Q&A: Writer Ed Brubaker on Making Crime Pay (While Protecting Your Voice in Comic Books and Hollywood) - Part 1 of 2

From real-life crime to crime writing - and, of course, superheroes - the comic book titan turned TV creator discusses his creative journey

When Ed Brubaker’s name showed up in the comments section of this Substack, the art junky in me screamed.

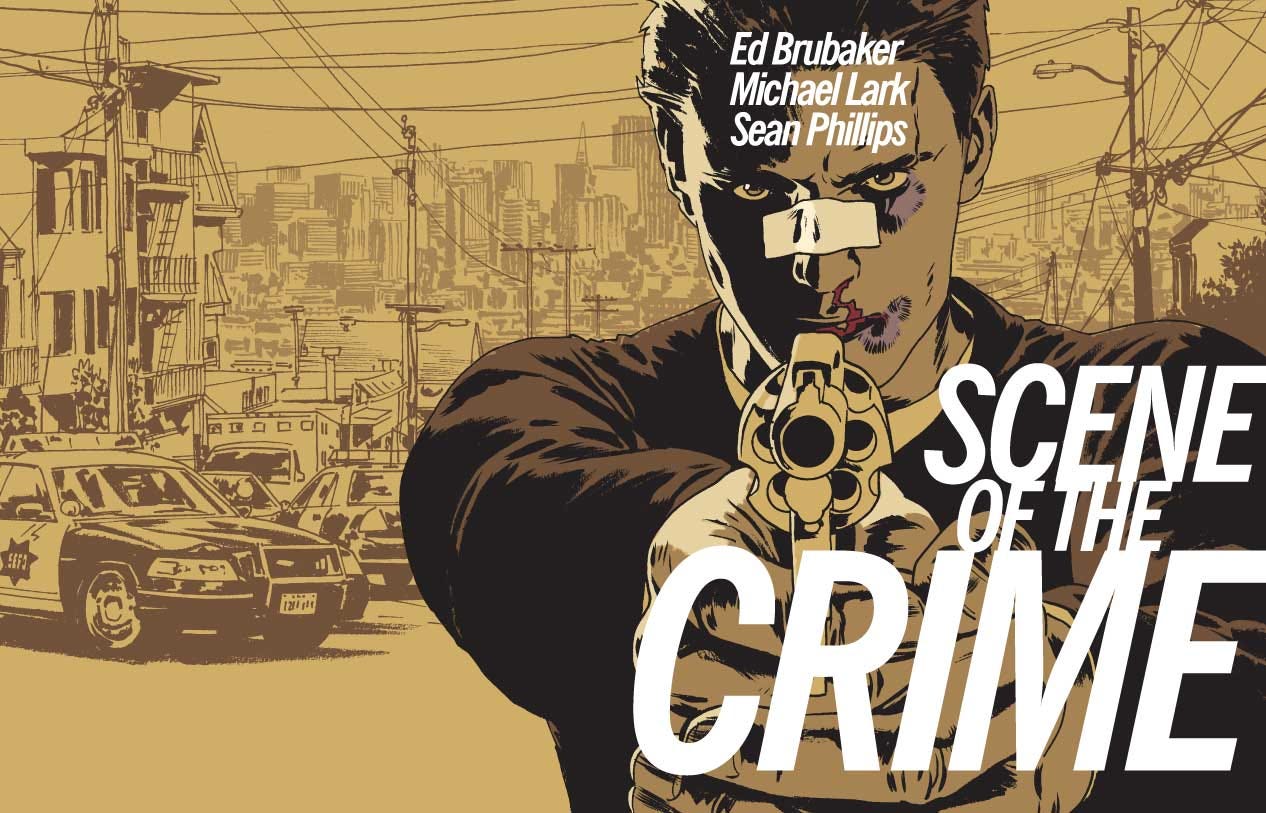

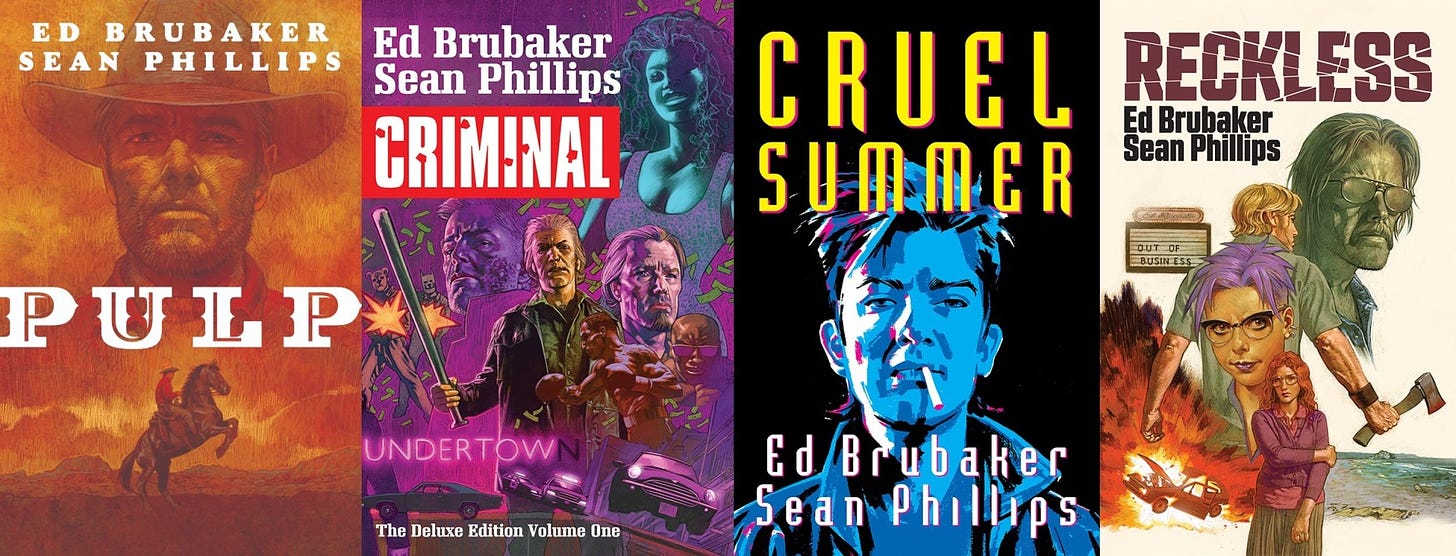

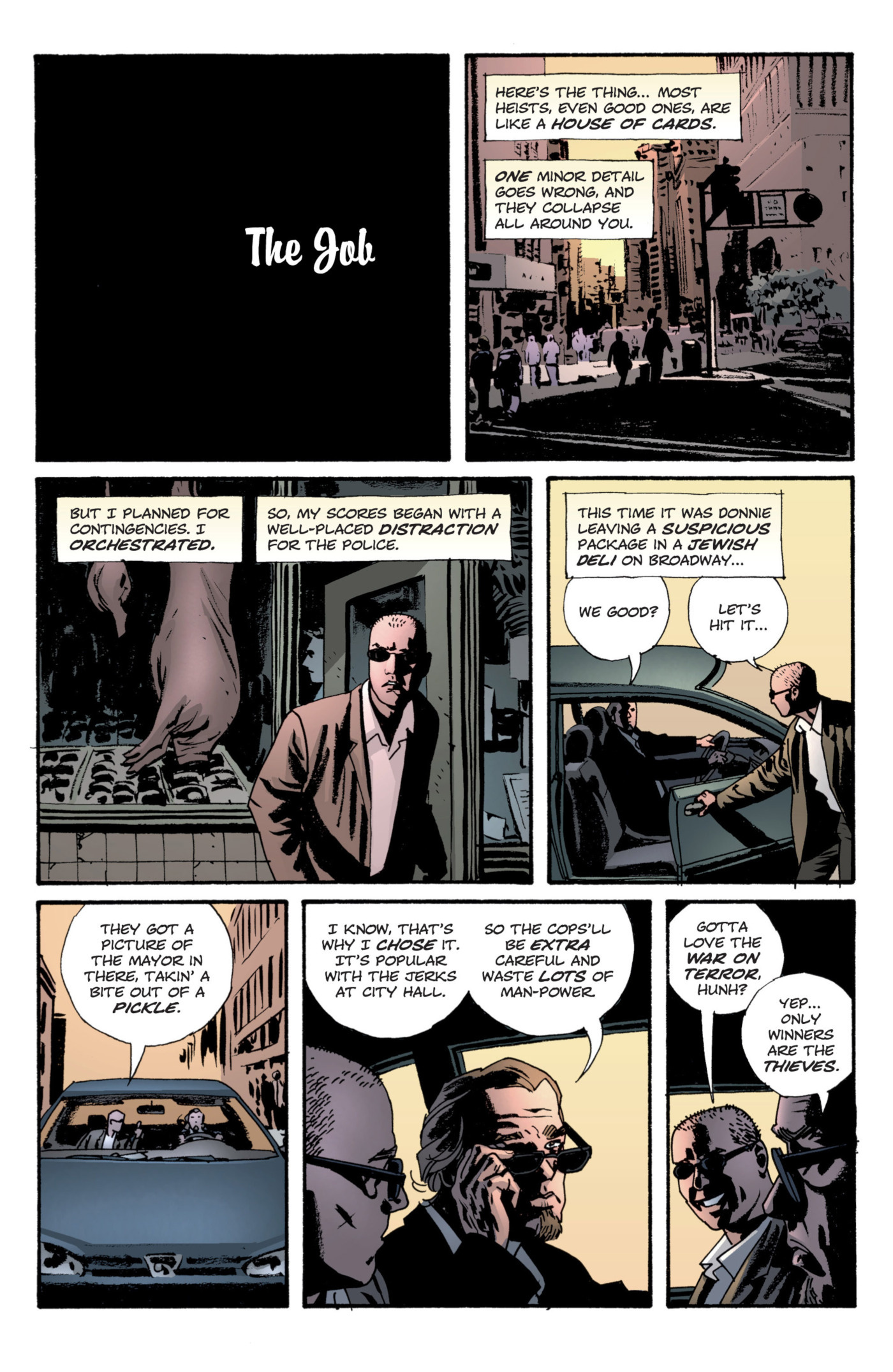

The multi-hyphenate storyteller — who has won more Eisners than I feel like counting — has been a part of my creative life since I first discovered his semi-autographical comic book LOWLIFE (1992) in the nineties, one of those independent titles that end up making you feel like you’ve been let into a secret club. I know I read a couple of his stories in DARK HORSE PRESENTS back then, too, but it wasn’t until SCENE OF THE CRIME (1999) that he became a writer I sought out by name alone. By the aughts, he was the new hot young thing at DC thanks to his exciting work on various Batman titles amongst others. His transition to Marvel led to him famously killing Captain America, resurrecting Bucky Barnes by way of creating the Winter Soldier, and an outstanding run on DAREDEVIL. At the same time, he launched his creator-owned series, CRIMINAL (2006), a gritty, blood-soaked, beautiful contemporary noir that remains one of my favorite twenty-first century crime series in any medium.

Ed writes dark, weird stories that, when it comes to franchise characters, blow up all expectations and all too often become seminal moments in their histories and, when it comes to his own creations, typically dwell on bad people who make a lot of bad decisions. One thing you know for certain whenever you pick up one of his books is you’re about to be surprised, often gobsmacked, as much by what his characters do to swerve the plot this way and that as his dialog and wicked sense of humor. By the way, this is also what makes him such a fit for Hollywood, where he began a side hustle as a screenwriter not long after the turn of the century. The side hustle has since become one half of his creative life, as he now divides his time between writing the comic books that keep him creatively sane and creating and/or running TV series such as “TOO OLD TO DIE YOUNG”, “BATMAN: CAPED CRUSADER”, and an upcoming adaptation of CRIMINAL.

My conversation with Ed shifts across time and mediums and between the personal and the professional, but always returns to one simple struggle: how do you find and protect your voice given all the professional considerations, especially when it comes to Hollywood, that can get in your head?

In Part 1 of our talk, we’ll primarily focus on his journey as a comic book writer and creator. In Part 2 — which will show up in your inboxes tomorrow if you’re a subscriber — we’ll dive into his rocky transition to TV writing and what that journey has taught him (and can teach you). Read, learn, enjoy.

COLE HADDON: Can you remember the first piece of art that made a real impact on you? That today you can trace a line back to?

ED BRUBAKER: Probably the comic strip PEANUTS, which I read most of my life, from before I could even read words. There are some weeks of PEANUTS — from the sixties and seventies — that I still know by heart and think about to this day.

CH: Such as?

EB: Like when Charlie Brown’s head becomes a baseball and he has to wear a bag, or the whole procrastination storyline over Christmas break where he doesn’t read GULLIVER’S TRAVELS until the night before school starts again. But also, just in general, the sense of loneliness and soulfulness and understanding that was in [Charles] Schulz’s work was so simple and real and, I felt, really spoke to me, as a Navy brat moving around the world a lot and feeling a lot of loneliness growing up. I felt like Schulz understood life as I saw it, too, or maybe I see life the way I do because of his work - who can say?

CH: Not the comics reference I expected, to be honest. But it makes a great deal of sense when I think about your work.

EB: Well, I also was really taken with Marvel comics from the first time I saw them, back on the Navy base at the PX in Gitmo, when I was four. I can vividly recall these old splashy covers with the characters fighting and in heroic poses. Spider-Man with Gwen Stacy’s clone’s leg in the foreground as he’s like “No! It can’t be you! You’re dead!” and having no idea what this was, but needing to read it immediately. Iron Fist was just starting then, and I think I read his origin before I read Batman’s, so it stuck with me in a big way, this kid watching his parents die and then becoming a kung fu hero. Luke Cage, Captain America and the Falcon. I was reading a lot of that stuff — and old Archie comics — when I was just four or five years old because the PX had a bunch of stuff from random years, just whatever old shit the Navy could get their hands on.

CH: You described Charlie Brown’s sense of loneliness as something that really spoke to you as a child. I wasn’t a proper military brat myself, but I grew up more or less on an Air Force base and knew all the kids, like you, who had to move around a lot and crash-land in these weird, new communities every couple of years. Were you a lonely kid, then, the one with his face always buried in a comic or glowing from the light of the television?

EB: Yeah, up late at night with a flashlight under the covers. My older brother and I didn’t get along, and that life — living on the base or near it — you don’t have long-term friends the way other kids do. You don’t grow up with the same few friends. You make a friend and they move away six months later, or two weeks later, and that’s just the life. So, comics and then, later, books, were my security blanket, I guess.

“I can’t remember any time I wasn’t trying to make stories of some kind.”

CH: It’s different for all artists - when their “calling” comes. When did you first think becoming a storyteller was, for lack of better words, your destiny?

EB: I can’t remember any time I wasn’t trying to make stories of some kind. I actually wanted to draw comics as a kid, and only started writing so I’d have something to draw, but I think I was always more a writer who drew than a natural artist, which is why I don’t miss drawing comics that much I wasn’t that good at it, so that helps. So, I was always starting comic stories and not finishing them as I grew up. Or finishing them, but they were terrible. That was really one of the few constants in my life until I started actually getting published as a teenager.

CH: Your answer makes me feel less alone in my own journey, except the part where you started getting published as a teenager. I spent all of high school thinking I was going to illustrate comic books for a living. My every waking minute was spent working at it. And it wasn’t until I was about eighteen that I figured out that, while I could get there, I could do something generally interesting on the page, it took me five, six times as long as it should’ve – and, most importantly, I didn’t enjoy any of it. The written word was where it was really at for me, even if everything I was writing at the time was some spectacularly derivative shit.

EB: Yeah, for me I can recall a moment where I wanted to write stories that I didn’t have the ability to draw, and that’s when writing stories for other people didn’t feel like my side-job, but the thing I was actually meant to do.

CH: So, how did you go from a superhero kid to a crime writer as an adult?

EB: I guess it started when I was in high school, in the early eighties. I got into punk and started reading a lot of different books and comics, undergrounds and alternative comics. LOVE AND ROCKETS, WEIRDO, stuff like that. And Black Lizard Press was starting out then, reprinting these old cool pulp paperbacks, and I’d go to noir fests, and stuff like that. So, I think I was starting on a path towards becoming a crime writer then, without knowing it. Around that same time, this cop murdered a girl in my town and almost got away with it.

CH: Christ.

EB: Yeah, it’s super fucked-up. Anyway, I followed that case really closely, and a few years later, when I lived in Berkeley, there was a really fucked up murder in the woods not far from my apartment - and when I first started writing crime comics, those murders were things that I drew from, these cases I’d been a bit obsessed with. I think that was when I started to realize writing fiction would be my job, and that crime fiction was where my voice was.

“I think I was starting on a path towards becoming a crime writer then, without knowing it. Around that same time, this cop murdered a girl in my town and almost got away with it.”

CH: It’s interesting that you can pinpoint, to some degree, where your “voice” originated.

EB: Of course, I was also a drug addict and criminal for a few years as a teenager, so that is a big part of why I am drawn to crime stories, too, because I lived some of it.

CH: I’m going to come back to your addiction in a moment. First, can I ask what about these murders fascinated you so much? What about your understanding of the world, where you were in your life, your home life, school — whatever — drew you to them?

EB: The proximity at first, I suppose. And the tragedy of them. The details being so weird in both of them. The cop in the first murder was actually on the news giving other women advice about how not to get attacked on their way home from work, like a police ride-along a few days after the murder, by pure chance, which is how he was caught. All these other women called the cops saying “Hey, that cop on the news pulled me off the highway at the same place that girl was murdered and was super creepy.”

The second one, her boyfriend confessed and said he went back to have sex with her dead body, but a lot of people think the confession was coerced, so I have no idea. But it happened in a place I used to go, and it was incredibly tragic and the whole town was affected for a while, it felt like. In a pre-“SERIAL” world, it was rare to encounter stories like that in your actual life. Like when the Night Stalker was running around and you were scared of your landlord walking across the yard at night. I remember stuff like that.

CH: In those early years of your career, what role did your art — your writing — play in your mental health, working through your demons, recovery? Were you even in recovery at that point or was something like LOWLIFE written and illustrated while still wrestling with addiction?

EB: Oh, no, I’d given up drugs by the time I was nineteen or twenty, for the most part. But I was drinking way too much for most of my twenties, probably to self-medicate depression and anxiety.

EB (cont’d): It’s hard to say how much I was aware of considering writing like therapy back in the early days, but you know, now it’s clearly that. To the point that when I’m not writing a story, I feel like something is wrong with me. But I’ve always drawn from my life and my own failings and heartbreaks and bad decisions to tell stories. The hardest part of writing for me, with each story, is figuring out what feels the most urgent to get out of me onto the page. I’m always going for a feeling or a memory, something that makes me feel something and isn’t just moving characters around on a board.

CH: “When I’m not writing a story, I feel like something is wrong with me.” I really feel that. When I was much younger, I paid my way at University of Michigan in part with a grant I was given for a draft of a book I now understand was filled with a lot of lovely sentences and sentiments and ambitions, but generally terrible. There was one very autobiographical line in it, though, that’s always stuck with me: “I’m like a shark like that; swim or die, write or die.” It even impairs my ability to enjoy things such a vacations because I’m standing in some magnificent castle in Hungary and, instead of really being there, I’m thinking about how something about the moment, whether a historical detail or even just something I’m feeling, can manifest in my work.

“The hardest part of writing for me, with each story, is figuring out what feels the most urgent to get out of me onto the page. I’m always going for a feeling or a memory, something that makes me feel something and isn’t just moving characters around on a board.”

EB: Yeah, that’s kind of part of being a writer. The people in your life have to either accept or put up with the fact that you’re always partly somewhere else in your head, working on some idea or thought. Maybe it’s just how writers, in particular, interact with the world - through making and telling stories. It’s such a huge part of cultural history, storytellers around the fire talking to the cave folks and tree people, right? Maybe storytellers have always been apart from the rest of society a bit, I wonder, in some ways.

CH: I think you’re right. Storytellers are truth-tellers. The good ones at least, the ones who understand the historical assignment, are there to figure out something about themselves and, by turn, help their community understand itself better. Maybe that sense of being apart, that disconnect that can break many of us, also lends itself to whatever objectivity we hopefully express.

EB: Yeah, I think if you’re doing it right, you’re able to look at the world from a lot of different perspectives and bring empathy and understanding even to the kind of people you might hate, or the people ruining the world.

CH: So, by the time you made the leap to DC, how would you have described the voice you had developed as a storyteller? What made a story an “Ed Brubaker story” in your mind?

EB: By the time I started writing for DC, I’d been publishing comics for about ten years, so I’d written a lot of first-person short stories and a few crime comics – one drawn by Eric Shanower and one by Jason Lutes. But, like, when I was doing SCENE OF THE CRIME at Vertigo, I’m pretty sure I was just trying to be the Gen X Ross Macdonald or something. I knew I liked writing crime stories that felt very human, but when I look back at those early years, I see a writer trying too hard.

CH: I’d like to hear more about that.

EB: I’m not sure how to describe it, really. I always leaned more towards a conversational style of writing, jumping around, and going on tangents like a conversation will, but so much of writing is gut instinct that when you say “an Ed Brubaker story”, I’m not sure what that means other than a story I tried hard to make not suck. Like, you want to entertain yourself, right, as much as you can at least, and you want to make something that you think people will like and get something out of when they read it, feel something human resonate inside them…but really, when you’re writing, you’re just in the moment and you’re calling bullshit on yourself over and over again on every idea you come up with. Until you get one that feels right, that doesn’t bump you. That’s all you can really do, just listen to the words and see if they feel right.

“When you’re writing, you’re just in the moment and you’re calling bullshit on yourself over and over again on every idea you come up with.”

CH: This is something I don’t hear enough writers talk about. Their personal bullshit radar for what’s interesting to both them and their readers – but also true. Some of us seem to develop this tool more naturally, others must work diligently at it. Then all these things get in the way, too, clouding, obfuscating our radar’s efficacy – most often, the need to pay bills, I think. Short-term gains, such as satisfying an editor or a producer, can have long-term consequences on how you see your own work and, of course, how others see it.

EB: Oh yeah, totally. I actually would advise thinking as little as possible about who’s going to read a story when you’re writing it, whether it’s prose, comics, screenwriting. Don’t let that get in your head.

CH: I’m going to have to ask more about this, but please continue.

EB: Make a thing that means something to you first, and hopefully your gut instinct will also make it feel exciting and entertaining and maybe even moving, to other people, too. But aiming at moving targets is a fool’s errand, and that’s a lot of what Hollywood screenwriting is, really. I often think the Smiths song “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now” should be the WGA anthem – “I was looking for a job and then I found a job and heaven knows I’m miserable now.”

CH: It really is a perfect lyric for us.

EB: Because aside from the executives or producers who are fun to work with and understand your writing and want to help you make it better — they do exist and we screenwriters love them—

CH: Yes, yes we do.

EB: —much of that job is just a bunch of people asking for you to make something different, not better, not more true to the thing you’re trying to make.

And I’m sure they think they’re trying to make it better and more commercial, but what the reality is, fairly quickly you begin to feel like you’re a jukebox or that you’re taking dictation, and that will fuck your writing brain up completely. Just as a studio over-noting a director or actor will fuck their head sideways, too.

EB (cont’d): Taking it back to the question though, why I say try to never second-guess the readers is that several times I’ve finished a book and thought, “Oh god, I like this, but will our readers?” and so far those have all turned out to be the biggest hits me and Sean Phillips — my artistic partner — have done. So, you just have to follow your gut and hope for the best, knowing you can’t control how anyone reacts to your writing, you can just try your best.

CH: I have to finish up this exchange before I move on to the rest of the interview now. To clarify, I never think about the reader when conceiving a story or, for the most part, while writing it. But I do periodically check in with this audience because I think what I’m doing is having a conversation – a dialog– with them as much as it is the rest of art history that inevitably is feeding it in some way. Dialog is the key word here. I find there’s a bit of divergence amongst artists about whether the audience matters to the artistic process, and it sounds like you’re adamant they should not be part of it at all? I don’t specifically mean second-guessing readers, mind you. I mean how your audience will experience your work, how they’ll internalize it – is that something you give no thought to in your process?

“When I’m writing, I’m serving the story and the characters and what feels right. I’m hoping the readers will like it, but that’s the best I can do.”

EB: No, I wouldn’t say that, exactly. Sean and I have spent over twenty years building a readership, and I can’t be thankful enough for that. So, I never want to let that audience down, but I also would like to surprise them, and on top of that, I need to write something that matters to me as I write it. So, when I’m writing, I’m serving the story and the characters and what feels right. I’m hoping the readers will like it, but that’s the best I can do. So, I have them in mind, but I keep myself focused on what I can control.

And when I say not to worry about who’s going to read it, I mean not just your wider audience, but your mom and dad, your friends, your loved ones. Like, imagine writing a fucked-up story and holding back because you’re like “I don’t want my mom to see something this dark come out of my head.” Write as fearlessly as you can, I guess, is the larger point.

I think my view is more about the process. When you’re writing, you should be listening to your gut instinct and to your characters, those are the voices in your head. Pay attention to those. But that’s just me. Some writers actually poll readers online about what they should write next and if that works for them, okay. To me, that seems insane.

CH: Because it is insane. I’m curious how your voice eventually acclimated to the world of superheroes.

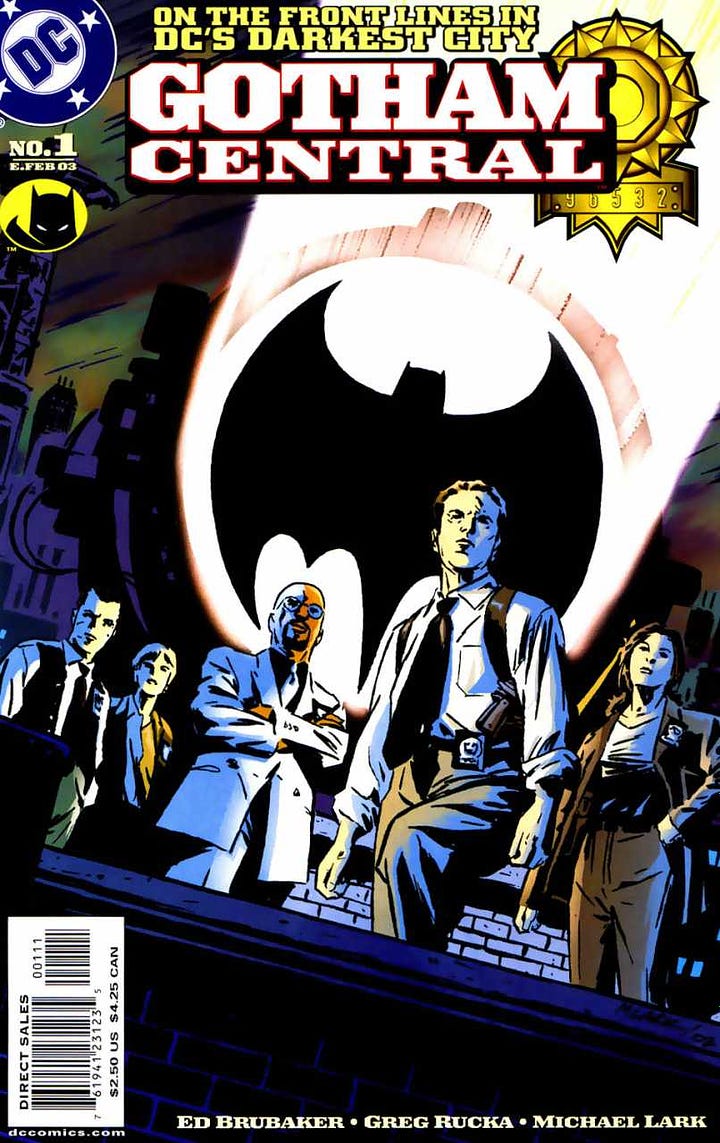

EB: I think for taking what I do into superheroes, what I found was that I worked best with the ones that I could ground in reality and then just heighten it. My Batman years — BATMAN, GOTHAM CENTRAL, CATWOMAN — were very much crime stories but with costumed heroes in them, or villains at least, in GOTHAM CENTRAL. But, it was all about bringing some sense of reality to the material because that’s what appealed to me - and Greg Rucka, of course.

CH: It’s interesting looking back because I can’t imagine many superhero worlds that would serve as a better gateway drug, so to say, to the world of costumed heroes than Batman’s. He’s at his best in ongoing series, I think, when he’s treated like the protagonist of a crime story. Same goes for the world, which is why I enjoyed GOTHAM CENTRAL so much. Was it different with your Marvel books?

EB: With my Marvel work, CAPTAIN AMERICA and WINTER SOLDIER, that stuff was taking it seriously but in a James Bond meets John LeCarré meets Jack Kirby kind of way. I thought of Cap as an espionage soap opera, and I had the time of my life working on it, and those books were a big influence on the Marvel movies – just like [Brian Michael] Bendis and [Mark] Millar’s books were. DAREDEVIL, of course, was just the most noir book you could write, so that was like a gift to write. And hell, I got Bendis to leave him in prison so I could start out at his lowest point. For a while, it was like we were really making magic over there.

EB (cont’d): But one thing that I think made that all work for me, at both publishers, was I had editors that trusted me and didn’t force me to do anything I didn’t want to do. I got ownership of the books while I wrote them, and I put as much into them as I did into CRIMINAL or SLEEPER at the same time. They feel different because they’re superheroes, but the character work in them, I’d say still feels like my work. Lots of tragedy and guilt, lots of violence. That’s my wheelhouse.

CH: You just said it was like making real magic over there at Marvel “for a while”. Did something change at Marvel or with you? I ask because it wasn’t long after you left Marvel that you joined the writer's room of “WESTWORLD”, but this departure also signifies your last published work on a superhero comic book.

“By the time I quit, I’d written something like eight hundred superhero comics, and let me tell you how almost all superhero stories' third act goes – the heroes are on their back foot, the villain is going to win, but then everyone puts on costumes and goes and punches each other or blasts energy rays from their hands or eyes, and the good guys win. How many times can a human being write that?”

EB: Yeah, I mean, it was just burnout, really. The first five years, before the Disney purchase, it was fun. We’d have big meetings a few times a year and map out the future of the line for a week, and while it was a hard job with lots of tight deadlines, there was — at least for me — a lot of freedom. I was doing books that were selling well and had consistent artists, people liked what we were doing, the movies started adapting them. But at some point it became about every quarter making more profit than the previous one and, as a creator in that grind, it was no fun. They wanted big books to go from twelve issues a year to eighteen, so I was always writing two issues of a book at the same time, for different artists - sometimes not even knowing who. Before finishing one story, I was starting the next, and, honestly, it just broke me.

CH: It sounds like the worst kind of nightmare for me.

EB: It was rough. And you know, by the time I quit, I’d written something like eight hundred superhero comics, and let me tell you how almost all superhero stories' third act goes – the heroes are on their back foot, the villain is going to win, but then everyone puts on costumes and goes and punches each other or blasts energy rays from their hands or eyes, and the good guys win.

How many times can a human being write that? That’s why books like CATWOMAN, or GOTHAM CENTRAL, or DAREDEVIL, or even CAPTAIN AMERICA when I did it were great to work on, because I could write tragedies instead. I mean fuck, I wrote Cap for a year with no one in a Cap costume because he’d been killed and they let me do that.

CH: Still boggles my mind you got away with it, really.

EB: Yeah, for a long time at Marvel I had fun and felt really invested in the work, but eventually it wasn’t that anymore, and I was on team books and not having any fun and I just lost whatever joy was left in it, so I stopped.

CH: You just described how third acts end in almost all superhero books, but you could’ve been talking about superhero films, too, right? I love so many of them, don’t get me wrong. I’m still apoplectic that AVENGERS: ENDGAME wasn’t nominated for Best Picture. But there’s a lot of talk these days about superhero fatigue at the movies — I’m certainly feeling it — and I can’t help but wonder if you would draw any parallel between the audience’s experience of that and your own fatigue after more than a decade, decade and a half really, of telling so many stories inside that specific box?

EB: Oh yeah. I mean, like any genre, there’s good movies and bad movies. I’m not the target audience for most of that stuff. But the best ones, I do really enjoy. And if you’d told ten-year-old me that the future of Hollywood was non-stop superhero movies I’d have thought you were crazy. But this is just a phase, I think. Like, when Hollywood mostly made westerns for twenty years. I’d be more than happy with them putting out eighty percent less of that stuff and trying other movies that are cheaper.

CH: Agreed.

EB: But I don’t look down on the audience that loves superhero movies because I know first-hand you can love Spider-Man and also love Hitchcock and Cassavetes and Scorsese and appreciate them all at the same time. Me loving “ROCKY AND BULLWINKLE” doesn’t prevent me from loving UNFORGIVEN.

But what I see with the superhero craze is kind of a repeat of what they’ve done in comics, cultivated a huge audience and then over-saturating them until they get sick of what you’re selling - because big corps can’t think further ahead than the next three months now. So, they take something that’s working and instead of nurturing it, they ramp it up and bleed it dry, and they kill the golden goose. It’s the new American way, it seems.

Part 2 of my conversation with Ed Brubaker will arrive in your inbox tomorrow if you subscribe to 5AM StoryTalk. We’ll be discussing his screenwriting career in Hollywood, amongst other writerly things, next.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

Love Brubaker's Cap and Daredevil run. As a working writer in comics for 20 years, it's cool to see how many crossover subjects you've brought to your substack. Bonus: 23 min read!!! For $5 a month. Wow! It's commendable how much care and detail you put into your articles. Great work!

I didn’t know it back when I upgraded, but this right here is exactly why I’m paying for your newsletter. Smart, interesting conversations with smart, interesting people. And call me crazy, but I still think your ‘Endgame for the Oscar’ campaign might just pay off.