What If the Only Way to Protect Films and TV Series from Streaming Platforms...Is to Break the Law?

Hollywood has a long history of scrapping films and TV to save money, but the recent purging of "content" from streamers poses a new kind of threat to our cultural heritage

“We have to make it crystal clear to the current legal owners of these films that they amount to much, much more than mere property to be exploited and then locked away. They are among the greatest treasures of our culture, and they must be treated accordingly.” – Martin Scorsese

It’s estimated that 75% of original silent-era American films have been lost. There’s probably no way to know for certain how many international silent films have also been lost, given the scope of such an accounting, but I’ve seen estimates around ninety percent. You might say, “Well, that was a long time ago. We’re talking a century. Shit happens.” But an estimated half of all American sound films produced from 1927 to 1950 have also been lost, too. These are staggering blows not just to cinema history, but also human history. These films are the stories of us, anthropological records, good and bad. Which makes it all the more horrifying that American studios and streamers such as Warner Bros. Discovery, Disney, and, most recently, Paramount1 have begun doing the same thing to contemporary films and TV series – erasing art from our cultural heritage in acts that, if they were committed by the Taliban against museums, we would be decrying as the acts of monsters.

IT’S ALL ABOUT THE BENJAMINS

The theory is simple. Streamers need to cut costs to become profitable because they are failed distribution experiments — quite possibly “the crypto of the entertainment business” as Steven Soderbergh suggested to VULTURE — and one route to accomplishing that is by removing content specifically made for streaming from their platforms. The reason being, streamers must pay to license what they provide to subscribers, even if the film/series is owned by their parent company.

If you’re not in the industry, this might be a bit of a head-scratcher, I know. Even titles that are owned in-house must be licensed, as ABC News recently explained.

That’s why NBCUniversal (the parent company of CNBC and NBC News) had to pay itself $500million to stream Universal TV’s “THE OFFICE” on Peacock and Warner Bros. Discovery paid $425 million for the streaming rights to the WBTV-produced “FRIENDS”.

The more of these (allegedly) underperforming films and series that are removed from the streaming platforms, the less the platforms have to pay out. Profits go up.

This is basically why more than a hundred titles have been removed from platforms such as HBOMax and Disney+ and soon will be from Paramount+. Nobody knows which of these films or TV will ever see the light of day again. Many likely never will.

Here’s a Disney-specific explanation from VARIETY, to help you understand the situation better:

In an SEC filing [on June 2nd, Disney+] said that on May 26, 2023, it removed “certain produced content” from its direct-to-consumer streaming services. As a result, Disney will record a $1.5 billion impairment charge in its fiscal third quarter financial statements “to adjust the carrying value of these content assets to fair value.”

Disney said it’s continuing to review content on streaming platforms and “currently anticipates additional produced content will be removed from its DTC and other platforms, largely during the remainder of its third fiscal quarter.” As a result, Disney currently estimates it may incur further impairment charges of up to about $400 million related to produced content.

You might ask yourself what an impairment charge is, and rightly so. An impairment charge is an accounting term for an asset that’s no longer as valuable as it may have once been. According to most sources I found, it usually occurs during unforeseen challenges that negatively affect a company. In Disney’s case, I assume this means gross incompetence colliding with accounting abuse.

Because let me put that another way: Disney took the art it commissioned, that it induced artists to spend years of their lives producing with promises of residuals and immortality on our screens, and shit-canned it so it could take some tax write-offs.

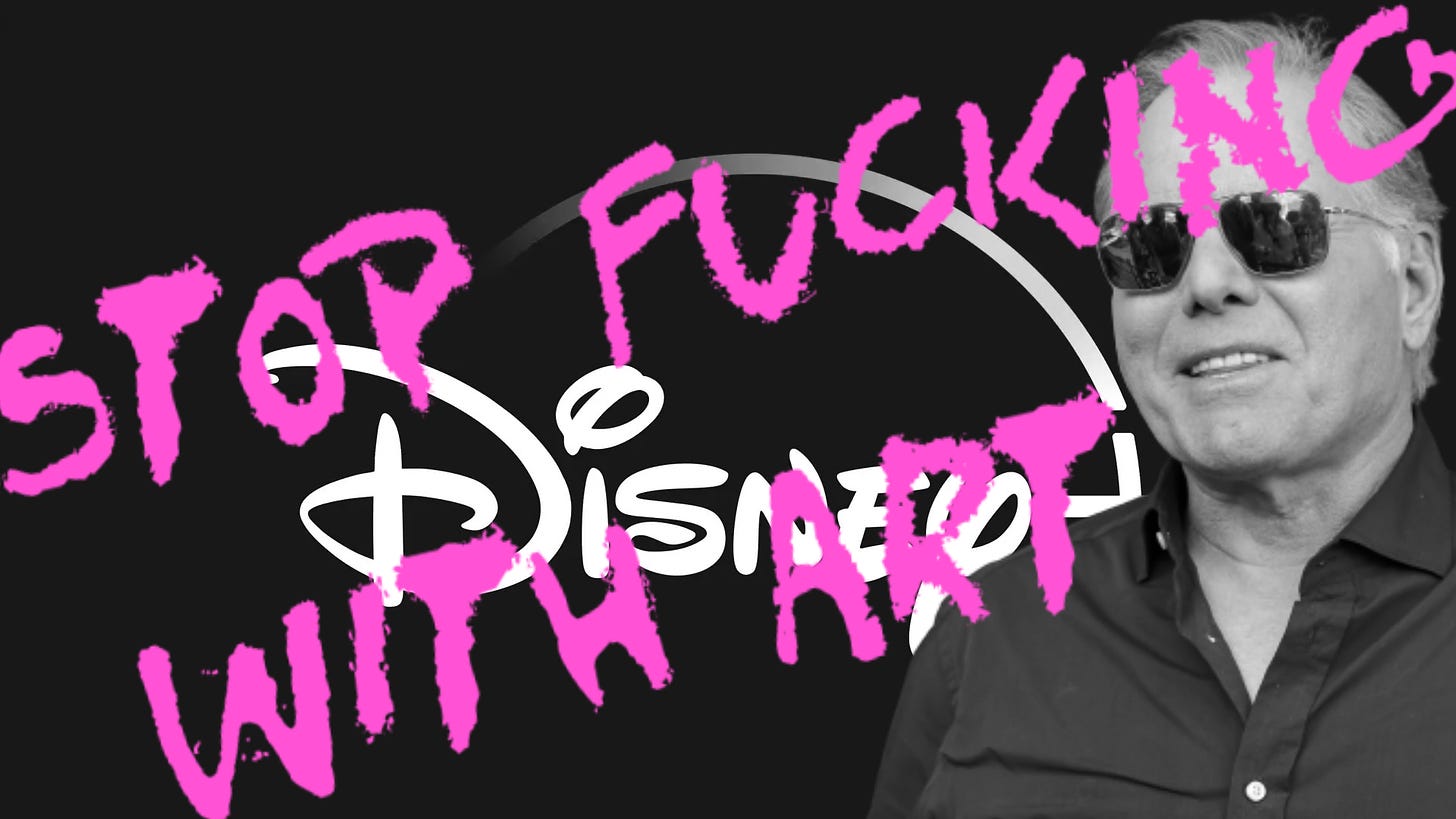

Warner Bros. Discovery, under the leadership of David Zaslav — a person who seems to have the kind of disdain for the film/TV business that Donald Trump has for American democracy — has done similar, but gone the extra mile to also throw away unreleased films such as BATGIRL because, he argued, it would damage DC’s brand to actually release it.2

Yes, kiddos, BATGIRL might have destroyed the otherwise unblemished reputation of the DCU more than rebooting it every eighteen minutes and, most recently, releasing a film starring a serial abuser who has literally kidnapped other human beings.

In reality, I don’t know a single filmmaker who speaks favorably of WB Discovery anymore. It’s the studio to run from if at all possible, which is solely because Zaslav’s malignant approach to art has alerted everyone in the industry that WB Discovery is now an unreliable partner that will potentially napalm your art and steal money from you (because licensing fees and residuals are part of the deal that is struck with artists, though this article will primarily focus on the art side of this issue).

THE HISTORY OF LOST FILM (OR: THE HISTORY OF HOLLYWOOD’S CONTEMPT FOR ART)

This isn’t the first time Hollywood made a decision to put profits over art.

Before there were televisions at home, before home video, before DVDs, and Blu-rays, and the streamers, a sound film’s relevance pretty much ended with its theatrical run. There were exceptions, sure, but for the most part, films lost their profitability when they were finally shelved.

In the case of silent films, we’re talking about an entire era of cinema that was deemed antiquated garbage almost as soon as sound entered the conversation and forgotten about on purpose. Given that many of these films were made by Black people featuring Black performers (known as “race films”)3 — an early contribution to cinema largely erased from history books because of these purges — you can understand my concern about the current threat to our cultural heritage.

So, what did this all mean in practice for these films that had been deemed no longer profitable?

Film preservationist Robert A. Harris — one of the heroes who helped restore my favorite film LAWRENCE OF ARABIA (1962) — has explained it this way: "Most of the early films did not survive because of wholesale junking by the studios. There was no thought of ever saving these films. They simply needed vault space and the materials were expensive to house."4

Other studios discovered they could make even more money off their dead films by recycling their reels for their silver content. Points for recycling…I guess?

Then, there’s the cinematic horror story of Technicolor two-color negatives from the 1920s and 1930s. Wikipedia, take it away:

[Many of these] were thrown out when studios simply refused to reclaim their films, still being held by Technicolor in its vaults. Some used prints were sold to scrap dealers and ultimately cut up into short segments for use with small, hand-cranked 35 mm movie projectors, which were sold as a toy for showing brief excerpts from Hollywood movies at home.5

In short, it’s not surprising that Hollywood studios and streamers are once again intentionally targeting our cultural heritage for profit. It’s in their DNA.

In cases where films were institutionally destroyed in the past, there is almost no hope of recovering them. You have to pray a pile of film canisters is someday randomly rediscovered in someone’s barn. I’m not joking. This literally happened in the case of THEIR FIRST MISUNDERSTANDING, a 1911 film that was found in a New Hampshire barn in the early 2000s – nearly a century after it was initially released.6 It represents the first appearance onscreen of film legend Mary Pickford.

Even when these lost films are rediscovered, restoring and preserving them for posterity is difficult and expensive. David Kehr wrote the following in THE NEW YORK TIMES back in 2010:

A great deal of important material — not just features but shorts, newsreels, experimental work, industrial films, home movies and so on — remains on unstable nitrate stock, and must be transferred to a more permanent base before the films turn to goo. And once the endangered material has been stabilized (the preservation step), it often must undergo an even more expensive process of restoration to recover its original luster: the removal of dirt and scratches, the replacement of lost footage or missing intertitles, the cleaning up of degraded soundtracks.”

“Film preservation is a Sisyphean task,” [said Joshua Siegel, an associate curator at the Museum of Modern Art], an indisputable statement, but not a completely pessimistic one. The rock is always rolling downhill, as chemical decomposition claims more footage each day. But thanks to evolving technology, preservationists possess ever more powerful tools to help them push the boulder back to the top.

But there is a monumental difference between what Kehr describes here — a process that Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, and countless other passionate cinephiles have invested time and fortunes into in order to safeguard our cinematic legacy for future generations and as historical artifacts to be studied — and what so many streamers are doing today.

Because these once-lost films existed in the physical world at one time or another. They might’ve been printed on nitrate stock before the early fifties, dangerously unstable, but they could be held with human hands in some form or another. They were then distributed across the world, stored in basements and museums, and kept as personal possessions. Consequently, there was — and remains — the opportunity to archeologically rescue them from the corporations that had tried to reduce them to nothing but dollars on a spreadsheet - and in doing so, resurrect our past, too.

But today, films and TV produced for streamers very often do not exist in a physical form. Most often, there isn’t even physical media such as Blu-Rays to collect and learn from and treasure.

As a result, there has been the expectation from the artists who produced these works that they would remain available in their digital states instead. They would be safe in the mythical cloud that surrounds us like the Force or Holy Spirit, for all intents and purposes. This, we’ve now discovered, was our gullibility at best or a corporate trick at worst. Probably both.

Because these films and now TV series are being wholesale junked once again by studios and streamers, sometimes permanently sealed away in vaults even more mysterious than wherever the Ark of the Covenant wound up at the end of RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK.

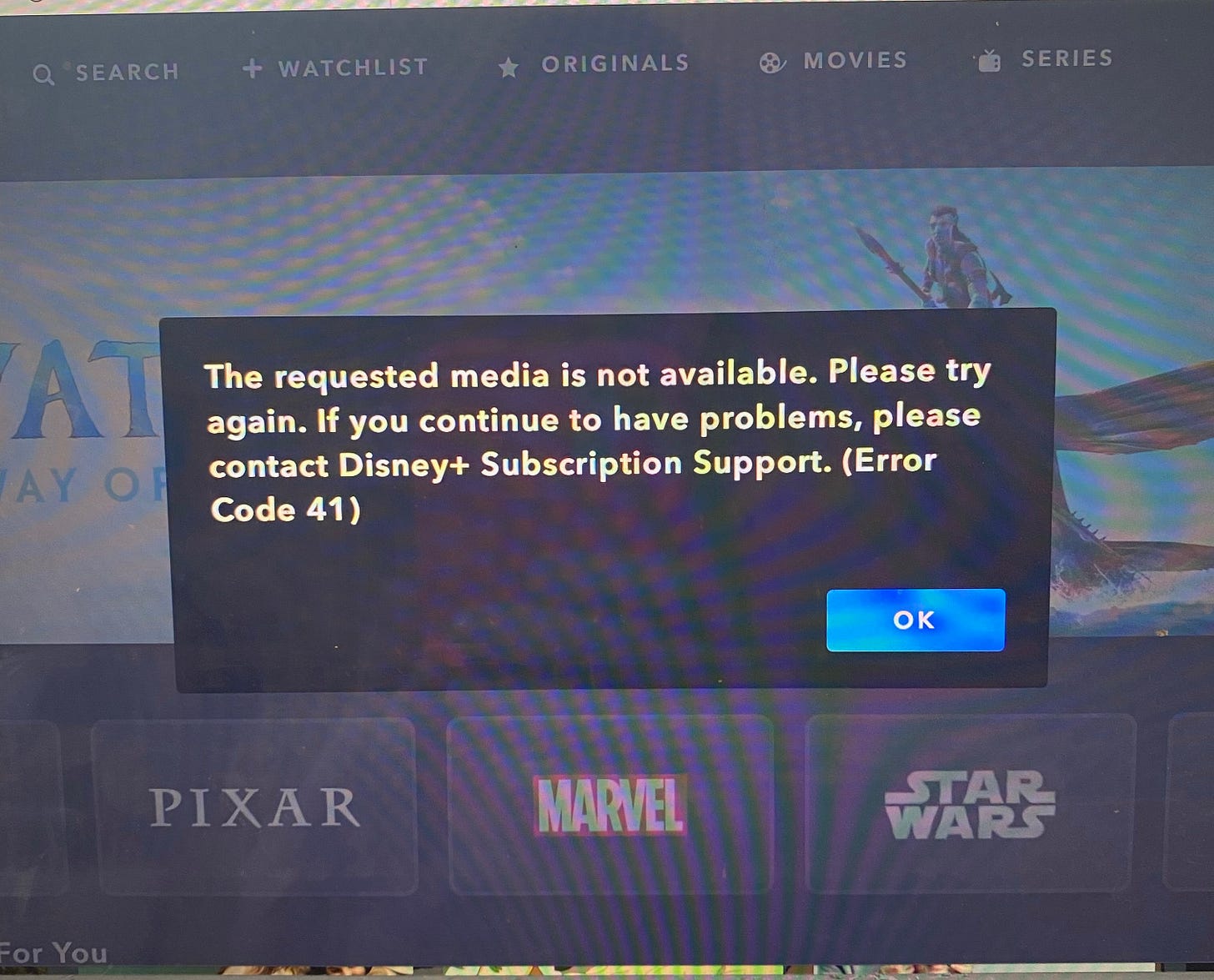

Sickeningly, filmmakers are being left unable to even watch their own films and TV series because, voila, they no longer exist anywhere. There’s no proof they even existed outside of Internet pages recounting their brief time in the sun. For example, here’s what happens when I go to watch my sister-in-law Kara Holden’s film CLOUDS on Disney+, for which she was nominated for a Best Original Screenplay award from the Writers Guild of America (it was one of the films the streamer purged as a tax write-off):

“CLOUDS was released in October of 2020 and unceremoniously purged from existence in May 2023 making it available to watch for a grand total of thirty-one months,” my sister-in-law told me when I asked her about this. “Meanwhile, I first started working on CLOUDS in April 2017 and it came out in October 2020 - meaning I worked on the film for forty-three months. So the time it was given to exist is almost a year less than the time it took me to help create it…how insane is that? And [others] working on it for years longer than me. There is just something so horribly wrong about that.”

At least CLOUDS existed for thirty-one months. “GREASE: RISE OF THE PINK LADIES” premiered on Paramount+ on April 6th of this year and finished its ten-episode run on June 1st, less than a month ago. It wasn’t just canceled by the streamer at that point; on June 23rd, it was announced that it and numerous other recent titles, including “STAR TREK: PRODIGY”, were being purged from the streaming platform for tax purposes. More impairment charges. Meaning, “PINK LADIES” has existed for less than three months and soon won’t at all in any form except our memories of it.

“PINK LADIES” creator Annabel Oakes expressed her anguish over the news via Instagram Stories:

In a particularly brutal move, it is also being removed from Paramount+ next and unless it finds a new home you will no longer be able to watch it anywhere. The cast, my creative partners, and I are all devastated at the complete erasure of our show.

The complete erasure of our show.

Studios and streamers are now not only wiping away the work of artists and those artists’ ability to profit from their work according to the expectations of their contractual agreements – they’re endangering and actively destroying our historical record for profit.

THE FRAGILITY OF COMPUTER SERVERS

There’s something else to consider beyond corporate malice when it comes to protecting film and television for future generations and study. Even if streaming platforms decided to turn back from their current course, there is no getting around the fact that servers are a notoriously dangerous way to ensure the preservation of any work of art. The story I’m about to tell illustrates why trusting streamers — trusting any corporate entity — to preserve our cultural legacy as data alone will inevitably lead to a new wave of unintentionally lost films.

In 1998 while deep into production on TOY STORY 2 (1999), a Pixar employee typed the command code "/bin/rm -r -f*" in the computer system where the soon-to-be-released film was kept. This command was meant to trigger a localized deletion — basic housekeeping, really — but the employee accidentally input it into the root directory.

The result: they deleted some 90% of the film.

No worries, there’s a back-up server, right? Except it wasn’t working right.

Yep, we’re talking tens of millions of dollars in work down the drain.

Well, almost.

Because TOY STORY 2’s supervising technical director Gayln Susman had given birth six months earlier and was working from home. Which means the new mom had the film on her own server - thereby saving TOY STORY 2 as we know it from being permanently lost.

TOY STORY 2 went on to gross $512 million at the global box office thanks to Susman. This month, Disney fired her.7

There are many reasons I share this bit of film history - chief amongst them to make sure you understand that a film or TV series being removed from a streamer’s platform far from guarantees it is otherwise being digitally safeguarded and immune to human error and technological failures. It’s not necessarily waiting there to be recovered someday, I mean. This is why physical media as a means of protecting film/TV from being lost is so important.

AN ILLEGAL, BUT MORAL SOLUTION?

For years, I railed against a family member who regularly, even gleefully illegally downloaded films and TV series. Otherwise known as digital pirating. It didn’t matter to him that a family member of his worked in the industry that he was stealing from, that actions like his, around the globe, were harming artists like myself.

But today, in this new landscape in which everything Hollywood creates has been recategorized as “content” and can be stolen from its creators, permanently locked away, even outright destroyed as if it never existed in the first place, is there not a moral obligation to protect and preserve these works of art by any means necessary - even if that ultimately means illegally downloading them?

Now, I’m not arguing for breaking the law in any way (though I will emphasize that screen-recording for personal use is still completely legal). This is all a thought exercise, nothing more.

But ask yourself, if you found out that the Louvre’s directors were about to set fire to a wing of the museum as a tax write-off, wouldn’t you expect Parisians to storm the building and carry off whatever they could to protect the world heritage contained within its walls?

Wouldn’t you join them?

Almost every filmmaker I queried about this responded in the same way: piracy was indeed morally justified if we’re given no other choice as filmmakers and as a culture. As quickly as that reply came, they all also cautioned it was “hard to put that one back in the box”, which is very, very true. The idea honestly terrifies me, which is why I’m not actually advocating for anyone to illegally download anything produced and distributed by Hollywood streamers. This is, as I said, only a thought exercise…for now.

A FINAL WORD FROM MARTIN SCORSESE

I’ll leave you with this quote from Martin Scorsese, one of the foremost cinema activists in the world and one of our greatest living filmmakers. It’s taken from “Il Maestro: Federico Fellini and the lost magic of cinema” (HARPER’S, March 2021).

Everything has changed - the cinema and the importance it holds in our culture. Of course, it’s hardly surprising that artists such as Godard, Bergman, Kubrick, and Fellini, who once reigned over our great art form like gods, would eventually recede into the shadows with the passing of time. But at this point, we can’t take anything for granted. We can’t depend on the movie business, such as it is, to take care of cinema. In the movie business, which is now the mass visual entertainment business, the emphasis is always on the word “business,” and value is always determined by the amount of money to be made from any given property—in that sense, everything from Sunrise to La Strada to 2001 is now pretty much wrung dry and ready for the “Art Film” swim lane on a streaming platform. Those of us who know the cinema and its history have to share our love and our knowledge with as many people as possible. And we have to make it crystal clear to the current legal owners of these films that they amount to much, much more than mere property to be exploited and then locked away. They are among the greatest treasures of our culture, and they must be treated accordingly.

If this article added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-news/paramount-plus-removes-grease-star-trek-prodigy-queen-of-the-universe-the-game-1235522633/

https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/warner-bros-discovery-content-write-off-batgirl-q3-earnings-1234775731/

https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/6845-black-cinema-at-its-birth

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/international-press-academy-honor-motion-54879/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lost_film#cite_note-4

https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/movies/2013/09/21/newser-film-history/2846483/

https://www.ign.com/articles/disneys-pixar-layoffs-include-producer-who-saved-toy-story-2-and-lightyear-director

“Piracy is almost always a service problem.”

-Gabe Newell of the video game platform Steam/Valve

This is where organizations like The Criterion Collection and Kino Lorber play invaluable services in making these films available in good prints on DVD. If only Hollywood was more eager to follow their example.