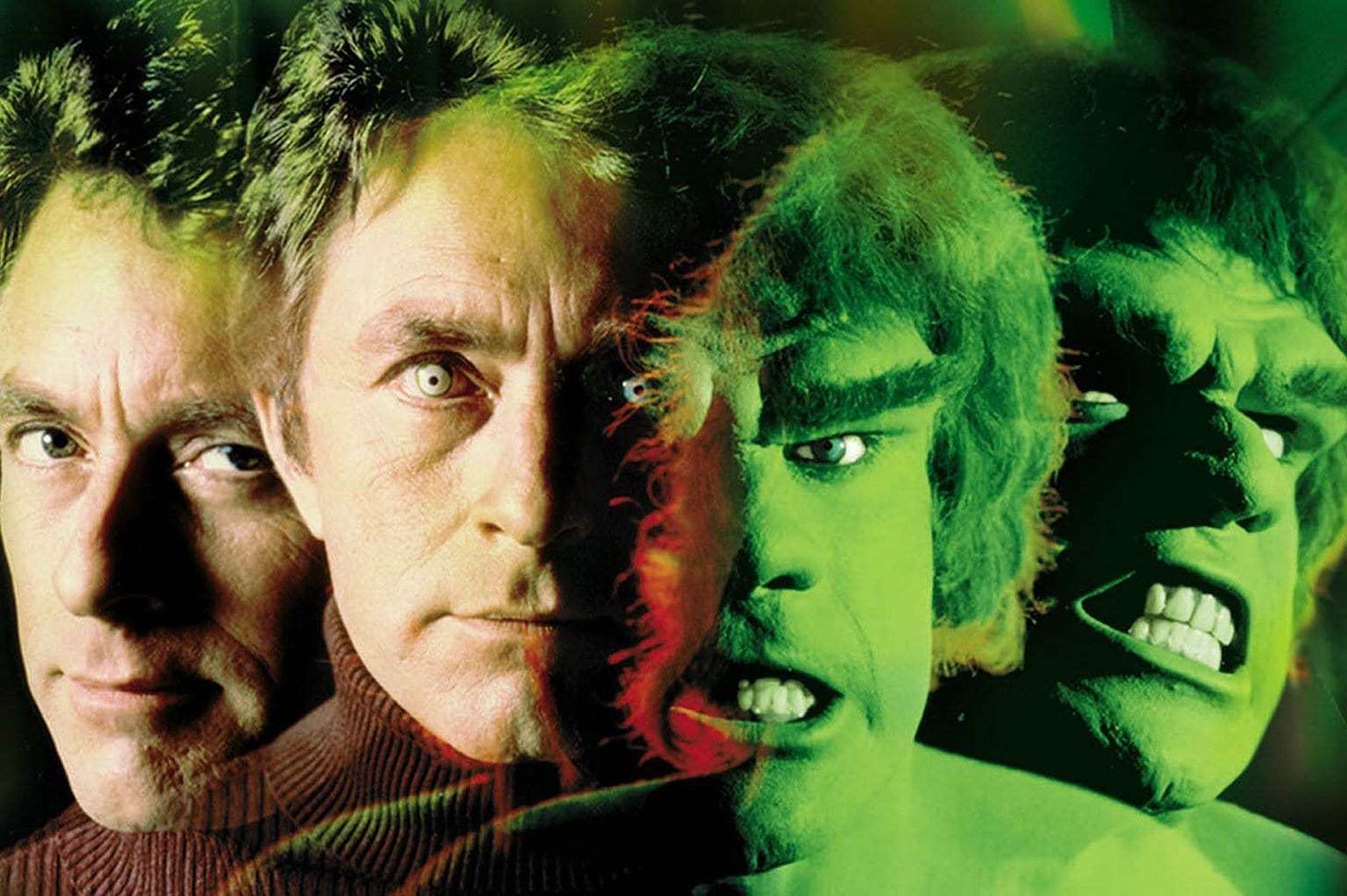

“YOU WOULDN’T LIKE ME WHEN I’M ANGRY”

The fight-or-flight response, also called the acute stress response, is a physiological reaction we have to anything we find terrifying as fuck. Doesn’t matter if it’s a mental threat or a physical one. Doesn’t matter if the threat is to you, someone else, or, in the scenario I just described, my work on a screenplay. When it happens, our sympathetic nervous system stimulates our pituitary and adrenal glands, which in turn releases a whole bunch of fun things like adrenaline, noradrenaline, and cortisol.

The result is increased heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing rate. You can remain in this altered state for twenty to sixty minutes after the perceived threat has passed.

Why is this relevant to art and, in particular, receiving notes on our art?

If you have children, you will understand that anything that threatens them is experienced as a threat against you. About twenty years ago, my father, sister, and I were walking through a parking lot and a car began to reverse out of a parking spot right at us. Before it ran down my sister, the brakes screamed and the car stopped, bumper mere inches from her. My father’s fist dropped like a thunder god’s hammer into the trunk lid, and he roared, “Watch where you’re going, asshole!”

My father did not think about what he was doing in this instance. His brain did it for him before he even understood what was transpiring because the danger to my sister registered as a danger to him. His brain told him murdermurdermurder or you’ll diediedie. And so, he lashed out to protect both of them — but really himself.

Artists create artwork. They pour themselves into these works - their passions, their love and grief and traumas, everything that makes them them. The result is like a child, at least in our unconsciousness. Consequently, notes that criticize these offspring, that pick them apart, that question their identities, are experienced by artists as an attack on themselves. That perceived violence triggers the fight-or-flight response.

HOW DO WE OUTSMART THE FIGHT-OR-FLIGHT RESPONSE AS ARTISTS?

Emotional preparation and learned response.

It took me a long time to begin to understand this, but I have to psych myself up to receive notes. I need to make sure my primitive lizard brain is essentially kept in a cage. I breathe beforehand, I reassure myself, I remind myself about all the notes I’ve received that ultimately led to better scripts, books, or graphic novels. Yes, many of the notes I’ve received ruined projects — including a TV series I created for NBC/Sky — but there is no note, even bad ones, that can be beaten by force of will alone.

As for that learned response I referenced, this one requires more discipline in the moment. You should avoid doing more than having a conversation about notes you disagree with until you’ve walked away from the experience and your body has had the opportunity to recover from the hormones it’s just soaked up like a sponge. Accept it as an axiom before you even walk into the room or get on the phone or sit down across from whomever at the coffee shop. Repeat it to yourself as you listen. Tie a string around your finger to help you remember, if necessary. Basically, respond in such a way as to let the notes-giver know you’ve heard them, but don’t even disagree. And don’t argue. Never argue. You’re not in your right mind, even if you think you are.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t interrogate the note. Bad notes and notes you disagree with both tend to have merit whether you like it or not. They tend to mean something and it’s your job to work out what that meaning is. (My friend screenwriter Meg LeFauve (INSIDE OUT) describes notes “as the symptoms of a disease”, and you can’t just ignore a disease, can you?) But you have no opinion on said note, not until you’ve walked away from the experience and provided yourself a buffer between the hormones and reason.

IS IT BETTER TO GIVE OR RECEIVE…NOTES?

As far as I’m concerned, there are only two types of people in the world who truly enjoy giving notes on another person’s artwork: those who seek to profit from said artwork and narcissists. (Sometimes a person is both, but I’m not going to bother with narcissists here.)

In the first case, this typically means talent representatives and suits such as producers, book editors, and the like. Everything I’m about to say is relevant to you, if you’re one of these people, so I encourage you to consider it along with everything I just wrote about how artists experience notes.

If you don’t fit into the groups I just described, then you are likely a fellow artist, peer, or friend/family member — or some combination of these — who has been asked to provide your opinion, wisdom, and maybe even expertise on someone’s work of art. In other words, you’re giving notes as a favor and, to some degree, that favor is a chore. You could be finally getting around to watching “THE WIRE”, but instead you’re reading my script – which makes me an asshole, I know. Sorry in advance on behalf of all artists.

But here’s the thing, whoever you are, however you’re engaging in a conversation with someone’s art, you took on a responsibility when you either agreed to work with this artist or agreed to provide an opinion on this artist’s work. That’s a burden, I know, but it’s one you accepted. This means the biggest rule when giving notes is: take it seriously or don’t even bother.

HOW TO GIVE NOTES AND NOT ALIENATE ARTISTS

Here’s some advice on how to give notes. This is not a comprehensive list, but I think there’s much here to help you reflect and evolve and, most importantly, offer notes that will actually improve an artist’s work (and preserve their mental health).

Before you engage with the artwork, ask what the artist needs from you. In my case, I might tell a reader that I’m looking for help with the plot and my character arcs. Sometimes it’s as simple as, “I just need to make sure it makes sense.”

In fact, the more questions the better. Going back to my friend Meg LeFauve: “I learned that asking questions can be the best way to give notes. To allow the dreamer in the writer to be present at the table, not just the analyzer.” (Read my interview with her)

Do not give notes on what you want a piece of artwork to be. You are not relevant to this process. The artwork is an expression of the artist and their creative ambitions, not yours.

Start the conversation about the artwork with what works for you, what excites you, what moves you. How did it make you feel? Without this context, all other notes are pretty damn useless, as far as I’m concerned.

As you get into notes about your concerns and confusion, remember your words can destroy an artist’s confidence. They can send them in the wrong direction and undo months or years of work. I say this from personal experience. I’ve abandoned whole projects over bad notes, and it was only when I returned to them years later that I realized how far I’d been led astray by the shitty notes (for example, my debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD came into existence nearly a decade after a terrible response to a core storyline in it convinced me it wasn’t worth pursuing).

If something doesn’t work for you, try to provide examples of why it doesn’t in the context of what does. In the case of my fiction, my book agent wouldn’t tell me, “This chapter sucks.” He’d tell me, “This chapter isn’t moving me like Chapter X did, but I think it needs to because of its importance to the characters’ journeys. Can you look at X and try to identify what’s missing here?”

Your notes are not meant to solve the issue for the artist. They’re meant to illuminate the issue. It’s the artist’s job to come up with their own solution. If they wish to engage you in conversation about that solution, lend a hand.

Whatever you do, give notes on the right project.

Always remember the artist is imperiled by your criticism. They will feel attacked, no matter where they are in their career. If they don’t, they’re missing something in their emotional toolkit, and that’s probably a bigger problem. Be aware of this fight-or-flight response, help the artist navigate it, and be kind if their biology outsmarts their reason.

“I CAN SEE CLEARLY NOW THE RAIN IS GONE”

I opened this newsletter with a description of how I reacted to a notes email from a collaborator not so long ago. It had been a while since I received notes of this kind on my work, and the experience of combing through them, then tearing angrily through, left me discombobulated for all the reasons I’ve laid out about the fight-or-flight response.

After twenty years as a professional writer, fifteen of which I’ve been a professional screenwriter, you would think this would get easier. In some ways, it has, but in others, it certainly hasn’t. I’ve learned how to confront these complicated, intense emotions, how to ignore their siren call to murder, and simply walk away — but it takes an intense amount of discipline on my part.

In this case, I reevaluated the notes I had been emailed the next morning. I found them considerably less distressing without adrenaline pulsing through my body. I was able to contextualize them within the wider development experience, which substantially improved what I thought about them and how my work was potentially received. And lastly, when I sat down with my collaborators, I was able to hear them and provide thoughtful, productive fixes. Nobody was trying to kill me, despite what my lizard brain told me was happening. I wish it hadn’t taken me so long to learn and accept this because I might’ve saved myself a lot of anguish in my creative journey.

If this article and the time I spent on it added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is now available from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. Its paperback will hit shelves on May 25th. You can order it here no matter where you are in the world.

I've been getting notes for 35 years ... on articles, on books, on scripts.

Long ago, I discovered the best approach for me was to imagine I was discussing someone else's project and just listen dispassionate.

Some notes are great, some are stupid, most are useful. Sometimes while getting the note I'll realize the person giving the note has not read the material (more common on the movie business than the book and magazine business.)

Some I accept, some I reject, some I have to accept or decide they aren't worth fighting over. Sometimes the notes are reasonable but they don't resonate with me.

I do my best not to be emotional about the process. It's just words on a page, and sometimes it's better to change those words.

Great piece Cole. People who don’t create work and put themselves on the line have NO IDEA what receiving a “note” is like. I’ve become very suspicious of the whole system of notes and feedback in workshop, etc. But you do a nice job breaking down how, in a professional setting, there’s often no choice but to respond and take it in.