Q&A: Writer-Director Keith Powell on Being a Diversified Artist

The ‘30 Rock’ alum’s Zen-like approach has provided him a broad education in storytelling — from stage to screen — and helped him weather the typically uncertain life of an artist

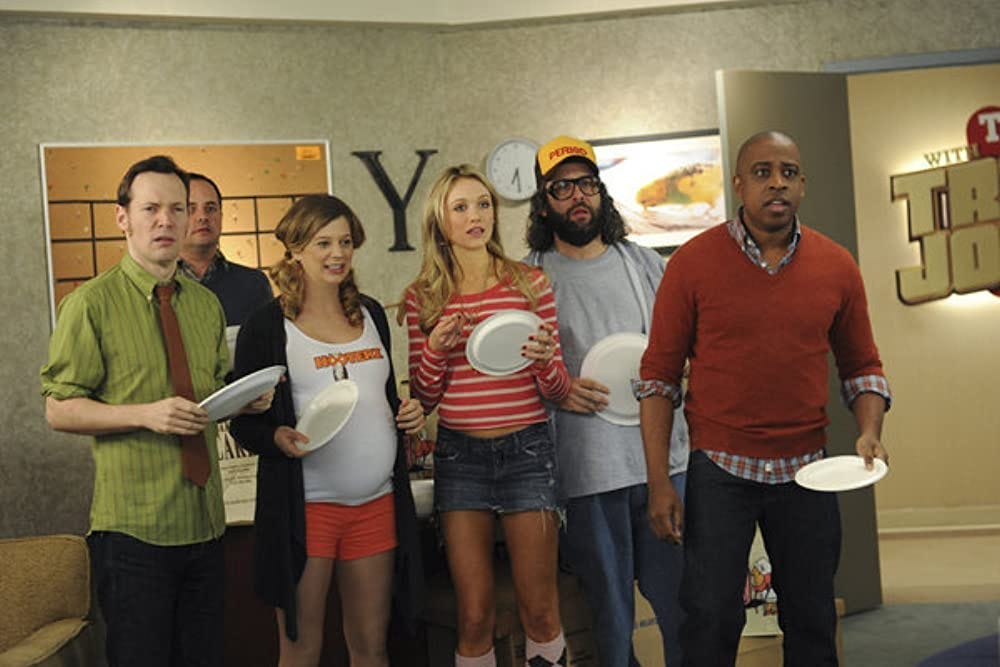

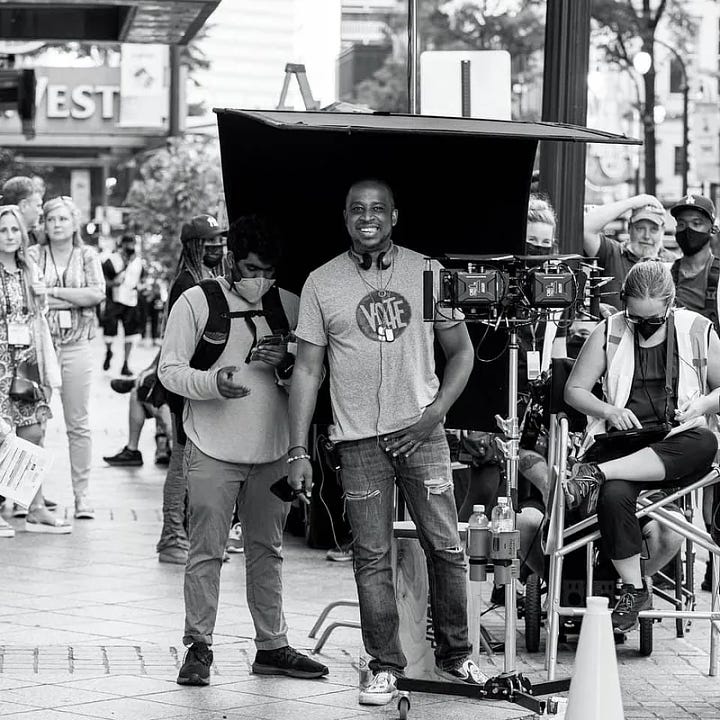

Chances are, you’ve seen Keith Powell’s work as an actor. He was a regular on “30 ROCK” for seven seasons — you’ll remember him as Toofer — and he’s appeared on so many other series since that I don’t have the time to type them all out. But for this latest installment in my artist interview series, I wanted to chat with him about his career in theater and behind the camera instead — with a specific focus on his screenwriting and, more recently, his success as a director on TV series such as “Dickinson”, “Interview with the Vampire”, and “Young Rock”.

The resulting conversation often felt more philosophical than practical, except for the fact that Keith’s Zen-like approach to his art has repeatedly produced radical new and successful directions in his professional life. I know he suffers from anxiety like most artists do, but I can’t help thinking he’s navigating it better than most of us.

There’s much to learn from the tension that exists between Keith’s surrender to whatever amounts to fate in the arts and his commitment to creating his own art as a way to forge new opportunities for himself. The result has been an incredibly diversified career, one that has enriched his storytelling and helped him weather down times such as COVID.

COLE HADDON: It’s great to catch up like this, Keith. While we only really know each other through the Writer’s Guild of America and social media — in fact, I think we “met” on a Facebook group during the 2020/21 agency action — I feel like I’ve gotten a very good sense of who you are and, especially, your passion for the arts and storytelling through your posts and our interactions. Over the past two years, in particular, I’ve been incredibly excited by the directing work you’ve been landing, what feels like one impressive gig after another. You’re one of the lucky few who seem to have not only survived COVID, but somehow came out better on the other side.

KEITH POWELL: By the grace of God, COVID never really slowed me down because I’ve thankfully had a diversified career — so when one thing wasn’t happening, I could take advantage of another. At the beginning of the shutdown, I was hired by HBO Films to write a movie about the Attica Prison riot. It was during a time when I couldn’t get arrested as a director, so I was happy for the work. When that project wound down — I got my final check — I was hired as an actor to be on a “film at your own home” sitcom for NBC with my wife [called “Connecting”]. That was a fun few months. Then, a friend asked me to go and direct an episode of the show she was running.

CH: Was that “Dickinson”?

KP: It was! God Bless Alena Smith, an old friend who has always known me as varied artist. It’s a more involved story on how that happened, but the timing was just right, and I went to do that. Directing on “Dickinson” opened the floodgates for my career as a director, so I’ve just be riding those waves for the past few years. Really, I try to be open to all avenues and possibilities and kind of let the wind blow me in the direction it sees fit — did I just mix metaphors? Ah well, it all applies.

CH: Was there a period where you tried to control your career’s trajectory more, or have you always been so Zen about the work?

KP: The Zen has definitely taken time to mature. My grandmother — [who was] one of my parents and my daughter’s namesake — used to always tell me “What’s yours will know your face.” It drove me crazy at the beginning of my career because I kept saying, “Then what’s mine?!”

“Life unfolds in ways you don’t expect, and it’s the unfolding that is where one can find joy and peace.”

But as the years progressed and as those words rang in the back of my head constantly, I realized that it’s a matter of slowing down and letting the process happen. Life unfolds in ways you don’t expect, and it’s the unfolding that is where one can find joy and peace. I don’t always adhere to this philosophy — I’m only human — but I definitely try.

CH: So, what are you working on at the moment? Tell me what your days are like lately, because you seem to be juggling a lot.

KP: This is actually a down-time for me work-wise. Last year, I directed episodes of shows back-to-back-to-back and I was getting burnt out creatively. I took the month of December off, and that kind of bled into January. Now, I’m juggling a few things — my next directing gig is [later this month], I’m interviewing for two big directing jobs for after that, and I’m helping to develop a pilot I would direct. My days are pretty busy, but they’re filled with more time to relax, and think — which is key to being an artist. Just having time to think.

CH: I have to say, I’m jealous of your freedom to do that right now — to think. It’s interesting, because during a recent conversation with visual artist Joe Forte, I pointed out how people outside of Hollywood don’t understand how so much of a filmmaker’s life is waiting around for somebody else to give them permission to create, to be artists, to do their jobs. But with that wait comes a hellish, sometimes debilitating amount of anxiety you instead spend on trying to come up with some other project that will get people excited, that will keep your career moving forward.

KP: I actually don’t think that way.

“Listen, I can’t predict when or control if someone will hire me — and I hate that and it gives me all the stress — but I can control my artistry.”

CH: Really? Tell me more.

KP: I know the stress and lack of work is hellish and debilitating, but I genuinely don’t think I am waiting around for someone to say “yes” to me. Maybe that’s my strength and my flaw. When I was a teenager, my high school acting teacher told me that an artist’s life is difficult, and I need to be aware of these periods of inactivity and rejection. He told me the only way to get beyond that is to make work for yourself. Wake up every morning and be an artist. Do something artistic. Sometimes that’s making the perfect omelette. Sometimes that’s tackling a screenplay. Listen, I can’t predict when or control if someone will hire me — and I hate that and it gives me all the stress — but I can control my artistry. I don’t want anyone to ever take that away from me. I refuse. So, I do my art, and then do the work and fight of getting it seen.

CH: That’s some amazing advice from your high school acting teacher. Let’s use that as an excuse to take a detour back in time a bit. I want to give readers some of your secret origin, if you will. What was your relationship to the arts as a child? Did you always know you wanted to lead a creative life when you grew up?

“Seeing a story I wrote about minorities being marginalized performed by my white peers lit a fire in me somehow — the power of storytelling to show complex ideas.”

KP: I think I realized that I wanted to be an artist somewhere around the eighth grade. It’s weird, because my parents — my grandmother who was a legal secretary and my mother who is a payroll accountant — were never really the “artist” types per se. But they were great observers of human nature and loved the art of storytelling and greatly valued Black history. I was the only Black kid in an all-white private school. And I was asked to write a paper about the Encampment at Valley Forge — an American Revolution event — and instead I wrote a play about the Black soldiers who stayed there. My teacher encouraged the whole class to perform it. Seeing a story I wrote about minorities being marginalized performed by my white peers lit a fire in me somehow — the power of storytelling to show complex ideas. I was hooked.

CH: As for how you started out in the arts professionally, it wasn’t as a TV director, or a screenwriter, or even an actor, which is how, I think, most people would know you through your work on “30 Rock” and “About a Boy”. Your first passion was the stage, right?

KP: Right

CH: Walk me through how you got from working in theater on the East Coast to, let’s say, “30 Rock”.

KP: I ran a theater company called Contemporary Stage at an insanely young age. Lynn Redgrave performed in the first play I produced. It was wild. I was twenty-three, and had no idea what I was doing.

Over the years, I started directing for the company, and there was one play I directed that was about to go on a national tour. I needed to fire the set designer, but I didn’t know how to do it. So, I wrote him a letter and delivered it to his agent. That agent was more interested in my career, so he asked if he could send me out on auditions. The first and only one he sent me out on was “30 ROCK”.

CH: Sorry, but fuck me, are you serious?

KP: Fuck yeah! That was the beginning of my transition to TV and film, something I was always interested in in school — I began as a TV/Film major in college, but transferred to theater directing — but it always seemed out of reach.

CH: Screenwriter Meg LeFauve — maybe you know her? — she recently reminded me the artist’s journey is a long game. In your case, you made it to Hollywood all the same, but likely with a lot more valuable experience and insights to inform your work.

KP: I don’t know her, but she sounds wise. Again, it’s about trying to embrace the journey of it all and not the result.

CH: What did directing for the stage teach you that has made you a better director for screen today?

KP: Story is king. Character motivation is paramount. I can have those conversations and get to the heart of what story we’re all trying to tell. It’s the purest form of directing — the lights, camera, sound, costumes — all are just in service to telling a good story.

“It’s character first. I bring that into all my writing.”

CH: I imagine that also impacted your approach to screenwriting?

KP: Each medium emphasizes, I think, a different artist. And playing to that emphasis is important to keep in mind. In TV, I believe the writer is king. In film, the director. And in theater, I truly believe the actor because they are up on that stage and in control of the script whether you want them to be or not. In that regard, I think theater tells stories that really allow the actor to dig deep and express complicated ideas. So, it’s character first. I bring that into all my writing. I believe that’s what HBO Films saw in me and why they bought my [Attica Prison riot] pitch in the room. Expressing complicated story through characters.

CH: These days, I think of you as a rare jack of all trades when it comes to the performing arts. Stage, screen, writer, director — but also an actor and one who has been very successful at it, not just bit parts. On one hand, being an annoyingly talented multi-hyphenate means endless creative possibilities and employment opportunities, more so than the average, say, artist living in New York City or Hollywood, but, on the other hand, it presents more opportunities to be unfocused. To not devote yourself to anything with the appropriate commitment. How have you managed how you’ve pursued employment — because artists need to pay their bills, at the end of the day — how have you managed where you apply your passions?

“I mostly go where the artistic winds take me, and I try to devote myself to that direction wholly and fully at the time.”

KP: As I said before, I mostly go where the artistic winds take me, and I try to devote myself to that direction wholly and fully at the time. It has created some issues for sure. Mostly, perception. I fight really, really hard to get people to not put me in a box. “Oh, he’s just an actor.” “Can he really write?” “You only do comedy, right?” The comedy versus drama thing in particular has been extra-hard to overcome. I believe all the best comedies have drama and all the best dramas have comedy anyways, so I am agnostic to comedy and drama.

CH: Absolutely.

KP: I just keep telling people who I am — I’m an artist that loves stories. Sometimes I tell them as a director, sometimes I create them as a writer, and sometimes I’m the vessel through which the story is told as an actor, but it’s all in service to telling good stories. Lately, I’ve been focused on directing — and it’s been wholly fulfilling to me. I just need to keep reminding people that I’m not all one thing and that’s a good thing. That’s a good thing! You want diversified artists. They are able to understand all the plates that are spinning. So that’s the struggle.

CH: I’d like to hear more about your recent run of directing work, which feels like you were doing the jobs of several different people — at least from the outside. I can’t imagine that doesn’t come with its own considerable amount of stress. Obviously, everything is easier when you’re gainfully employed and, even better, doing something you’re passionate about, but working at the level you are right now must take its toll and come with entirely different anxieties.

KP: Television directing is its own beast. As I said, TV is primarily a writer’s medium, so a director is there to service the writer. My job, I think, is to tell a story from my own personal POV in that writer’s style. So yes, there are major challenges in navigating that and, in many ways, it’s stressful being constantly in service to other artistic tastes.

But I see it this way: imagine you are going to someone else’s house and cooking them an entire Thanksgiving meal to their specifications from all the ingredients in their pantry. But then, you decide to throw a little whiskey into the gravy. Or sage. Or whatever is your own personal twist. Sound stressful? It is. Especially doing it at a high volume. But it’s so gratifying when folks taste your whiskey-sage gravy and love it.

CH: Now I’m just hungry. Not cool.

KP: Hop across the pond, and I’ll fix you a meal. I love to cook.

CH: Maybe next time I’m in LA!

CH (cont’d): As artists, creation comes in many forms. Quite often, it’s in service to someone or something else, as you just described. But do you have any space that’s just yours, for you to create on your own terms whether others chose to engage with it or not? Are there canvases of Keith Powell masterworks hiding in your closets or a play or novel you peck away at when you have the time?

“Every job I approach I go back to a simple idea: what is the story, and how do I find myself in it? It’s just that simple.”

KP: About a decade ago I pledged, no matter where I was in my career, to create one short film a year. So, my pure voice can remain center to my artistic life. I’ve made about ten. A few are up on Vimeo. Not all are winners, so some will never see the light of day. But I’m proud of the ones I’ve made public because it shows my evolution as an artist. Now that I have kids, it’s a little harder to justify the expense of making one every year, so my output has slowed down a bit. But I’m eager to jump into another when the timing and money is right.

CH: Final question. One of the reasons I started this artist interview series was to talk with fellow artists, especially the diversified ones, as you put it, about the intersection of mediums, the conversation that can and does take place between different art forms — so I couldn’t agree with you more. I’m curious…you’re in your forties now and exceptionally accomplished in several branches of the arts. It sounds like very little of that journey was planned or even imagined, the result of “artistic winds” as you say. Can you talk about how all those ingredients — the whiskey, the sage, the etcetera — play out every time you go to work (whatever the job is that day)?

KP: Every job I approach I go back to a simple idea: what is the story, and how do I find myself in it? It’s just that simple. Because finding what impassions you, what drives you, what makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand up, is the work of an artist. The great set designer and teacher Ming Cho Lee, God rest his soul, taught a guest class at NYU while I was there. He said — and I’ll never forget it — “Rally for stories that are so important to you, you cannot die without telling.” Every story that’s told, someone couldn’t die without telling, and it’s my job to either help tell that story, create that story, or be that story. And I truly can’t think of a better way to make a living.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world: