Q&A: Christian Ward Discusses His New 'Neon Noir' Series BATMAN: CITY OF MADNESS - the Fulfillment of a Lifelong Dream

The Eisner-winning artist discusses his journey as a storyteller and his uniquely 'cosmic' art style

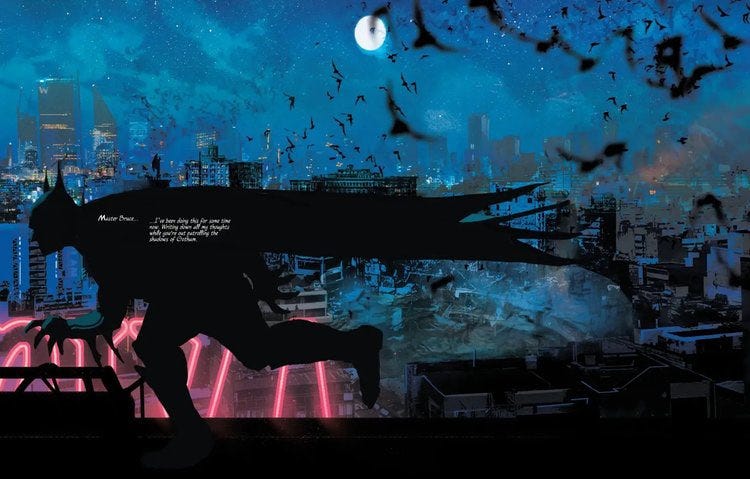

Christian Ward’s art is a neon-drenched trip into the surreal, in which the physical world exists as part of an overlapping multiverse of emotional subjectivity, cosmic fantasy, and delirium that pushes and pulls at each other like gravity. This “magic something” that, in his words, “transports you to somewhere new”, has led to some of the most mind-bending and unforgettable comic book art of the past decade.

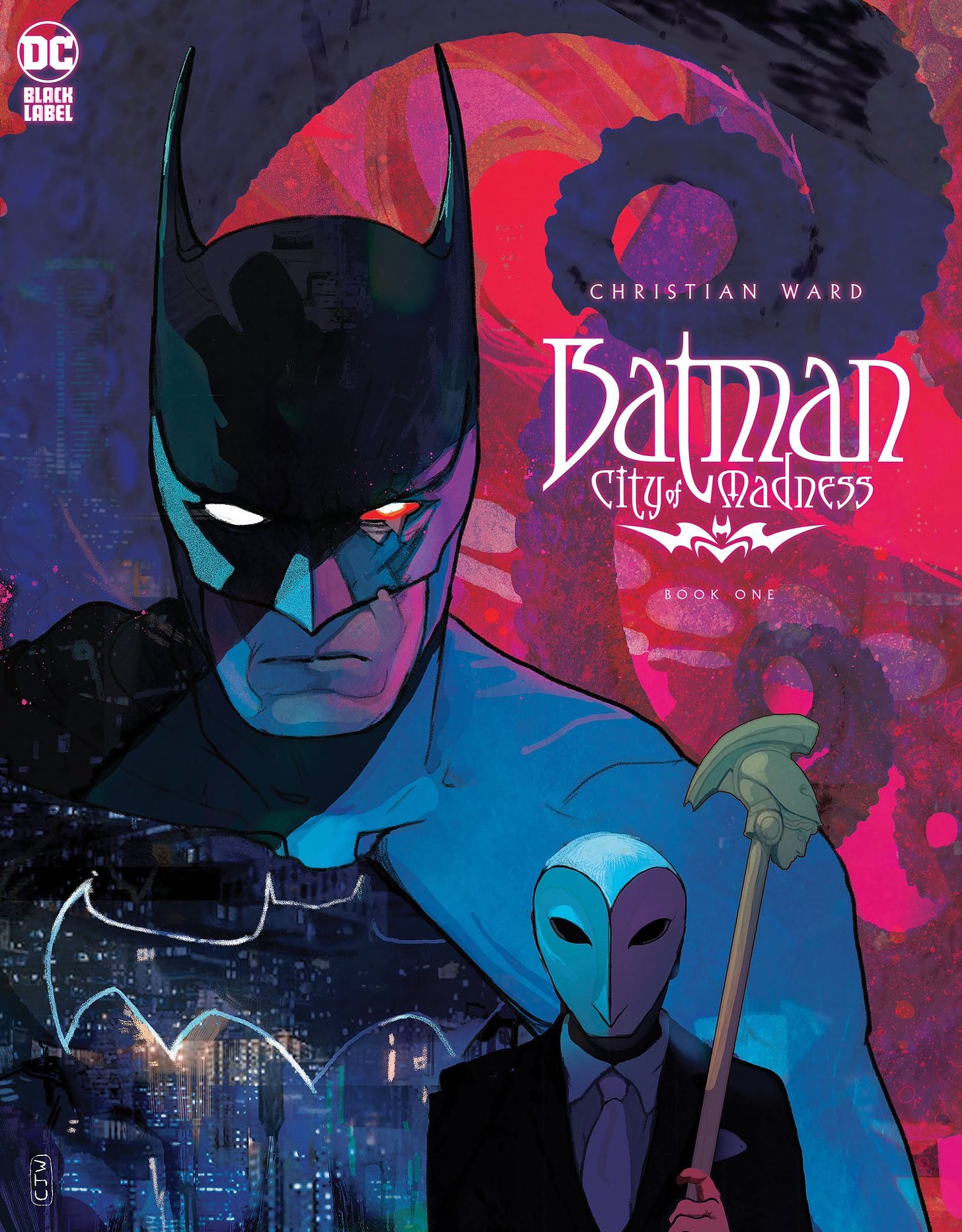

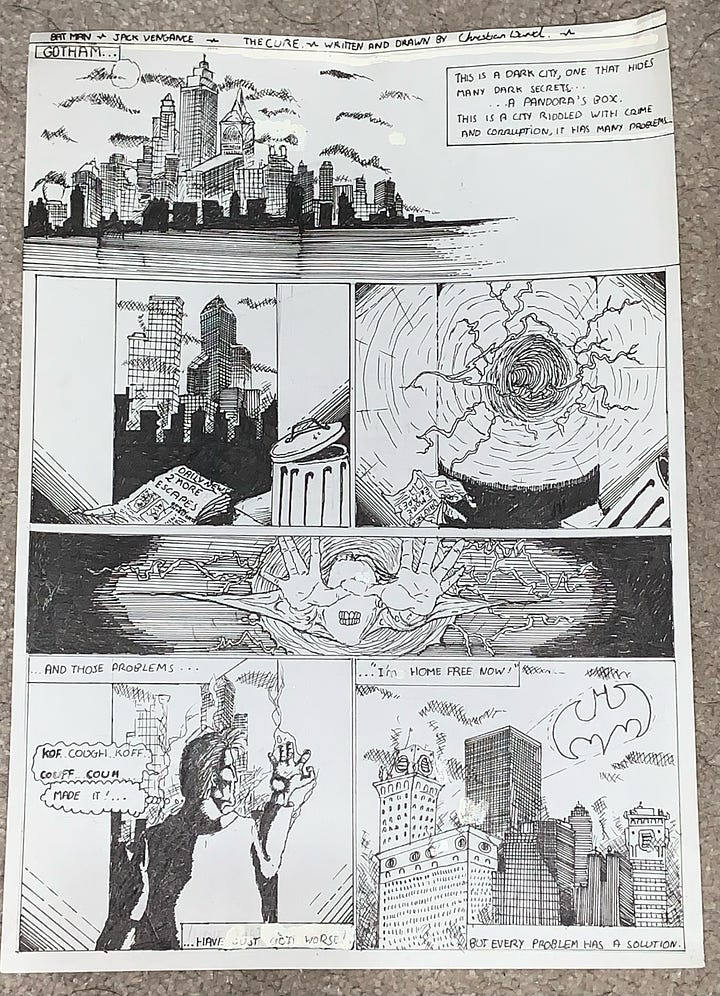

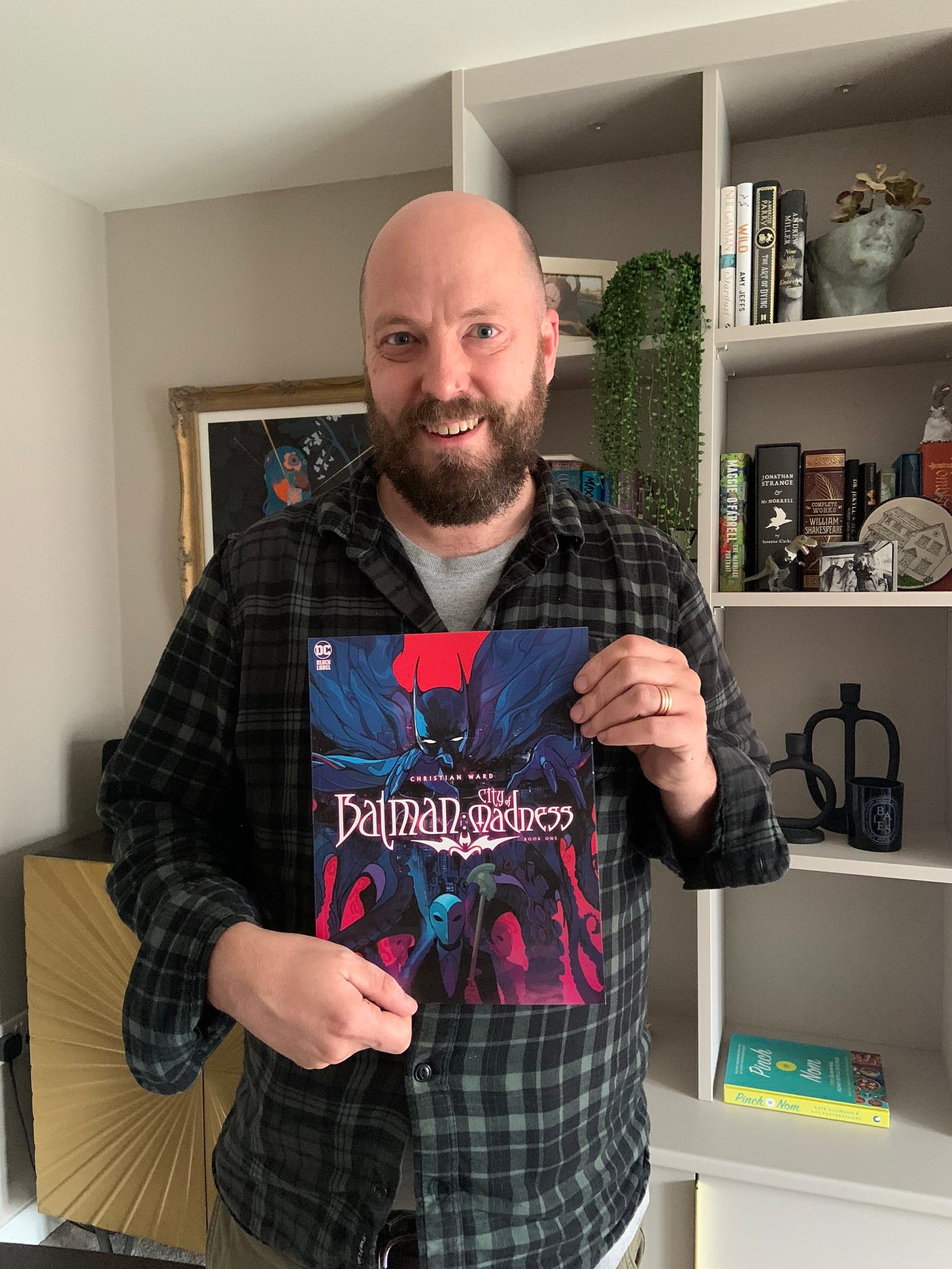

This month, all that brilliant visual innovation — which has earned him multiple Eisner awards — culminates in the fulfillment of a lifelong dream…writing and illustrating a Batman book. Specifically, an unofficial sequel to Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s ARKHAM ASYLUM: A SERIOUS HOUSE ON SERIOUS EARTH (1989), a graphic novel that changed his life as a teenager by opening his mind up to the art form’s expansive possibilities. Christian’s series is entitled BATMAN: CITY OF MADNESS, and is being released by DC’s Black Label over the next three months. I’ll share a description of it below, but after reading it and glimpsing some of Christian’s gasp-inducing art for it, I knew I wanted to ask him to join me for one of my artist-on-artist conversations. He graciously agreed and let me peer into his imagination a bit for what ultimately turned into a quite profound chat about passion and love in art.

BATMAN: CITY OF MADNESS

Buried deep beneath Gotham City there exists another Gotham. This Gotham Below is a living nightmare, populated by twisted mirrors of our Gotham's denizens, fueled by the fear and hatred flowing down from above. For decades, the doorway between the cities has been sealed and heavily guarded by the Court of Owls. But now the door swings wide, and the twisted version of the Dark Knight has escaped…to trap and train a Robin of his own. Batman must form an uneasy alliance with the Court and its deadly allies to stop him—and to hold back the wave of twisted super-villains, nightmarish versions of his own nemeses, each one worse than the last, that's spilling into his streets!

COLE HADDON: Some visual artists come with soundtracks, and I think you’re the epitome of that. It’s impossible to look at your illustrations and not hear Brian Eno or M83, New Order, Clint Mansell and Vangelis and John Murphy for sure, the Aliens, maybe even Sparks. David Bowie, obviously. I wonder, does music play a role in your creative process?

CHRISTIAN WARD: First off, what a flattering selection of musicians and artists. I’ve certainly created some work listening to some of those. I wouldn’t say that when I’m creating art, I’m influenced by whatever I’m currently listening to. In fact, I’m as likely to create cosmic space-scapes while watching “ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT” as listening to the score from PROMETHEUS, but I think you draw comparisons between me and the artists you mentioned because we all enjoy as sense of narrative along with that “magic something” that transports you somewhere new.

CH: For me, I think it’s a combination of that narrative and what I hesitate to call the supernatural. Maybe metaphysical is the right word for it. Your work is defined — again, at least for me — by a kind of multilayered texture that seems to suggest an existence that spans realms of consciousness and existence. The physical, the psychic, and the cosmic worlds.

“The idea of reality excites me, or rather the idea of what it could be.”

CW: The idea of reality excites me, or rather the idea of what it could be. And I think you hit the nail on the head with the word multilayer. Life exists as a series of layers, doesn’t it? You have the superficial, dare I say, the beautifully mundane day to day of it. Eat, work, rest, sleep, repeat. Even more so with young children. Feed the kids, tidy up after the kids, on and on. Then, the next layer is the love - when you stop to realize how much you love the life, the kids, your partner, your friends and family. But then you go deeper, and it’s the, “Why am I alive? How did we get here?” And deeper still, “What else is there? What is beyond what we know?” I think good narratives or good art works in the same way. Superficially, it works. You love looking at it or experiencing it. It’s entertaining. But you can go deeper and start to have a discussion about whatever the work is about.

CH: Let’s step back and talk about your secret origins, so to speak. Can you pinpoint in your memory what the first piece of art was, regardless of the medium, that really made its mark on you, that shook you, that maybe even made you think, “Well, hell, I want to do that?”

CW: For me, it was the comic books my father would buy me. Disparate copies of X-Men, Spider-Man, Hulk, and — the favorite — Batman. Interestingly, though, it was as much the story that inspired as the art.

CH: How so?

CW: These glimpses into another world, because of the random issues I never quite knew what was happening, were so exciting. From a young age, I’d make up stories and even put on shows for family and friends, using the back of a couch or my bed as a stage. The art was always a conduit for entertainment, storytelling, and taking people places. It’s why, also, I was transfixed by film and then by novels as I was by comics.

“The art was always a conduit for entertainment, storytelling, and taking people places.”

CH: Did you imagine a life working in either of those mediums instead?

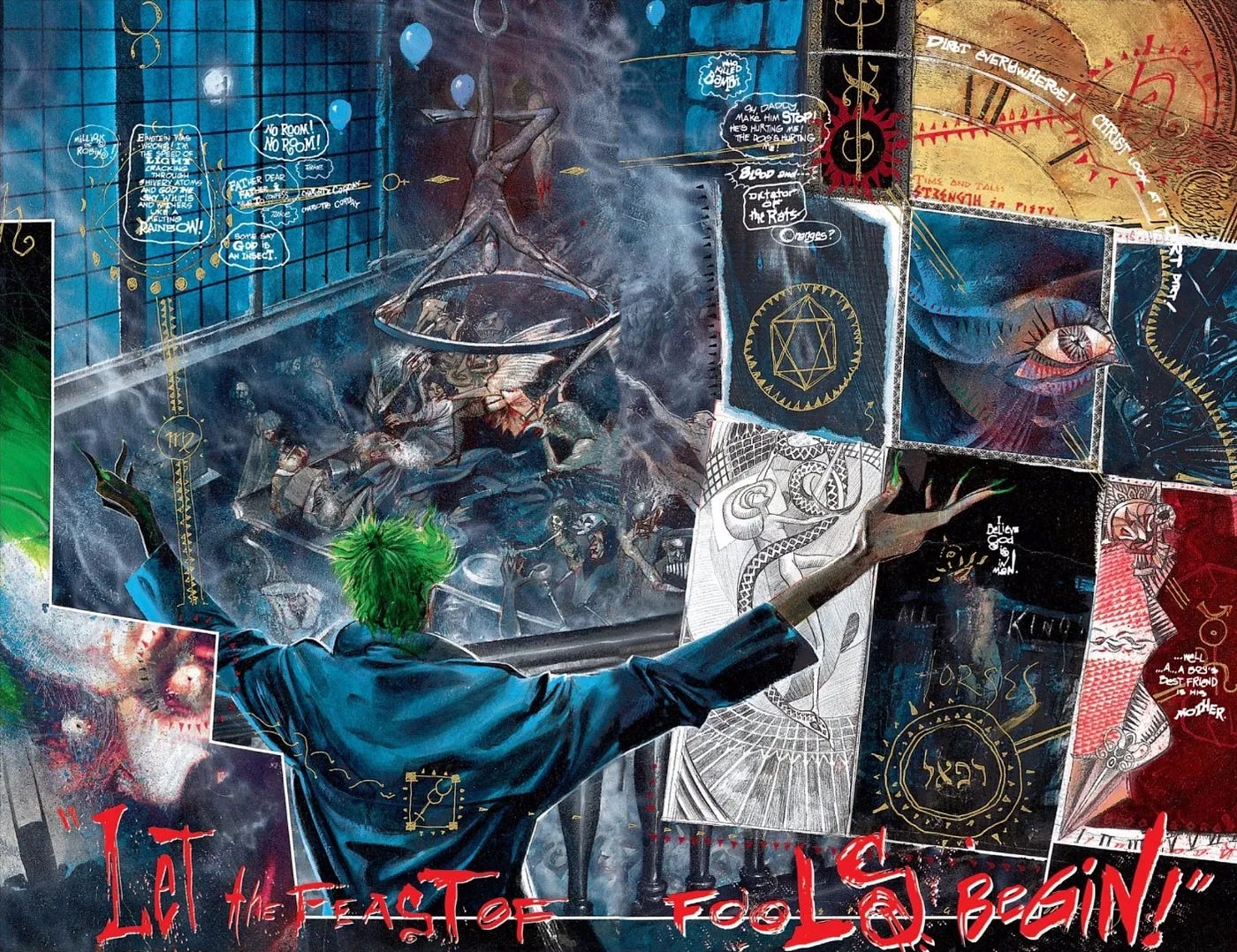

CW: For a spell, despite not having the maturity to understand the mammoth process of moviemaking, I wanted to make films. It wasn’t until my thirteen Christmas that I was given a copy of ARKHAM ASYLUM: A SERIOUS HOUSE ON A SERIOUS EARTH that my mind was blown wide by what you could do with comics. Through my teens and early twenties, a drawer full of half-started novel manuscripts and short stories that seemed to point me toward prose, that book planted the seed that became my comic career.

CH: What about ARKHAM ASYLUM resonated so much with your thirteen-year-old brain?

CW: On a base and very simple level - it was painted. I was so used to comics being pen and ink. The sheer lushness of Dave McKean’s art was transformative. Paint. Collage. Photography. It created — and again with this word — layers of reality I’d never experienced in comics before.

CH: Tell me, can you trace your path from your teenage experiments with storytelling to illustrating comic books?

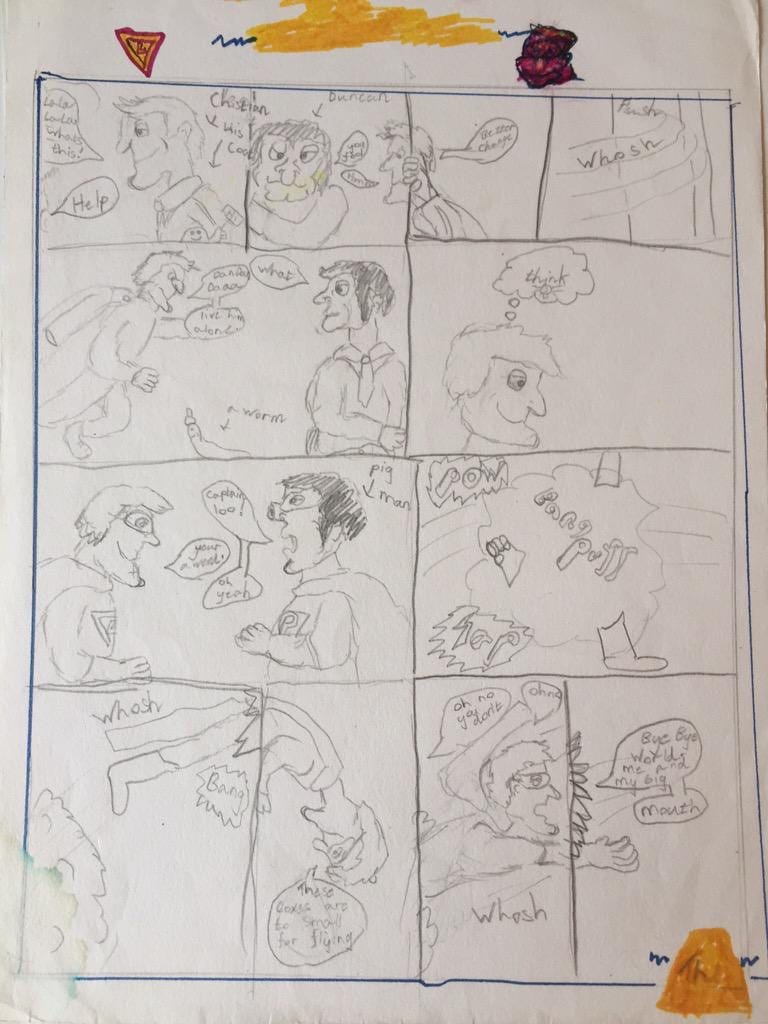

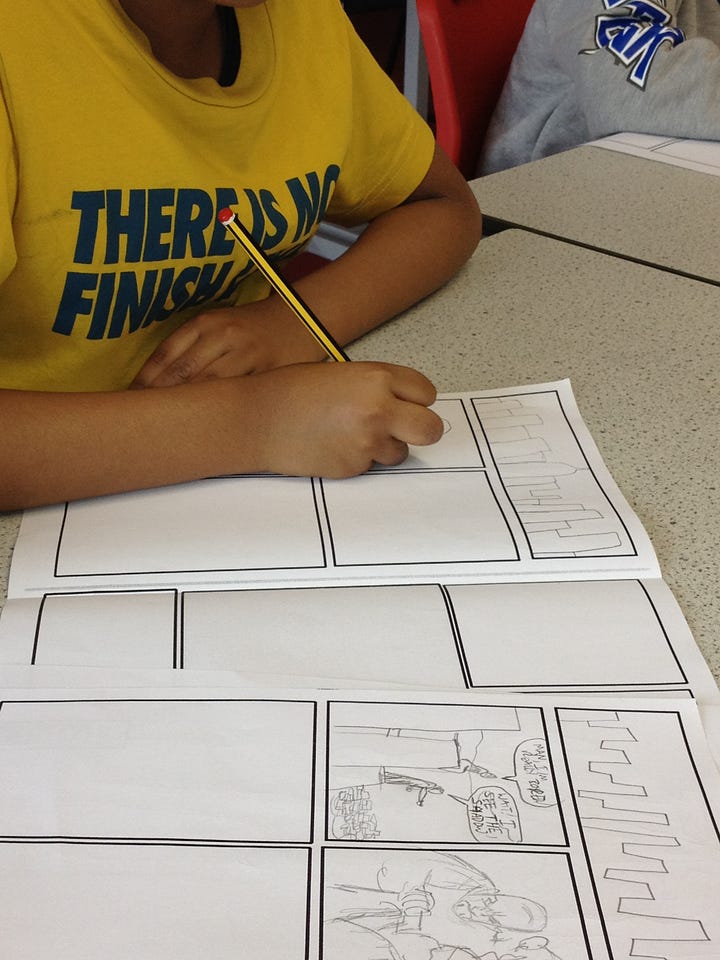

CW: When I was around ten years old, I would create one-page comic strips that I’d photocopy and sell on the playground. I was the hero, my friends my sidekicks and the school bullies and teachers were the villains. It was the first time learning how to sell your stories.

CW (cont’d): In my teens, my art teacher would begin what became my weaning off comics. I began to see comics as an unrealistic career. “You can’t do that as a real job” - so I shifted to focus on illustration. That was a real job, right? Post a degree, I was now living in London, far more a fine artist than anything else and very, very poor. I still remember having to contemplate for weeks if I could afford to treat myself to a DVD or a CD album. A rare occurrence. Comics, too, were too expensive so my first love became forgotten.

“I was using comics in my teaching. Hiding the learning in the fun. One day, one particularly vocal student who was annoyed at yet another comic-laden worksheet, called out loud, ‘If you’re so good a comics, why don’t you do comics?’”

CH: I remember that period in my own life all too well. It’s…not easy. How did you find your way back to comics, then?

CW: Two years of breadline living led to me becoming an art teacher and I was lucky to love the job — my first five years of teaching are what made me the man I am today and were some of my happiest times — but, best of all, it gave me something I haven’t had for a long time. A disposal income! And so, I went in search of what would become my local comic store. GOSH Comics, which back then was by the British Museum. Every week I’d visit the store, make friends with the great folk who worked there, and feed my appetite for the sort of stories only comics could tell.

I was using comics in my teaching. Drawing worksheets disguised as comics. Hiding the learning in the fun. One day, one particularly vocal student who was annoyed at yet another comic-laden worksheet, called out loud, “If you’re so good a comics, why don’t you do comics?” - and for the first in years, I, too, questioned, “Why don’t I do comics?”

CW (cont’d): Here’s the thing that happened, though. That art teacher who got me to swear off comics had done me a huge favor. I’d spent the last twenty years — it had it been so long already — absorbing a much wider range of art. Including but not limited to a range of fine art, contemporary illustration, and graphic design. And, of course, my other love, cinema. Now, comic pages didn’t look like the bad Jim Lee rip-offs they did when I was fifteen.

CH: I’m curious, can you talk specifically about some of the significant influences on your style?

“That art teacher who got me to swear off comics had done me a huge favor. I’d spent the last twenty years absorbing a much wider range of art. Including but not limited to a range of fine art, contemporary illustration, and graphic design.”

CW: It was a real melting pot and many were fleeting. Seen for a moment and absorbed. But consciously, Francis Bacon, Basquait, the Japanese pop art movement Superflat. Gustav Klimt was a big one. Like McKean, it was all about contrasts and the tension between different realities. The photorealism of his portrait work combined with his decorative pattern work. And more contemporary, the fine artist who made a big impact was the late Reggie Pedro. A South London artist who died far too soon whom I discovered when he provided artwork for the album covers of Gomez, a UK indie band who were popular when I was at university. Like the others I mentioned, he did that thing where he combined abstraction alongside more recognizable reality. Unlike Klimt, however, his abstractions were born from his looking at the urban world around him. I adored his work.

CH: I’m a fanatic for Klimt for the reasons you describe. As for Pedro, he was born in the same hospital as my youngest son. He’s an artist I’ve never been able to experience in more than print, which is disappointing. I can see how he would’ve influenced you.

Getting back to your journey, you’ve described how you were inspired to pursue a life in comic books. And by then, you had developed a much broader creative toolbox than you would’ve had if you’d tried to break into the game in your early twenties. But how did it actually happen, that leap from the classroom to illustrating comic books for a living?

CW: I began posting art on comic forums and it just caught. I did short comic stories in a friend’s indie comic, ATOMIC ROBO, and that led to my first comic series, which led to another, and, after five years of doing comics at night and teaching in the day, I finally quit the day job as I embarked on a comic book collaboration with Matt Fraction. A gender-swapped cosmic retelling of THE ODYSSEY called ODY-C. Then, my journey into the comic world really began.

CH: Speaking of that journey, we should probably talk about BATMAN: CITY OF MADNESS. To do that, I’d really like to start with your relationship to the character. Personally, my favorite Batman stories, the ones that never seem to leave me, are the ones that took this grounded vigilante character and throw him against mind-mending horrors. I’m thinking BATMAN: THE CULT, BATMAN: RED RAIN, and, of course, ARKHAM ASYLUM. Obviously, I’m dating myself here. But what about you? What about Batman has appealed to you over the years?

CW: [Laughter] Hard same. As I mentioned, it was ARKHAM ASYLUM that began this all and CITY OF MADNESS is very much of a pseudo-sequel to that book. I don’t want to spoil how it’s connected, but it’s really fucking cool.

CW (cont’d): Like you, though, as much as I loved DARK KNIGHT RETURNS, it was his more idiosyncratic stories I would return to. I like Batman as something bigger and more mythic than a man in a combination of tights and body armor. Alongside ARKHAM ASYLUM, it was THE CULT, RED RAIN — indeed all of Kelly Jones and Doug Monech’s run in their nineties — and Grant Morrison’s other book GOTHIC. Batman works so beautifully with horror and dark myth.

“I like Batman as something bigger and more mythic than a man in a combination of tights and body armor. [He] works so beautifully with horror and dark myth.”

CH: It’s one of the great contradictions of his character. He’s the world’s greatest detective, grounded by facts and logic and reasoning. But those qualities seem more interesting when pitted against the extraordinary, the terrifying - the mythic, as you say

CW: One of my best-ever lessons I learned as an artist was to utilize tension. That, as an old tutor once said, was the secret of good art. The tension between shapes, colors, lines, and textures. Tension is what makes things interesting and it’s born from conflict. I think the contradiction is exactly why it does work. Though, let’s talk plainly, as much as the character is “grounded” as you say, he’s a man who dresses up as a bat and has a rogue’s gallery of many villains who are on the verge of supernatural themselves. I’m pretty bored of “let’s make Batman grounded and real” – though I did love Matt Reeves’s recent film. Batman far more should be, as you say, mythic.

“One of my best-ever lessons I learned as an artist was to utilize tension. The tension between shapes, colors, lines, and textures. Tension is what makes things interesting and it’s born from conflict.”

CH: Before I press on with CITY OF MADNESS, I have to ask, does your audience factor into the tension you try to create in your work? Meaning, do you imagine any kind of tension between what you’re creating and how the reader is experiencing it?

CW: I’m not sure about tension per se. You want there to be relationship between your work and the readers, but honestly, that relationship belongs to the reader - not to you. You can’t control how a reader responds to your work, so I find the best way to create work is to write for myself, or in the case that I’m writing for another artist, I’m writing for them and them only. If you can tell a story well to one person, then that’s your job done. Then you send it out into the world, and it belongs to everyone else.

CH: We’ve talked about your early passion for telling stories and how that manifested both as comic books and a lot of short stories and aborted novels. In other words, you’ve been writing, not just illustrating, for your whole life. And while you’ve written a couple of comic book series for others to draw, CITY OF MADNESS is your first time taking on both duties by yourself. What about the book made that such a necessary decision for you?

CW: Drawing and writing a Batman book was always the dream. The literal lifelong dream. As we talk, I’m drawing their last issue. In forty-eight pages time, it’ll be done and I’m already preparing myself for how I’m going to feel to be post-lifelong dream.

CW (cont’d): But I think there is another answer in there as to why I didn’t draw the other books, or rather why did I draw this one. The simple answer, I think, is that not all my stories are best suited to my art. Though both books, MACHINE GUN WIZARDS and BLOOD STAINED TEETH have fantastical elements which one might think would make them easy fits, both had other elements which I felt were more important. MACHINE GUN WIZARDS was a period piece and my co-creator Sami Kivela is amazing at those details. Similarly, Patric Reynolds, my co-creator on BLOOD STAINED TEETH, brings a level of our reality to our vampire book that — it being an attack on real world billionaires and a celebration of a free health care system — felt it needed.

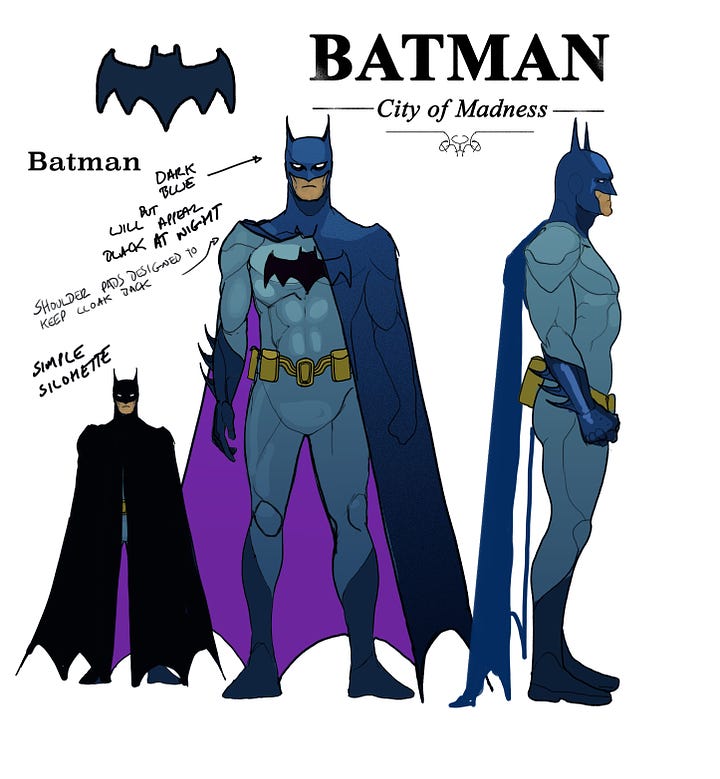

Story always has to be first, so which artist serves the story better? For Batman, it’s a cosmic horror that feels somewhat intangible. Like a nightmare you hope to forget when you wake, its edges are soft and unfocused. Of course, Batman is a character who fits into every genre from camp comedy to gritty pulp crime, but when I devised what my Batman would be, I consciously leaned towards my strengths.

CH: I’ve been lucky enough to read Issue 1 of the series now, and I have to say, it’s a stunningly beautiful piece of work to look at with several images that I feel will prove iconic after the rest of the world gets hold of this. But I think what struck me most were these beautiful little moments of silent introspection about trauma and mental health with a brief scene with Barbara Gordon also tackling the subject out loud.

CW: I find it easier to write if the stories are discussions about things I care about. BLOOD STAINED TEETH was as much about my disdain for billionaire culture as it was a rally cry for the importance of national health care. This book is about the importance of mental health and therapy. I’ve been thankfully out of therapy for many years now, but my time in it made me the person I am today. I look at my life divided into two - before and after therapy. So as much as this is a love letter to a character who gave me the life I have, it’s also a hymn to the thing that in many ways saved me - wrapped up in a fun exciting horrifying adventure. This isn’t a TEDTalk, after all.

CH: [Laughter]. Absolutely. But that said, thank you for sharing that insight into your own mental health journey and how it influenced CITY OF MADNESS.

“I look at my life divided into two - before and after therapy. So as much as [BATMAN: CITY OF MADNESS] is a love letter to a character who gave me the life I have, it’s also a hymn to the thing that in many ways saved me - wrapped up in a fun exciting horrifying adventure.”

Okay, so this book is, in your words, a cosmic horror. I’m loathed to bring him up, because it’s such an overused and, frankly, lazy reference for anyone to make these days, but I found your book very Lovecraftian in spirit. Yet your work, in general, eschews the kind of darkness typically associated with that description in favor of vivid, sometimes even neon colors. You might just be Lovecraft and Bowie’s love child. This remains true with CITY OF MADNESS, an apparent contradiction I loved here.

CW: One of my favorite horror films of recent years was MIDSOMMAR - a film even more terrifying becomes of the glorious sun that lights up every horrific moment. So, absolutely why not a neon noir cosmic horror?

I think that’s what has made this interesting to me. I’m not doing a Lovecraftian story as much as I’m exploring what my cosmic horror is like. You always have to stay true to yourself as a creator, rather than shifting and changing, in a misguided attempt to find oneself. Whatever you do - do you. My work is colorful, and it’s interesting to me to apply that style to lots of different genres.

CH: We’re almost at the end of our conversation. I want to keep talking about Batman, though. A moment ago, you said drawing and writing a Batman book was your literal lifelong dream. I know you’re not quite finished with that process yet, but I’d really like to ask: what has having your dream come true taught you about Batman and yourself as a storyteller?

CW: It might sound trite, but it’s taught me how important love is. Or, perhaps, what I mean is, it’s important to put yourself in your work. To be as personal as possible. Despite this being a Batman comic — that being a character owned not by myself but by a mega-corporation — I’ve treated this as a creator-owned book. I love this character, I love this story, and I love that I’ve been given this opportunity. Likewise, I’ve been very passionate on social media, and the response has been incredible, and I honestly think it’s been my love and passion that folk have responded to as much as the fact that this is Batman. Make every story as personal as possible. Inject yourself and love into it. After all, nothing makes horror — cosmic or otherwise — sing as loudly as love.

You can find Christian Ward on Twitter or learn more about him and his art at his website. BATMAN: CITY OF MADNESS’s first issue is out now from DC Comics.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world: