Q&A: Writer Charles Soule on the Roads Taken and Not Taken

The STAR WARS: THE HIGH REPUBLIC architect discusses his unusual journey to becoming a comic book writer and author

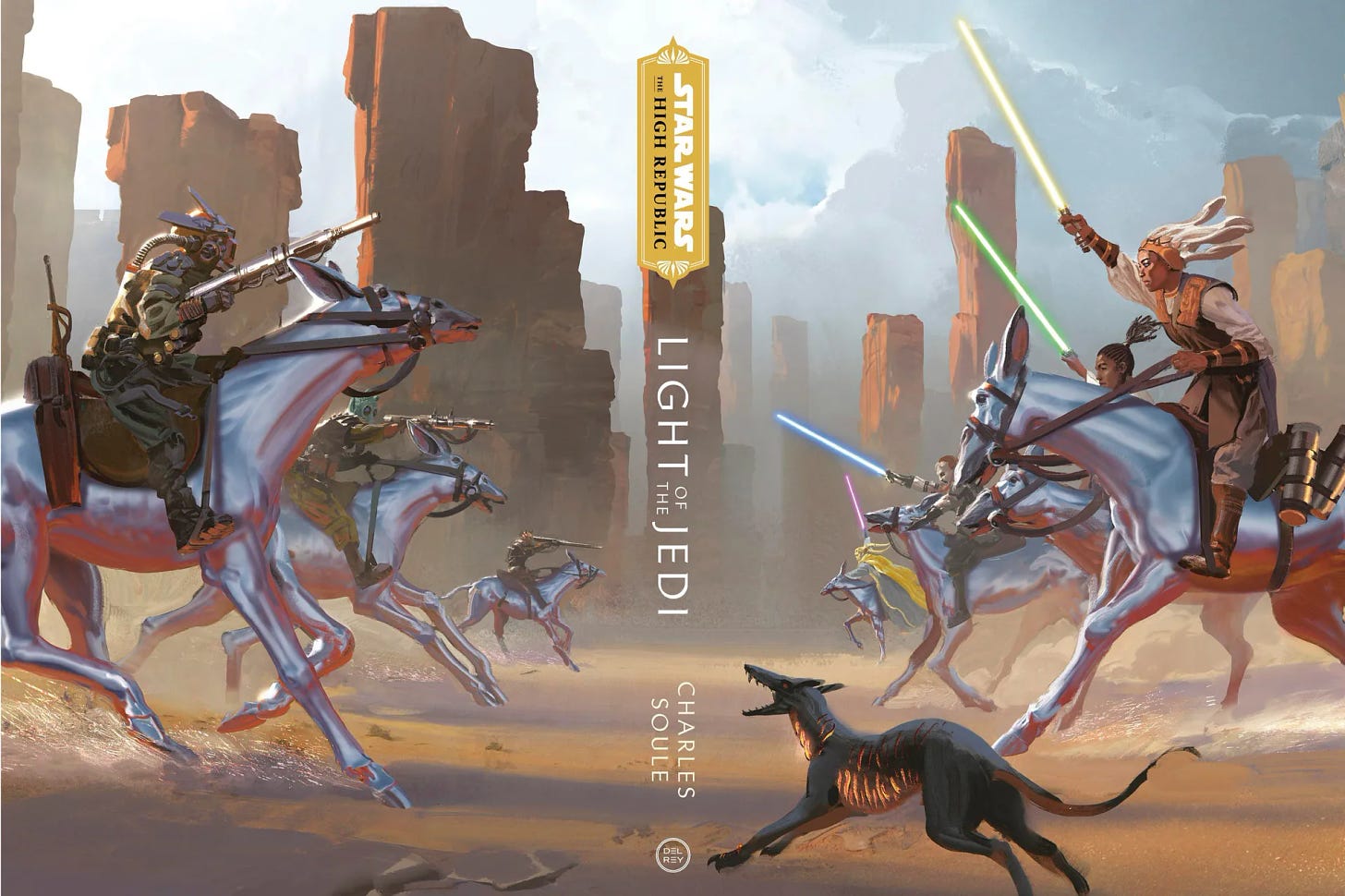

Former lawyer. Occasional musician. Comic book writer. Novelist. Charles Soule has seemingly done it all. I first discovered his work in comics, where he began to really make a name for himself in the teens. He hopscotched between super-hero titles for DC and then Marvel, turning out creator-owned titles along the way, before his first trip to a certain galaxy far, far away. STAR WARS comic after STAR WARS comic followed until he was eventually invited to become one of Lucasfilm’s architects of STAR WARS: THE HIGH REPUBLIC - a multi-phase, multimedia project that spans 500 to 100 years before the Prequels and is set centuries before the fall of the Old Republic. If you’re an avid 5AM StoryTalk reader, I’ve had one of these artist-on-artist conversations with another such architect: Daniel José Older. Like Older, Charles also writes novels. In fact, he wrote the first in THE HIGH REPUBLIC series, THE LIGHT OF THE JEDI, but that was preceded by two set in his own worlds and has since been followed by another of his own, THE ENDLESS VESSEL, which was published last year.

Another way to sum all of this biography up is: I was extremely excited to geek out with Charles after our mutual friend

(also a former guest of this interview series) introduced us.For aspiring and emerging storytellers, there is a great deal to learn here from Charles’s approach to developing stories and the differences between writing for yourself and writing for a brand. For those who dream of breaking into the comic book business, there is a lot here for you, too.

COLE HADDON: Let’s start with a question a bit out of left field: what was the last piece of art you experienced, not based on any IP, that inspired the kind of passion in you that, say, STAR WARS did when you were a kid? That made you just want to make cool shit.

CHARLES SOULE: I’m not sure this is exactly the answer you’re looking for, but I have a whole huge music side to my creative life that I don’t talk about much publicly - or do very much with publicly anymore. The writing has grown to swallow so much of my time that it’s hard to find space to put music out. I used to be in a bunch of bands in NYC, and I’ve got a lot of experience under my belt as a guitarist, composer, singer, arranger, etc. The skills are still there — I’m working on a weird new record now based on one of my comics, kind of a concept album thing — but the idea of getting a band together, rehearsing them, going out and playing live…it would be hard to wrangle.

So, with all of that in mind – I see a lot of shows. Being in NYC gives me the opportunity to see just about every act in the world since they all come through eventually. In particular, I’m a big jazz guy. I play it, know the history, listen to it a lot and see folks live as often as I can. There’s a guitarist named Julian Lage who has grown in prominence lately, and I caught a set of his not long ago at the Village Vanguard - historic jazz club in the West Village, arguably the most famous jazz club in the world. I am an accomplished guitarist — I’ve played everything in every style, pretty much — but this guy blew my mind in a way I wasn’t sure a guitarist still could. He was doing things I couldn’t really parse, and it was pretty damn inspiring. It reinforced the idea that there’s always another level, there’s always another place to go – with the guitar, with writing, with everything. I was deeply impressed.

CH: I love this answer. Let’s stick with the music side of your identity for a moment before we get into some of your other backstory. Do you think you could’ve been equally happy forging a career for yourself as a musician as you’ve been writing?

CS: Absolutely. I loved having bands, rehearsing, forging that camaraderie, performing onstage. Composing, being in the studio, learning songs, arranging - I realize I’m just listing the things professional musicians do, but I really did love all of it. The only thing I didn’t love as much was the intensity of the New York City music scene – incredibly competitive on many levels, from stage time to the musicians themselves. There are only so many good drummers, so many good bassists, etcetera, and they all get pretty booked. Wrangling a band into shape and making sure that organism was properly fed and sustained — with rehearsals, gigs, money, fans — is a massive job, which I just didn’t have time to do the way I wanted once I graduated from law school.

CH: I can imagine.

CS: When I think back on that time, though, I ended up doing a lot of the things to build my writing career that I would have done for my musical career. New tools were coming online — literally — for self-promotion, etcetera, that I’m pretty sure I would have been able to use to successfully to build a following. The problem was that you have to get out there, you have to play gigs, and in order to play gigs, you need to rehearse the band - and all of that requires a flexibility in schedule that was really hard to pull together as a young attorney.

Writing, though, I could do on my own, in the gaps in my schedule that would allow it. All I really needed was the drive and commitment – which I definitely had.

So, would I have been as happy doing music as writing? Yes, but, I’m also envisioning a successful path in music, where I had a well-known band and a studio career and was making a good living. That’s far from guaranteed. Would I be happy as a failed musician, someone who gave it their all but never made it and ended up taking out a loan and starting a studio or buying a little bar or just left the scene entirely? I doubt it. It’s incredibly difficult to succeed as a creative person, especially the way I’ve done it, largely on my own terms. I’m sure there could be other paths for me – but I’m pretty thrilled with this one.

“Writing, though, I could do on my own, in the gaps in my schedule that would allow it. All I really needed was the drive and commitment – which I definitely had.”

CH: Let’s talk about this one then, the writing of it all. I listen to a lot of jazz. So much of it can be improvisational. You feel like something unpredictable is happening as a result, something that feels more emotionally driven than composed. Of course, that’s the illusion, right? The musicians mastered their craft, so that improv — that “spontaneous” creation — is the natural result. What I’m getting at is, what kind of storyteller are you today? Do you believe in strict structure as you create, or do you let your craft — your careful study of it — unconsciously guide you as you pants your way through a story?

CS: I build out a set of rules and structures in a story — or deeply understand them for pre-existing universes like Star Wars or Marvel/DC stuff — set a loose target for the story’s themes and endings and go.

CH: Can you give me an example?

CS: I just had a graphic novel out called EIGHT BILLION GENIES, created with my very good friend, superstar comics artist Ryan Browne. The premise there was that everyone on Earth gets a genie and one wish at the same moment. All those wishes/desires start to spin out and clash with each other, and we follow the world over the next eight centuries to see what happens. I had an elaborate set of rules as to how it would all work – how the genies acted, what they wanted, who my eight characters were on Page 1, and a rough idea that the story would culminate with the very last wish being wished. Beyond that, though, a lot of it was filling in things as I went.

CS (cont’d): Your “improvisation is actually just high-level mastery, musical magic that’s actually technology beyond our conscious understanding” analogy is apt for my writing process — more apt than I’d actually say for jazz improv — because what I think I do is let my brain sink into the structure of the new world I’ve created. My subconscious can toss up story ideas and character arcs and zig-zags that seem like they’re out of nowhere, but are really a natural result of imprinting the underlying structure on my mind. It feels mysterious, but it’s really not.

The trick is to make sure I give myself time to let all that structure marinate before I try to work on the story. If I try to write before I’m really ready, it feels like pushing a boulder up a hill.

“The trick is to make sure I give myself time to let all that structure marinate before I try to work on the story. If I try to write before I’m really ready, it feels like pushing a boulder up a hill.”

CH: This idea about letting structure marinate before you start to work on the story echoes an experience I’ve been having in my own process. Early in my career — and this was primarily as a screenwriter — I had an idea that excited me and sounded like something I could find an employer to pay me for. But there was a speed to that process that ultimately handicapped ideas because my employers wanted what amounted to immediate results. In the past four or five years, I’ve found I just let these ideas sit around until nothing about them feels forced anymore. They reveal themselves on their own terms, in a manner. I think my partners sense that these days, too, how much stronger the work is as a result. Of course, what I’m describing is for my own creation, as EIGHT BILLION GENIES is yours.

CS: One of my little writing mantras is, “You don’t have all your good ideas at once.” That’s got a corollary, too, which is, “You can’t have all your good ideas at once.” The process requires time, connections both conscious and unconscious.

CH: I’m curious how this process of yours changes when working in other people’s sandboxes, such as, as you said, STAR WARS or DC and Marvel books. There’s a timeline there that obviously must be met.

CS: Right, of course. I think that both being an attorney and then working for Marvel and DC trained me up very quickly to work like lightning. When it’s my own stuff, I really take my time and build it and make those connections I mentioned, but for licensed work, a ton of that structural stuff has already been done. My licensed work is generally with characters that have been around for at least forty years – some almost a hundred, when you’re talking about Superman or Batman. So, I can come up with a central idea I think is cool – or scary, or exciting, or whatever I’m trying to do – and then plug it into the existing world. Those go really fast. I’m known for my speed, in fact, and I think it’s been a big part of being able to build a career in the business.

CH: Let’s step back for a moment. You didn’t begin your adult life — if that’s what we call careers — as a professional artist. Why law?

CS: Why law? Because I got into Columbia Law – at the time, the number-three law school in the United States. There’s not much more to it. It felt like the opportunity presented was too vast not to take advantage of it. They admitted like 250 people that year, and a Columbia degree pretty much guarantees steady employment at a great — depending on how you define “great” — law firm immediately upon graduation. If you value credentials — and not everyone has to, everyone’s path is different — it’s one of the inarguable ones inside or outside the legal profession.

That also happened at a time of great turmoil in my personal life. My mother was sick with the cancer that took her away not long after I started law school, and she viewed the Columbia admission as sort of a relief – “at least I don’t have to worry about how you’ll do after I’m gone” kind of thing. I have three siblings, and she was focused before she passed on trying to set everyone up for the future as best as she could.

Those two things combined to create Charles D. Soule, Esq. I was good at being a lawyer. I had my own practice within four years of graduation and built it steadily over more than a decade until I shut it down to become a full-time writer. I could have stayed in that career for the rest of my life and done well for myself. It just wasn’t who I was, and I knew that from the moment I started work at my first law firm after graduation.

CH: Would your mother be surprised by the fact that you’ve become a writer of comic books and author of books?

CS: I don’t think my mom would be surprised about anything I’ve achieved. I don’t think it would be the path she would have picked for me. Parents want success for their kids, but they also want security, and if they had to choose one or the other I think they’d pick the latter. She was always a huge booster for me. My dad was, too. They both had a practical streak, and some of the choices I’ve made probably would have made them a little nervous, but I didn’t ever jump off a cliff professionally, either. I scaled my law practice down as I scaled my writing up rather than just shutting the doors one day.

CH: I’m always fascinated by beginnings. The why of things, but also the how. How many other attempts preceded that fortuitous turn of events? How did you settle on this idea? And so on. So, tell me about STRONGMAN?

CS: That’s actually a really interesting question. I started trying to be a writer by writing a novel just after law school. It’s called THE LAND OF TEN THOUSAND THINGS, and it’s in a drawer - a folder on my hard drive, technically, but still. It’s a historical fantasy novel set in 400 AD China. I wrote it in longhand on subway rides and late at night after getting home from work – very romantic. I had a narrative in my head about the way it would all work for me. I’d write this novel, get an agent, sell it and be able to quit the law. It didn’t work out that way – I made it all the way to the “sell it” part and then the train stopped, at least on that book.

I didn’t stop, though. I started working on my second novel, which eventually became THE ORACLE YEAR, and started investigating comics as a pivot without as many barriers to entry as novel writing. Crucially, you can sell a comic series or graphic novel on a five-page sample of the final, lettered art plus a one-page pitch document. The amount of effort I needed to invest in seeing if a comic project would “go” versus writing an entire novel was reduced by many orders of magnitude.

CH: Okay, I’m finding this logic all very fascinating. I feel like I need you in my life twenty-five years ago. Please, continue.

CS: I did that for about five years, during which I learned the craft of comics, but also learned about the business of comics and built my network - just as important! Eventually, I had my first graphic novel pitch accepted by a small but wonderful publisher — SLG, aka Slave Labor Graphic — that served as a launching pad for many notable creators down the road. That was STRONGMAN, a 108-page graphic novel about a washed-up old luchador who decides to try to recapture his glory days by investigating crime in his NYC neighborhood. It was drawn by Allen Gladfelter, and I’m still very proud of it.

CH: How was it received?

CS: The book barely sold. There was no advance, it was completely self-funded, and I think I made $138 from SLG. That was fine, though, because I was also selling the book at conventions and ended up making my money back through hand-selling copies one at a time for $10 each. All of those hours at the tables in conventions all over the country were my version of a band going on the road in a beat-up van. I met so many people, learned so many things, all of which helped me climb the ladder to eventually get noticed by DC and then Marvel.

“All of those hours at the tables in conventions all over the country were my version of a band going on the road in a beat-up van.”

CH: There was a sequel to STRONGMAN, wasn’t there?

CS: The second book, STRONGMAN: OAXACA TAPOUT, is a significantly longer sequel, about 148 pages, also beautifully drawn by Allen Gladfelter. I initially produced it for SLG, but when the thing was almost done, it became clear that they didn’t have the resources to publish it even at the level they did for STRONGMAN. This is not a slam on SLG. They’re awesome and gave me my shot and probably lost money on STRONGMAN Volume 1. It was a tough time in comics — this was around 2010, which was a tough time financially for everyone after the 2008 banking collapse — and I don’t blame them. But what that meant is that I ended up completing STRONGMAN Volume 2 and never releasing it. I printed a run of about twenty-five copies essentially for myself and reviewers, and sold them at conventions - for $20, I think. I’ve thought quite a bit about releasing it now — doing a Kickstarter or something to make a new deluxe edition of both stories together — but, as of yet, I haven’t gotten around to it.

CH: We all have so many of our babies hidden away in drawers or computer files somewhere. You’ve mentioned a novel and a comic book series now. Do you have many others you poured so much of yourself into and how does it feel having these secret children out of there? Can you ever truly let them go?

CS: I don’t have too many things I’ve fully worked through that haven’t been released, which is nice. STRONGMAN VOL. 2, that novel - but beyond that, it’s not a ton. Four screenplays, but I put screenplays in their own category because almost none of them ever become anything, for anyone, even if they’re sold or commissioned. Some short stories, and a fully-written script for a graphic novel that’s never been drawn. I do, however, have a lot of quite fully fleshed-out story ideas - treatments, I guess you’d call them, but they have beginnings, middles and ends. You could read them and get a good sense of the idea. Those, I hang on to, because bits and pieces often get reworked and used elsewhere. I don’t usually go back and actually relight the fire on an old story idea – but there can be gold in them.

CH: Okay, so you’ve written hundreds of issues of comic books since your first comic book was first published almost fifteen years ago. That’s a lot of opportunity for growth as a storyteller. But with that growth quite often comes the death of ignorance – ignorance that leads to more intentional, but usually unintentional experimentation and rule-breaking. Looking back from this moment, I wonder if you can reflect on the writer you’ve become and, if you’re up for it, what you might’ve lost on the journey?

CS: This will not surprise you based on some of the things we’ve already talked about, but I think of my writing as an instrument I’ve learned to play at a pretty high level. I can shortcut and shorthand and make things work in plots and with characters I’d never have been able to see, much less pull off, back in the STRONGMAN and LAND OF TEN THOUSAND THINGS days. I am a pro. I can whip up a comic script that’s surprising and fun and cool and in-universe and all the other things it needs to be almost without thinking about it. But, of course, I am – it’s just the subconscious muscle memory doing a lot of the heavy lifting. Hundreds of stories preceding the current story, each making it a little easier to make the tale work. It’s exhilarating.

But the thing I think has been part of my writing since day one is my story sense - my ability to just feel whether a story works in whatever its current incarnation might be. Do the characters track, does it feel balanced, does it build properly, things like that. To continue with the musical metaphor, it’s being able to tell whether a story is “in tune.”

CH: I like that description a lot.

CS: My story sense is like an internal tuning fork, and it’s always been there for me. What’s evolved is my understanding of the things I can do in a story that will take it to new places without making it discordant and jangly. I can take leaps, I can do weird things with structure, and it’ll all still work. Baby Writer Charles wasn’t capable of seeing – or hearing, really – things like that.

I get the little suggestion that hyper-experienced writers aren’t “punk” anymore, so to speak, but I guess I just don’t feel it that way. My newest novel THE ENDLESS VESSEL is as formally weird as anything I’ve ever done. EIGHT BILLION GENIES is a bizarre mix of formal structure and completely gonzo storytelling. I don’t feel like I’ve lost anything – though creators aren’t always their own best critics, so who knows?

“My story sense is like an internal tuning fork, and it’s always been there for me. What’s evolved is my understanding of the things I can do in a story that will take it to new places without making it discordant and jangly.”

CH: I think what I hear many artists talk about is how experience and success can cause one to make unconscious or even conscious decisions that amount to “playing it safe”. Perpetuating and growing a career can trump – for some – the audacity they might’ve embraced when “breaking in”. It’s not true for everyone, but it’s a challenge for some and hearing how others combat it is always useful. I think I certainly had to deal with this for several years, as I tried to keep work coming in, and only really confronted how far I’d drifted from the purity of creation when I started writing my debut novel back in 2019.

CS: My hope — and I’m not quite at the point where this has happened — but my hope is that someday I’ll be successful enough that I don’t have to think about the commercial considerations of my work at all. I can think of artists who had a large enough success at some point that they could really push – themselves, their medium, all of it. Getting to that place of complete fearlessness is hard, though.

CH: Can you contrast your comic book work with writing books? Specifically, the fiction you originate – such as THE ENDLESS VESSEL. For me, fiction provided me a route to creative freedom. A depth of imagination that film and TV are largely disinterested in. Limitlessness, I think I would even say. What does writing a book give you that writing comics doesn’t?

CS: Total control? With a book, or any prose piece, it’s just me and the words and the reader. I control every aspect of the experience, and can direct readers’ attention exactly where I want it to go. I think of it like a film director who’s pointing the camera at the spots they want, crafting the shots in a particular order to create the emotional response they’re looking for. I can go macro, micro, whatever I need to do. Comics can do that too, but I’ve got another mind there, another point of view I’m working with. I can still “call my shots,” but the way they end up looking in the final project isn’t entirely up to me. I generally don’t ask my comics collaborators to do highly precise and specific shots or layouts – I give them the option of crafting sequences how they want to do them. That’s fun because it creates results I could never have anticipated, but it also means I save the hyper-focused micro-managing of creative moments for prose. Both have their good points!

CH: Okay, we’ve tackled the early years of your writing career and, I suppose, for lack of better words”, how you made it. We’ve covered a lot of craft along the way. But as a kid who grew up on STAR WARS, who read far too many STAR WARS books along the way, I need to ask – how much fun is it playing around in a galaxy far, far away?

CS: Oh, it’s an absolute blast. I’ve been doing it pretty much non-stop since 2015, with much more to come. I think when all’s said and done, I’ll have — at least — a decade of my creative life spent working in my favorite fictional universe, often at a pretty high level. STAR WARS is awesome to me – it’s an awesome thing, and I still get a huge rush from getting to work on stories with lightsabers or Jedi or Darth Vader, much less some of the other cool things I’ve gotten to do in that universe like creating the High Republic era alongside my fellow architects. STAR WARS has given a lot to me in my life, and it feels good and right to be giving something back to it.

CH: Final question, my friend. It’s a fun one on the way out the door for someone who’s played around in the STAR WARS world so much. You can climb into a DeLorean and go back in time to change one thing in any of THE ORIGINAL TRILOGY films. Basically, you can Special Edition one thing and nobody will ever know it was you who meddled with the films, for better or worse. What are you going to change?

CS: [Laughter] This is a tricky one, because I’m sort of in that position to some degree with the work I do now. If there’s something I think needs some extra explanation or shading, I can often provide it within a comic or a short story – I have a lot of opportunity in the STAR WARS world (and I don’t take it for granted!) If I had to change one thing, though, I think I would adjust Obi-Wan’s line in A NEW HOPE about the Jedi being the guardians of peace and justice in the Old Republic for a thousand generations. A thousand generations is like twenty thousand years, if not more. That is a long time, and makes certain storytelling prior to the Skywalker Saga a little complicated. So, I’d change it to something like “a thousand years” or even “for many generations” just to open up the space a little for, uh, my own stories. Very much a Charles Soule problem.

You can read more about Charles Soule and his latest book, THE ENDLESS VESSEL, here.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Great interview! I loved how he described the interplay between structure and "improvisation."

A great interview with Charles! I have so many of his Star Wars comics (he basically has his own pocket of storytelling to rival any other Star Wars creator besides Lucas); it was great to learn more about him.