On the Virtue of Lying (Or: Go to Hell, Superman)

The truth was something I aspired to in my life and writing…until I discovered it can sometimes cause far more damage than a lie

NOVEMBER 2016. The lights are comfortably dim inside the rehab center room where my mother is supposed to be convalescing, but the reality is she’ll be dead within a month. There’s an eerie calm to the scene, her quiet snoring — on the verge of wheezing — and the tap-tap-tapping of my fingers across my laptop’s keyboard are the only sounds since I turned down the 24-hours-a-day Hallmark Christmas movie marathon playing on the wall-mounted TV behind me.

“What are you working on?” she asks me, her voice a mix of the Australian accent of her childhood and the nasally Midwestern twang she picked up over the more than four decades she has spent living in Michigan. She’s woke up, but she looks dazed; she’s not getting enough oxygen I will later learn.

My first instinct is to say something like, “Nothing, just notes,” because some part of me has never been comfortable telling her too much about my creative life. I don’t understand why this is, and maybe I never will; looking back, I know it would’ve helped us grow closer.

But I surprise myself, and instead say, “An action script I was hired to write for a director.”

“Do I know who he is?”

“I doubt it. He’s South Korean. But he’s a kind of a big deal in world cinema.”

“You know how proud I am of you, don’t you?”

“That’s never something I have to wonder about, Mom.”

She grows quiet again. I wait. Then, my mother brings up the book she’s been trying to write for years. Autobiographical, but fiction, I can never tell. She writes endless poetry, a desperate attempt to exorcise all the pain and sadness and confusion about her life and what the world has turned into.

“Will you finish it for me when I’m gone?” she asks.

“Lois?”

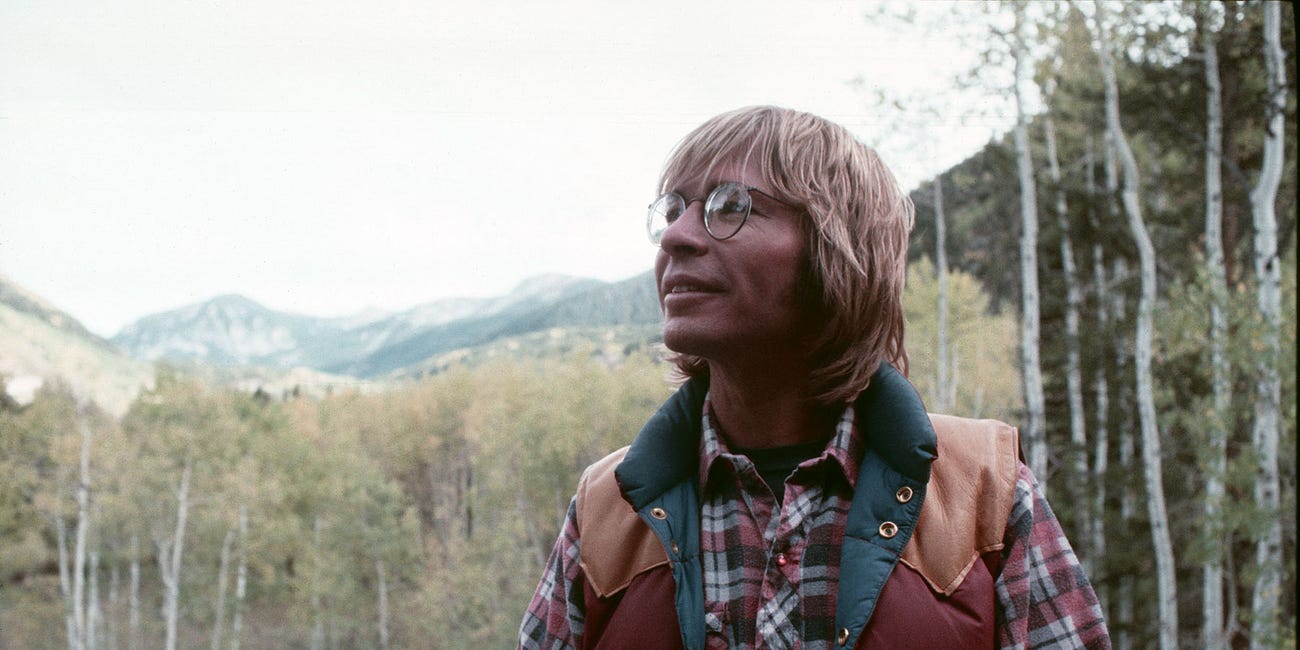

Superman, played by Christopher Reeve, is standing on Margot Kidder’s balcony. Or rather, Lois Lane’s Metropolis balcony.

She looks up at him. “Hm?”

“I never lie,” he assures her, his earnestness tempered by godly strength.

Superman: The Movie (1978) will imprint itself on me, more and more with every viewing of my childhood. And there are many.

“Mom, I wouldn’t even know where to start.”

“I can tell you where the papers are, what I’ve already written,” she tells me.

“We’re two very different writers.”

“I know you could do it,” she tells me.

“I just…I don’t know how to say I’m going to do that. I’m sorry.”

“I don’t want it all to be for nothing,” she tells me.

“I know, Mom.”

DECEMBER 2011. I’m at the gym, speed-walking on the treadmill. On the iPad in front of me is Sam Harris’s new non-fiction book Lying, really a long-form essay from the philosopher and neuroscientist. He’s making the argument that lying in all its forms hurts all relationships, whether interpersonal or societal.

What could be wrong with truly “white” lies? First, they are still lies. And in telling them, we incur all the problems of being less than straightforward in our dealings with other people. Sincerity, authenticity, integrity, mutual understanding — these and other sources of moral wealth are destroyed the moment we deliberately misrepresent our beliefs, whether or not our lies are ever discovered.

Every word of this resonates with what I was taught as a child by in Sunday School, by the chivalric code of old, by Superman most of all. Lying was something that weakened the moral character.

“I don’t want it all to be for nothing.”

SUMMER 1983. My friends and I lean over the pile of broken concrete, peering into a tiny unnatural borough where we have safely stashed it.

The bunny rabbit’s pink-red eyes blink at our curious faces.

Later, my father will discover we stole our neighbor’s pet rabbit from its outdoor cage and imprisoned it in the remains of a jackhammered-to-pieces driveway. The other children scatter, making for the safety of their own homes. My fate is less fortunate than theirs.

“Whose idea was it?” my father asks, towering over me so that I understand the implicit threat of his size. He is a veteran of two tours in Vietnam. Even at seven years old, I understand he has done things, things that seem to always exist just below the surface of his face, in his eyes, in the noises he makes in his sleep. My father is my greatest guardian, but I am frightened of him.

“I didn’t help them do it,” I insist. “I went next door, and it was already there. I swear!”

My father knows better. He can see a cowardly collaborator standing in front of him.

I’m led to the door of the rabbit’s owner, where my father returns the rabbit to its owner who had no idea it was even missing. My father then glares at me. Waiting. I shrink, embarrassed by what I’m expected to do. His eyes harden.

“I’m sorry for taking your bunny, ma’am,” I say. It’s the first honest thing I’ve said in his presence since he came home from work.

All my mother wants me to do is validate her writing as important to me, but it’s not. In time, it will become so, but in her presence, I am, for all intents and purposes, an emotionally petulant teenager again. I love her, I love her so much I can grow nauseous when I imagine my world without her, but there is a divide between us that neither of us have ever been able to find a way to bridge. It often feels as if we’re shouting at each other from across the Grand Canyon, unable to understand what the other is saying at such a profound distance.

“Will you finish it when I’m gone?”

What I later realize she’s really saying is, “Tell me I’ll be remembered when I’m gone.” But that’s being more generous to me than I probably deserve, because I think I knew then what she was really saying, too. I was terrified of her dying, and I didn’t want to acknowledge what was happening.

“While we imagine that we tell certain lies out of compassion for others, it is rarely difficult to spot the damage we do in the process,” Sam Harris continues.

“Tell me I’ll be remembered when I’m gone.”

“I never lie.”

“I’m sorry, Mom,” I say.

Her face changes, trying to hide the crushing disappointment welling up inside her.

I will remember this moment for the rest of my life. I will carry it with me through every interaction with someone I love again.

Sam Harris is right, I’m sure of it as I read. Lying has always filled me with repugnance. A Boy Scout, I’ve been called. Lois Lane called Superman the same thing. What’s wrong with that?

“There are many reasons to believe that lying is precisely the sort of behavior we need to outgrow in order to build a better world.”

DECEMBER 2016. It’s the morning of my mother’s funeral. I’m expected to speak, to deliver some kind of eulogy, but a sibling has turned on me because of a Facebook post from me announcing my mother’s death earlier in the month. I spoke honestly about the trauma of my mother’s childhood, the mythology of stories she built up around our family so that truth often seemed to change like holograms, and the eventual dissolution of her marriage to my father after thirty years. But I also spoke of the love that she transformed her children’s lives with, the tremendous effort she went to as a parent to correct the sins of her own. She was triumphant in this regard.

My sibling accuses me of truth-telling where truth was not required.

In my confusion, I turn to my father. Our relationship is no less complicated than the one I had with my mother — in so many ways, our view of the world and human beings is diametrically opposed, in fact — but at times such as these I find his moral compass always points north.

My father tells me he didn’t disagree with anything I wrote and, if that’s what I want to say to honor my mother, then I should say it and he will stand by me.

And so, I speak the truth.

Superman: The Movie was greenlit during a transitional moment in Hollywood, when the violent and ugly reality of the Sixties and Seventies, which had come to dominate U.S. cinema, was on its way out. Consequently, the superhero’s unadulterated decency felt like a rallying cry against the darkness and cynicism that had preceded his big-screen return.

“I’m here to fight for truth, and justice, and the American way,” Superman unequivocally informs Lois in it.

“You’re gonna end up fighting every elected official in this country!” she laughs, unable to take the overgrown Boy Scout’s conviction seriously.

Superman and his alter-ego Clark Kent’s honesty felt anachronistic at the time. It still does. Because it’s bullshit, a fantasy, a comic-book fiction just like the Last Son of Krypton.

JANUARY 2021. I have raced across the world, from London to Atlanta to Detroit, to make it to my father’s side before he dies. Every time the plane lands somewhere, I assume I’ll turn on my phone to news that he’s gone. But somehow I make it, bursting into my father’s bedroom and literally diving into the bed beside his frail, failing body. He’s conscious for two more hours. We take swigs of whiskey together, I kiss his forehead and cheek, I tell him how much I love him. In between all this, he beckons me close so he can say something into my ear:

“Don’t write about me.”

I look at him, because I realize in that instant that my eulogy for my mother was too much for him. The truth scares him because his past scares him. Me, being a writer, puts that past at risk of not dying with him.

“Don’t write about me, son,” he repeats, his glassy eyes locking on me.

“I never lie.”

“I promise, Dad,” I say, squeezing his hand. “I promise.”

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Absolutely wonderful, Cole. Swigs of whiskey with your father on his deathbed. A truly human moment. Wise, you are, for maximizing that moment in time.

Well said