Q&A: 'Inside Out's' Meg LeFauve on Her Complicated ‘Screenwriting Life’

The Oscar-nominated scribe discusses her evolution as an artist and what others can learn from her creative journey

There are few artists in my circle of friends whom I respect more than Meg LeFauve, the screenwriter behind such hits as THE GOOD DINOSAUR1 (2015), INSIDE OUT2 (2015), CAPTAIN MARVEL3 (2019), and, most recently, MY FATHER’S DRAGON4 (2022). It would be easy to attribute my admiration to her wild success, or maybe envy of her body of cinematic work, but what it really comes down to for me is this: Meg is an instinctively, almost obsessively emotional storyteller — at times bordering on spiritual in her approach to characters’ inner-lives — and that is a rare and beautiful thing in an industry that prioritizes visual spectacle over internal pyrotechnics.

I’m not sure if my friend — who is also the co-host of THE SCREENWRITING LIFE podcast — understood what she was getting into when she agreed to let me interview her about screenwriting and what informs the art she creates, but I’m incredibly grateful she allowed me to go so deep into her past, pain, and the fears that all artists must live in tension with. Brace yourselves for an epic conversation that will edify you about craft, encourage you to weaponize your own traumas to become better storytellers, and, perhaps most of all, inspire you to take leaps in your work and life when common sense would argue against it.

COLE HADDON: We’ve known each other for probably a decade now, since right around the time you landed your first job at Pixar. We’ve discussed screenwriting at unbelievable length during that time. Tell me, is it any easier today to sit down in front of a blank page in Final Draft than ten years ago?

MEG LEFAUVE: Yes and no.

No, because every story means facing the unknown again. Even if you come to the page knowing your story, as soon as you start to write, the gulf — between what you envision and what is coming out on the page — widens into the Grand Canyon. So, for me, writing is a series of cliff-jumps…that never get easier. Making it even harder is that I have lost my naivete. That naivete was a blindness that gave me courage. But now I know how high that cliff is, how small the target is. And I’ve fallen, many times, so while I know that fall won’t kill me, I still can feel the shock and pain of some spectacular falls. Every time I consider climbing the cliff again, it all comes back like it happened yesterday. I tell myself this time it will be different, but the thing about creativity is, it’s going to take some falls. It’s just how it works.

CH: Knowing the creative and even emotional peril of all that, what does it take for you to take on a project today?

ML: I must feel so connected to it, or haunted by it, or obsessed with it, that I can’t not do it. That doesn’t mean I know the how of the story, but the why is in me enough to make the climb, to endure the falls, and to hope again — which yes, can sometimes feel like I am making myself purposefully blind.

[Part of the problem is], I also know the highs, the incredible experience of a story you helped birth rippling out into the world. And I know what it feels like to find that click in the whole story or just a scene. It’s addictive, and it keeps me coming back to that blank page. The potential story is there — if I sit my butt down and dare to write badly. It’s also easier because my craft level is higher, simply from quantity of work and from putting my work out there for critique over and over.

As I’ve grown as a writer I can — sometimes — see the blank page the way Sondheim has George Seurat describe it [in SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE] — “White. A blank page or canvas. Is my favorite. So many possibilities…”

CH: What environment do you have to create for yourself to work, or are you someone who could write in a foxhole as bullets whizzed by overhead?

ML: When I was a kid my father would find me reading a book and say, “Meg, I could come in this room and yell ‘fire!’ and you’d sit there and not hear me.” When I get going and I am deeply in, I can write anywhere. But getting in, that takes some quiet and a space of less distraction so I don’t find reasons to not jump off the cliff.

If there is one thing I’ve learned after all these years, it’s that you can’t know the beginning [of a story] until you know the end. So just get there.

CH: And are you a vomit draft kind of writer, keen to just get it out and see what’s working or isn’t, or do you like to rewrite and rewrite scenes as you go until you get to finally type THE END?

ML: Yes, I talk often on my podcast about the “barf draft”. Sometimes, I first find a possible “what is this about”, and from there find a start and an ending for my main character, maybe even do a very loose structure based on that character's movement/transformation. But if in the barf draft, that all changes, I let it change. That’s “the dreamer” [in me] at work. I don’t let myself rewrite as I go. I make myself push forward. If there is one thing I’ve learned after all these years, it’s that you can’t know the beginning until you know the end. So just get there.

CH: I’m going to come back to screenwriting in a moment, but first I’d like to get a better grasp on your backstory, especially since we’re from the same part of the U.S. Who was Meg LeFauve as a child? Who were your parents?

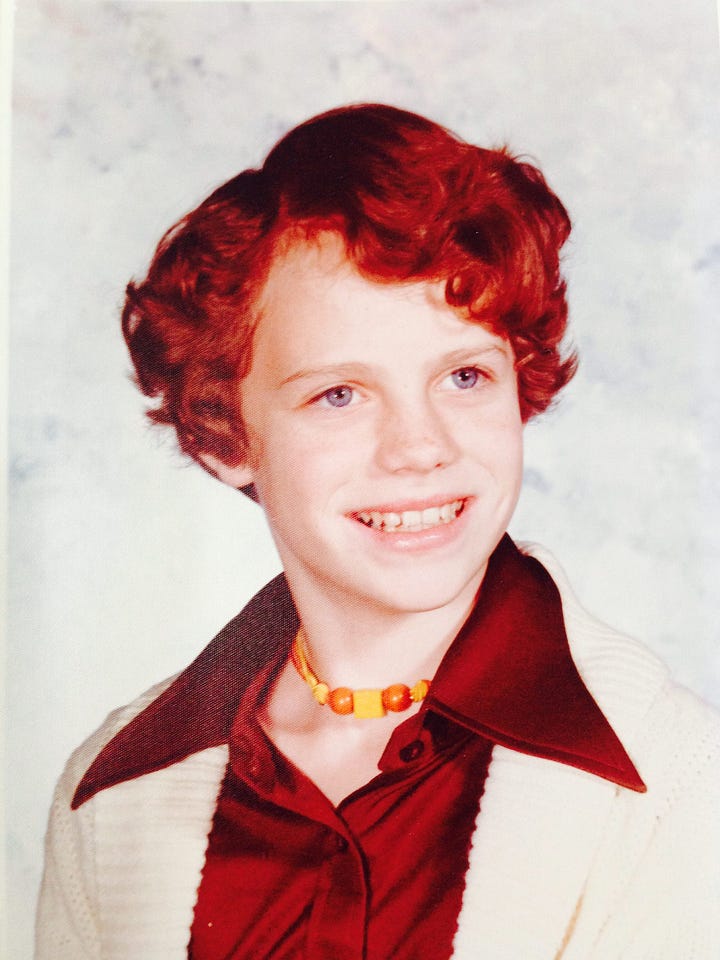

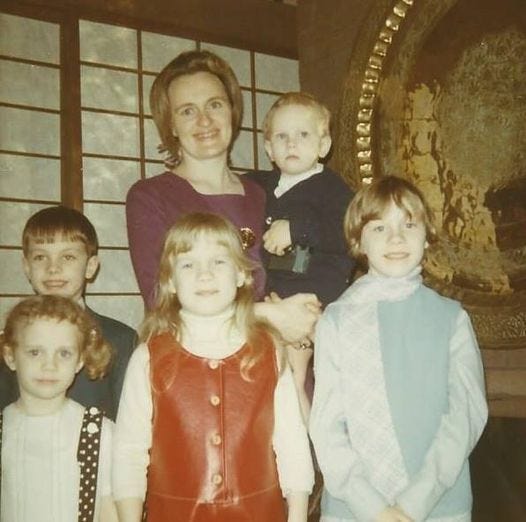

ML: I was born in Warren, Ohio, fourth in a family of five kids. My father was an executive at General Motors, and so my memories of him were coming home after work, making his Manhattan and watching Dan Rather. When he would watch “THE MUPPET SHOW” with me was my favorite time — I loved my dad’s laugh.

CH: What was his name?

ML: Skip LeFauve — named from a song that was popular when he was born, “The Little Skipper”.

CH: And your mother?

ML: Her name was Mary Paul. She was an art teacher who rotated the art in our house with the seasons. She also was a devoted Catholic who joked she had five kids so her odds were better that one of us would be a priest or a nun. I loved the quiet of church, and when I was ten, I was in love with Jesus and was seriously thinking of becoming a nun — Jesus’s wife. Then, I got a crush on a boy in my class, and that was that.

CH: It’s a far more eccentric household than I grew up in outside Detroit, that’s for sure. How did you fit into it?

ML: I learned early, the best way to survive emotional turmoil and confusing signals in a family is to disappear — so I spent my days reading or sometimes the woods, down by the crick, or walking in fields of Queen Anne’s lace.

CH: It sounds ideal.

I remember having friends, but also feeling lonely. I preferred going places in my imagination.

ML: In many ways, it was. I remember running through that field, and swallowing a bug, and staying up all night certain I was dying. And the day my friend and I dumped our bikes at the crick and walked miles away exploring, only to come home to cop cars. Our parents thought we’d been stolen. I was scared and, also, thrilled — that my parents noticed I was gone, and cared enough to call the police.

I remember having friends, but also feeling lonely. I preferred going places in my imagination. I wrote my first story when I was in first grade, in my giant handwriting, about a girl who gets on a plane and falls into a hole in her seat. The end. Of course, if my kid gave me that story I’d investigate why they felt they had to disappear, but back then it was just a cute story.

CH: I always felt as if my family were utterly confused by me. Working class to the bone. Did your family understand you?

ML: My father once said to me, “We have no idea where you came from.”

CH: Oh, I heard that all the time growing up, too.

ML: I was so sensitive and emotional. Now I understand I was an empath picking up all the rumbling unspoken emotions in the house. I just felt like there was something wrong with me. In today’s terms, I think I had social anxiety within my family. I didn’t know how to be.

CH: Were they supportive of your ambitions to dream beyond the Midwest?

ML: My mother came from humble means. She was the “poor girl” at the rich all-girls school, there because her mother was a teacher. My father came from a line of train engineers, and for him going to college was a big deal. Both of my parents were people who aspired.

They never encouraged my young writing attempts, but they also, in their way, respected it.

CH: Tell me more about that.

ML: My mother started an art gallery in Warren, Ohio that is still there (Trumbull Art Gallery). My father made his way up the corporate ladder — my mother hosting business drinks on our back deck — until he was president of Packard Electric and eventually a VP and head of The Saturn Corporation. They never encouraged my young writing attempts, but they also, in their way, respected it. It just wasn’t a discussion. I was going to choose what I wanted to be, and then work my ass off to get it. It was the work your ass off that was important to them — because that is what they had done.

CH: What about college? What was that like for you?

ML: At Syracuse, I was a dual major, screenwriting and English.

CH: I didn’t realize you got a screenwriting degree, that you had that specific itch so early.

ML: My father didn’t know what a screenwriting major meant. There are advantages to being the fourth child — your parents are too tired to argue.

CH: I’m curious about when, precisely, your mother’s health changed in your story.

ML: I spent senior year spring break in London with my friend Debbie, and met a boy from South Africa. After graduation I went back to London to be with him, worked as a temp and lived in a boarding house — three kids to a room — full of twenty-somethings from all over the world. But after a year of this grand adventure of hanging out, my mother was ill with early onset Alzheimer’s, so I returned home. My father didn’t want me to spend my youth caring for my mother, told me to go live my life. When she was lucid, my mother, too, told me to go. I did, mostly because I was afraid and overwhelmed by her disease.

CH: I always find it remarkable how unprepared I was in early adulthood to deal with my parents’ fragility. I think it frightened me so much it created a barrier at times, so I understand what that must have felt like. How did you escape it?

ML: Looking back, I think that some survival part of my brain [shifted] away from my mother’s creativity towards my father’s logic. So, I moved to New York City and became an advertising executive. This was in the days before sexual harassment was a concept, so there are many stories to tell.

I was working my way up the ladder when, one day, I was in an interview to be promoted, and while I did my schtick on the outside, inside my head was screaming, “Don’t give me this job!”

CH: This is where you met Joe, isn’t it? (Note for reader’s: Meg’s husband Joe Forte is also an artist, as well as a good friend of mine.)

ML: Yes, I met him at the ad agency, and we had a “secret” affair because dating between account execs and creatives was frowned upon.

I was working my way up the ladder when, one day, I was in an interview to be promoted, and while I did my schtick on the outside, inside my head was screaming, “Don’t give me this job!” It was so loud, I had to listen to it.

My friend from Syracuse, Chris Andrews, had gone out to ICM [in Los Angeles], and called to tell me I should come out there. It was a nutty idea to even consider — I’d be going backwards from being an exec to being an assistant. I didn’t want to be an agent, but I also knew that being in Hollywood was closer to my heart then advertising. Working at an agency would teach me the business, and it was a job. So, I jumped off the cliff — left New York, my friends, Joe — and moved to LA. Thank goodness Joe also came about six months later.

CH: After ICM, you headed to Jodie Foster’s Egg Pictures. I have to know how the hell you became a producer, or rather why. I try to imagine you producing one of my projects, and I’m afflicted with visions of being wildly supported both emotionally and creatively.

ML: I became a producer because I was too chicken-shit to be a writer. I see that now, at that time, I was being a “shadow artist”. I was unconsciously trying to be around creativity, to work through the creative people, but not stand in the harsh spotlight myself — where failure could be personal and public. I had my father’s exec brain and knew, from years of living with him, how to approach the business side of it. And I had my mother’s artist brain, so I understood how to talk to writers. And I loved figuring out why stories didn’t work. I still do. I’m a story junkie. So, to work with the likes of Jane Anderson and Keith Gordon, and help them tell their stories — it was an honor and I learned so much. But there were some aspects of that job that were not my truth. It took me years to really know that.

CH: What about it prepared you to become the writer you are today?

ML: First, just by reading the sheer number of scripts I did. Five to ten a week, if not more. Reading that much, it becomes like music, it seeps into you. I also understand what actors need in a role, what directors need in a story, what execs need. And how all those things better be aligned. I understand how something is shot from being on set producing films. I understand how stories and scenes need to have a rhythm, and if they don’t the editor will make one. All of this had an effect on me as a writer. Not in any way that I consciously think of when I am writing, but more like the music of it.

After ten years that voice returned, telling me to go. To jump. So I did it, I told Jodie I was going to go write.

CH: I tend to think of producers who become writers — and I don’t mean the ones who flirt with it, the ones who just go for it — as having experienced a kind of religious conversion. You decide one day you’re not going to be Mormon anymore, it’s time to go out into the world as a Hindu or Muslim or, I don’t know, a Confucian. What precipitated your spiritual conversion?

ML: After ten years that voice returned, telling me to go. To jump. Plus, I was complaining a lot at home about not being the creative at the table, and Joe told me to “shit or get off the pot.” It was the greatest act of love to tell me that! I knew I didn’t want to be eighty, and wonder what I could have created. So I did it, I told Jodie I was going to go write. She was very supportive.

CH: So, what happened next?

ML: I went from being a somebody in Hollywood to a big fat nobody. It’s hard on your ego.

CH: I can imagine.

ML: And learning to write at thirty-seven is a bruising ego trip, too. But I did it. I wrote all those crappy drafts and learned my craft.

CH: What was your biggest misunderstanding about the craft that transitioning from a producer to a screenwriter revealed to you?

ML: There’s really no way to understand the depth of the challenge of writing — and the high — without doing it. Because the writing lives in a different part of your brain. You can analyze and develop and talk about stories for years, but when you sit down to write, you are going to have to use the right side of your brain, be the dreamer, and that’s just a whole different experience — and challenge. When I left producing I could “play ball” at an NBA level. But as a writer, I was, at best, in high school ball, second string. Doesn’t mean I didn’t have talent or know how or “a spark”, but being the dreamer is accessing parts of yourself that the talker/analyzer you would rather not. Writing is a transformative act. You have to face yourself over and over.

CH: You’ve talked about notes a lot on your podcast THE SCREENWRITING LIFE, both giving and receiving them. I’m curious what becoming a writer taught you about them?

ML: I learned why notes can be so confusing, demoralizing and unhelpful. I gave notes a thousand times — and I think I did it well — but after becoming a writer, I learned that asking questions can be the best way to give notes. To allow the dreamer in the writer to be present at the table, not just the analyzer.

I also understand now that when receiving notes, some part of the writer brain goes into survival brain. It takes practice to stay present to the notes in real time, and so it all must be written down — recorded — so you can go back later and really hear it.

I also assumed as a producer that there were “genius writers” out there who were just born that good. I now understand the intense work it takes everyone — every time.

Isn’t fear is a component of creativity? It means you are “out there” on your creative edge, which is where you have to be to do great work.

CH: Fear handicaps most of our lives, but it seems to have a real presence in much of this conversation. Resonant might be the right word to describe it. At the same time, as often as you ran away or avoided or stood in your own way, you also took a great number of daring leaps when it would’ve been easier not to. Can you discuss what role you think fear plays in your life as an artist today, how it hinders and/or helps you?

ML: Yikes, fear as a resonant presence in my life? That sounds awful. But I guess it’s true. Since I’ve been a kid, this fear and anxiety has travelled with me. But I have tried to never let it define me. And it doesn’t always handicap me. Instead, I like to see it as the artist in me — “a sensitive soul” as my mother used to describe me.

Because isn’t fear is a component of creativity? It means you are “out there” on your creative edge, which is where you have to be to do great work.

CH: Absolutely.

ML: At the same time, when I am deeply in a story, fighting for the character and their story, the fear must take a back seat. And sometimes that ride with the character can be thrilling to the point I forget the fear. Then read my pages over the next day and…hello, old friend.

You would think that the longer you are in the business of writing/storytelling, the less the fear gets, and that’s true to a point, but, honestly, it can get more intense because I know how far off the ground I am.

CH: I’m curious if you’ve learned to weaponized your fear at all in your process.

ML: The only way I can think that I may have weaponized my fear is turning it to anger or determination. When someone tells me “you can’t,” I tend to have this steel rise in me that replies, “Really? I can’t? Let’s see…” When I lost the Academy Award, the first thought in my head was, “I’m getting back here.” If I do or don’t is pretty irrelevant. It’s the drive I need. Though awards and accolades really aren’t the best driver because the shadow side of that motivation is tons and tons of fear — the fear of being “good enough”. And getting your validation from outside yourself never works. The better antidote to fear is passion for your character. Your character chose you to tell their story, and if you don’t sit down, push through the fear, and tell their story — they will never exist. That passion is the best motivator and fear fighter I have.

The better antidote to fear is passion for your character. Your character chose you to tell their story, and if you don’t sit down, push through the fear, and tell their story — they will never exist.

CH: That’s a beautiful sentiment, Meg. As a screenwriter, what are you most afraid of at this very moment?

ML: Not getting to tell stories that people will see. It’s so out of my hands as a writer if something “gets made”. Or how it gets made. Or what it is made into. And, of course, as soon as I think of someone actually “seeing my story”, then the anxiety whirls around and says “and they will hate it” — ha! It’s why I always have to go back to my own private process. What do I like? What story do I want to tell? What would be fun? What would be delightful? That’s where fear and anxiety can’t go — because joy is their opposite.

CH: We’ve discussed elsewhere the experience of working with Pixar, the incredibly positive energy of that collaborative environment, but also the brutality that comes with developing ideas, scenes, even whole narrative threads that can be casually murdered the next moment because they don’t justify themselves enough in the story everyone is trying to tell. What has this process taught you about self-editing when you’re on your own, working on other projects, tackling a rewrite?

ML: Well, I’d never say that anything is “casually murdered” at Pixar. There is no place more respectful of the artistic process and what they are asking of their creatives. And isn’t that “murder” the process of any creative act? Don’t we all as artists have to develop the skill to let go of what doesn’t work, to see beyond what we have, to what could be? To push and strive, to constantly ask “is this the best story? Best version? Most authentic and true story I can tell?”

CH: I couldn’t agree more.

“Notes” are telling you the symptoms of a disease. You have to go down to the root of the story to make any real changes.

ML: What I think a lot of emerging writers don’t understand about rewriting is that every time you rewrite — not modifying, not dabbling — you are truly recreating. I tell students that when I do a rewrite, I go back to the story engine and re-card the movie. I don’t open that old script. I start all over with an empty document. Emerging writers are stunned by that. But how else could it be?

“Notes” are telling you the symptoms of a disease. You have to go down to the root of the story to make any real changes. If you don’t, you’ll just get new symptoms. Plus, every time you get notes, shine a harsh light on your work, you are discovering what story it is that you are trying to tell. I am not saying this is an easy process, but it is the process of art. But I also acknowledge that every artist must find their own process.

CH: Your storytelling has embraced emotional and psychological components, especially INSIDE OUT — which literally goes into the confused mind of a child coming of age. How much of yourself to inject into your work and to what degree do you find you’ve used your screenwriting to process your own complicated emotions and traumas?

ML: I don’t know how to write without putting myself into it. On the podcast, we talk about our “lava”, the stuff of our soul and life experience that makes us vulnerable and also makes us who we are. That doesn’t mean that I don’t, as a writer, have to focus on the director, because ultimately it is the director’s story that we are tasked with birthing. But if I am doing my job right, and helping the director plumb the depths of themselves and what they want to say with the story, we will hit something that reflects the human condition — that anyone can feel and relate to.

So, it is Pete Docter who is the genius who wanted to explore how “Sadness” connects us, but I still had to be brave and allow my own “Sadness” — and connection — come into it. I have to dig up with it felt like to be an eleven-year-old girl, and what, like Joy, it feels like to be a parent who wants their kid to be happy.

The scene [in INSIDE OUT] when Riley’s Mom says to her “thanks for being our happy girl” was on the chopping block many times in development because there was a concern that it made Mom unlikeable. But every parent has said this to their child. Please be happy. And the scene when Riley comes home at the end of the film, and says to her parents, “You want me to be happy, but I’m not” — I didn’t realize until I saw the scene in boards that this is what I wanted to say to my parents. I wasn’t brave enough to do that, but Riley is.

Perhaps that’s a fantasy of the child inside of me, that if I had spoken my truth, I could have healed some of my family.

It was important to me that when Riley says this, that it unlocks her parents, that because of her authenticity, they open to their own sadness and loss. So, the family can be deeply together in that moment. Perhaps that’s a fantasy of the child inside of me, that if I had spoken my truth, I could have healed some of my family. It didn’t happen that way, but that’s why we are storytellers, so we can work it out, show a path for others.

CH: Christ, Meg, now I’m crying. Okay, so your parents taught you to work your ass off above all else. Do you feel like you’ve met their expectations at this point enough to slow down, or is there a part of you that’s worried that will never be possible?

ML: Neither of them lived to know me as a writer, but I had two experiences with my father when I was a film producer. One film I produced in my early-thirties I watched with him on TV, and, as the film’s very, very sad ending drew to a close, my father looked at me and said, “Why would someone want to make that? It’s so sad.” I was gutted.

A few months later, I was lucky enough to be able to walk down the Emmy red carpet with him when I was nominated as a producer for that same film. He was proud, but also overwhelmed by the yelling paparazzi (because we were walking with Jodie Foster). It was a fun experience to have with my father, but honestly, not an emotionally intimate one. That happened for me when I brought the next film I produced — DANGEROUS LIVES OF ALTAR BOYS — to his hometown film festival. As we were leaving the theater a man approached me, agitated, upset at the film. He started to go after me a bit. I could feel my father next to me, waiting to see what I would do.

But I didn’t respond to this verbally aggressive audience member the way my father would have. Or how my mother would have. I responded how I naturally do. I asked the man questions about what upset him, I told him what we, as creators of the film, intended and I told him, “It’s okay if you didn’t like it. Not every movie is for everybody,” and I walked away. I will never forget the smile on my father’s face. The pride.

CH: Final question. You’re co-host of THE SCREENWRITING LIFE podcast. What has more than a decade as a screenwriter taught you about life?

ML: There’s the writing, the artistry of screenwriting, and there’s the business of it. Both have taught me so much…

It’s a long game.

Choosing to be an artist means choosing to be vulnerable

It’s okay if everyone doesn’t get you, even though your head will tell you everyone must love you.

When you are in the right “pond” doing the thing you are meant to do — you can feel the difference. My worst day of writing is still better than my best day of producing.

How strong I can be.

That the universe can dream bigger than I can. But it asks for commitment and risk in return. And to stay open and trust.

That it’s all about connection. Stories are about connecting with others. And the business is about what connections you can make. Choose wisely.

In life and this business there are predators, and there are people without much sense, and there are people playing a game I don’t like playing — and aren’t good at. And there are people who love stories and have the best intentions and are here for all the right reasons. Find your people.

There usually is something unexpected coming — probably a bunch of unexpected things coming. Some thrilling, some bone chilling. It’s the way of creativity and business. Don’t take it personally — which I always do anyway.

I still believe most people are doing the best they can in their own fucked-up psychology and belief system.

Everyone believes they are the hero of the story. Know that when you are working with them, and especially when you disagree with them.

Often what is behind the notes you get — or what people are saying to you — is really, “I’m scared.”

Victim power is very enticing. And limiting. And doesn’t make for great stories.

Go for what lights you up — what you feel in your gut. Going for the “money” or the business strategy, or what other people want you to be, often isn’t going to work out long-term.

You can change your mind about your story and your life.

Just because you are good at something, doesn’t mean you have to do it.

People’s view of you is none of your business. Because it’s more about them than you.

You can always learn, you can always open up to your blind spots, you can always confront your own limitations.

Being busy is an addiction — and a high form of laziness. But I can’t quite seem to stop doing it.

You can’t know what projects will make it, to the screen or to people’s hearts. All you can do is be true to the story you are trying to tell. And let the rest go.

The more you do anything, the better you will get. Which sounds obvious, but it often isn’t. We all want to be “great” immediately. That isn’t how “greatness” works.

Anything that takes craft and artistry will take years to learn — so chill out and just start.

Everyone sucks at writing at first. Everyone.

You’re scared, anxious, unsure — do it anyway.

You can find Meg’s podcast THE SCREENWRITING LIFE here, which offers a profoundly human approach to craft. As much emotional support as it is “rules”, tips, and the like.

If this article and the time I spent on it added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is now available from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. Its paperback will hit shelves on May 25th. You can order it here no matter where you are in the world.

GOOD DINOSAUR was written by Meg LeFauve with story by Peter Sohn, Erik Benson, Meg LeFauve, Kelsey Mann, and Bob Peterson

INSIDE OUT was written by Meg LeFauve, Pete Docter, and Josh Cooley with story by Pete Docter and Ronnie del Carmen

CAPTAIN MARVEL was written by Anna Boden, Ryan Fleck, and Geneva Robertson-Dworet with story by Meg LeFauve, Nicole Perlman, Anna Boden, Ryan Fleck, and Geneva Robertson-Dworet

MY FATHER’S DRAGON was written by Meg LeFauve with story by Meg LeFauve and John Morgan