Where The Love Light Gleams (Or: Christmas as Ritualized Trauma)

'I'll Be Home for Christmas' and similar ballads share a common origin that explains why they're so good at helping us exorcise personal and cultural grief at the holidays

“I'm dreaming tonight of a place I love”

On Christmas Day, 1968, my grandparents and their daughter woke and opened presents together just as they always had with one exception – my father was thousands of miles away from their rural family house north of Detroit, serving his first tour in Vietnam.

To make it through the morning, my grandfather had already downed a tumbler of cheap whiskey, or so I can only assume. This was typical for him anyway, but this holiday was especially hard because he’d spent many Christmases away from his own family during World War II. He understood what war was. Every day after he returned home from the construction sites where he worked as a carpenter, he insisted on supper being finished in time for he and my grandmother to watch the evening news together. That’s because new footage of U.S. soldiers waving at the camera, at their loved ones back home, was always shown. My grandfather hoped to catch a glimpse of his son, my father, in one of them.

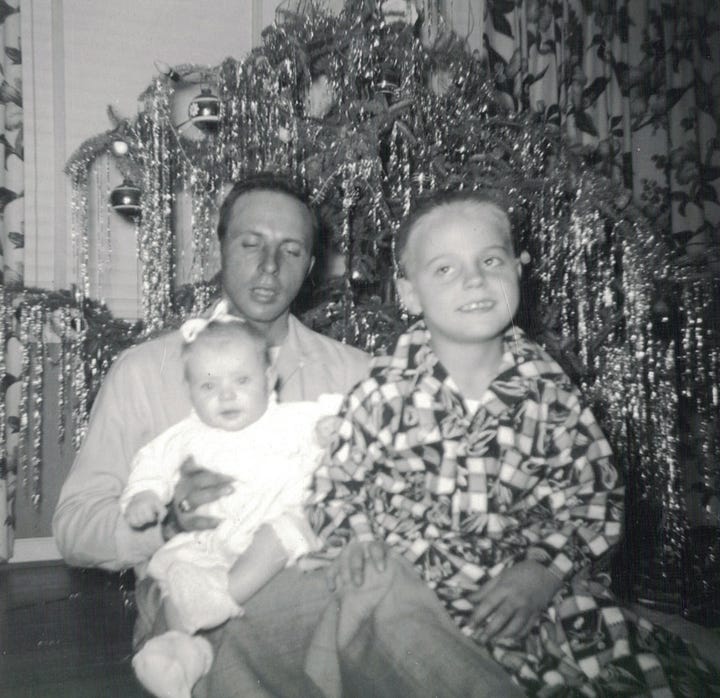

On Christmas morning in ’68, however, my grandparents - and my aunt - would only see my father beneath the Christmas tree where a framed photograph of him, in his service uniform, stood amidst other decorations. Years later, during the Gulf War in 1990, my grandparents would again have to put my father’s photo under the tree like I just described.

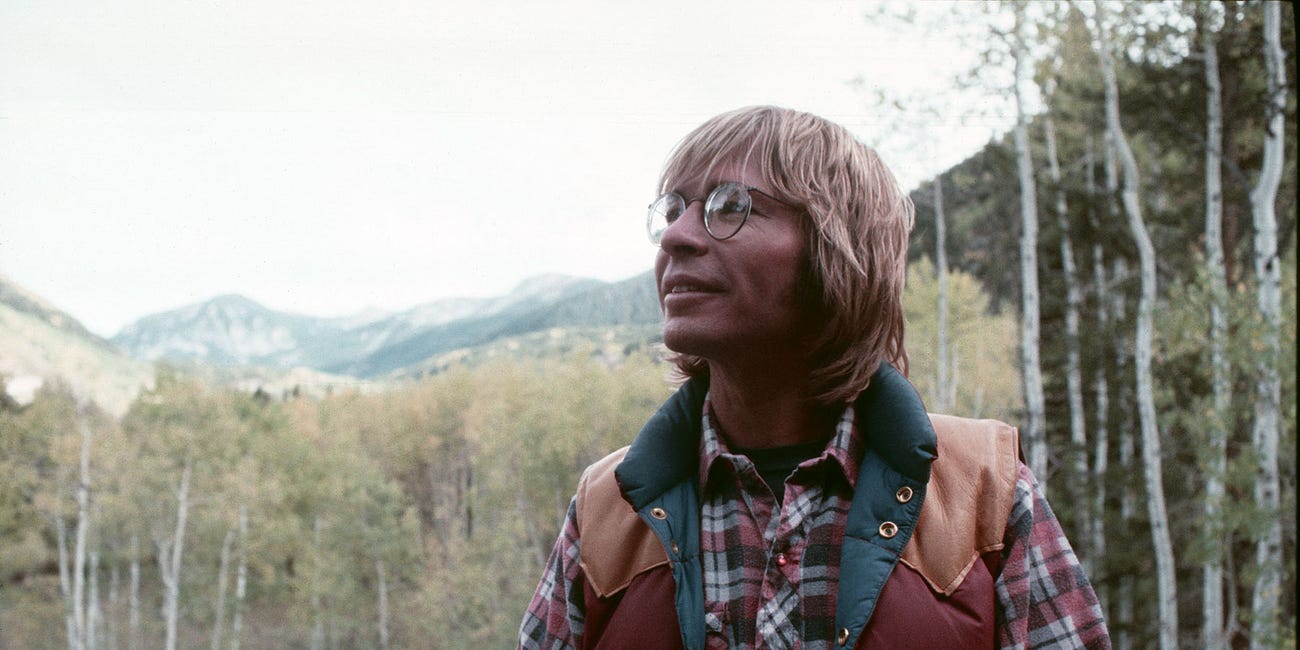

For most of my forty-eight years, I only knew about this Christmas that took place eight years before I was born because of stories others had told me and a single photograph of that morning. But newly restored 8mm family films recently brought it alive for me in an entirely new way.

There were my grandparents, younger than I ever knew them in real life, trying to be jolly despite the mortal danger their son was in. There was my aunt, an only child on this particular year. There was my father’s picture displayed beneath the Christmas tree. As for the pine, chopped down in the woods on the acreage out back, it looked just as most had when I spent Christmases there years later. The living room was almost exactly as it still is in my memories of the house, too.

I wept as I watched this 8mm footage because everything captured in it is gone. My grandparents are dead. My father is dead, along with my mother who arrived from Australia a few years later to marry him. This year, my aunt, the last living member of the preceding generation of my core family, died. I am haunted by their memories, of a family, of a place, of a time that will never be again.

All I have left are the stories they gave me.

But maybe that’s okay. Stories are what we’re really made of, after all. More than cells, more than stardust, more than whatever magic you otherwise believe in. They tell us who we are because they tell us who we were. These stories, compiled from our memories and others’, are different for each of us. Some come to us through people other than our family, sometimes through friendship and other forms of love, sometimes through geography. But their meaning, the word we give to them to describe how they make us feel whenever we think of them, is always the same…home.

“I’ll be home for Christmas”

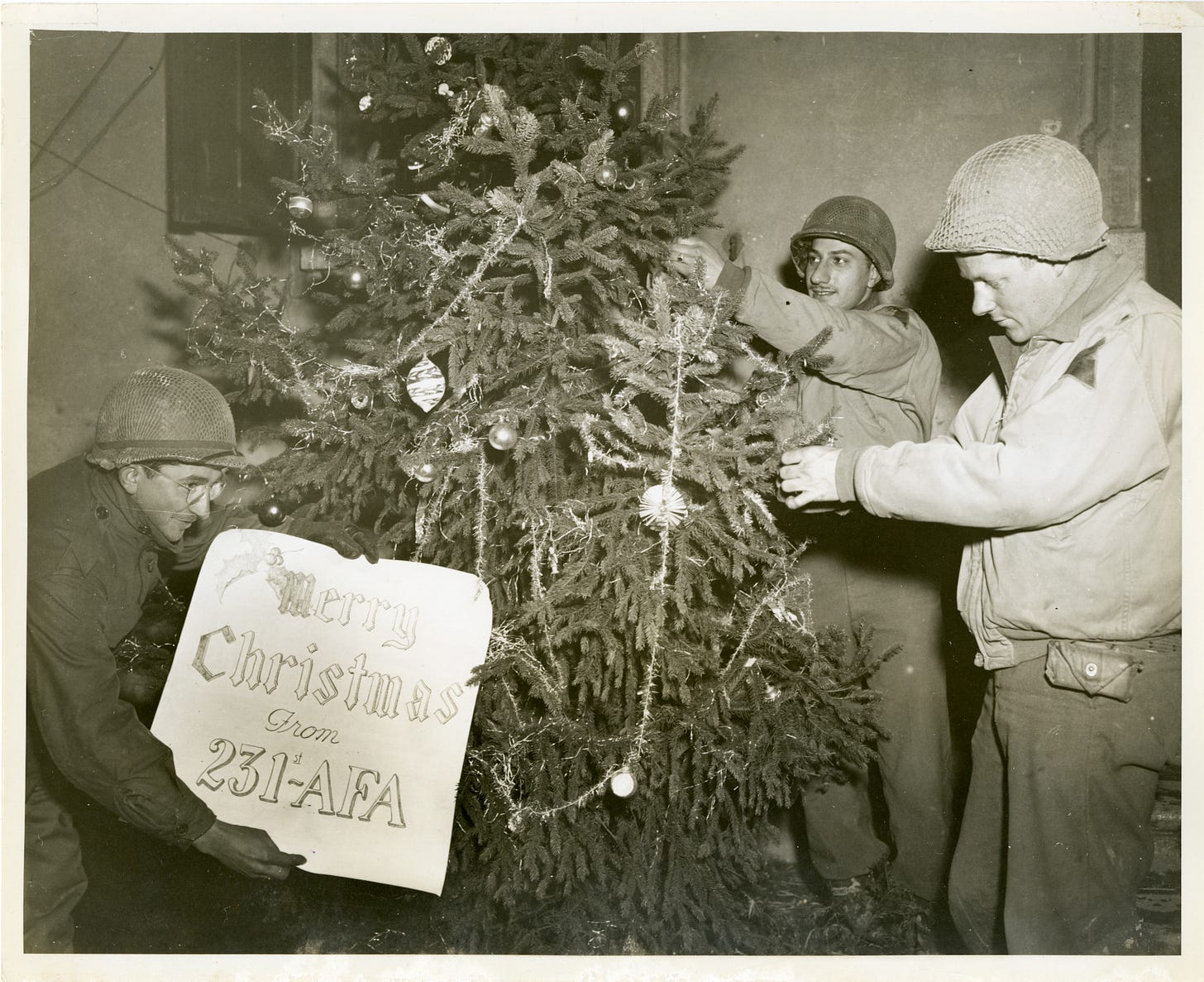

As the final months of 1943 arrived, the United States of America had been at war with the Axis Powers for almost two years. My grandfather was stationed in the South Pacific, where he served as a top turret gunner on bombing runs. Millions of other Americans were fighting in similarly violent fronts around the globe, thousands of miles away from their families - in many cases, loved ones they hadn’t seen since they joined the war effort after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. There was no end to the war in sight either.

You can imagine then how the song “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” was received by those both abroad and those they left behind when it first hit airwaves that October.

Lyricist Kim Gannon and composer Walter Kent wrote this song for Bing Crosby, who was the first to record it in ’43. It followed his smash hit “White Christmas”, which was released the year before after premiering in the film Holiday Inn. Both songs share a lot in common. Rather than embrace any of the typical frothiness of the season, they present instead sentimental ballads about the season, fairly unusual in Christmas music history at the time. “I’ll Be Home for Christmas”, in particular, was a deceptively melancholy reminder of how such a reunion was impossible for the near future and, perhaps, ever. It’s why the song’s original subtitle was “(If Only in My Dreams)”.

Personally, I prefer Perry Como’s version of the song, which was recorded and released in 1946 after World War II was over. Crosby and Como had very similar voices, to such a degree that Como was dismissed early in his career as a Crosby knock-off. But in this case, I think Como’s carries with it the weight of the United State’s four years at war. All I hear is a dirge.

“Please have snow and mistletoe”

Before World War II, Christmas songs had taken much poppier forms that people could joyfully sing along with around the tree, at office parties, and school pageants such as “Winter Wonderland” and “Santa Claus Is Comin’ to Town” (both released in 1934), "What Will Santa Claus Say (When He Finds Everybody Swingin'?)", or “I’ve Got My Love to Keep Me Warm” (1948). But as the war dragged on and the number of U.S. dead skyrocketed, ballads became the preference to reflect the emotional states of most families.

In addition to “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” and “White Christmas”, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” and “The Christmas Song” were all also released during the period between the U.S. declaring war and V-J Day, and all either directly referenced or evoked a desperate yearning for being home and a restoration of something that’s been lost.

“I'm dreaming of a white Christmas

Just like the ones I used to know”

“Someday soon, we all will be together

If the fates allow”

“Everybody knows a turkey and some mistletoe

Help to make the season bright”

At the war’s conclusion in September of 1945, with order apparently returned to the universe, so too was good old-fashioned fun reintroduced to Christmas. “Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!” was recorded just after Japan surrendered and became a huge Christmas hit that year. “Christmas Island” followed in 1946, “Here Comes Santa Claus” in 1947, and “Sleigh Ride” and “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” in 1948.

Interestingly, Perry Como added “(There's No Place Like) Home for the Holidays” to this list in 1954, a year after the Korean War ended, which in many ways is a direct rebuttal of the grimness of his take on “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” — and another example of a war-scarred culture rebounding back to upbeat, feel-good music at the holidays.

“If only in my dreams…”

The lyrics to “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” are worth considering in the context of this conversation:

I'm dreaming tonight of a place I love

Even more than I usually do

And although I know it's a long road back

I promise youI'll be home for Christmas

You can count on me

Please have snow and mistletoe

And presents under the treeChristmas Eve will find me

Where the love light gleams

I'll be home for Christmas

If only in my dreamsI'll be home for Christmas (I'll be home for Christmas)

You can count on me (you can count on me)

Please have snow (have snow) and mistletoe (yeah)

And presents under the tree (under the tree)Christmas Eve will find me

Where the love light gleams

I'll be home for Christmas

If only in my dreams

If only in my dreamsIn my dreams, my dreams

My dreams

As I already mentioned, the song’s title no longer includes the subtitle “(If Only in My Dreams)”, but even a glance at these lyrics makes clear how essential those words are to the song’s original meaning. Without them, we tend to popularly remember the song as a feel-good number about making it home for the holidays. I’ve seen it in more films than I can count, used this way. “Hey ho, I wonder if Joe Schmo will make it home to his wife and kids this year!” There’s always a happy ending in these films.

But “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” is not a happy song.

That’s because it’s not actually about getting home by Christmas, if that’s not evident by now. The lyrics “I'll be home for Christmas/You can count on me/Please have snow and mistletoe/And presents under the tree” are a fantasy, a wish upon a star, a desperate prayer.

“If only in my dreams/If only in my dreams…”

What “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” and similar Christmas ballads are really about is trauma.

“And although I know it's a long road back”

Popular music has a way of transporting us back to earlier moments in our lives, both good and bad. This is a well-documented phenomenon and one that tends to be very subjective outside of culture-shaking events. But the Christmas ballad - specifically those that originated during World War II - hold a very different, unique place in music history because they don’t fade from our collective consciousness as generations pass. They return every holiday season like clockwork, whether we want them to not, summoning the ghosts of the past. We have no choice, in turn, but to participate in this cultural exhumation of everything we’ve lost as individuals and as a culture.

I’ve come to view this as a form of ritualized trauma.

Ask yourself if you experience the same level of emotional dread listening to “Jingle Bells” or “Frosty the Snowman”. Of course not. Religious hymns might evoke similar in you - I, an atheist, struggle with “Silent Night” at times - but these require a spiritual affinity and even then they speak of heavenly matters rather than earthly ones.

Christmas ballads, on the other hand, are secular songs that very often vibrate at the spiritual level. They speak of what we’ve lost here, not in some other plane of existence that may or may not even be there. They’re about losses that hurt more at the holidays, losses we all understand, losses we all share even if their dimensions aren’t the same.

“I’ll Be Home for Christmas”, in particular, is no longer a song about loved ones separated by war for years on end. History has moved on, and so has the song. Instead, it now speaks to a more universal feeling — missing someone, some place, some thing that we can never get back. This is because we all know we can never go home, and with every year we live, home - however we define it - grows ever further away.

But why would we participate in this yearly ritual of missing, melancholy, and mourning?

“Christmas Eve will find me”

Trauma is the steep toll we must pay for living. Unlike death, it demands payment year by year, though, thankfully, for most of us it we don’t really start feeling the existential pinch until around middle age.

By middle age, the losses are too numerous to pretend away, mask, or drown in drink. We try to ameliorate the damage by turning them into safe, touching stories we tell others, especially our children, but there are too many stories to tell, as it turns out. Some are too ugly anyway. So, we pack them up and put them on a shelf somewhere inside our hearts, or however you want to describe that place inside you. We do it to keep going, as a way to keep ourselves from becoming distracted from the myriad joys that still exist elsewhere in this beautiful world.

This is a good way to get by, but trauma tends to need attention from time to time or it will get the best of you. Like a shoebox of old photographs 8mm films, we periodically need to blow the dust and mustiness away, say hello to the ghosts we’ve been trying to ignore, and remind them - and ourselves - that they were loved, that we were loved in turn, that things were different once upon a time before, well, life.

These Christmas ballads help us do that, I think. They allow us - all of us who have any relationship to the holiday - to yearly participate in a ritual of mourning and, ultimately, renewal.

Our participation in this transitional ritual is unconscious, but also collective. Because while all of our lives and traumas are unique, our cultural relationship to these songs is not. They signify the same thing to each of us, I mean, so we can all participate in the same ritual every holiday season regardless of our personal story DNA.

For example, a film can use Perry Como’s “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” and most of us in the audience will have a Pavlovian response — or rather, release. The idea of home, whatever that means to us - that place we each know we’ll never get back to - triggers a profound sense of melancholy. For no reason we can understand, tears might even rim our eyes. Then, come the memories…

I want to demonstrate what I’m describing here, though I will have to beg your patience so I can make my point. Earlier, I mentioned that I had recently had 8mm family films restored and converted to digital files. I described one, in particular, of a Christmas morning in 1968 when my father was away from home, in Vietnam, and he and his family had to spend it apart. Here’s a video of that film I’d like you to watch:

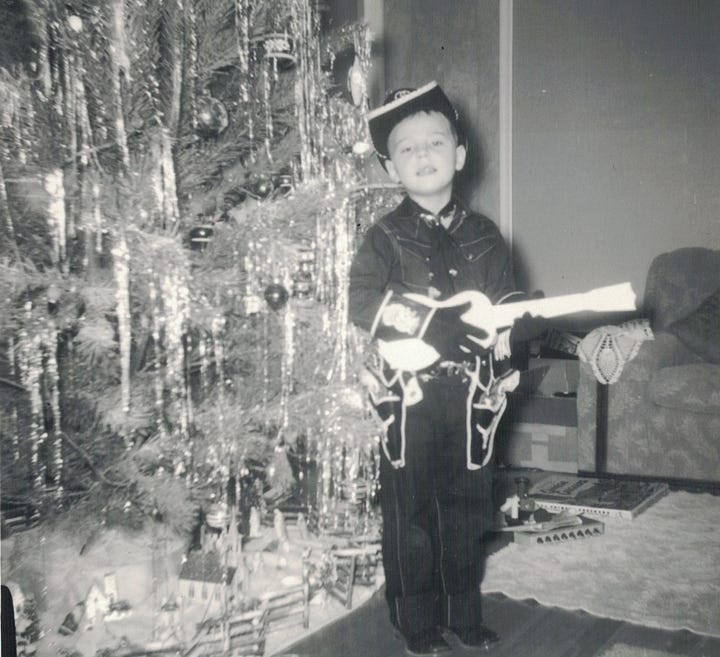

I’m sure you noticed, but there’s no sound. The images convey a typical white working-class family in the U.S. in 1968, in a modest house, enjoying a version of Christmas that very possibly makes you feel a slight pang of nostalgia as long as you have a past in a country Christianity left its stamp on. You’ll have noticed my father’s photo under the tree, too. But I expect your relationship to this film is one of disconnected familiarity, nothing more.

Okay, now I want you to rewatch it. I’ve added a little something to it.

Was the experience any different with Como’s “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” playing over it? I’m willing to bet it was. Not because the film itself is suddenly more familiar, but the song provokes familiar feelings in you, feelings about your own yearning for a place you can only return to in your dreams — and you applied that to my grandparents’ home film. Strangers are immediately more familiar to you, as a result. You probably even found yourself missing your own family members long gone while watching mine.

“I’ll Be Home for Christmas” not only helps me reach back in time to a part of my story I’d lost, but it makes my story your story in a way. Conversely, it makes your story my story. This is what happened in World War II, when the song was experienced by all U.S. servicemen and their families, a kind of shared memory of trauma, and every decade since as it’s replayed on our radios and covered again and again by new generations of musical artists. Another description for this is intergenerational trauma.

In other words, “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” is one of the greatest Christmas songs ever composed not because it’s actually about Christmas. But because it’s about loss, both our own specific losses and a collective memory of a more nebulous but no less traumatic cultural loss. Every Christmas, it reminds all of us about our own personal stories of where we come from and how far we are from home, about what we’ll never get back except in our dreams, about a hurt that we will never recover from, that we will carry forever, that we will not stop missing.

This is my fourth Christmas without a living parent and it’s been almost two decades since I sat at my grandparents’ table on Christmas Day, surrounded by all the people who will, despite distance, differences, and death, always feel like home to me — a home I can never return to.

But the stories I tell my children extend beyond this metaphorical home. I grew up on the border of Detroit, which was my physical home for more than half of my life. The city’s highways are like veins and arteries in my imagination, carrying me back there and beyond, to the country where I was born.

In 2016, I left the United States to start over abroad because I have a moral disagreement with it, but I always hoped it would one day feel like home again. That one day, it would stumble headfirst into its own promise. But this Christmas, I now understand that will never be, or at least will likely never be in my lifetime. The future is the future, bleak as it appears to be, for a very long time…and the past is a place that I’ll never back it back to except in my dreams.

“Where the love light gleams”

What I try to take comfort from is the knowledge that darkness tends to pass.

White Christmas (1954) is popularly recognized today as a Christmas musical, but it’s actually a musical about World War II and, in particular, the fraternity of veterans that returned after the war’s conclusion. I watched it most Christmases growing up with either my mother or grandmother. Released nine years after the war ended, it stars Bing Crosby (amongst others) and, in glorious Technicolor, tells the story of two American G.I.s-turned-crooners who attempt to save their beloved former general’s hotel over an especially warm Christmas in Vermont.

The film begins on the European battlefront with a rendition of “White Christmas” that does indeed sound like mournful dirge, no backing music except for a music box tinkling nostalgically away like a children’s xylophone. The battle-weary G.I.s in the audience tear up listening to it, thousands of miles from their loved ones just as my grandfather was in the Pacific at the same time in history.

Nine years later, when the when the main thrust of the film White Christmas takes place, the song is again performed to close the film out. But this time, it’s not a mournful solo. It’s celebratory, performed by a whole room full of veterans who survived the worst war the world has ever seen and have nothing but tomorrow and all its possibilities ahead of them.

My point is, yes, the past is a place we will only make it back to in our dreams, and there’s no time of the year that quite reminds us of that as powerfully as Christmas does. But there’s also no time of the year more charged with hope for tomorrow and all its possibilities.

If Christmas ballads are prayers to the dead and everything we’ve lost, they can also be prayers to everything we may yet become. Maybe that’s part of why we need them so much this time of year — yes, they’re a form of ritualized trauma, but they’re also there to remind us that home doesn’t just live behind us. Home changes, sometimes so radically we no longer recognize it. And it goes on. Somehow, improbably, it goes on…

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

This is beautiful and heartbreaking all at once, Cole. I am better for having read it and thank you for writing such a personal, though universal, piece. May it find its way to all who need to hear it, feel it, or remember; how important it is to never forget our generational memories, histories, and how our families found their way through some of the hardest, most heart-heavy times of their lives. That the music of the time was salve for the soul during such upheaval and loss, as much as it was a way to document how the hearts of humanity felt such longing and sorrow, yet hope, during these traumatic times. May we, in our country's current state , live and survive in such a way that future generations will look back on the lives we've led and see that the same love and resolve came from us to survive and get through our traumas. Let's hope the music created today can and will reflect how we made it through. Though, I haven't heard any with the same significance as those past classics you've highlighted — yet. With hope, as these next few years progress, I pray there are musicians who will give it all word and song; to create ballads that not only reflect the turmoil and brokenness, but give voice to how we got through it.

Had not intended to say so much, but your piece really moved me. I suspect I will be swirling your words around for a while. Much appreciation for your contemplation and thoughtfulness to the subject. A Happy Holidays hoped for you, and us all.

Many blessings,

~Wendy 💜

Thanks for sharing this and the analysis of how music connects us together. I also lost both of my parents in the past 3 years and Christmas just isn't the same anymore.