20 Essential Silent Films You Can Watch for Free on YouTube

Enjoy this curated collection of silent masterpieces from around the world available for you to study, like, right now

The digital streaming age had a chilling effect on world cinema, more often than not burying access to films that once occupied our video store shelves or, because of the dominance of physical media, could be easily purchased on VHS, DVD, or Blu-ray. Many titles aren’t even available today via digital rental services like Apple and Amazon, forcing cinephiles to either search libraries, eBay, and flea market bins for treasures or, if they’re lucky, locate what they’re looking for on platforms such as YouTube where financially strapped distributors and fans with a hankering for public domain titles, upload films. I love to wander YouTube because of this, just as I used to wander Blockbuster. This 5AM StoryTalk resource is the result of that effort, a chronological list of twenty essential silent films available to watch for free.

For filmmakers in particular, these twenty films from around the world are MasterClasses in how to visually tell stories rather than weigh them down with unnecessary exposition. In fact, consider this article a follow-up to one I posted a few days ago entitled “The Sound Of Silence: Denis Villeneuve’s Problem With Dialogue”.

Please note that this list is limited to American, European, and Soviet titles, which make up the bulk of my knowledge of the Silent Era of cinema. There is much more to discover and learn from what originated elsewhere around the globe, and I’d certainly appreciate your suggestions in this regard. Additionally, female directors are not represented on this list despite their presence behind the camera at this time; history has been as unkind to the early story of the female filmmaker as it has been to female artists throughout the centuries, and I’m only just beginning to correct their erasure from this period in my own cinematic education.

Enjoy!

A TRIP TO THE MOON (1902)

Dir. Georges Méliès — France

There were attempts at true “films” before A Trip to the Moon, but none remotely grasped the potential of cinema like Georges Méliès, whom I would call the George Lucas or James Cameron of silent film. This short started everything.

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE (1920)

Dir. John S. Robertson — USA

This chilling adaptation of the Robert Louis Stevenson novel stars John Barrymore as the titular characters and, along with a 1931 adaptation that starred Fredric March, captured my imagination as a teenager. Years later, I returned to them for inspiration as I worked on my graphic novel The Strange Case of Mr. Hyde, itself a sequel to Stevenson’s novel.

THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (1920)

Dir. Robert Wiene — Germany

Robert Wiene’s horror is a masterpiece of German Expressionism and, for my money, the first truly great monster film ever produced. More than a century later, its Somnambulist still terrifies as he creeps through painted shadows that slice like knives. Everything about it deserves your attention.

THE KID (1921)

Dir. Charlie Chaplin — USA

The Kid was Charlie Chaplin’s first feature, both as an actor and a director. It’s considered one of the greatest films of the Silent Era, too, largely because of Chaplin’s innovative juxtaposition of heartbreaking drama and comedy. It proved you could move people while making them laugh.

NOSFERATU: A SYMPHONY OF HORROR (1922)

Dir. F.W. Murnau — Germany

This is the first great vampire film, so iconic today that people are more familiar with the startling image of Max Schreck as Count Orlock— a blatant Dracula knock-off — than the film itself. Much of this has to do with how director F.W. Murnau employs German Expressionism to create his terrifying images.

A smart cinephile would watch this and then Werner Herzog’s remake. An even smarter cinephile would make it a triple feature, culminating in Shadow of the Vampire (2000), a feature about the making of Nosferatu with Willem Dafoe dazzling as Schreck.

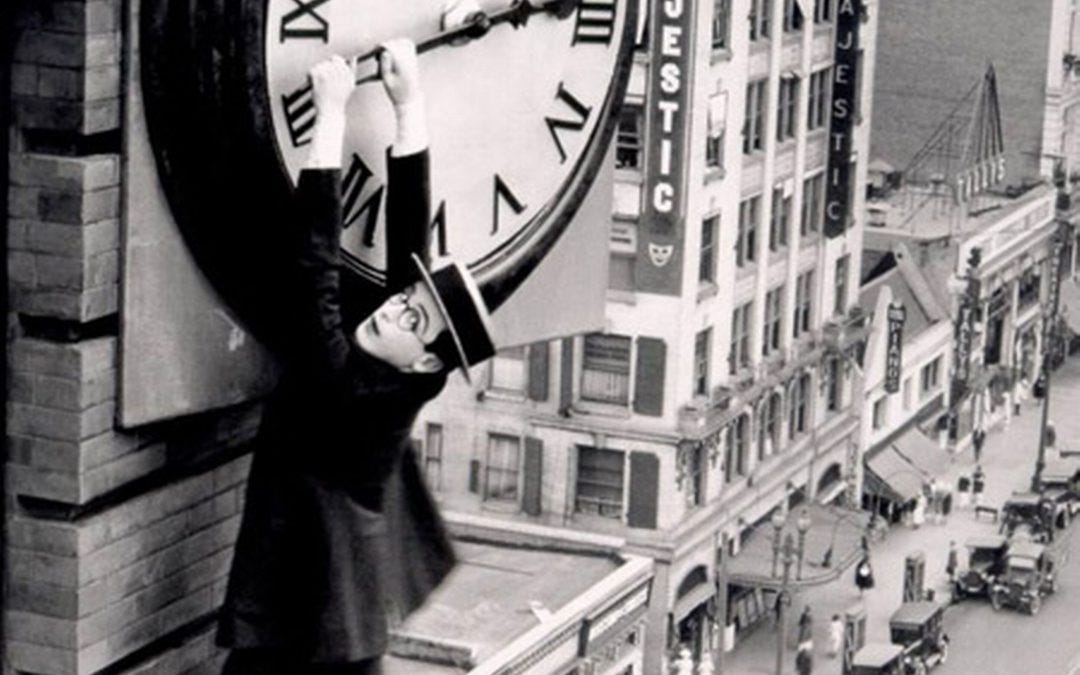

SAFETY LAST! (1923)

Dir. Fred C. Newmyer & Sam Taylor — USA

Safety Last! is another silent film more famous today for how its infiltrated the rest of popular culture than the film itself. It stars the genius comic actor Harold Lloyd, who ends up hanging off the side of a building — specifically a clock that won’t cooperate with his attempts to escape falling to his death.

THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME (1923)

Dir. Wallace Worsley — USA

This was actor Lon Chaney’s first role as one of the monsters that would become synonymous Universal Studios in the thirties and forties. While the Hunchback never officially joined that pantheon, he’s always been included thanks to Chaney’s spectacular performance (and make-up) in this film.

BATTLESHIP POTEMKIN (1925)

Dir. Sergei Eisenstein — Soviet Union

Watching Battleship Potemkin a dozen times is the equivalent of two years of film school, as far as I’m concerned. The director basically invented juxtaposition in cinema, contributing more to the art form than just about any other director in history.

THE LOST WORLD (1925)

Dir. Harry O. Hoyt — USA

Eight years before the stop-motion in King Kong changed cinema forever, this little film about dinosaurs and other giant, fantastical creatures thrilled audiences. There’s never been a truly great adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, but this comes close.

THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925)

Dir. Rupert Julian — USA

While the 1925 Phantom of the Opera film does not officially mark the beginning of the “Universal Monsters” series, it really does. Lon Chaney plays the titular scarred monster who terrorizes the Paris Opera House long before Andrew Lloyd Weber did. The performance is iconic, to say the least.

STRIKE (1925)

Dir. Sergei Eisenstein — Soviet Union

Strike was released in the same year as Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, a cinematic achievement roughly the equivalent to Steven Spielberg making Schindler’s List (1993) and Jurassic Park (1994) at the same time. Like Potemkin, it features a climactic sequence worthy of much study, this one of the violent suppression of a strike cross-cut with the slaughter of cattle.

FAUST (1926)

Dir. F.W. Murnau — Germany

F.W. Murnau’s second film on this list. In it, the demon Mephisto makes a bet with an archangel that he can corrupt a righteous man’s soul and destroy all that is divine in him. If he succeeds, the Devil wins the Earth. So, small stakes. It’s easily one of the visually astonish films of the Silent Era, which is probably why it went on to influence imagery in Disney’s Fantasia (1940).

WINGS (1927)

Dir. William A. Wellman — USA

Wings is one of the greatest American films of the Silent Era, an epic love story set against the backdrop of World War I. Your jaw will constantly drop at what director William A. Wellman put on screen, from aerial dogfights to a now-iconic tracking shot I consider the greatest in cinema history. In fact, I recently discussed it here.

METROPOLIS (1927)

Dir. Fritz Lang — Germany

Metropolis cannot be described; it must be experienced. I mean, not really. It’s not the Matrix or something. But it is the greatest science-fiction experience in cinema history until 2001: A Space Odyssey came along in 1968. Fritz Lang, one of the essential directors of the first half-century of cinema, created a dystopian nightmare about capitalism and hot robots that has never stopped influencing filmmakers or being relevant.

SUNRISE: A SONG OF TWO HUMANS (1923)

Dir. F.W. Murnau — USA

F.W. Murnau’s third film on this list, Sunrise, is no less visually innovative than the other two even though it concerns itself with events far more mundane than vampires and demons. A farmer unhappy with his tedious, unexciting life allows a woman from the city to seduce him and convince him to drown his wife so they can be together. God, those city gals! Needless to say, drama ensues.

THE LODGER: A STORY OF THE LONDON FOG (1927)

Dir. Alfred Hitchcock — United Kingdom

The Lodger is Alfred Hitchcock’s first thriller and, as such, it’s fair to say this is where it all started for the Master of Suspense. This is where the verb “Hitchcockian” was born. If you’re someone who values being scared at the movies or aspires to make films that scare the hell out of people, I encourage you to dive into this one to see how it’s done when you strip dialogue out of the story.

STEAMBOAT BILL, JR. (1928)

Dir. Charles Reiner & Buster Keaton — USA

Buster Keaton was a comedy genius who, like Charlie Chaplin, gained control over the films he made. Tragically, that control was short-lived and ended one film after Steamboat Bill, Jr. Like Safety Last!, this is a fun one to watch with the kids who will no doubt find Keaton’s most famous film stunt — the facade of a house falling around him while he stands in an open window to avoid being crushed — as enjoyable as you will.

PANDORA’S BOX (1929)

Dir. G.W. Pabst — Germany

Pandora’s Box was wildly controversial at the time of its release, from the promiscuity of its lead character to a lesbian sub-plot. Consequently, it was hacked at and butchered to make it “acceptable” to audiences, the kind of censorship conservatives have always enjoyed imposing on anything that violates their delicate sensibilities. Over the decades, the original cut began to make the rounds and wow critics and filmmakers alike and, today, has been restored.

UN CHIEN ANDALOU (1929)

Dir. Luis Buñuel — France

This surrealist classic is a short experience, but an unforgettable one. It challenges and defies and rewrites cinematic language like few films of its time. It’s also still deeply disturbing today. Maybe that’s why it shows up on Akira Kurosowa’s list of his 100 favorite films, which I recently wrote about; the other being The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA (1929)

Dir. Dziga Vertov — Soviet Union

Man with a Movie Camera was a transformative experience for me when I first saw it. It’s not so much a film as a visual symphony, a mind-breaking cinematic orchestration the likes of which I have only rarely witnessed. The only instruments employed are the director (Vertov), his editor, and the multifaceted Soviet Union they present in the film.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

I have also seen Un Chien Andalou (thanks to The Pixies)

I have seen Safety Last (referenced in BTTF and Hugo), Potemkin (required film school viewing), Trip to the Moon, and Metropolis (thanks to Janelle Monae). Have you seen Vampyr?