We're All Trying to Escape a Dystopian Thriller Now

That time I pitched 'Squid Game', Luigi Mangione, and why Hollywood and the media will do anything to protect the super-rich

Eleven years ago, six years before the South Korean TV series Squid Game became a global hit, I pitched a remarkably similar film around Hollywood. This isn’t to suggest anyone stole my work. Both my idea and Squid Game are not all that conceptually original in the dystopian space they occupy. But the reaction to my project is going to illustrate how ill-suited the United States film/TV industry is to contend with the biggest problems of our day and hopefully offer some perspective on why America’s media is falling over itself to convince you that UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson’s alleged assassin is one of the greatest villains in American history — up there with John Wilkes Booth, Lee Harvey Oswald, and James Early Ray.

Here's the elevator pitch for Escape the Room (remember, this was five years before Escape Room was released by Sony, so it was very much ahead-of-the-curve with regard to the escape room craze):

Five 20-somethings wake up in a strange building made up of real-world “Escape the Room” puzzles. None of them know each other, or how they got there, but they’re about to discover that they’ve become contestants in a sick and ultimately deadly game in which the super-rich gamble on the successes and failures of their victims.

And here’s a block of the opening of the pitch itself, which I present to you in its original bullet point form. For context, I don’t memorize my pitches. I type them out, one idea per bullet point, then blow them up to 22 font with key words and phrases in caps. In this way, I can more or less visually reference the printed document in my lap without ever noticeably reading from it.

One percent of the world’s population controls more than 40% of global wealth.

In other words, everyone else lives at the mercy of this 1%.

Most of us are pawns in their constant attempt to horde even more of humankind’s wealth and resources.

Figurative pawns, of course.

But what if we were more than that?

What if the 1% began to play us like we were nothing but game pieces?

The METZGER MAZE, a series of REAL-WORLD ESCAPE THE ROOM PUZZLES, is the answer to that—

Involuntary CONTESTANTS participate in a game of life and death as the super-rich gamble on the outcome.

These Contestants, ripped from everyday life, are lost 20-somethings.

A new generation cast adrift by climate change anxiety, an unstable economy, and the collapse of the American Dream.

They played their own proverbial games of life, trying to come out on top, and life kicked their asses.

Tonally, think David Fincher’s early work here.

The intensity and moral ambiguity of SEVEN, as well as a cinematic puzzle every bit as complex as the actual game – like Fincher’s THE GAME.

But mostly, I just want to try to capture the angst and confused, violent rage of our time.

ESCAPE THE ROOM is, if anything, cinematized rage against the machine.

When you’re young and feel there’s no hope left, what else can you do except strike back?

I’m sure you can see the strong conceptual similarities to Squid Game at this point. Again, not to draw any kind of damning comparisons, but to ultimately illustrate how Hollywood is almost entirely incapable of developing and making something like the South Korean series. Because when it does, the system somehow goes on the offensive, like white blood cells, to make sure the status quo remains “healthy” and unchanged (see: The Hunt’s fate).

The system — which is unchecked capitalism, which is a world where billionaires rather than politicians make decisions about our lives, which is a world where billionaires even get to become idolized super-heroes on our screens — cannot, must not be seriously challenged.

Okay, now I’m going to tell you how my Escape the Room pitch ends. The following is lifted directly from the document I used, though I’ve modified a few parts of it for clarity. I imagine this will be useful to aspiring screenwriters, by the way; not everyone breaks a pitch down like this, but I find it the most effective method for me.

Here, Em and Cordell [our final two surviving heroes] start by trying to solve the puzzle…

But when they find a bone saw, Cordell decides to change the rules – by sawing their way out of the puzzle, right through a wall.

Before they crawl through this hole, Cordell kisses Em.

They’re going to get out of here, he promises.

Together.

On the other side of the wall now, they find themselves in a utility corridor that leads them to a—

MAINTENANCE ROOM.

Em and Cordell try to use the phone, but it’s dead.

There’s an iron door, but it’s locked.

Light streams through a keyhole, suggesting it’s the way out.

And that’s when they realize that despite their perceived victory—

This maintenance room is yet another puzzle room.

The key to the door must be found.

Cordell discovers a hand-wand metal detector and uses it to search for a key, only to incidentally pass it over Em.

She buzzes.

He tries her again, and the metal detector reveals that it’s her belly giving off a signal.

Em takes the metal detector and tries the same on Cordell.

His belly gives off the same signal.

What the hell?

And then a small black & white TV blinks on.

On the screen: Metzger’s face, smiling.

We’ve come to Em and Cordell’s final test: which one of them will kill the other to get the key to finally escape?

Because only one of them can leave this room alive, he’s made sure of that.

Em refuses.

She won’t play his sick game.

And then Cordell turns, tears rimming his eyes.

In his outstretched arm, the gun Val used on Asher.

“I-I’m sorry, Em,” he stammers.

She couldn’t be more surprised.

He pulls the trigger.

BANG!

Em startles, but isn’t hit.

“I’m going to chalk that up to the stress you’re under,” Metzger says, laughing.

“Blanks, remember?” he says. [This makes sense given scenes that preceded this one.]

Em’s eyes fill with fury.

She snatches up a large wrench and swings it into Cordell’s head.

Cordell drops.

Blood running from his head wound, he tries to rise.

Em hits him again.

He drops, leg twitching.

And then it stops twitching.

In the Gambling Suite, Sen. Warren Pickett, who had bet against Em, is stunned by this turn of events.

A veteran himself, he recognizes a true warrior deserving of his respect.

He now approves of what Metzger has created, and asks if he can join them for the next Metzger Maze.

“But of course, Senator,” the Hostess tells him.

Back to Em.

She again arms herself with the bone saw and uses it to hack into Cordell’s belly.

Here, she retrieves the LARGE KEY there.

This is the film’s only real demonstration of true, traditional horror.

She winds up splattered with blood, a gory baptism of sorts.

When she rises, Metzger says he imagines she has many questions.

But all Em wants to know is “Why?”

Metzger explains that, though Em might not believe this, he wanted to help her.

He wanted to help all of them.

The Metzger Maze isn’t a game.

It’s a test and, like all tests, it reveals.

“In this case, what one is not…and what one is.

“Life used to be like this, not so long ago really,” he says.

But Man meddled with the ancient rules.

He thought he knew better than Nature.

How wrong He was.

“But then,” Metzger says to Em, “you know that now, don’t you?

“You know the truth.

“The blinders, so to say, have been removed.

“Tell me—and, please, be specific—what do you see?”

Em, covered in blood, roars, “I’m going to fucking kill you!!!”

Metzger slowly smiles, pleased.

“Ah, that’s my girl,” he says.

“You’ve passed with flying colors then.”

As Em screams obscenities at Metzger, he tells her she’s welcome.

The TV blinks off then.

Blood-covered and triumphant, transformed, Em opens the steel door to escape…

…and finds herself in yet another puzzle room.

Two other confused Contestants she’s never met look back at her.

She’s not free.

Because THERE’S NO WINNING in this billionaires’ game.

The game, like the reality of life on the outside, does not end until you die.

Cut to black—

THE END.

Pretty fucking bleak, right?

It’s obviously an allegory for how the super-rich profit off of everyone else’s suffering and death by turning the so-called “lower classes” against each other. At the end of the day, class solidarity is only possibly amongst billionaires; everyone else is too busy scrabbling to cobble together a life worth living to worry about anyone else.

Early in the pitches, I sat down with a studio executive I had worked with multiple times at this point. They found my scripts fun and hopeful, summer blockbusters with a conscience. But hearing about Escape the Room left their mouth literally hanging agape. When they collected themselves, they skipped any kind of polite bullshittery such as, “Oh, that was so well told” – the typical stuff execs say when they’re not interested – and jumped right to, “Why would you ever want to write this, Cole? It’s so nihilistic.”

There was genuine concern in their voice when they asked this. They were horrified by the story I had proposed to them, but maybe even more horrified by the fact that I thought it was worth telling.

As for me, I was confused by their reaction. It seemed so obvious that this nihilism was the only authentic ending to my characters’ journeys and the story. But more than that, I thought it was honest and would be received as much by its primary, far younger audience. I said some version of, “I think what I want to do is to tell kids they’re not crazy. I want to tell them that the despair they’re feeling is real, it’s warranted, and that the only way to really ‘escape the room’ is to finally do something about it.”

Of course, there are many ways to define what that means — “do something about it.” My solution has always been non-violent protests, work stoppages, and other societal disruptions such as congesting infrastructure with human bodies. But I’m also very quick to point out that billionaires are a crime against humanity and the French used to know how to fix this problem. There is a limit to the physical and emotional suffering, the bloodshed, the death that the rich and powerful can inflict before a population snaps, I mean.

Long story short: the studio executive I’m discussing passed hard on Escape the Room. I went on to sell it to Blumhouse, where the project ultimately died in development like so many projects do. That’s okay because screenwriter Hwang Dong-hyuk created a much better version of the story with Squid Game. A key difference with what he came up with is his contestants choose to participate in the violent, lethal game for the fantastically unlikely chance of becoming rich — which really is capitalism at the working-class level in a nutshell.

When Squid Game did become a huge hit in 2021, I sent an email to my Escape the Room producer and we had a quick chuckle about it. I pointed out how American audiences were eating up the incredibly “bleak” series, and I was reminded yet again that what audiences crave, even what they need, is not the same thing as what corporations — including ones predicated on art — are typically willing to provide them. Bear in mind, Big Pharma doesn’t even develop cures; it develops treatments for disease that keep you coming back for more. While there are some exceptions, is Hollywood’s history much different when it comes to class warfare?

Yes, art should confront and challenge audiences, even make them profoundly uncomfortable, but if it encourages them to reject their culture in any way, then you’ll often run into a wall at the studio/streamer level. Squid Game gets away with this because it’s a South Korean series. South Korea has a different relationship with art, class, capitalism, and such – which is how we also got Parasite, a horrifying class allegory that won the Best Picture Oscar in 2019.

The U.S., by contrast, would prefer to give the world Wall Street and “Succession”. Both of these works of art are brilliant, of course, but they center the idolatry of extreme wealth that’s the beating heart of Western culture rather than the “lowly” individuals who are daily violently exploited by adherents to this sick religion.

Personally, I have always been attracted to and enjoyed art that smacked of something anti-civilization. Not civilization itself, but rather the idea of it that the super-rich constructed for us in the West since monarchies ceased to be the chief movers of power in the world. Any system that can successfully murder hundreds of millions of people and cause the suffering of billions can’t be so great as to deserve heroes, I think.

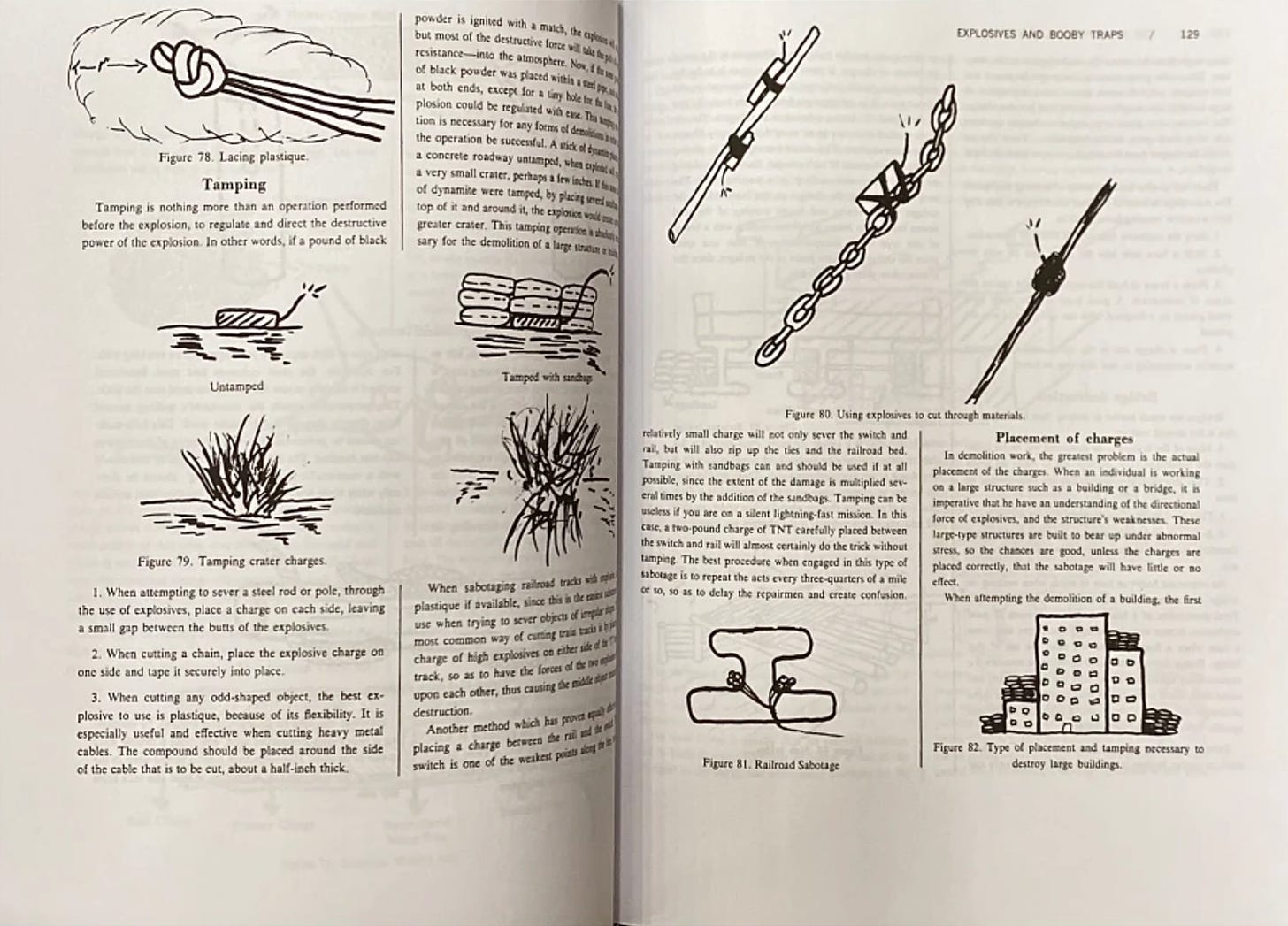

Maybe this is why as a teenager I loved Edward Abbey’s novel The Monkey Wrench Gang (1975), which concerned environmental protesters targeting industrial efforts in the American Southwest; in fact, this is where I discovered that all you need to do to stop earthmoving machines is to dump sugar in their gas tanks. This was around the same time I was introduced to William Powell’s The Anarchist Cookbook (1971), which told anyone who picked it up how to build bombs, mess with telecommunication systems, even make LSD as a way to effect societal change; it’s available to download for free today from the Internet Archive if you’ve never read it.

More recently, I was deeply moved by the film How to Blow Up a Pipeline (2022) from director Daniel Goldhaber; it’s fiction, but it plays out like a documentary concerning the titular act. And while researching for a thriller TV series I’ve been developing, I stumbled upon the once top-secret Simple Sabotage Field Manual (1944), a mind-blowing set of instructions for committing “purposeful stupidity” written by the CIA’s precursor, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

In both of these cases, as with Abbey and Powell’s books, the precariousness of civilization is revealed. We like to believe this world we’ve built is somehow made of adamantine steel, but that’s a fallacy. Ancient Rome fell in the blink of an eye compared to how long it had endured. No, our way of life dangles from a string.

If you don’t believe me, then ask yourself why so many billionaires have built impregnable bunkers for themselves.12

What do they think is going to happen to necessitate their retreat from the rest of the world? They know the game they are playing, how strip-mining our world and bank accounts for extreme profits, how refusing to share it as billions starve and choke and drown as ocean levels rise, can and most likely will result in collapse.

There is no escape to Mars, no matter what kind of beachfront of red sand Elon Musk is trying to sell you. Space is not colonizable in any future we can currently imagine. Earth is our last stand, it’s the only home we will likely ever know too, and that’s why these robber barons are ready to spend the planet’s last days in lonely underground palaces.

This is what Squid Game was reacting to, this is what Parasite was reacting to, this is what Escape the Room was trying to react to.

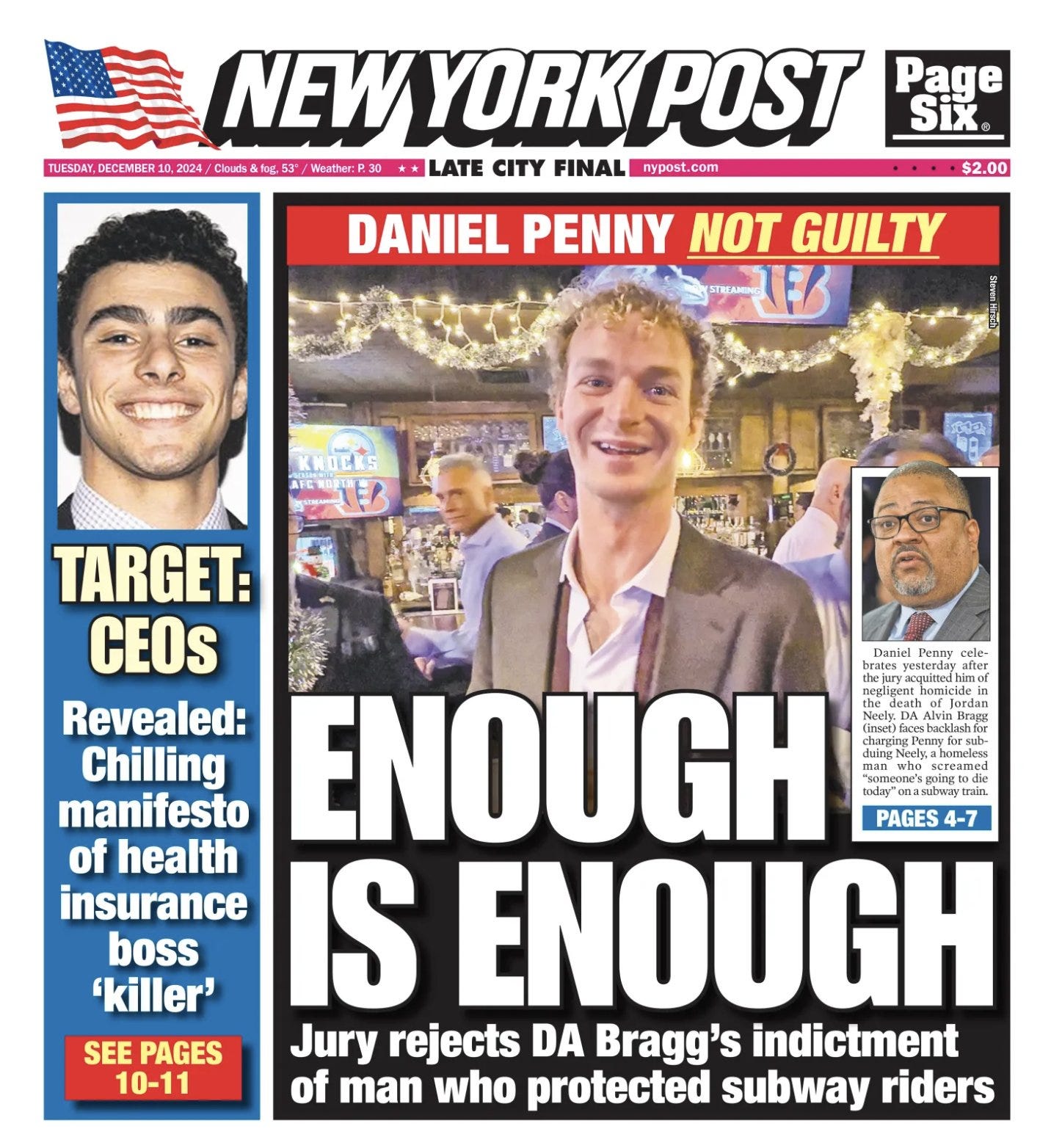

In the days since 26-year-old Luigi Mangione allegedly assassinated the CEO of a health insurance company with the highest claims denial rate in the business and who had only recently overseen bribing Democratic politicians in California into shutting down a health care for all bill, the U.S. media has depicted Mangione as a monster. As for the CEO who had directly and indirectly contributed to the suffering, deaths, and financial ruins of millions, he’s discussed as a saint (titans of industry almost always are portrayed this way, of course, regardless of their crimes).

At the same time, a 26-year-old white man who murdered a mentally ill unhoused Black man on the New York Subway was found innocent by a jury and had his face splashed across newspaper covers across the country like he was the second coming of Kyle Rittenhouse.

Such a strange contrast, isn’t it? Kill a billionaire and the media wants you hunted down and crucified, but if you kill a Black man failed by his society, with nothing in his pockets, you’re a hero.

But this is all the legacy media conglomerates are good for these days, even the alleged Left-leaning ones that are servants to the elite all the same. Why would they bite the hands of the billionaires who feed them? (Same goes for Hollywood, by the way.)

The simple truth is: power in the West must protect itself at all costs, even if it means using the media to try to convince people they should be sadder about the person in the mansion than the guy living on the streets. Political parties are irrelevant as the major ones largely serve the same masters. Billionaires’ ability to billionaire — squeezing us for every last penny they can, even as we gasp and beg for mercy — is all that matters.

Activists trying to draw attention to the climate crisis are a threat to that status quote, protesters decrying the murder of George Floyd by cops are a threat to that status quo, a young man who appears to have engraved "deny," "depose", and "defend” on bullets before firing them into a healthcare CEO is a threat to that status quo.

But just as dangerous as them are all the people at home who might empathize with their rage against the super-rich, who might celebrate such people as folk heroes as Americans have long regarded vigilantes and other anti-authority types, who might take to the streets themselves and act next.

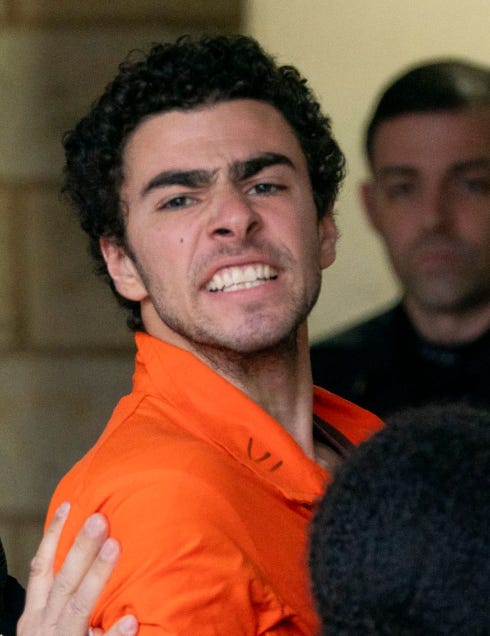

This is what Mangione was referring to as he arrived at court, I think, when he shouted, “It’s completely out of touch and an insult to the intelligence of the American people and their lived experience!”3 His rage is the rage of tens of millions of Americans who have had their lives ruined, by people like Brian Thompson — regardless of how legal what these healthcare CEOs do is. These people — these victims — know the game is rigged against them (just like the characters in my Escape the Room pitch discover, by the way).

Speaking of which, here’s Mangione’s lawyer Tom Dickey being interviewed by Kaitlan Collins at CNN about the unexpected outpouring of support his client has received from people across the U.S.4:

Collins: …people are reaching out to you and offering to help pay for his legal bills?

Dickey: That's correct.

Collins: Would you accept those offers?

Dickey: Nah, to be honest with you, I probably wouldn’t. … It doesn’t sit right with me.

Collins: Why do you think they’re offering?

Dickey: You’re talking about, the Supreme Court says all these rich billionaires can give all kind of money to candidates and that’s “free speech”. So, maybe these people were exercising their right to free speech — and they’re saying that’s how they’re supporting my client.

Obviously, the murder of anyone is a horrible crime, and I and all decent people condemn it. But an assassination like this also feels…I don’t know…inevitable, doesn’t it? Nothing about it seems shocking, I mean. Instead, my reaction was and remains more like, “Why doesn’t this happen all the time?”

Because if you create a generation or two of people who feel they have nothing left to lose, then remove any serious obstructions to them arming themselves, it does seem like this should actually be happening all the time — at least when we look back at human history. That it isn’t is the well-financed, socially engineered miracle by which billionaires continue to prosper.

I can’t think of many things I want less than to live in a world where violently victimized people believe their only recourse is to terrorize and murder others, but I understand their despair, I empathize, and I will do what I can to use my art to challenge the powerful on their behalf – and my own.

That’s not easy, of course, as the gatekeepers so often unwittingly serve the oppressors. I should’ve known my anti-establishment, anti-everything take on Escape the Room would disgust Hollywood rather than disrupt it. Such ideas, I now understand and accept, are better suited to novels and fine art and more independent forms of cinema and music and comic books — or, here at Substack, of course, where the only limit to your ability to confront and discomfort and blow up the status quo through your words is…you.

But if I were a billionaire sunbathing on the deck of my super-yacht right about now, I don’t know if I’d be all that concerned about me or any other artist. I’d be worried about Luigi Mangione instead, who feels a lot more like the start of something more dangerous, more potentially socially disruptive than just some freak act of violence we’ll all forget about in a few months. Could Brian Thompson really be the only person to pay a price for all the blood that’s been spilled in the name of record corporate profits? There’s an entire planet populated by victims that really makes me doubt that.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2022/sep/04/super-rich-prepper-bunkers-apocalypse-survival-richest-rushkoff

https://www.vice.com/en/article/billionaires-are-building-luxury-bunkers-to-escape-doomsday/

https://www.msnbc.com/chris-jansing-reports/watch/luigi-mangione-shouts-as-he-arrives-to-courthouse-226673221510

https://edition.cnn.com/2024/12/10/us/video/tom-dickey-luigi-mangione-lawyer-src-intv-digvid

This is a brilliant article! I'm posting it on LinkedIn (I'm sure it has been done already ).

I'd like to offer a positive response to this. By about fifteen years ago I was lamenting American inaction on this kind of stuff. At that time, the Brazilian poor were so aggressive against their ruling class that the plutocrats had to basically live in bunkers. They had to armor all their vehicles, and in reading about it I found out what a tremendous undertaking it is to armor a Mercedes Benz so your child doesn't get kidnapped on the way to school. Today, Brazil is doing far, far better, and creating wonderful video all the time. I'm sure you saw "City of God", but maybe not the Netflix shows "Nobody's Looking" and "Omniscient". They're worth checking out, and their existence makes it seem that America is currently in the darkness before the dawn.

Also, most of the stuff in the anarchist's cookbook is bullshit. I had it as a teenager and bounced things off, like, my chemistry teacher. IIRC, he even got the recipe for acid wrong. You could probably write a more dangerous book. I know I could.

I did print out your sabotage manual. I like that kind of veracity in my stories. Didja ever notice that "Hardcore Henry" teaches you how to self-set a broken wrist?