It is December 2020, and Boris Johnson is breaking it to the United Kingdom, where I live, that he is locking the country down yet again. It hasn’t even been three weeks since he lifted the last lockdown. I feel like I’m trapped in Groundhog Day, and the British prime minister has come to represent the vague existential threat that once forced Bill Murray to endlessly repeat the same day, over and over and over, until he got his shit together. This precipitates yet another phone call to my father in the United States, my only surviving parent, to tell him my family still can’t make plans to visit him for the foreseeable future. “It’s for your own good,” I assure him, given that he received a double lung transplant two years earlier and, consequently, has a nearly 100% chance of dying if he contracts Covid-19 from me, my wife, or two children. He agrees with me, or at least he claims to, but I know he is lying. He wants to hold his “grandbabies,” as he calls them, Anthony Fauci and his scientific reason be damned.

It is 2014, and I am holding my new son for the first time in a Downtown Los Angeles hospital. He is so large that the doctor gasped when she first set eyes upon him. I marvel at the heft of him in my arms as I hold him against my bare chest and assure him, “I’m your daddy, I’m your daddy, I’m your daddy.” My wife is on the operating table behind me, still too drugged up to hold him. I feel as if I’ve stolen something from her because I wasn’t supposed to be the first one of us to touch our son.

It is 2008, and my mother is playing with my hair as I sit on the floor beside the recliner where she spends more and more of her time since she divorced my father. We do not touch anymore except to hug hello and goodbye, though I cannot explain why, and this once ubiquitous gesture in my life — now excruciatingly alien — makes me feel both confused and uncomfortable. Nevertheless, I do not tell her to stop, and for the duration of the film we are watching, one of our favorite things to do together, I am a child again.

It is 2016, and I am having lunch with a friend. He tells me that his teenaged sons still lie on the sofa with him, his arms around them as they watch films together. I can’t even begin to imagine doing something like this with my own father, and I don’t think my friend understands how confusing this is to me or how worried I am I will not be able to say the same when my children become teenagers.

It is February 2020, less than a month before Boris Johnson will announce the U.K.’s first lockdown, and I am in Los Angeles for work. Every time I come to town, I assemble a large crowd of my favorite people — most of them screenwriters, producers, and actors — for drinks. The news is already hinting at what’s to come for all of us, but everyone here tonight is pretending that they’re not in the first act of a horror film. We hug each other, we eat from each other’s plates, we touch without any real sense of how impossible this will all feel soon. In three days, I will board a plane back home, already scrubbing down every surface around me with antiseptic wipes before I dare come into contact with them.

It is 2007, and I am delivering an eulogy for my grandmother — my Nana as I called her — and I begin to break down before the witnesses to her life gathered today to mourn her death. My father, a large man, much larger than my 6’1,” rushes to my side and wraps his arm around me to help me keep it together. It is as jarring to me as my mother touching my hair; outside of strong hugs, this reassuring touch is inexplicably verboten in our relationship. When I am finished speaking, he declares to the people who fill the pews of this rural Michigan church, “This is my son, and I’m proud of what he just said.” All of this is very strange to me.

It is 2018, and I am explaining to my eldest son, now four, why we don’t visit or FaceTime with my mother, his Nana, like we do his other grandparents. It is a spontaneous dinner table decision that reveals to him that Nana died two years ago. I have put it off for so long, trying to work out the right time to do it, that I just start telling him out of fear I never will if I don’t right then and there. My son is silent for a long moment, probably because his father is crying in front of him for the first time. Then, he jumps to his feet, runs around the table, and throws his arms around me to try to make it better. It almost does.

It is September 2020, and I am in London for the first time since the pandemic triggered the U.K.’s first lockdown. Almost 42,000 Britons have already died from Covid and almost one million people worldwide; most of these people did so alone or cut off from their loved ones’ embraces. A screenwriter friend and I have spent the past four hours strolling through Notting Hill together, bemoaning how much we’ve missed physical contact while reminding ourselves about how strict we must be about social distancing. As we say goodbye, I tell her to put on her mask. We wrap our arms around each other, our chins shoved into opposite shoulders so our mouths are as far away from the other’s as possible. It’s the first time I’ve touched anyone besides my family in six months, and I have tears in my eyes.

It is 2011, and I am looking for an excuse to hold my mother’s hand as I now do during my yearly visits to my hometown in Michigan. I attempt to pretend like this isn’t awkward because I don’t want it to be anymore, but it is, at least for me. It isn’t for her. I wonder when my mother’s baby stopped holding her hand and how much the loss of my touch has tortured her over the years.

It is 2016, and I am huddled with my sister and brother-in-law three hours before the flight on which I am meant to return home to see my mother before she dies. My cell phone rings. It’s my brother, who tells me “she’s gone” even though the doctors assured us she’d last at least a few more days. I go to my sister, who is in a wheelchair, and kneel beside her so that we can hold each other because our mother is dead. All I wanted was to hold her hand one more time.

It is January 29, 2021, and I am running between airport gates to catch a connection between Atlanta and Detroit. I have raced from the U.K. to the U.S. in the midst of a pandemic because my father is about to die from complications from organ rejection (rather than Covid, which I have assumed for a year now would be his doom). Every leg of the journey has begun and ended with panicked phone calls to family members to ask, “Is he still there?” I choke on tears every time I utter this question, and every time — so far — I have heard some variety of, “Yeah, but I don’t know for how much longer. You have to hurry,” in ominous reply. “Tell him I’m coming,” I say, “tell him I’m coming.” I am terrified that I will miss him, as I did my mother. I need to hold his hand one more time.

It is 1997, and I am saying goodbye to my parents right before I climb into my car and drive cross-country to move to California. It’s my first time hugging them like this right before similarly long departures from my childhood home. From this moment on, every time I repeat this farewell, it will be fraught with danger, the very real risk that this will be the last time I see them alive, that this hug will be the last time we even hold each other and tell each other, “I love you. I love you, too. I’ll see you soon.”

It is January 30, 2021, and my father is dying slowly beside me. He drifted asleep not long ago. My brother attempts to play Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” which is one of our father’s favorite songs, but he accidentally plays a Greek cover of it instead; it reaches the first chorus before the hilarious mistake is even noticed in the mournful gloom. We all laugh at this soundtrack error. Since I arrived three hours ago, I have not left my father’s side; I have held his hand as I hoped to and rubbed his too-thin arm, I have stroked his forehead and sweaty, thin hair, I have run my fingers over the coarse beard he grew after losing the ability to shave. It’s been more than a year since the last time I was able to touch him at all, and the irony that it’s only now that I am able to do it again, as he fades away for good, feels sick and cruel.

It is 2016, and I am walking out of my mother’s room at the rehabilitation center where she is recovering from a slew of ailments that have attacked her body with increasingly malicious frequency. I go back to her and put my arms around her a second time. I don’t want to let go of her. I know this is the last time that I’m ever going to see her, even though I tell myself it isn’t so I can muster the courage to walk out the door. I say goodbye, and then walk out the door.

It is January 31, 2021, and I am holding my father’s hand as he dies on a Sunday morning. I do not want to let go even after I realize his hand is becoming cooler to the touch. It is remarkable how quickly the body’s heat begins to dissipate once the heart stops pumping fresh blood through it. I kiss his forehead, whisper goodbye in his ear in case he’s still in there somewhere, and I walk out yet another door.

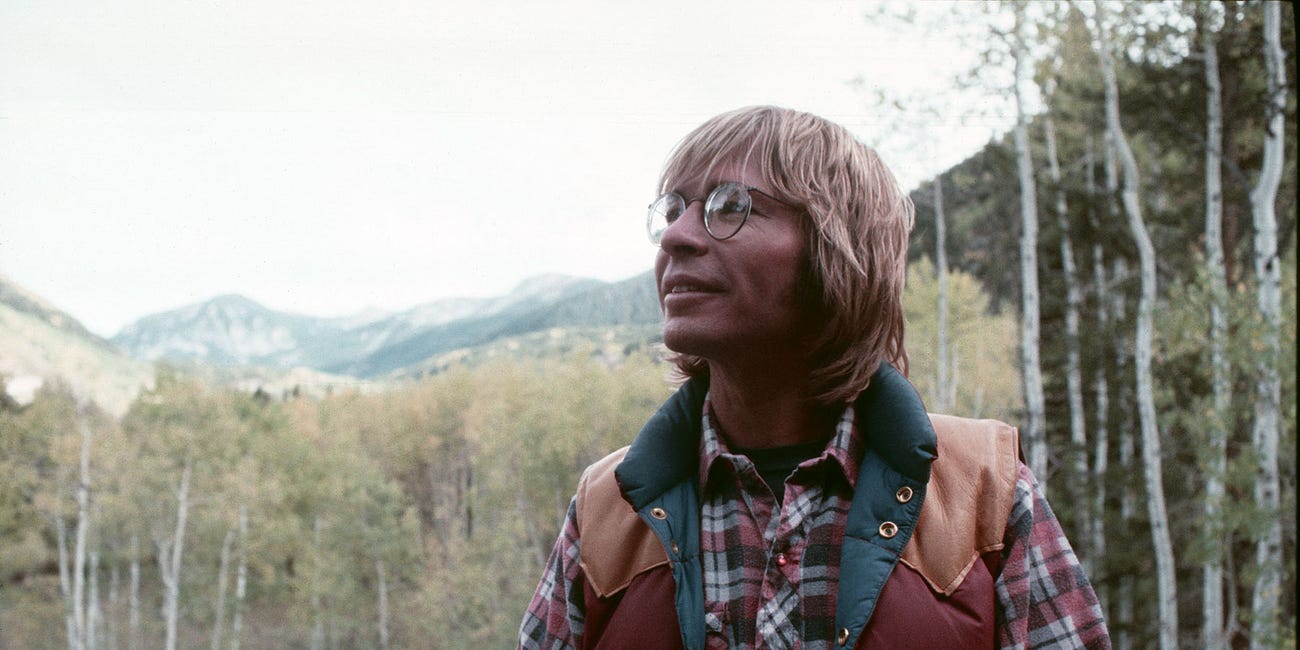

It is now, and my son and I are lying on the couch, watching a classic adventure film together. This is a rare treat for him, as this means he has been allowed to stay up long past his bedtime. He is ten, and I am running my fingers through his honey-colored hair as I have a thousand times before. It’s a simple, but transportive act that carries me both backwards and forward in time to moments I cannot get back and others I’ll one day be able to say the same about. When I stop, he nudges his head against my ribs as a way to ask for more.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Oh Cole, I really loved this. You made me tear up, and want to rush over to my parent’s house and hug them, and go and see my sisters and my brother and, we’ll, everyone important to me. Thank you for this wonderful gift. You are an incredible writer. 🙏❤️

Oh, man. So lovely. Many tears.