There Are More Ways to Tell a Screen Story Than Hollywood Wants You to Believe

World cinema provides a broad education in how to challenge, subvert, and innovate the narrative norms of the Hollywood studio system

Earlier this year, screenwriter C. Robert Cargill (DOCTOR STRANGE, THE BLACK PHONE, and more) took to Twitter to share some advice about screenwriting that I think is worth considering wherever you are on your screenwriting journey. I’ll let you read his words for yourself.

So, what you need to know is: this advice is entirely correct…from a Hollywood perspective. I practice it myself when writing on American projects.

It’s also entirely incorrect…from the perspectives of, say, many independent U.S. filmmakers and, more robustly, filmmaking traditions around the globe.

Because cinema is, of course, far more than how the Hollywood studio system says we’re allowed to tell stories with moving images.

Let’s now consider the work of two Japanese filmmakers to illustrate what another country’s film tradition would make of Cargill’s advice. Not to disprove Cargill in any way — I know and admire his work and he knows the point I’m making himself — but to help aspiring and emerging screenwriters begin to flex their narrative imaginations beyond the “rules” most commonly espoused by “Hollywood”.

Please note I could do this with UK, French, Soviet/Russian, and Italian cinema all the same. I’ve chosen these specific Japanese filmmakers simply because their styles exist in dramatic contrast to the Hollywood mode of filmic storytelling described by Cargill.

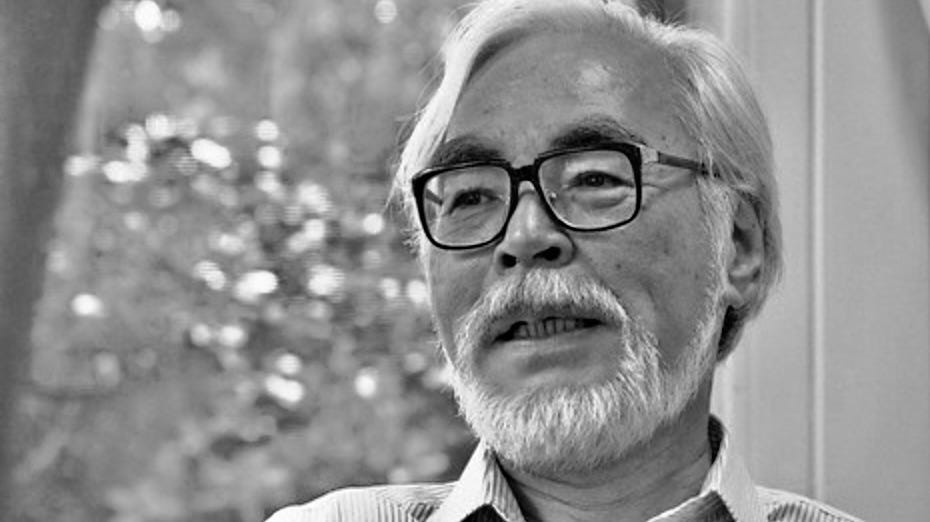

Hayao Miyazaki

The following is a snippet of a conversation that film critic Robert Ebert had with Hayao Miyazaki — a filmmaker many consider the greatest animation screenwriter and director in history (an opinion I happen to share). This is the person who gave the world PRINCESS MONONOKE (1997), SPIRITED AWAY (2001), and HOWL’S MOVING CASTLE (2004).

I told Miyazaki I love the “gratuitous motion” in his films; instead of every movement being dictated by the story, sometimes people will just sit for a moment, or they will sigh, or look in a running stream, or do something extra, not to advance the story but only to give the sense of time and place and who they are.

“We have a word for that in Japanese,” [Miyazaki] said. “It’s called ma. Emptiness. It’s there intentionally.”

Is that like the “pillow words” that separate phrases in Japanese poetry?

“I don’t think it’s like the pillow word.” He clapped his hands three or four times. “The time in between my clapping is ma. If you just have non-stop action with no breathing space at all, it’s just busyness, But if you take a moment, then the tension building in the film can grow into a wider dimension. If you just have constant tension at 80 degrees all the time, you just get numb.”

At this point, Ebert suggests this is why Miyazaki’s films are so much more absorbing and involving than the “frantic and cheerful action” in much of American animation. What Miyazaki says next is what I would describe as a polite rebuke of Hollywood’s relentlessly aggressive narrative style.

“The people who make the movies are scared of silence, so they want to paper and plaster it over,” he said. “They’re worried that the audience will get bored. They might go up and get some popcorn.”

Yasujirō Ozu

The Japanese verse concept of “pillow words” Ebert alluded to has a cinematic equivalent called “pillow shots”, which were largely innovated by the legendary director Yasujirō Ozu. Ozu would interpose an enigmatic series of shots between scenes in his deliberately paced films, providing his audiences the ma Miyazaki just described and much more.

Here is film journalist Leigh Singer writing about Ozu’s pillow shots for BFI:

Though these cutaways maintain the gentle, measured rhythm of Ozu’s work, their seemingly benign nature belies their effect. While his early career incorporated comedies and gangster films, it’s the later shomin-geki or ‘modern family drama’ (many with similar, seasonal titles and dealing with close parent/child relationships) that epitomize Ozu’s influence on cinema. These stories are understated, and the pillow shots are a wonderfully subtle way to evoke the passionate emotions roiling below the surface.

And here you can find a superb super-cut of Ozu’s pillow shots:

The takeaway: cinema is not Hollywood’s studio system, and Cargill’s description of the absolutist utility of every word/moment of a screenplay/film can and does comfortably exist alongside how Miyazaki uses ma (space) in his films and Ozu employed contemplative visual interpositions.

So-called “rules” — and Hollywood has many — do have value, and they should certainly be studied, understood, and even taken advantage of, but God didn’t write them on celluloid and give them to Sergei Eisenstein atop Mt. Sinai. They’re subjective, as culturally distinct as they are muddied by our globalized society, and predisposed to evolve and even regress.

This is why I strongly encourage you, if you aspire to work as a screenwriter in the Hollywood studio system, to expand your understanding of cinematic narrative language by studying international film in all its forms. Especially from countries with traditions that initially confuse you.

In doing so, you might find new ways to challenge, subvert, and even innovate Hollywood’s “rules” yourself.

If you’re wondering where to start, here are twenty masterpieces of world cinema, including two of Ozu’s, that will make you rethink the best way to tell your next screen story:

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

I totally agree, Cole! I’d dare to say - as I am hard consumer of oriental cinema/tv/written and drawn literature - that the hyper logical occidental narrative has (almost) killed the magic of storytelling.

Also - sadly this is only on MAX but if you look at the Ghibli films tab there you can find a repeating loop of all those nature and quiet moments from all their movies strung together. It's kind of amazing to just put in the background while writing or reading.