Q&A with Matt Fraction: The Comic Book and TV Writer on What He's Learned from Letting Go as an Artist

The 'MONARCH: LEGACY OF MONSTERS' co-creator discusses the virtue of crazy ideas, chasing right angles, and the boozy hotel bar debate that changed his life

Dearest readers, I’m going to let you in on a little secret: I rarely sit down for 5AM StoryTalk’s artist-on-artist conversations with anything that smacks of an agenda. Sure, on occasion, there might be an angle an artist’s oeuvre suggests beforehand, but even then, I have no interest in deterring the artist from whatever they feel inspired to talk about. My questions are, for the most part, reactions to their answers and random anecdotes and are primarily informed by my own knowledge of and experience with the creative process and life. In other words, I am consistently as surprised by where these conversations go as you probably are as you read them. This was certainly the case with Matt Fraction, the Eisner Award-winning comic book writer turned TV writer whose first series, the GODZILLA spin-off “MONARCH: LEGACY OF MONSTERS” — which he co-created with Chris Black — debuts this month.

At every turn, I was hit with unexpected replies that involved subjects as varied as woodworking, Park Chan-wook, and LCD Soundsystem. But I don’t think anything could have prepared me for Matt’s recollections of a boozy encounter in a New York bar that transformed how he viewed his collaborations past and future. The profundity he drops here has done its best to detonate so many of my theories about art. I’m still dizzy from it and the possibility I have now experienced something just as transformative myself as a result.

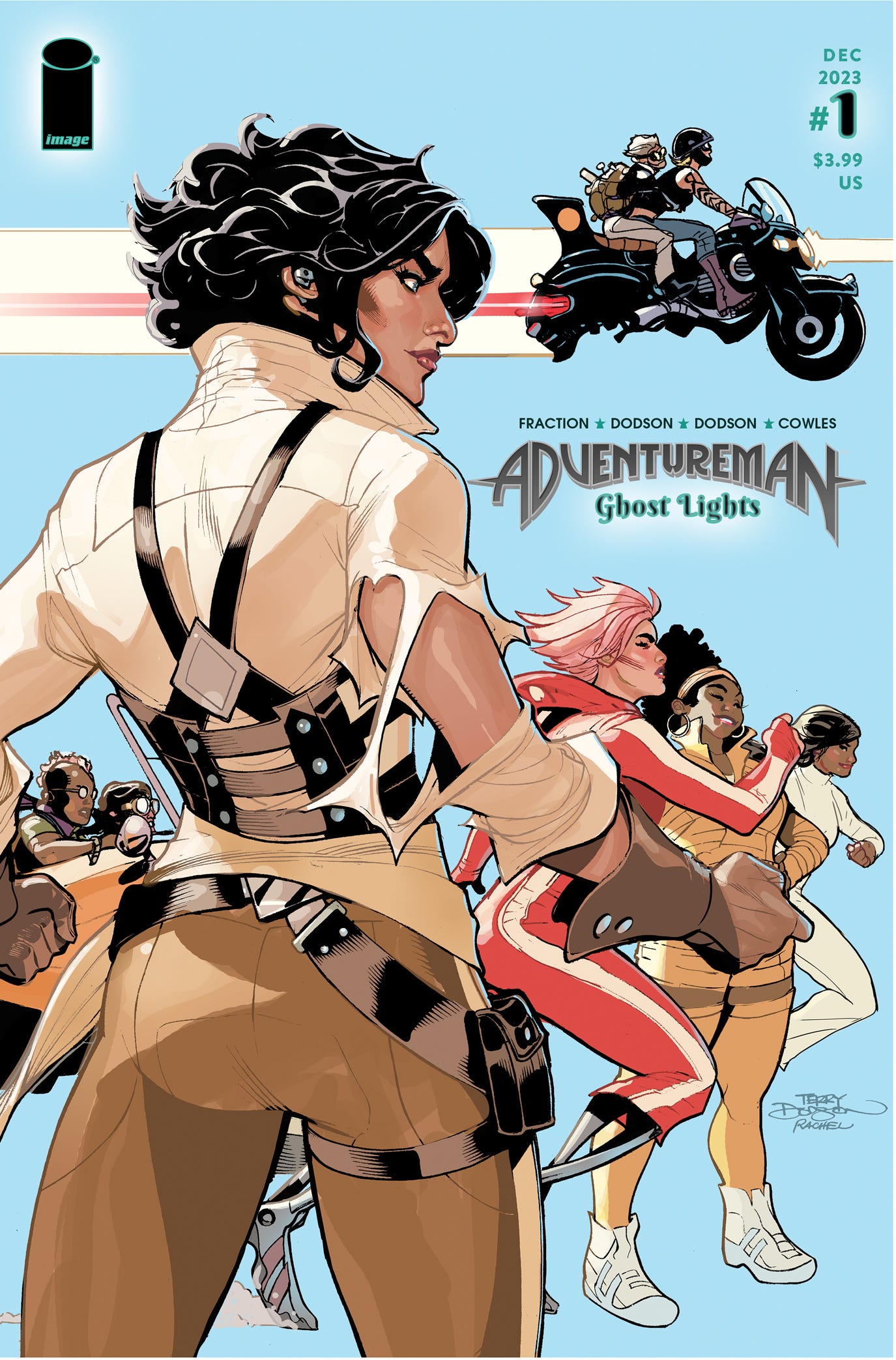

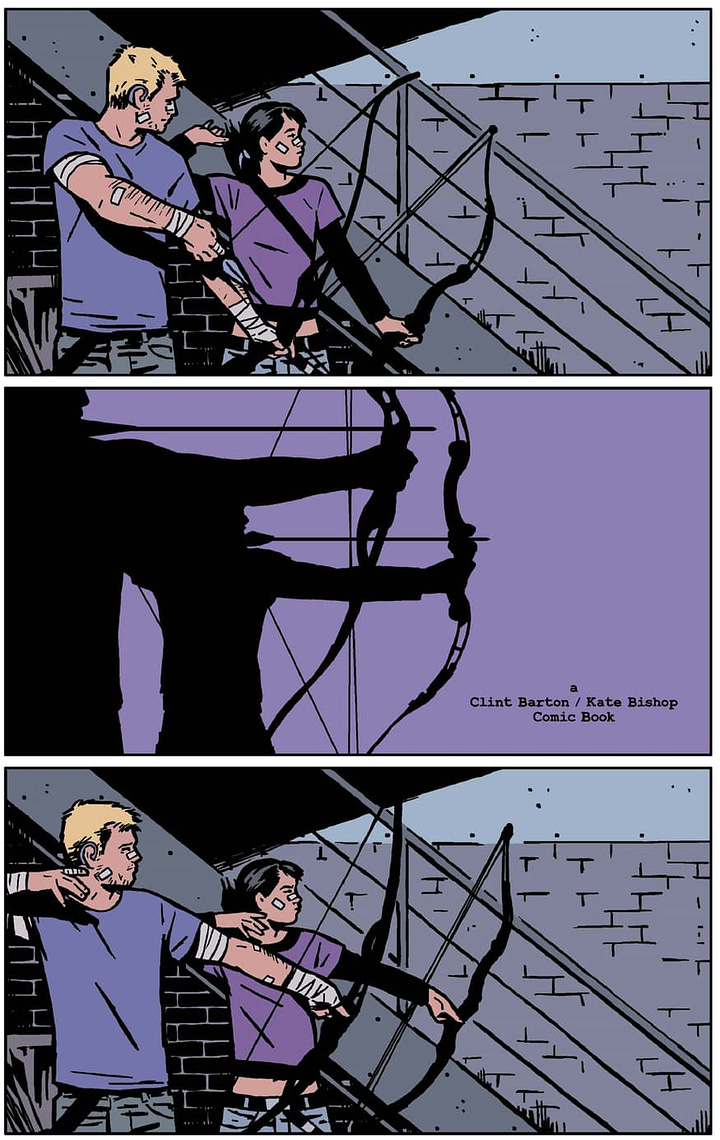

Before I dive into this chat, let’s just lay out Matt’s bio for those who don’t know the ins and outs of it. He’s an incredibly prolific and celebrated comic book writer/creator who counts, amongst his credits as a writer, THE INVINCIBLE IRON MAN, THE IMMORTAL IRON FIST, SUPERMAN’S PAL JIMMY OLSEN, and, perhaps most famously, HAWKEYE - which inspired much of the MCU’s “HAWKEYE” TV series. In addition, he (and many different artists) created independent titles such as SEX CRIMINALS, CASANOVA, and, most recently, ADVENTUREMAN. If that’s not enough, he’s now gone and become a TV writer. We’ll be talking about “MONARCH: LEGACY OF MONSTERS” more in our conversation.

Okay, all caught up? Great, let’s dive in. Prepare to have your mind blown.

COLE HADDON: I wonder if you could tell me the last piece of art you experienced – regardless of the medium – that made you feel like a hack, like you’d never be good enough to do anything like that, and, of course, why.

MATT FRACTION: A couple things come to mind…

There’s a furniture maker named Clark Kellogg who made a cabinet-box he named I Don't Want to Be Destroyed. It’s padauk, ebony, spalted maple, curly maple, and cedar, with brass finishings. It is a profoundly gorgeous and patient piece that radiates care, concern, focus, and a unity of design and form and function that drives me crazy. I am a novice-ass, neophyte-ass, dilettante-ass woodworker and looking at a piece like this – the kind of thing I want very much to make – feels like saying I want to be a ninja-astronaut. I’m trying to learn cabinetry/carcase carpentry, as much by hand as I can manage. Because of time, because of space, because of life and all its vagaries, I don’t get too much regular time at my bench these days. It’d be a minor miracle if I could saw a straight line right now.

CH: An unexpected answer, but a beautiful one – almost as beautiful as that cabinet-box. The other?

MF: The other is, last night I caught the restored/anniversary rerelease of OLDBOY on the big screen and, goddamn. Every choice made in that movie is unexpected, every shot is a surprise, every move dreamlike and surreal but somehow entirely logical and inevitable - to say nothing of the extraordinary violence and… you know…of it all.

CH: That still makes me shiver.

MF: The first time I saw it, it felt like it was boiling my brain in my skull and, twenty years later, it still has that edgy, unpredictable, glorious singularity. And to compare it with last year’s DECISION TO LEAVE, which is so, like, the anti-OLDBOY and could’ve functionally, shot-for-shot, been made by…well, maybe not Hitchcock, but Clouzot or something. Park Chan-wook is just a ferocious talent. And JOINT SECURITY AREA and THE HANDMAIDEN and, god, the guy has range. The trust he has in himself, his ideas, his vision. It takes a kind of courage, maybe. I’d watch that guy shoot Arby’s commercials.

CH: I actually wrote a film for him. We spent close to a year working on it together.

MF: Tell me literally everything.

CH: It was an intense experience, and one I would easily describe it as one of the most creatively satisfying – and challenging – of my career. The project was a feature adaptation of the Japanese novel GENOCIDAL ORGAN by Project Itoh, something of a hybrid between a Hollywood spy thriller and Director Park’s wildly singular instincts. I wouldn’t have expected him to gravitate toward material like this, but there are existential questions endlessly at play in the narrative that excited both of us. Those ideas meant he could operate at a very instinctual level as we developed it. And, Jesus, what a thing it is to watch such a master operate that way.

I found him as intellectual as he is intuitive in his approach. That in itself is not uniquely special. Outside of English-speaking cultures, this is much more normal when it comes to narrative. But with Director Park, what’s dazzling is how well-trained his intuition is. He’s fed it films and literature and philosophy from around the world, then he just trusts it, even if he doesn’t understand why yet. In this way, I found it an incredibly transformative experience, creatively speaking. My novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD, which I started writing not long after Director Park and I wrapped working together, owes a great debt to how creatively freed I felt by observing him.

MF: He’s such a fascinating creative figure to me. I mean, just to compare DECISION TO LEAVE to OLDBOY, on the surface, and it’s hard to conceive they were made by the same person. Until you sit with them both and look at them holistically. I don’t really go in for auteur theory, but his projects all seem so indelibly his.

“I think the experiences accrued by being involved more and more with brilliant artisans and craftspeople way down on the IMDb credits page make it abundantly clear these things are always more than the sum of their parts because of all those parts.”

CH: What about the auteur theory doesn’t ring true for you?

MF: I think the experiences accrued by being involved more and more with brilliant artisans and craftspeople way down on the IMDb credits page make it abundantly clear these things are always more than the sum of their parts because of all those parts. The most singular of visions still have to be realized by people who can summon visions into reality. I mean, whether it’s Kelly Reichardt and her production designer Anthony Gasparro, Kar-wai Wong and William Chang. Like, there’s a reason Wes Anderson’s worked with Sanjay Sami since 2007, right? Wesworld starts with Wes but it’s the crew he’s gathered around him that make Wesworld accessible to the rest of us. I think maybe the greatness of great directors starts with their ability to surround themselves with great craftspeople.

CH: I really appreciate that sentiment and certainly believe it’s true, though maybe not a widely held belief in an industry that elevates directors above all others.

When you brought Director Park up a moment ago, you marveled at “the trust he has in himself, his ideas, his vision.” It was, as I just described, very much what it was like working with him, too. I’m curious, does that sound at all like how you work? If not, where how does your creative process differ?

MF: Very much so, for better or for worse - at least, I hope. There’s a magic moment when, like, I just know all the ingredients on the kitchen counter will make a meal. Doesn’t mean it’s a meal anyone but me will enjoy, but I know I have it.

I can’t necessarily explain how or pitch it — and I fucking hate outlining, which makes me a real joy in the development process — but I don’t want to write about what I want to write. I just want to write the thing. But, like, the best example – and probably the comic I’m most known for – is SEX CRIMINALS made with Chip Zdarsky.

MF (cont’d): Whenever I told someone what the idea was – a woman who stops time when she experiences orgasm meets a man with the same ability, and together they start having a lot of sex and robbing banks – looked at me like I had worms falling out of my mouth. Or like, “Oh, you’ve written superhero comics too long and now you have some nonsense to get out of your system.” But I knew it was something real and true and I just had to ignore the looks and whispers of career suicide and do it.

“I knew it was something real and true and I just had to ignore the looks and whispers of career suicide and do it.”

CH: It’s so difficult to trust that instinct, isn’t it? That drive to be your most authentic self regardless of the consequences.

MF: I came to realize when I don’t trust it, I feel pretty terrible about, like, everything. Physically, I mean. It takes a toll on me I’m just not willing to pay. You know the LCD Soundsystem song “You Wanted a Hit”?

CH: Oh yeah.

MF: I think about a line from that song a lot: “We don’t really do hits.” But sometimes what I do hits, and it’s never not completely weird and wonderful when it does.

CH: Let’s turn backward for a moment, to your secret origin so to say. You’re primarily known as a comic book writer, easily one of the most celebrated in the 21st century. I’m curious, can you remember the first comic book you actually held in your hands and read?

MF: I think so - it was BATMAN #316. Completely bonkers story about a bad guy named Crazy Quilt who forces a doctor to operate on his failing eyes, gets stopped by Batman and Robin, and goes blind. I did a quasi-stand up, quasi-spoken word thing about it once upon a time, including on-stage at San Diego. My pal Chad recorded one of them. I’ll send it to you to include.

CH: I had to look that issue up, and I remember owning it long ago before I started moving around so much that I had to adios my deeper comic collection. I’d forgotten that was Len Wein. Can you remember the first time you tried to write or even illustrate a comic book of your own? I mean the one in the notebook you carried to school and did your secret shit in.

MF: Oh god, it’s one of those things I can’t remember ever not doing. I started off on a fine arts path and kind of fell sideways into writing, but comics were always a part of that. Something about boxes inside of boxes made sense to me.

“Comics were always a thing I did, a thing I made. I’d still be making them even if no one published them.”

MF (cont’d): I remember taking dot-matrix printer paper, separating the sheets, tearing off one edge of the perforated holes, then sewing the pages together through the other strip with yarn so my comics had a kind of binding. Or, one summer making comics on these weird half-sheets of paper, then loaning them out to friends one at a time like library books. I’d keep track on the inside back cover of who was borrowing it in what order and who would get it next.

Comics were always a thing I did, a thing I made. I’d still be making them even if no one published them. I like telling stories with words and pictures, whether they’re drawn or filmed. It all kind of makes sense.

CH: I talked with your pal Ed Brubaker at length about how his voice developed, which is, as you know, a colorful story – to put it mildly. Can you discuss the origination of yours? Hopefully, it involves fewer dead bodies than Ed’s.

MF: People always make fun of the neighbors of serial killers being like, “He was so quiet and pleasant! We had no idea!” Then, you meet someone like Ed and it’s like, oh, okay. Nothing about who Ed is as a person — like, in person — suggests he’s got anything akin to his work anywhere inside him. It’s where and how Ed gets his darkness out.

For me, I’m not so sure? Maybe it’s like being scent-blind to your own house or something, like, I can’t hear it so well. I think the more I realized and trusted that I don’t really do hits, the freer I was from trying to do anything otherwise. Whatever conversation I’m having has become one between me and the work, whatever the work is, and it feels ideal. That I fool people into paying me to do it feels like a bonus, because I’d be doing it anyway.

“I think the more I realized and trusted that I don’t really do hits, the freer I was from trying to do anything otherwise.”

CH: I started this interview by asking you what the last piece of art was that more or less intimidated you, that made you feel inadequate. How important do you think that feeling is to you and your process and how you see your own art?

MF: Not to sound like a podcast cynic or whatever, but the more I do it, the more I really feel like the scary way is always the way I need to go. To get into the weeds of comics a little, which I still consider my primary vehicle—

CH: Please do.

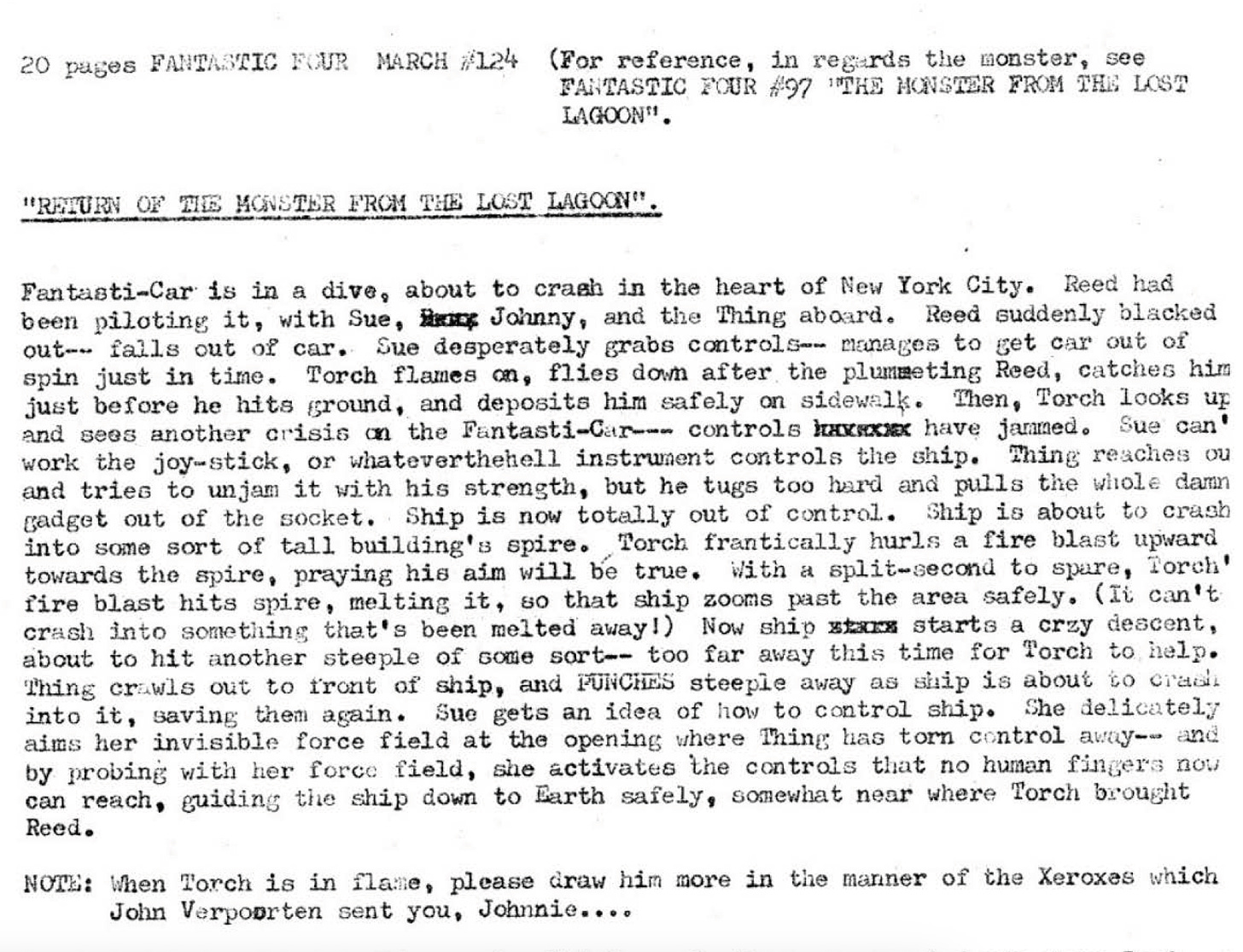

MF: Back in the day when Marvel Comics became Marvel Comics, they were all — for any number of reasons that are totally fascinating, but would only take us deeper into the weeds so I’ll skip it for now — written by Stan Lee. This meant, I think, he was responsible for creating the story for eight books a month, more or less. So, to better navigate his workload, Stan began writing his scripts in a manner that came to be called “Marvel Style” or, if you don’t want to throw a trademark around, “Plot Style”.

Usually — then and now — comic scripts were written much like screenplays or teleplays, with panel descriptions serving as shot/action descriptions, and dialogue underneath. Stan, faced with a pretty gnarly workload, began crafting scripts that were more like what we think of as outlines — sometimes fairly detailed, other times much less so — putting the primary visual onus of storytelling on his brilliant partners like Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, etcetera.

MF (cont’d): So, while Stan might write “PAGES ONE and TWO: The Fantastic Four return from their latest adventure and settle into the kitchen. While Reed and Sue make breakfast, Johnny and Ben bicker until they nearly come to blows,” it’d fall to Jack to figure out what and how to tell that story visually in those two pages. What kind of breakfast? What kind of bickering? Where’s the visual emphasis on this page, what are we looking at and in what order? You can see in Kirby’s originals how he’d break the story down for himself in the margins, with little sentences to remind himself of the flow of panels/shots he’d conceived. Then, once it was pencilled, Stan would go over the art and add dialogue based on what had been drawn. It really breaks down the notion of sole authorship, especially down the road as Stan’s plots could be incredibly brief and vague.

CH: I’m loving this conversation, but how does it tie into the role of fear in your creative process?

MF: Cut to, I don’t know, 2009 or something like that, and I’m in Chicago at BarCon – the inevitable gathering of pros in the hotel bar after a day of Comics convention-ing – listening to Joe Quesada. He was then Editor-in-Chief at Marvel Comics and a protean creator/writer/artist himself, and was winding up Brian Bendis — co-creator of Miles Morales, Riri Williams, Jessica Jones, ad-literally-infinitum — about “the State of Things”. Specifically, Joe was arguing as an artist that, as comics had entered a writer-driven era, comics — or at least Marvel Comics — had lost a degree of visual firepower that had helped make Marvel…well, Marvel. Because, Joe argued, the comics that built the foundations upon which we all stood had been written in Plot Style – meaning they were as much written by the artists as the writers, and while you or I may write the best coming-home-from-an-adventure-and-making-pancakes scene ever put to paper, you or I — or, as Joe was arguing, Brian — could not out-write the hand and eye of artists like Kirby or Ditko or Romita or Buscema.

“While you or I may write the best coming-home-from-an-adventure-and-making-pancakes scene ever put to paper, you or I … could not out-write the hand and eye of artists like Kirby or Ditko or Romita or Buscema.”

CH: This is a fascinating and…damnit, very compelling argument.

MF: While Joe 100% lives for winding Brian up, and Brian was 100% wound up and insisted writing Plot Style wasn’t really writing, that it was lazy and non-committal, I realized, wondering about how I could possibly let myself write that way. It made my stomach hurt a little. It felt like I’d be taking my hand off the wheel of the car or something. It was intimidating in the utmost. So, I decided that, well, fuck it, I at least had to try.

CH: And?

MF: It kicks ass.

CH: [Laughter] Amazing. Come on, tell me more.

MF: It’s maybe the comics equivalent of not directing from the page, almost. I find it 100% more collaborative, more surprising, and the results more visually powerful. Less taking my hand off the wheel, it’s more like taking a trust fall. It feels more like improv or something — yes and-ing back and forth until the printer comes to take the book away — and… and I really love it. It feels as close as I’ve come to feeling like I’m directing since I was in film school.

“I find it 100% more collaborative, more surprising, and the results more visually powerful. Less taking my hand off the wheel, it’s more like taking a trust fall.”

CH: What has been the impact of this on your writing overall?

MF: It’s not the sole way I write comic scripts — it depends on my collaborators and what they prefer, and I tend to write a Full Script more than Plot Style, to be honest — but some of the most successful comics I’ve written, commercially as well as critically at least in my own estimation, were written Plot Style. My version of Plot Style tends to not be any shorter than my full Scripts, but I’m not writing in that manner for efficiency or expediency’s sake. I’m writing that way to fully put my creative trust in my collaborators. I think creators like David Aja, with whom I did HAWKEYE, and Terry Dodson, with whom I’m doing ADVENTUREMAN currently, to be absolute co-authors of those books.

MF (cont’d): Long story long, that’s the event that led me to realize whenever my stomach hurts thinking about something, it’s at least worth examining if it’s hurting for the wrong reasons. And it almost always is. The work is always better than what I’d have done alone. So yeah. The obstacle is the path and all that.

CH: There’s something almost creatively spiritual about how you…I don’t know…let go. You discovered deeper collaboration and creative satisfaction than you might’ve otherwise had – which I will not hesitate to admit is a problem I’ve had when writing comic books in the past.

MF: I guess on some level I’ve always thought that if I wanted to be god, I’d write a novel, but I’m not smart enough to be god and like it when smart clever people make my work smarter and clever…er. The practical reality is, I think — I know — it made me a better, more open, collaborator. I love being surprised by a thing that used to be mine, but now is ours. I love when the thing becomes more than the sum of its parts. It’s all down to trust.

“I love when the thing becomes more than the sum of its parts. It’s all down to trust.”

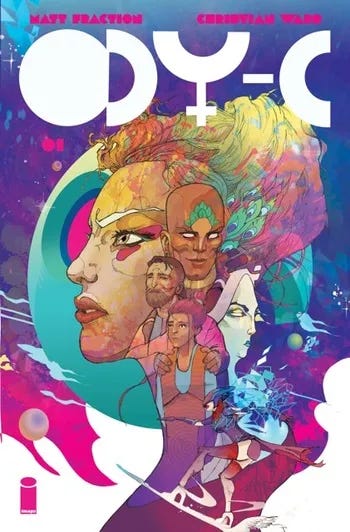

CH: I’ve just finished chatting with artist Christian Ward, whom you co-created ODY-C with based on an idea you had. Did you write Plot Style for him? I ask because, as such a fan of his work — which is so singular, in my mind — I’d love to hear what that was like.

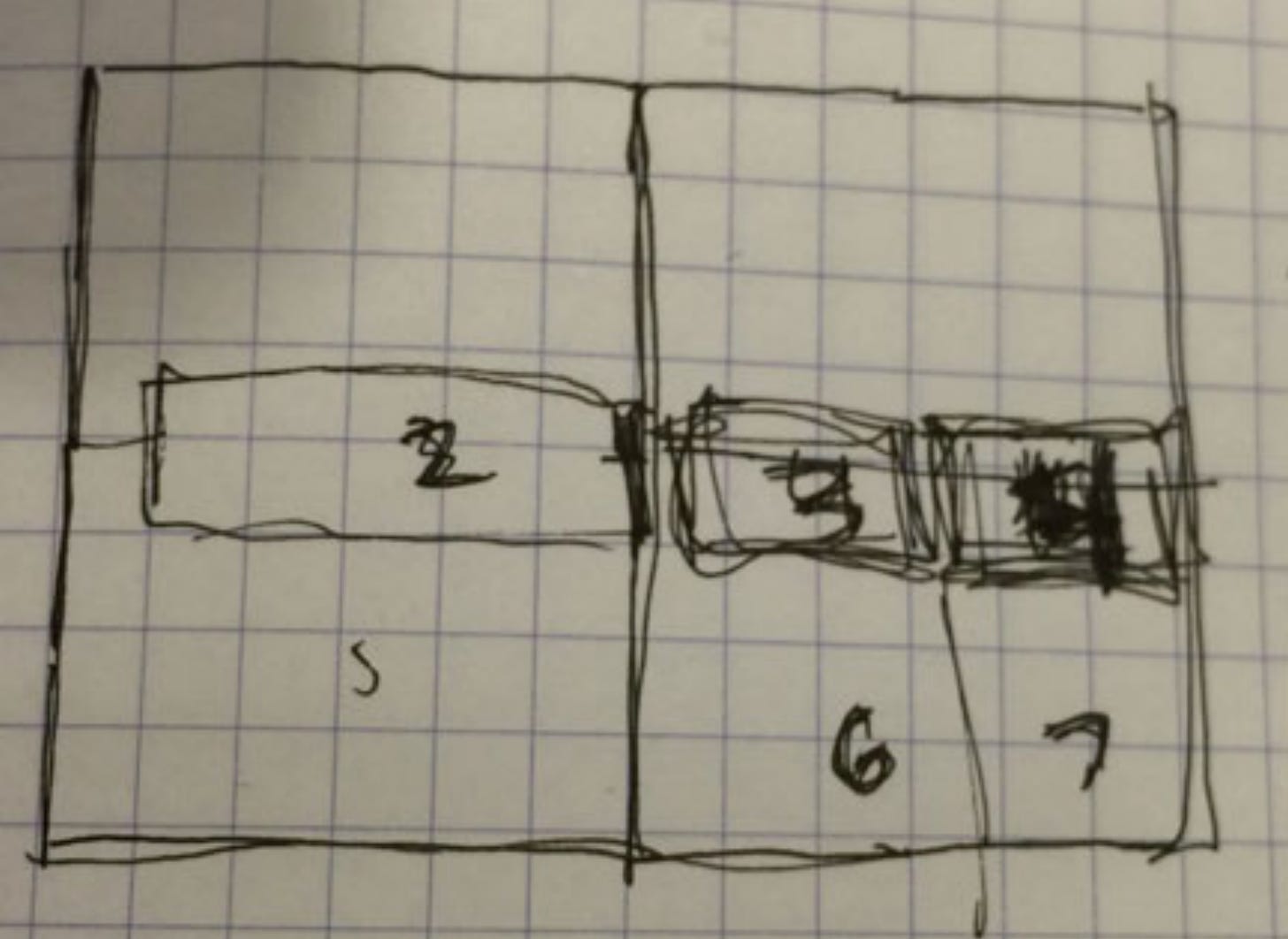

MF: I’ll send you a great example, I think, of both how I wrote for Ward, how I tried to stay out of his way, how I’d try to pace and break the page sometimes explicitly and sometimes not, how I would end up over-loading the thing with ideas, try to draw what I was thinking, then realize what I was doing, feel bad about it, apologize — all in the script! — and then Ward took it all, did something smarter, more clever, more interesting, and better than I ever could’ve hoped - all in two pages with about fifty words. He’s god’s most perfect angel and I love him.

At this point, let’s step away from my conversation with Matt to see what he’s talking about here. I’m going to share with you his “Draft 1” script for ODY-C #7 that he sent to artist Christian Ward to work from. This represents two pages of story. I’m then going to share how Ward executed this page to illustrate Matt’s points here. If any of this isn’t especially interesting or helpful to you, skip ahead to the next line break.

PAGES SIX AND SEVEN

I've attached a phone-shot of how I sketched the page out to organize my thoughts; I'll refer to it explicitly below just so YOU understand but please know that once you get my meaning you can and should do as thou wilt. Don't feel beholden to the below; it only exists here as a roadmap to my own thinking.

The dominant image of the spread takes place WAY BACK WHEN. After the brothers HYRAR and ZHAMAN were born yet before they unified Q'AF. This was a time of civil war, when, we'll learn in the text, that the brothers had been separated for their own safety and to protect them from Zeus' (Or Poseidon's) (Or Herakles's) assassins and as centuries passed, they unlearned their connection to one another. So well hidden were these two tribes, these two worlds, that, inevitably, there came the day when they met as enemies, unaware of their origins.

So anyway: this is a shot of intertribal, interplanetary, warfare. Staggering! Powerful! Tremendous and terrifying! These are two tribes of techno-barbarians (the two BOYS, now YOUNG MEN, lead; everyone else on the field of battle are WOMEN done up BIG BARDA-style, great barbaric titans (titanesses?) with crazy sci-fi armor and weapons, and fur pelts and leathers... a big smashed-together whatthefuck of eras and imagery. HYRAR and ZHAMAN should wear head-to-toe super-armor; they are their peoples' champions and will face one another down to the death here in a bit (or so they think).

The panel indicated as 2 cuts back to Ene and Co. for a minute - we see them sitting around a smoldering plasma well (as though it were a campfire or fireplace) and bonding via that oldest method to bring people together: getting sloppy-ass drunk and telling stories. So it's like a security camera shot of the group, sitting down and guzzling as STARBUCK holds ENE'S rapt attention. There needs to be a window of sorts, a glass wall, SOMETHING past STARBUCK so that we can see the ROYAL TEMPLE in the distance. It comes up later.

PANEL THREE is of YOUNG HYRAR -- a BOY still -- sits on a throne, glaring AT CAMERA like a tiny warlord. He sits surrounded by a cluster of WOMEN-WARRIORS.

PANEL FOUR is a kind of matching opposite of YOUNG ZHAMAN. Same situation -- the only boy among ferocious, killer, women. Maybe if HYRAR sits on a throne, ZHAMAN sits lotus-style. Maybe play up differences of style and discipline between the two tribes.

PANEL FIVE should be of the mini-worlds within the gas giant sphere that form Q'AF as they engage in war with one another, swarms of starships and interplanetary missiles going back and forth from each strangely-shaped polygon world. Look at that: thirty-six words to describe two fucking planets engulfed by another planet trying to kill one another with fleets of ships and weapons. Ten seconds for me to type, ten days for you to draw. Oy.

PANEL SIX finds us on a field of battle directly behind HYRAR as, in the distance, across the roaring battle plane, ZHAMAN sees him.

PANEL SEVEN reverses that, from just behind ZHAMAN, looking towards HYRAR and HIS forces.

Lots of symmetry here, lots of two-sides-of-a-coin stuff, obviously. The captioning will recap the history of Q'AF somewhat up to this point.

Okay, that’s it for Matt’s script. Here’s Christian Ward’s interpretation of it.

I…I mean…fuck…I don’t know where to start here.

Except Ward’s interpretation of Matt’s script couldn’t be further from what I imagined from actually reading Matt’s script.

I’m going to be thinking about all this for a very long time. But for now, back to my conversation with Matt…

MF (cont’d): Carrying that love out of comics into my TV writing, I can see differences in how I write for the screen now versus how I did when I started.

CH: How so?

MF: Like, we get told not to direct from the page, right? Even though everyone does it in their own ways anyway. But I’ve found these kinds of open-hearted leaps of creative faith mean that now I try to not, like, direct cinematography from the page, or art-direct, or set-design from the page, either. Maybe we all do that, too, without realizing, and it might close off intuitive, surprising, and cumulative connections to the work the cinematographers, or art directors, set designers may otherwise bring. Like, these are professionals all, but they’re artists all first and foremost. They’ll have their own reactions and inspiration and vision to what’s on the page – but if the pages overly prescribe the ideas of one person, then in their diligent execution of those ideas, the project may be inadvertently robbed of their full creative force and energy.

“These are professionals all, but they’re artists all first and foremost. They’ll have their own reactions and inspiration and vision to what’s on the page .”

MF (cont’d): It especially changed how I wrote for actors, too. I started seeing moments when I was acting from the page just as much as directing. If nothing else, having been fortunate enough to work with some truly tremendous actors, I found removing those instances from my scripts got me out of their way and let them make some brilliant choice of behavior or delivery or inflection I otherwise would have smothered on the page. It's all little stuff, too, a word here, a line there, of difference, but it feels like the difference has been immeasurable.

CH: Okay, we’ve just talked at length about how Plot Style set you free in many ways as a comic book writer, leading you to trust your collaborators much more, to look forward to the surprise that comes from being part of a team rather than, for lack of better words, the sole visionary. You’ve brought that revelation to how you tackle screenwriting, where you’ve found “open-hearted leaps of creative faith” created a more welcoming space for others to fully express their own artistic abilities in exciting, unexpected ways. Now I’ve got a question that might seem outside the box. It’s about your marriage to Kelly Sue DeConnick, who is also a comic book writer – an exceptional one, I’ll add. Was this creative revelation — this opening of yourself to greater collaboration, to greater partnership — accompanied by anything similar in your home life? Because it sounds like the kind of growth that could feed into a lot of facets of an artist’s life.

MF: Hmm. I think…I think you’d have to ask her, honestly? It came about during one of those terrible stretches of life – parents and grandparents and pets dying, a tax debt we didn’t realize we had until it was concerning in size, we had two young kids…

I remember a lot of good and a lot of bad from those times. That said, I think we’re such good partners because we tend to work very differently, and we have vastly different interests and creative obsessions. So, there’s not a lot of overlap there, so we can serve as one another's first readers or sounding boards and respond without the baggage that comes with well I would do it differently. Despite that, or maybe because of it — and this was pointed out to us by an exec we both adore, so I can’t take credit for it — we share the same ethical core as people and writers, so somehow all our little Legos snap right together.

CH: I’m married to a screenwriter and share a similar relationship with her. It’s fantastic to have a partner who’s your own personal creative development executive, to use Hollywood terms, who pushes you by being so similar in the right ways but, as storytellers, so dissimilar. Speaking of Hollywood, I’m curious where it fits into your overall creative ambitions. You co-created the GODZILLA spin-off, “MONARCH: LEGACY OF MONSTERS”, for Apple – which looks fucking amazing, by the way.

MF: I like telling stories with words and pictures and kind of don’t really know how to do anything else. And I love film and television, so it seemed like a natural extension. I’ll never stop making comics, which means I tend to say no thank you in Hollywood way more than I say yes.

Like, for example, I once was asked to pitch on a Very Big Thing and said no thank you, because I don’t like the Very Big Thing very much - not that I said that to them. But the idea of developing this Very Big Thing I don’t like very much for a year made me want to drink bleach immediately.

CH: [Laughter] I know that feeling very well.

MF: My no thank you so confused the executives that it led to, I swear to god, three more meetings and, finally, developing another Very Big Thing that I did like very much. And it was great, until the fickle finger of fate swept them out of their offices and off to different corporate adventures. Saying no thank you to Very Big Things vexes people in town in a very real way — “Nobody says no to this, what are you doing?!?” — but, like I said. I don’t really do hits. So, I guess it fits into my creative ambitions as long as my creative ambitions fit into it. If that makes sense.

CH: Absolutely. I would say you’re in a generally unique position for screenwriters, in that you already have an incredibly successful career as a writer. You don’t need Hollywood except for the creative possibilities it offers. I’ve always said “Hollywood” — this being the monolithic money-generating beast we assign some sort of intelligence — loves freaks and the word “no”. It wants outsiders that often make no sense, just because it sounds weird. Like, “What if we get this Pulitzer Prize-winning restaurant reviewer to write BATMAN 8. That would be fucking dope!” That’s you, too, because you use words but they don’t know how to make sense of comic book writers. You’re a freak. Meanwhile, you also say no, something else that confuses and excites them. It’s a bit creepy, but I suppose there are worse kinks in the world.

MF: I think there’s something, too, in a culture where hyperbolic compliments are the coin of the realm, and everybody thinks everybody else is brillllllliant and everybody thinks everybody else is geeeeeeeenius and everbody looooooooves everybody else’s work, so that when someone’s like, “Oh, no, I’m the wrong person for this,” the power of that no resonates. Like, “Oh, shit, wait, maybe this is someone that knows something about themselves, about their work.” If nothing else, maybe they just like it when you don’t waste their time.

“It’s really been my whole creative life the last two, two and a half years especially. But I wanted to be present for as much of the experience as I could.”

CH: What can you tell me about the experience of working on “LEGACY OF MONSTERS”? I know it’s taken up a lot of your life, which is just another way of saying you’ve devoted considerable time to it compared to comic books as of late.

MF: Oh... oh, lordy, I don’t know. It’s been almost five years, door-to-door, from the first document I turned in to our premiere on November 17th. And once our room started in 2021, I pretty much shut down every comic thing I had going except ADVENTUREMAN, so it’s really been my whole creative life the last two, two and a half years especially. But I wanted to be present for as much of the experience as I could. I wanted to learn everything I could, from everyone in every department. It’s my first show. There’s always that voice in my head – what if this never happens again? So, I wanted to be there for it.

MF (cont’d): The show is massive. Epic. The amount of people that put in hours to make this thing real staggers me. We went to Japan, Hawaii, up a glacier, into the desert, onto boats, planes, helicopters, jeeps, trucks. I was on-set for like one-hundred of…106 shooting days? Something like that. It was like flood water. It took all the space I could give it.

Like, you know how in Canada, crews don’t have “base camp,” they have “the circus”? It felt like enlisting in the goddamn circus. I loved it, it was the hardest thing I ever did, I don’t know how to explain it, and I’m still not one-hundred percent sure it really happened. My co-creator and co-EP Chris Black assures me it did, so I’m taking his word for it.

CH: Okay, so you also have a new ADVENTUREMAN series coming out in December, which I’ve only just seen announced. As exciting as screenwriting is — and, god, I know it is — can you imagine a year passing when you don’t write a comic book?

MF: I can’t – ever! It’s the best. If anything else, there are no notes. I mean, if it’s a thing I make up with someone else, we’re only doing the book for each other, you know? It’s the most freeing, it’s the most intensely collaborative, and it’s a hell of a lot of fun. And you can’t beat the turnaround, the route from my head to my collaborator’s pen to the bookstores is short and fast. It’s an art form I adore and feel in my bones. Even if no one read them, I’d still be making comics for myself. It keeps my head together.

CH: I fear we’re almost at the end of our conversation, as much fun as I am having. I have to say, the discussion of collaboration, how far-reaching it was, what it really says about how so many things we enjoy are created, was surprising and very satisfying. I’d like to return to your answer to my first question with all our subsequent chat as context now. I asked what was the last piece of art you experienced, regardless of medium, that made you feel like a hack. You cited two, but the first one was a cabinet box created by Clark Kellogg. You revealed you’re a neophyte woodworker yourself – which is a very solitary act of creation, of artistic expression. You, wood, tools, alone. There is no collaboration, I mean, and the outcome is only something you can blame on yourself. I’m curious what you take from this experience, emotionally, spiritually, whatever.

MF: It’s funny, I came to it because I was reading books about craft by people not writers. And I can’t remember the chain that led me to it, but I came across a book on the importance of craft and working by hand called HANDMADE: CREATIVE FOCUS IN THE AGE OF DISTRACTION by a cat named Gary Rogowski. I found it, like Sondheim’s MAKING THE HAT or Hofstadter’s GÖDEL, ESCHER, BACH, or HOW TO READ BUILDINGS by Carol Davidson Cragoe, to be invaluable in defining or refining my own work idiom. Long story short, he runs a woodworking school that used to have in-person classes in Portland, I showed up, and now I’m a guy that has chisels and shit. And there’s something pure and freeing about working on something by hand, by eye, by sound. There’s something pure and freeing in chasing a right angle. If a thing is true and proud, it’s right. If it’s ninety degrees, it’s right. If it’s eighty-nine, it’s wrong. No notes. No feedback. It’s true and proud or it’s not. It’s math made physical and, if you’re lucky, the physical made beautiful, rendered simply and with function. I like making small things well that are of use and serve a function for which they’ve been designed. And when I mess something up, I can fix it. Until I can’t. Then I toss it in the fireplace and it makes a cold room bright and warm for a minute, long enough for me to re-find my way. I’ll sharpen up tomorrow and start over.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world: