Guys, What If Peak TV Broke Our World?

Or: How the relentless proliferation of 'content' on our TV screens has helped turn our reality into a lonely, anxiety-inducing multiverse of shit

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall;

All the king's horses and all the king's men

Couldn't put Humpty together again.

-Mother Goose

It’s time to make a terrible, shameful confession. Despite coming of age in the Nineties…[deep breath]…I never watched “Friends”. There, I’ve finally said it. Oh, I caught maybe a dozen episodes when it was on the air – it was something that played in the background, typically because a girlfriend insisted on it – but sitcoms weren’t really a big part of my life back then. By the time they were, Rachel and Chandler and Joey and Monica and Chandler and Phoebe had retired to electric pastures in the sky. I think I watched the finale, but I can’t be sure. I know how it ended either way because every single human being I knew was talking about it after it did.

“I feel attacked by television.” This is my new explanation as to why I’ve largely given up watching new television.

“There’s too much of it,” I say. “I can’t keep up,” I say. “I’m not enjoying a lot of it anymore anyway,” I say.

But this is only the tip of the iceberg, so to say. My problem goes much deeper, and as I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about it recently, I’ve come to some pretty troubling conclusions. Troubling because if I’m right, the future of film and TV is even more dire than we all already say it is.

Slight correction to an earlier statement. I have indeed watched “Friends”…now, that is.

Earlier this year, my wife and I decided to watch the pilot. Unlike me, she’d actually seen every episode and had no intention of giving more than that first episode any of her precious time. She was chasing a quick nostalgia hit, nothing more.

The pilot was…okay? A couple of decent jokes, but it was clunky as hell. The actors seemed confused who their characters were, which isn’t exactly surprising given they didn’t yet. I honestly couldn’t understand why it had become such an immediate hit. So, I suggested we watch another to find out. My wife didn’t protest, despite her precious time.

This time around, we both laughed. All the way through it. By the credit coda scene, we decided not to stop.

Currently, we’ve just started Season 3. I haven’t had this much fun watching a television series in a long time. The why of this is part of what I find so troubling both as a TV writer and a TV viewer.

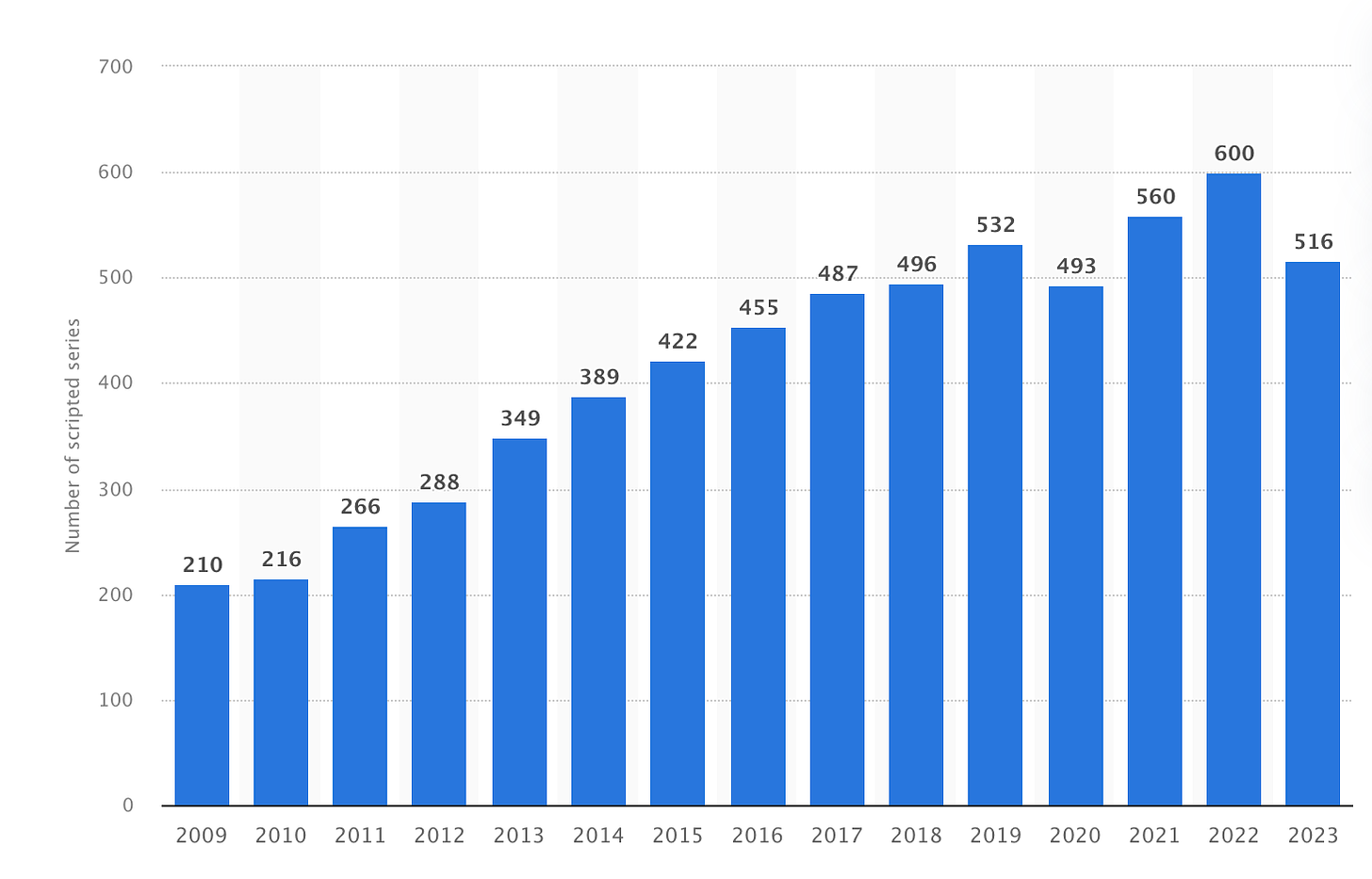

I’m just one person and this is not an arts newsletter with infinite resources (meaning, my time). But I’ve done some research, and something you might find interesting is that in 2022, 600 scripted television series were produced by Hollywood. Five years earlier, that number was 487. The oldest information on this matter that I can find without going full Dick Tracy is from another seven years before this, 2009, when 210 script series were produced.

Another way to put that is that in thirteen years, the rate of television production in the United States almost tripled.

Most people describe “peak television” as a high point in Hollywood, when more great shows were produced than at any other period in history. But I’ve come to regard it as, instead, a period of grotesque overproduction that churned out a disproportionately lower number of TV series that can endure the test of time by comparison to twenty-five years earlier when “Friends” premiered in 1994.

The argument was that this explosion in TV production was to support a new global market suddenly capable of accessing this amount of television via streamers. But at the same time, domestic production outside of America, especially for streaming distribution, experienced a similar growth spurt. There was suddenly more TV than any rational civilization could consume.

For context, between 2009 and 2022, the United States population grew from 306.8 million to 333.3 million. That’s an 8.3% change. But to satisfy this growth, the same population in 2022 was given access to roughly 300% as many U.S. TV series as they had been thirteen years earlier. There’s no way to take into account all the international series that were also put before their eyeballs, but I’m willing to bet the real number of viewing opportunities for them went up closer to 1,000%.

But who was watching all these series?

The answer: everyone…and no one.

Back in 1994 when “Friends” debuted, I had just graduated high school. The show was so immediately successful that every young woman I tried to ask out had the “Rachel haircut”. Everywhere I turned, people were talking about “will they or won’t they?” about her and Ross. Every guy suddenly delivered sarcasm just like Chandler. People quoted the series to me even if I didn’t understand what they were doing at the time.

It was relentless.

This is what we call a zeitgeist moment.

Whether you liked it or not, if you were alive in the Nineties, the cast of “Friends” was now part of your life. Maybe that’s why I didn’t bother watching. At the time, I felt like I didn’t need to.

I wish I could find the rate of scripted TV production in 1994, when “Friends” premiered, but I’m not that savvy. I have to look at a list of titles on the air that year and make some crude calculations to get to a number roughly around 125. What this doesn’t take into account is how many pilots were shot, which I suspect places the production number more in the space of 200 as I already showed was more or less the rate of 2009 fifteen years later. But what I’m about to say only concerns what made it to air.

In 1994, there was a very good chance that any person I met on the street was watching at least one of the ten or so series I was watching. If I had been watching “Friends”, the odds of this happening would’ve climbed dramatically.

Put another way, in every year of my life until the explosion of cable TV that arrived around 2000, I shared numerous things in common with every single person in America whether we realized it or not. We were all part of the same conversation. We were an unwitting community.

This is the reason why film and TV worked so well throughout the 20th century. Both were communal mediums. Once upon a time, there were only a handful of films released every week. We all had to partake in those or risk missing out. Television and its handful of channels meant roughly the same. We all watched the same news broadcasts until cable took over. Language flattened across geographical distances and even changed this way because of how common the viewing experience was. Popular styles changed, such as haircuts. How we saw ourselves and talked about difficult subjects was even literally on the table, as Norman Lear’s sitcoms repeatedly proved when they became essential supper-time viewing.

The moving image has always been something we did together. It was the glue that held everything together during the last century, you might even say.

I began to notice something was wrong around 2010. I was working in Hollywood by then, and suddenly everyone wanted to work in television. In fact, I would have my own TV series on the air within a few years. The medium was increasingly seen as cool, not that place you went to slum when your feature career didn’t work out. But as this was happening, I realized the number of series we were all watching at the same time was also fragmenting. Even more concerning, what “Hollywood” was watching didn’t necessarily align with what the rest of the country was watching. Prestige and awards began to replace eyeballs as a metric for success, which is not a sustainable business model, I think.

Consider “Mad Men”, which premiered in 2007. It’s generally considered one of the greatest TV series ever produced. But for all that “success”, its viewership was incredibly low. For example, in the series’ first season, the vast majority of the episodes didn’t even crack 1 million viewers.

At its peak, “Mad Men” reached 4.7 million viewers for its Seasons 5 and 6 premieres – after four celebrated seasons and endless awards to collect even that many eyes. But every other episode of these two seasons? They had fewer viewers than every episode of a network TV series I created, “Dracula” (2013), a TV series generally considered to be a failure with most audiences – and so disappointing even for me, its creator, that I’ve never even watched the damn thing.

What I’m trying to say is, there’s a reason Jon Hamm, despite how brilliant he is — and I am a huge fan — never really became a household-name actor. Because there were almost no households across America actually watching him do some of the best work of his career on “one of the greatest TV series ever produced”.

This was all before the streamers changed everything around 2013, when Netflix debuted “House of Cards” and “Orange Is the New Black”. At that point, all bets were off. The number of series produced in the US and abroad began to skyrocket until there was almost nothing left to connect us anymore by way of what we were all watching as a culture. For every “Game of Thrones”, there were, it seemed, twenty series that few except their casts and crews even knew were on the air.

A friend just said they read about a TV series that was canceled after seven seasons, except this friend said he’d never heard of the show. This concerned him because he’s a TV writer and has no idea how he was so ignorant of this allegedly successful series’ success. Then, he confided, this happens to him all the time.

But the same thing happens to me, too. I visit industry news sites every day and read what’s happening in the Hollywood film/TV business. And on average, I’d say I learn about the existence of two TV series a week only after they’re canceled after multiple seasons on the air.

There’s so much TV, even reading about TV every day isn’t good enough to keep up with all the TV that’s out there.

Imagine for a moment what your life would’ve been like in, say, 1994 when “Friends” debuted. If you were a middle-aged homebody with nothing else to do with your life, you might watch ten scripted series a week. Hell, Thursday night’s “Must See TV” line-up was five of them for a lot of people. In almost every case, you committed to watching these series for more than twenty episodes - or, more specifically, about 240 episodes of television in a year. This commitment was long-term and had a season conclusion. It would then be followed by a brief, usually three-month-long break, then the series would typically return. You built a relationship with the characters you watched, you counted on them coming back, and you didn’t have to wait too long for them to do so.

There was something else different about your life in 1994, too. Most of these series were not overly serialized. Many were procedurals or procedural-adjacent. Meaning, if you missed an episode, you were not going to lose your place in the story and feel some need to abandon it. One reason for this was digital recordings and streaming didn’t exist yet. You had to either watch the episode in real-time, tape it on your VCR, or just keep up despite having missed an episode. Asking audiences to keep up with too much plot nuance over several episodes was just not realistic.

My point here is this: In 1994, you had long-term, generally reliable relationships with a limited number of series that made limited demands of you and your brain beyond having a good time.

Today, by contrast, we’re asked to keep up with TV series that last six to eight episodes, many of which are limited series rather than ongoing ones, that multiply like Mogwai at a pool party until you can’t even remember which ones you wanted to watch, and which get canceled with inexplicable randomness so that we have zero confidence if we start watching a story that we’ll ever reach any kind of conclusion. Oh, and if they do return, the new season might take twelve or eighteen months to show up.

What I’m describing is a scenario where we’re asked to hold in our heads a profound amount of narrative information, far more than we ever have before, with the bonus of being told we have to quickly move on to the next title or risk missing out on the latest sexy thing or the discourse that comes with it. It’s fractious and disorienting. It’s anxiety-inducing. It’s why I now I say I feel attacked by television.

There’s something else that culturally happened right around the time that peak TV began to take off and streamers kicked off their takeover of film and TV. I’m talking about the proliferation of social media platforms.

Initially, the argument was they brought us together. And hey, maybe they did for some of us. But each quickly became a place to disseminate information in what you might call packets. We began to experience people’s lives in fragments, so to say, just like we were being asked to now experience television and even films (as they began to replicate TV’s increasingly serialized nature). Everyone and everything became a packet of McInformation to quickly consume before moving on. This was true for how we acquired our news now, too. Instead of picking up a newspaper, visiting a news site, or sitting through a cable news show to learn about the world, it was now available to us in an avalanche of convenient headlines and snarky opinion commentary from everyone we know who was also doing the same thing.

I describe this phenomenon, on social media and elsewhere in film/TV, as the Great Fracturing. Before the internet, reality was our local neighborhood or maybe the whole city were lived in. By the time “Friends” debuted, that reality began to expand. By the time the series concluded, reality was shattering into more pieces than we could even count. And, by the time streaming replaced broadcast/cable television and movie theaters as the chief mover of the moving image in the world, none of us understood what reality meant anymore. We had to create our own, and typically we did so by searching for or creating it on the internet – basically, what I’m describing is a modern-day reimagining of the Tower of Babel.

There are a lot of reasons why global mental health struggles have exploded in the 21st century. A lot of the blame is put on mobile devices, and I don’t see any reason to disagree. But I’ve come to believe the mobile device is symptomatic, not the root cause.

The root cause, for my money, is the proliferation of information. Reality has simply become too large for most of us. We live in a multiversal hell now that is making us all more and more unhappy and is slowly killing us off if you look at the climbing mental illness and suicide numbers across the world.

Peak TV isn’t to blame for this, of course, but it’s certainly contributed significantly to this. But nobody seems ready to acknowledge it.

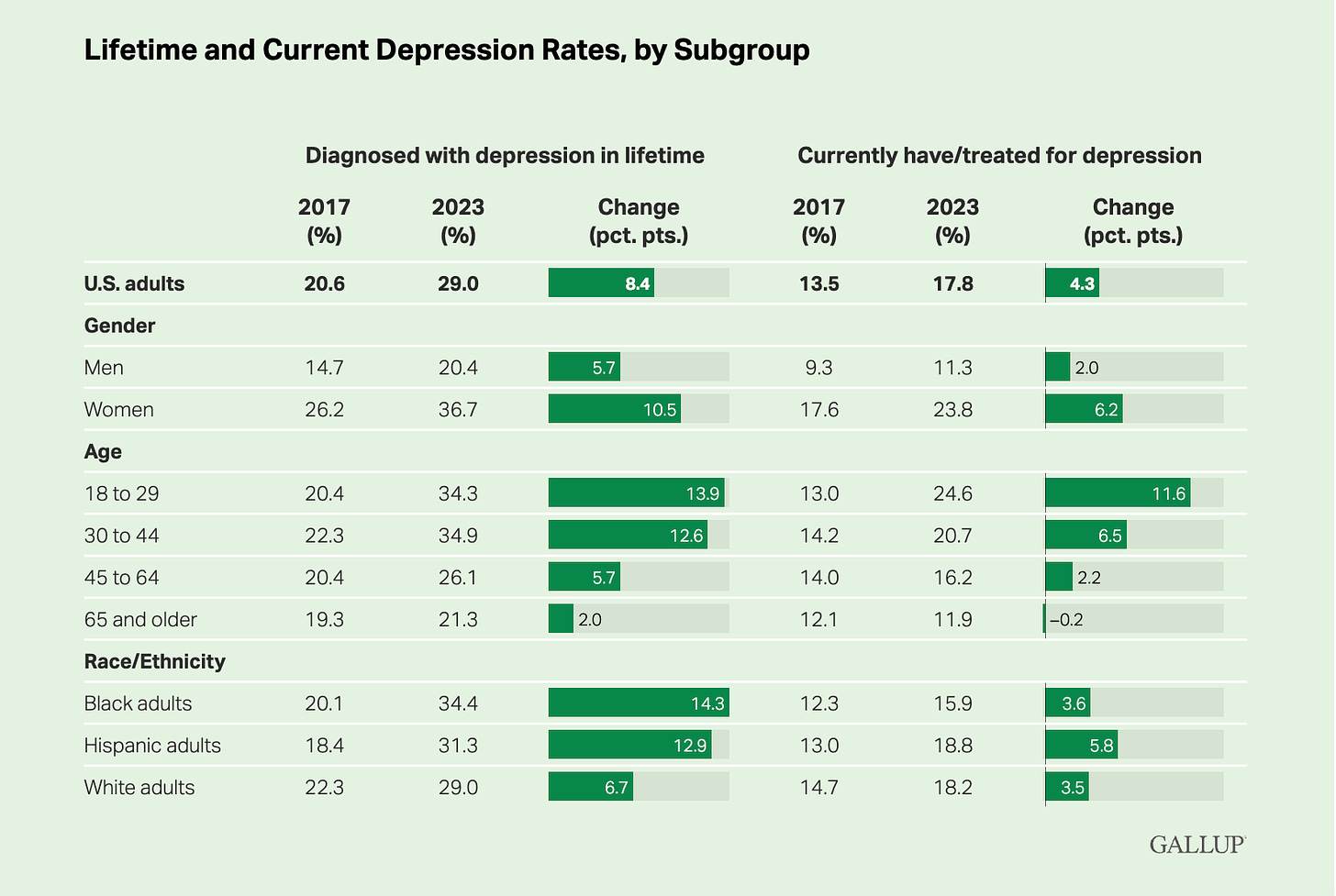

Here’s a Gallup poll from last year that evaluated the differences between 2017 and 2023 when Americans were asked two questions: Has a doctor or nurse ever told you that you have depression? and Do you currently have or are you being treated for depression? Look at the numbers for the two youngest groups!

Regarding suicide, it’s no less grim in the U.S. After years of steady declines, suicide rates increased 37% between 2000-2018. They decreased 5% between 2018-2020, only to again begin to climb and, in 2023, cross 50,000 in one year for the first time. But what we’re talking about here is an almost 40% jump in suicides in two decades. Two. Decades. I don’t see how it’s possible to read these numbers and not despair for where we’re heading as a species.

My mother was borderline agoraphobic toward the end of her life. She preferred to remain inside and watch “Blue Bloods” and “Law & Order” and “NCIS”. She’d constantly asked me if I watched any of these shows. She had nobody to discuss them with - which only made her feel even lonelier.

I think about this all the time when I consider what television has become and what cinema has become as it’s shifted more and more to the conveyor belt of quickly forgotten nothing that is most streaming platforms.

We’re all watching something, but we’re not watching any of it together anymore.

There’s a saying: If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? But the question I find far more critical to where we are as a civilization is: If a tree falls in the woods and you hear it happen but have nobody to tell about it, who gives a fuck?

Do you know why I look forward to watching “Friends” every night with my wife? Because I do, if you’re wondering. I’m more excited about watching it than anything else currently on TV.

I sit down after we put the kids to bed and find myself spending time with characters I like, who will be around for twenty-four episodes per season, who will be around for ten seasons in total. This is a long-term relationship that won’t be canceled almost as soon as I start watching it. Hell, even the credit sequence/theme song adds to the experience. I’ve never once pressed “skip ahead” when the Rembrandts start singing, “So no one told you life was going to be this way.”

There’s security in this. There’s certainty in an unstable, generally miserable TV landscape where everything new now feels disposable because it even is to those who own it (studio heads regularly erase shows you love from streamers to save a penny). Where whatever is hot today will be replaced next week like old produce on a supermarket shelf, whatever came before already a dwindling memory. Where everything feels so mind-shatteringly multitudinous — let’s just call it white noise — that I find myself retreating from it to something I don’t experience like an assault on my mental health just for the sake of enriching the very people ruining art forms I love so much.

This is the consequence of mass-manufacturing content rather than art.

There’s another reason I’m enjoying “Friends”. It’s easy to say I’m being nostalgic, and I am – but not in the way you think. I’m not nostalgic for a show I loved such as how I feel about, say, “Buffy the Vampire Slayer”. I’m not nostalgic for something I missed out on because I watched plenty in the Nineties I could be doing that with instead.

No, I’m nostalgic for the quiet that came with existing during the last period in history before the world itself became too big for any one person to try to comprehend without going a little mad. This exponential growth broke our reality and, in the process, blew apart all the communal bonds we once valued so much. I worry we’re living through all the King’s men discovering there’s no putting it back together again.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Every election year I revisit The West Wing (yes, even the flimsy 5th season post Sorkin). I’m about to rewatch it.

But I came here to say that, like social media, television — or whatever we’re calling it now — became specialized. There’s a Cat Fancy for everyone. If you like apocalyptic mutant zombie infant deathmatches…there’s a show for that. And, no, you don’t have to watch it. Though, in that same breath, we used to think good writing/tv/film rises above and becomes part of the zeitgeist. But that wave doesn’t exist as more than an echo for a small subset of people anymore. Such is getting what we always wished for: everything.

Think about some of the most praised and zeitgeist-popular shows of the last five to ten years. Barry, The Good Place, Fleabag, The Leftovers, Atlanta, all gone from the national consciousness. What are the TV shows of the last ten years that have remained vital? Game of Thrones, probably. Succession seems to have faded already. All great shows. Some of the greatest of all time. But, poof, they're gone. Meanwhile, The Office and Friends still dominate. I think we used to have marriages with TV shows. Now we just have passionate binges with shows and then move on to the next. I mean—give me House, M.D. over almost anything new.