Q&A: Showrunner Marc Guggenheim Opens Up about the TV Series That Changed His Life...and Broke His Heart

The "ARROW" creator goes in-depth about the iconic series that made him the person and storyteller he is and how rebooting it traumatized him in unexpected ways

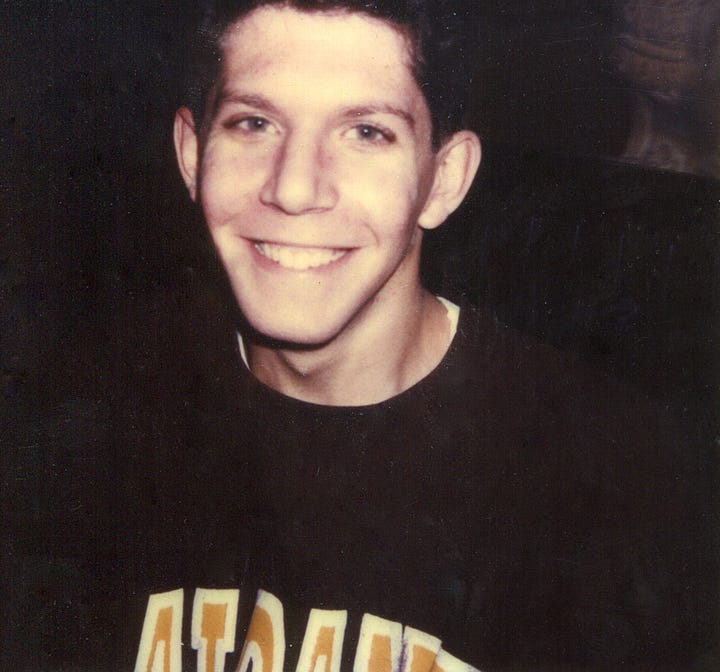

Marc Guggenheim was hired by Warner Bros. to rewrite the first screenplay I ever sold in Hollywood, which is how the two of us first crossed paths back in 2010. On my end, I was keen for some professional tips from someone whose career was going so right; his name seemed to be a regular fixture in the trades at the time, though perhaps nothing was as impressive to me as the fact that GREEN LANTERN1 (2011), a script he co-wrote, had just been greenlit by WB (this was before he saw the end product and began apologizing for it). On his end, Marc was interested to hear how my experience on the script he was about to rework had been (in short: as far from good as possible). Our dinner — which involved several glasses of beer and BBQ, if I recall correctly — ended with him picking up the bill and me insisting I would pay the favor back when I was hired to rewrite him. While that’s yet to happen, the end result of our professional meet-up is a friendship that’s lasted well over a decade.

If Marc’s name doesn’t ring a bell for you, his work probably does because he’s written and/or produced hundreds of hours of television at this point in his career, as well as had a handful of films hit the big screen. Perhaps most significantly — culturally speaking — he co-created “ARROW”2 for the CW. It premiered in 2012, and its success spawned what became known as the Arrowverse — an interconnected world of TV series based on the DC comic book universe. Amongst these was “LEGENDS OF TOMORROW”3, which Marc also co-created. After close to a decade on the job, he stepped away from the world he helped to build to pursue other opportunities, none more important to him than bringing a seminal television series in his life — “L.A. LAW” — back to TV screens.

Marc agreed to have a conversation with me about his career, but my hope was to use this as an opportunity to explore the outsized role I knew “L.A. LAW” had played in his development as a human being and artist. This inevitably led to us discussing the deeply traumatic experience that the “L.A. LAW” sequel ultimately became for him. I’m immensely grateful to him for letting me in, but also for providing other screenwriters — at all levels — a glimpse at the creative heartache that can come for us at all stages of our careers.

COLE HADDON: I’ve had all kinds of conversations with artists as part of this interview series now, but you’re one of the first that involves getting to know you and your work better through the lens of a singular piece of art that made a huge impact on you. For you, I think it’s fair to say “L.A. LAW” played a pivotal part in not only the adult you became, but also the artist you evolved into. Created by Steven Bochco and Terry Louise Fisher, the now-iconic legal drama premiered in 1986 when you were only sixteen years old. Tell me about how you discovered it and what your first reactions to it were.

MARC GUGGENHEIM: What a great idea. No one’s ever asked me about “L.A. LAW” before. It’s strange to consider the question of how I first discovered and reacted to it. I have an almost-encyclopedic knowledge of the show, but have horrible recall for details of my own life — and those two are very much in conflict with each other given your question.

CH: I empathize. My childhood is a complete blur to me, but I can walk you through every season of “BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER”.

MG: My best recollection is that I happened to have stumbled upon the second hour of the original two-hour pilot. I believe it was broadcast on a Sunday night. The show ran for a few episodes on Sundays before moving to its ultimate home on Thursday nights at 10PM. Because I came in “late”, as it were, I remember being a bit confused. But the scene that really grabbed me was when Arnold Becker takes his client, Lydia Graham – if I’m remembering correctly – out to a public lunch so he can show her photographs of her husband with another woman without her making a scene. At least, that’s Becker’s theory. Lydia ends up making a scene anyway, storms out of the restaurant, and Becker, wholly nonplussed, asks the waiter what they have for dessert.

And I was in!

It would be perhaps a year before I would get the chance to watch the first half of the pilot on VHS – yes, I’m old – but I just kept going with the series, getting increasingly sucked in with every episode.

“L.A. LAW” was my introduction to what would become the modern one-hour drama. I still loved episodic shows like the ones Stephen J. Cannell was producing, but going from self-contained episodes to ones with subplots and ongoing stories was like going from black-and-white to color.

CH: And why do you think that was beyond general entertainment value?

MG: I didn’t know enough – anything, really – about writing to know that it was the writing that ensnared me, but that’s very much the case. I was also taken by the characters and this glamorous, sun-kissed world – I grew up on the comparatively cold and grey East Coast – they inhabited.

I grew up with shows like “THE SIX MILLION DOLLAR MAN” and “THE GREATEST AMERICAN HERO” – for example, episodic shows with thing characterizations and not much in the way of ongoing storylines. I didn’t get into shows like “HILL STREET BLUES” and “ST. ELSEWHERE” until much later, so “L.A. LAW” was my introduction to what would become the modern one-hour drama. I still loved episodic shows like the ones Stephen J. Cannell was producing, but going from self-contained episodes to ones with subplots and ongoing stories was like going from black-and-white to color.

CH: I don’t think I realized that it was “L.A. LAW’s” serialized nature that was part of what grabbed you. I suppose it’s fair to say it was so defining for you because it revealed to you what the potential of television really was?

MG: Absolutely. Standalone episodes were just shorter stories, “mini-movies”, albeit without the production value of features. But once things became serialized, it really demonstrated what television could do that movies can’t, namely, tell a long-form story.

CH: I still enjoy the simplicity of the television I grew up with. Because all the characters primarily seem to exist in a world where there is no past or future, just what’s happening in that episode, so much more screen time is freed up to spend on pure plot instead. If you’re watching a cop show or medical procedural or something action-packed like “THE GREATEST AMERICAN HERO”, that can be incredibly satisfying. It also demands nothing of audiences except having a good time.

MG: I tend to look at the difference a bit in terms of genre. “GREATEST AMERICAN HERO” was very much a superhero adventure show. Even a show like Cannell’s “THE A-TEAM” is a very heightened action show. But what you’re talking about with “L.A. LAW” is a much more grounded type of storytelling. And because the stories are more realistic, the characters become more realistic as well. And I will say that part of “L.A. LAW’s” appeal for me was that it wasn’t just depicting the law in a cool and aspirational way. It was doing the same for Los Angeles itself – which is actually kind of ridiculous when I look back on it because the production rarely left the soundstage confines of the courthouses or offices of McKenzie Brackman.

CH: Serialized storytelling was, of course, far from novel when “L.A. LAW” came along. Novels had obviously seen many characters return in sequels, changed and ready to grow more unlike procedural television for most of its existence; and the proliferation of sequels in the seventies and eighties made even filmic experiences potential chapters in a bigger story. But in many ways, I can’t help but feel like comic books embraced this kind of ongoing narrative in the eighties better than any other medium. You’ve written your fair share of comic books at this point, but were you obsessed with them as a kid, too?

MG: Oh yeah. I was obsessed with comic books before I was obsessed with anything else. And comic books were telling long-form, serialized stories far earlier than television was.

CH: Do you think something like “L.A. LAW” made more sense to a sixteen and seventeen-year-old kid because you had already been hard-wired to some degree for it through comic books?

MG: That’s an interesting question. I’m sure that’s the case. By the time “L.A. LAW” came around, I was already well-versed in comics like THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN, THE NEW TEEN TITANS, and UNCANNY X-MEN, all of which had highly serialized elements if not outright soap opera.

CH: You recently kept me company on the phone during one of my bushwalks here in Australia, and during that chat, you made a statement I didn’t interrogate at the time. You said you went to law school because of “L.A. LAW”. Can you elaborate on that?

MG: Well, I think it’s more accurate to say that I became interested in the practice of law – specifically, litigation – because of “L.A. LAW”. I was very much seduced by the aspirational way the law and litigation were depicted. I had been bullied a lot as a kid – and was still being bullied when “L.A. LAW” premiered – and was very interested in the idea of there being an organized and fair system for the redress of personal wrongs. That’s why I went into civil litigation.

I was very much seduced by the aspirational way the law and litigation were depicted [on “L.A. LAW”]. I had been bullied a lot as a kid…and was very interested in the idea of there being an organized and fair system for the redress of personal wrongs. That’s why I went into civil litigation.

CH: What inspired you to give up practicing law for screenwriting?

MG: It wasn’t just one thing. I’d started writing in my third year of law school and found that I really enjoyed it. So much so, that I continued to write and hone my craft while I was practicing. Cut to five years later. I was twenty-nine and in my fifth year of practice. At my firm, you could be promoted to junior partner in your sixth year, so I felt that I was quickly approaching the “fish or cut bait” stage of my career. At the same time, the bloom was really falling off the rose for me as far as the practice of law was concerned. I found that, in civil litigation, that “organized and fair system” I spoke about really had more to do with the size of the client’s war chest – how much they could afford, how long they could financially withstand the grind of litigation – than with the merits of their case. At the risk of being reductive, I found that the system that made me want to be a lawyer didn’t operate the way I thought it did.

Long story short – too late, probably – I realized that if I was going to make a go of being a writer, I should do it before I was a partner at my firm [and] before I was thirty and while I was still single and without kids and all the financial responsibilities that come with that.

CH: So, I have to ask. The first stretch of your screenwriting career – we’re talking a decade or so – was spent working on TV series that I would say “make sense” when I look at them through the lens of some guy who became obsessed with “L.A. LAW” as a kid and ended up becoming a lawyer in part because of it. The first series you created was also a legal series, that being “ELI STONE”. But then, there’s a pretty damn dramatic pivot to, as people I can’t stand would refer to them, TV series about men in tights. “ARROW” was the first, which turned into a huge hit. Basically, you helped launch a decade of non-stop DC superheroes on TV. How the hell does a well-established Lawyer Man become a game-changing Superman?

MG: That’s...fair. It went kind of like this. By the time “ELI” was canceled, my writing career had proceeded along two very separate tracks: I was writing non-genre television shows and, at the same time, writing comic books for DC and Marvel. When “ELI” got canceled, I told myself that it would be fun to “cross the streams” and start doing genre television. It wasn’t intended as a permanent switch, just something I wanted to do as my next project. And that next project was a sci-fi show called “FLASHFORWARD” with David Goyer. After that came what I would describe as a “soft superhero” show called “NO ORDINARY FAMILY”. Then there was “ARROW” and I think you could fairly say that – in true archer fashion – I overshot the mark in terms of my original goal.

CH: Well, the end result was momentous as far as I’m concerned. The so-called Arrowverse spawned numerous interconnected series, a sprawling shared universe basically, that’s finally going to wrap up next month with the final episode of “THE FLASH”. We’re talking hundreds of hours of television that brought the DC universe to life during a period when Warner Bros. largely could only work out how to make money off Batman at the movies. More, you did it by staying true to the tone and truth of these characters. It’s a real labor of love, and I’m truly disappointed you won’t be having a hand in Warner Bros’ 849th attempt to launch a DC cinematic universe.

MG: Thanks. I really appreciate that. The truth is, I was a small piece in what grew to become a very large machine. I developed an affinity for the production jujitsu that was required to pull off the spinoffs, but the whole endeavor was really a massive group effort.

CH: If it’s okay to ask, were there any DC characters you tried to incorporate but were told you couldn’t use? I always hoped Warlord would make an appearance. Of all the DC characters I ever hoped to get a chance to adapt someday, he and Adam Strange have always been at the top of my list

MG: It’s funny how much of my recall for these sorts of things just went out the window once I stepped away from the Arrowverse. Yes, there were plenty of characters that we wanted to use or reference or easter egg, but were told we couldn’t for any number of reasons, but I don’t really remember them. I know that’s probably an unsatisfying answer, but the truth is that if one door was closed to us, I would just move on and look for another door.

I will say that I regret not getting the Question into “ARROW” at some point. That just seemed to me to be a no-brainer in terms of fit between character and show, but it’s just one of the things I never got around to.

CH: You officially left the Arrowverse in 2020, which I know was quite difficult after the many years you invested in it. But it wasn’t long afterward that I heard about the “LAW LAW” sequel you were going to be writing with Arrowverse alum Ubah Mohamed. Sequel, reboot, whatever we want to call it. It was an outlandish idea, I thought, returning to the same law firm and many of the same characters you fell in love with as a kid. What was being given that opportunity like for you, given how much the series meant to you?

MG: Oh gosh, how much time do you have? I can’t overstate how important “L.A. LAW” was to me as a show. It would be like me writing a STAR WARS movie, let’s just put it like that. And not just any STAR WARS, but a continuation of the stories of characters I fell in love with when I was six years old. “L.A. LAW” looms that large.

I think what helped was that it wasn’t like a switch was thrown and one day I was suddenly developing a follow-up to “L.A. LAW”. Rather, it was just a series of conversations. First, with director Anthony Hemingway. Then, with Dayna and Jesse Bochco. And finally, with Blair Underwood. But even then, after all those meetings, pitches, and conversations, I still had to pitch the studio and then the network. What I’m trying to say is that I didn’t just dive into the pool. I walked in very, very slowly and step by step.

CH: Was it daunting to step into the shoes of so many characters you loved? What challenges did that bring for you?

MG: It was extremely daunting, yes. But the thing is that to actually do it, you have to – at least, I had to – eventually put that all aside, forget the magnitude of the thing, and just do the work.

CH: A new “L.A. LAW” pilot was ultimately shot and you were kind enough to give me a look at the shooting script. And I have to say, it’s wonderful stuff, my friend. Truly. You two somehow retained the dark sense of humor and the ethical quandaries that come with being a lawyer, but infused powerful new angles through the character of Blair Underwood’s Black partner Jonathan Rollins. There’s a scene on the rooftop of the firm, which you showed me the dailies of, in which Rollins is challenged for the compromises he’s made as a Black man in his career, and it shook me.

It’s a bravura, Emmy-caliber performance by Blair and Ian Duff. And it made a lot of people quite nervous – which is what the original “L.A. LAW” did, so I felt we were in good company.

MG: Thank you. I really appreciate that for so many reasons – not the least of which is that I value your opinion as a fellow creator. And that scene on the rooftop is one of the best scenes I’ve ever been involved with. It’s a shame more people – any people? – won’t get a chance to see the finished product. It’s a bravura, Emmy-caliber performance by Blair and Ian Duff. And it made a lot of people quite nervous – which is what the original “L.A. LAW” did, so I felt we were in good company.

In fact, before proceeding further, to really understand what happened with our reboot/relaunch —whatever you want to call it—I need to offer up a quick primer on the original show. In fact, I’m going to send you a quote for my original pitch to include:

[LA Law] was the first true “water cooler” drama. Amazingly, it was nominated for Best Drama in all of its eight seasons and won four out of those eight times. It achieved this by entertaining the audience, yes, but also by reflecting the issues of the day. It tackled subjects like: euthanasia, gay rights, flag burning ([they] actually burned the flag on camera). [Episodes included television’s] first lesbian kiss, second interracial kiss, and [even] Black Lives Matter, decades before the term was even coined -- depicting the Rodney King riots and an episode where Blair Underwood’s character was arrested for “jogging while Black” in Beverly Hills. LA Law was able to go to these places because it was on the air before it became “impolitic to talk about politics.”

CH: Unfortunately, ABC—for reasons I will never understand—decided not to give it a series order. It’s easy for filmmakers to crow about the good because it’s what pays our bills and perpetuates that luster of success that begets more work, but I think that’s terrible for our mental health. I wonder if you could talk about what this hit was personally like for you given your passion for “L.A. LAW”.

This was a show with a lot of Black and brown faces, arguments about slavery reparations, and a trans/CIS same-sex relationship. It was what I thought “L.A. LAW” would be if it were on the air today.

MG: Quite frankly, it was like a death. It would be one thing if the pilot turned out badly. But it didn’t. I know when I’m involved with a turkey – I co-wrote GREEN LANTERN, remember – and I’m self-aware enough to know when something I’ve done is bad or has fallen short of the mark. This wasn’t that. This was a show with a lot of Black and brown faces, arguments about slavery reparations, and a trans/CIS same-sex relationship. It was what I thought “L.A. LAW” would be if it were on the air today. Unfortunately, such a show was never going to test well with audiences in 2022. Our numbers were “soft” which, truth be told, was better than I’d expected given the subject matter.

All that being said, I’ve come around to the feeling that maybe it’s a good thing our pilot didn’t go.

CH: Really?

MG: My sense of self-preservation isn’t particularly well-developed. If we’d gotten the show on the air, my passion for the kinds of stories “L.A. LAW” used to tell – which could actually be told back in the 1980s – would have probably gotten me into some kind of trouble. I used to joke that if we did “L.A. LAW” the way I believe it needs to be done, I’d get canceled before the show did. Or I would have been forced by circumstance to tone down the show to the point where I would have been betraying what made it special. Either outcome wouldn’t have been good, and, arguably, would have been worse than the show not moving forward.

But to get back to your question, we’re having this conversation almost a year after ABC passed on the pilot. I’m certainly better off now than I was back then. I’m happy in life and with my work. I’m excited about the projects I’m working on – or was working on before the WGA strike. But I’ll never really be the same. As much as I told myself that I was happy just writing and producing an episode of “L.A. LAW”, the “what could have been” will always be like a pebble in my shoe.

Find Marc Guggenheim here on Substack where you should be reading his LegalDispatch newsletter. You can also check out his latest comic book series STAR TREK: ECHOES, out this week.

If this article and the time I spent on it added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is now available from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. Paperback will hit shelves on May 25th. You can order it here no matter where you are in the world:

GREEN LANTERN (2011) was written by Greg Berlanti, Michael Green, Marc Guggenheim, and Michael Goldenberg; story by Berlanti, Green, and Guggenheim

“ARROW” was co-created by Greg Berlanti, Marc Guggenheim, and Andrew Kreisberg

“LEGENDS OF TOMORROW” was co-created by Greg Berlanti, Marc Guggenheim, Andrew Kreisberg, and Phil Klemmer