How Do You Like Them Apples?! (or: Why Screenwriting Books Can Be Harmful)

While my take might be controversial to some, let's discuss why I think many how-to guides have helped break Hollywood and kneecapped countless potential screenwriting careers

DONALD: Hey, my script's going amazing! Right now I'm working out an Image System. Bob [McKee] calls it an invaluable asset. Because of my multiple personality theme, I've chosen the motif of broken mirrors to show my protagonist's fragmented self. Bob teaches that an Image System greatly increases the complexity of an aesthetic emotion.

KAUFMAN: You sound like you're in a cult.

-ADAPTATION (2002)

There are some great screenwriting books (and websites) out there, don’t get me wrong. But in general, I find they’re only useful for explaining rudimentary “rules” about things like formatting, providing a useful lexicon of script terms you should know, and as doorstops. There’s even a decent argument some have even contributed to the downfall of quality in cinematic storytelling in the 21st century. However controversial these positions might be to some, I’m absolutely confident most of these so-called guides only hinder an aspiring screenwriter’s chances of breaking into Hollywood. Let me explain…

Screenwriting Books Are Not Bibles

Again, I do not think all screenwriting books are filled with nonsense. In fact, many have ideas worth interrogating and integrating into your own creative toolbox. But something often occurs in the act of monetizing one’s alleged expertise for how-to guides that quickly reduces a complicated craft and art form to a paint-by-numbers exercise for many. Worse, they’re often mistaken as potential get-rich schemes by others who can’t accept how much work screenwriting — or rather, becoming any good at it — actually takes.

What have I personally taken from these guides?

Basic outlining ideas, for one. But you can find those online.

Formatting instructions, for another. But you can also find those online. More, screenwriting programs like Final Draft and Fade In — required tools of the trade — spoon-feed these to you these days.

There are a lot of arguments in them about how to plot, or craft scenes, or develop characters, sure, but these processes are largely subjective and evolve from much personal experimentation. These necessary skills are also almost always better enhanced by — in no specific order — reading dramaturgy books, watching plays, watching films, going right to the source (for example, read Joseph Campbell’s THE HERO WITH A THOUSAND FACES to understand his concept of “the hero’s quest”), reading academic film criticism, listening to DVD commentaries, listening to podcasts in which actual filmmakers debate their craft (SCRIPTNOTES or THE SCREENWRITING LIFE, reading books about filmmakers by filmmakers (François Truffaut’s HITCHCOCK/TRUFFAUT comes to mind), and, as I will repeat over and over here, reading produced scripts.

There’s also another problem with all of these (sorry) conventional screenwriting texts. They’re informed by a slow-to-evolve narrative tradition that remains largely American-centric and, in the past thirty years, primarily focused on satisfying corporate masters by appealing to broader and broader audiences. This means a push toward the middle, toward inoffensive mediocrity.

I mean, try to imagine the savage brilliance of 1970s American cinema or the independent US cinema revolution of the nineties being derived from these screenwriting books. Neither would’ve been possible, and with the decline of that innovation, that daring reinvention of the craft, so, too, has Americans’ relationship to the moviegoing experience declined.

I think a quicker way to say all this is: what these screenwriting books rarely teach is the possibility that all their “rules” are wrong or even potentially damaging to the originality of work, the potential for the art form to grow, and the endurability of American cinema. Or that they typically produce scripts that impress nobody, damaging an aspiring screenwriter’s chances of earning any interest in their work or acquiring an agent/manager — but more on that in a moment.

“Your sad devotion to that ancient religion has not helped you conjure up a good script.”

On one of my earliest jobs, I turned in a draft that included flashbacks. Now, there are dozens of ways to use flashbacks. I’ve seen it done well and I’ve also seen it done poorly (sometimes by me). In this specific case, I think it was done…competently. I got better. But the point of this anecdote is, the development executive I was working with — who was very young and as new to their career as I was — worried I might have done it incorrectly. Here, they turned and fetched a popular screenwriting book from the shelf behind them to determine if I knew what I was doing.

Process that.

The person giving me notes on my script, helping to influence its potential future — and my own — required a popular screenwriting guide to tell them whether I was correctly writing the screenplay I had just been paid a lot of money to, you know, write.

This has always struck me as funny, but, to be fair, it’s very common. So common, in fact, that Robert Altman poked fun at the devolving quality of the development process by placing Viki King’s HOW TO WRITE A MOVIE IN 21 DAYS in the desk drawer of Griffin Mill in THE PLAYER way back in 1992. By the way, what a spectacularly stupid fast-food approach to screenwriting. Scripts are not industrialized products meant to be churned out by way of lazy shortcuts.

Anyways, back to my anecdote. In the case of my exec, the book they relied upon for their understanding of screenwriting was none other than Blake Snyder’s SAVE THE CAT! THE LAST BOOK ON SCREENWRITING YOU'LL EVER NEED.

Here’s a description of it I came across online from Studiobinder:

Snyder’s book effectively breaks down the genres, and the beats that every good script should follow. It essentially creates a screenplay template that helps writers drag and drop ideas.

In reality, this book is pernicious and filled with infantile nonsense. While there are certainly many arguments within it that hold some merit, it reduces cinema to something I abhor and could be cited as the font from which countless by-the-books, soulless, mundane films — especially IP-driven ones — have sprung over the past decade and a half. I’m not alone either; while I haven’t quizzed every professional screenwriter I know, I have never met one who had anything positive to say about it without laying out numerous critical caveats first.

These days, I wonder if there’s much of a difference between what it argues and what ChatGPT does. After all, remember, children: SAVE THE CAT! provides “a screenplay template that helps writers drag and drop ideas.” You don’t even have to think, just follow the prompts.

And yet this screenwriting book remains a bestseller and has now even spawned a spin-off about how to write terrible novels. This is because, at least from my experience, aspiring and emerging screenwriters turn to it as if it’s a get-thin-quick diet book rather than some rudimentary ideas about commercial screenwriting to be cautiously absorbed and measured against knowledge gained elsewhere through dedicated study and experimentation. Worse, I think many who represent and produce screenplays — agents and the Griffin Mills in Altman’s Hollywood satire — have relied too heavily upon it as a source of expedient expertise. This is reflected in how they now react to screenplays they read and how they ask screenwriters to develop their scripts…and, of course, in what we find on our movie screens.

Screenwriters are Not Generative AI Programs

Screenwriting books provide ideas that a curious human sponge should suck up, sure, but they shouldn’t be treated as immutable laws of cinema. Anyone with time could write a counter-book to SAVE THE CAT!, for example, easily providing numerous examples of why doing the opposite of what Snyder suggests can also produce successful, often far more iconic — in other words, more enduring — films. (See Quentin Tarantino and Stanley Kubrick, for example).

Our jobs as artists — in this case, screenwriters — is not to follow such reductive formulas like they’re rainbows leading us to great big pots of sweet-ass gold. It’s to take the formula and challenge it, discover its limits, and go beyond those limits when necessary. It’s to disrupt, to innovate, to express something in some new way that might impact hearts and change how those who follow us create.

If all you’re doing is filling in blanks in an outline someone else told you to print out and follow, then, again, what’s the difference between you and ChatGPT?

“I want to break free-hee! I want to break freeee!”

Your skills as a storyteller will be derived as much from understanding the “rules” as how you break them. These so-called rules” I’ve argued here and elsewhere, are tools to use against the audience’s expectations. They’re there for you to use to your advantage, I mean — not as a cage to handicap your creativity and narrative ambitions.

If at any point in your journey, even as an aspiring screenwriter, you say something like, “Only successful screenwriters get to do crazy shit like that in their screenplays. New writers like me have to follow the rules if we want to get signed,” then I worry you’re unlikely to ever have a future as a screenwriter.

You might get signed, sure, you might even sign something, but sooner or later, the industry will recognize you have nothing of value, nothing original, to contribute. There are a hundred more blank-happy hacks waiting to take your job, so you must be better than any screenwriting guide you can find on any shelf.

But the thing is, I don’t think you’ll even get signed.

My friend Franklin Leonard founded THE BLACK LIST, which celebrates the best unproduced screenplays in Hollywood every year. Read through these and, more often than not, you will find the scripts succeeded because they broke several rules. Because they innovated. Because they did things nobody else thought to do with similar stories. Countless careers were launched by scripts from “first-time screenwriters” (not really, this was just the script that got them attention) who dared. Who took risks. In other words, who didn’t conform.

Ask yourself: how do you stand out if nobody can tell the difference between your script and the rest of the digital pile of PDF’s building up in their inbox?

“How do you like them apples?!”

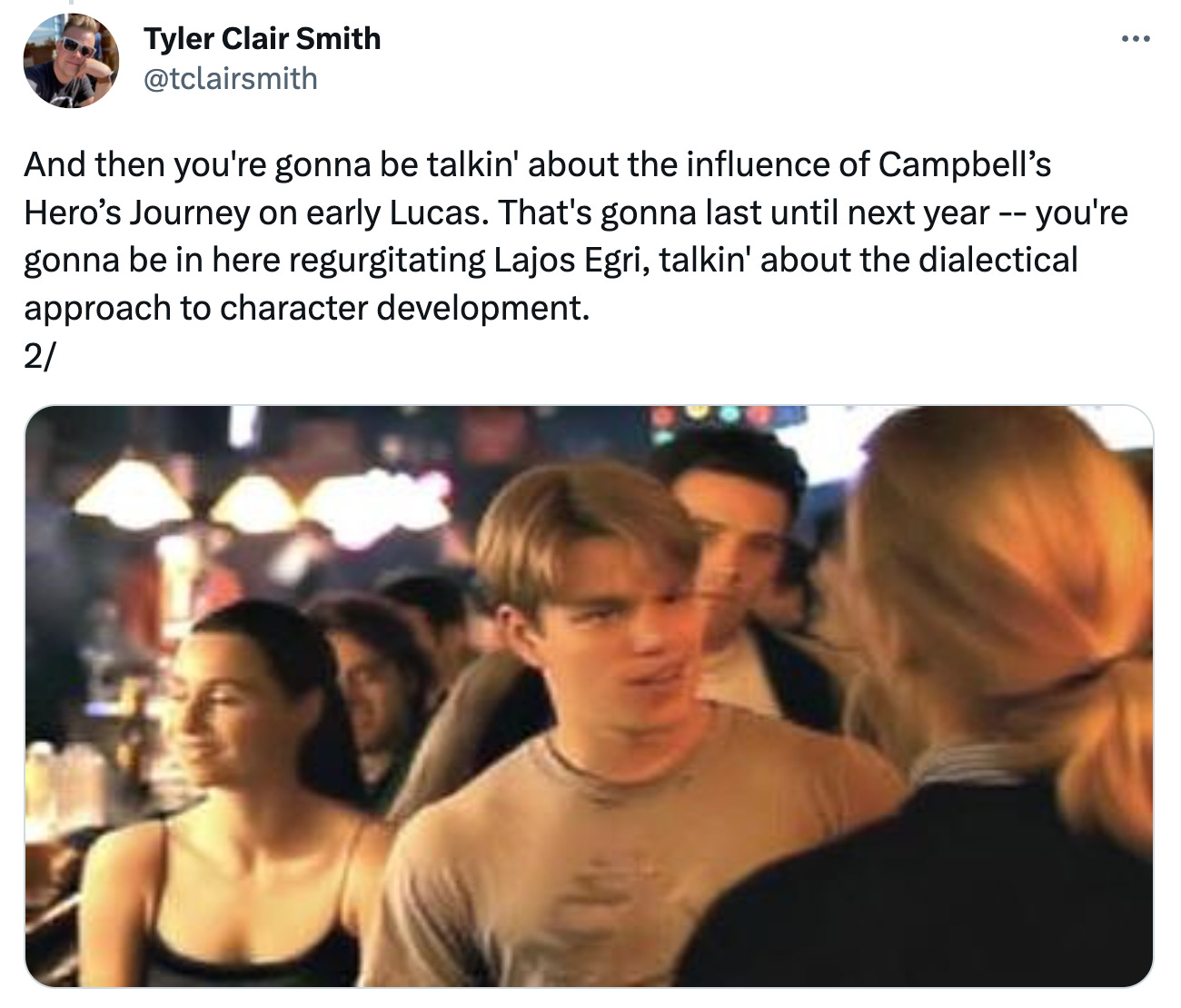

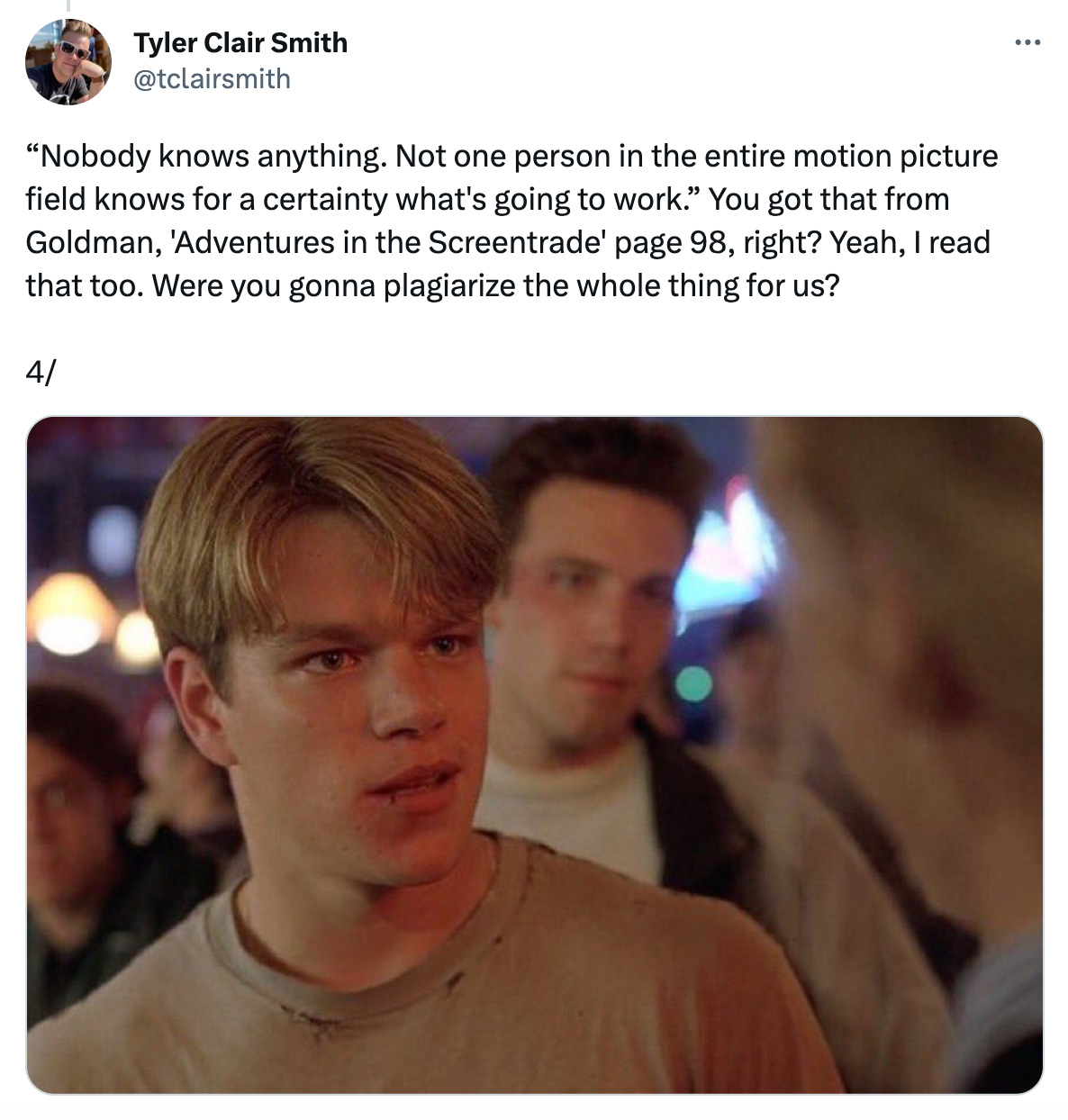

Which brings me to a fantastic Twitter thread from Tyler Clair Smith (INCARNATION) I stumbled across this week. It turns out I wasn’t alone, as my peer Scott Myers at GO INTO THE STORY (the official screenwriting blog of the Black List) also wrote about this thread as a way to discuss “parallel development” since another screenwriter, Dan Plagens, had tweeted something similar at just about the same time. Parallel development is a very real thing all screenwriters contend with, in which similar ideas evolve from different writers at the same time — kind of like this essay — but, in this case, I’m far more interested in how Smith’s thread uses an iconic scene in GOOD WILL HUNTING to satirize the deification of screenwriting books and the elevation of their writers to guru status. Here it is:

Don’t Be the Guy with the Pony Tail

I asked Tyler what inspired him to compose this Twitter thread, and this is what he emailed back:

I have no beef with Blake Snyder or Robert Mckee – much less Lajos Egri. There’s a reason my silly thread cites those three; they’ve taught me most of what I know about structuring a screenplay. The methodology and the gurus themselves don’t really deserve our ire. But their acolytes? Hoo boy.

Discovering how screenplays work can feel like you’ve stumbled upon a gnostic secret. You’ve been initiated into the cosmic mystery. It’s revelatory; like Neo, you’ve seen THE MATRIX. On movie night, you whisper to your partner the arcane mysteries (“This is the second pinch point!”). That’s cool. Understanding the inscrutable is intoxicating. Get drunk — it’s fun!

But that knowledge can be weaponized — often by those who have only recently been initiated into the mystery. I’ve seen professionals offer advice in good faith, only to be shouted down by neophytes who are proud for completing the second draft of their first screenplay.

This, I should say, is something I have experienced frequently when attempting to offer advice and/or insight in various screenwriting groups on social media. Those with no experience except screenwriting books on their shelves leap headfirst into conversations to rudely declare how little I know because (insert random rule they’ve been told).

No book can provide you so much knowledge on screenwriting that you can purport to be an expert on the subject. There is no quick route to that kind of confidence either.

There Are No Shortcuts in Screenwriting

Expertise comes from years of submission to your craft, as I have tried to explain here. Even when you’ve “made it”, you’re still learning. You never stop learning. I’ve written close to a hundred features and/or teleplays, I’ve read hundreds of scripts, I’ve watched more than 10,000 films (I know, because I keep track!), I’ve read thousands of fiction and non-fiction books, I’ve studied art in all its forms and literally traveled to some countries just to visit their museums…and I’m still learning.

When I stop learning, when I think I know all the answers, when I start telling you what all the answers are, I will have nothing left to say. That’s why I call my essays here “conversations”. We’re having a chat, we’re talking about our experiences, we’re growing together.

Read your screenwriting books and listen to the podcasts so many people love and quote, steal the scraps in them that make sense to who you are as an artist, and then leave them behind. Because I promise you, the people currently making a living in the career you want for yourself so badly already have.

In conclusion: do you want to read my how-to guide when it comes to becoming a professional screenwriter? Well, here you go:

Read scripts, read scripts, read scripts.

Watch films, watch films, watch films.

Write, write, fucking write.

It’s a difficult thing to accept, especially when ambition and dreams leave you impatient, but the artist’s life is not a sprint. It’s a marathon…that only really starts after a lot of training and, counter-intuitively, doesn’t have a finish line.

Follow Tyler Clair Smith and Dan Plagen on Twitter.

Follow Scott Myers on Twitter and subscribe to him at Medium for some brilliant insights on craft and regular screenwriting resources. He has a new screenwriting book out called THE PROTAGONIST’S JOURNEY: AN INTRODUCTION TO CHARACTER-DRIVEN SCREENWRITING AND STORYTELLING I’m genuinely excited about. I haven’t read it yet, but I’m confident it will be filled with a lot of useful wisdom. Scott largely instructs from a place of example, of guidance, of helping you ask your own questions — which is how it should be done.

If this article added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here no matter where you are in the world:

I’ve never resonated with the Save the Cat books, despite so many others turning to them and advocating for them. I tried. But the formulas and the genres just don’t connect for me. Like many storytelling systems I find it sends me down rabbit holes and into confusing terminology and exercises that kill the energy of a story for me. I’d much rather find the innate structure of the story I want to tell and do my best to fulfill that potential.

I've thought for a long time that the worship of the Hero's Quest and Blake Snyder's books is what's mostly put me off blockbuster movies these days. Thanks for making your stand known on the false promises some people have latched onto.