How to Write a Killer Opening to Your Screenplay: 'Scream'

Kevin Williamson's horror script is a master class in how to keep your readers turning the page (while also scaring the sh*t out of them)

I’m a pretty firm believer that the only unbreakable “rule” in feature screenwriting is “make the reader keep turning the page.” That’s it, really. Whether it’s an agent, a producer, studio executive, an actor, a director – it all comes down to the same thing. Make them keep turning the page.

That said, if you aspire to write a screenplay that makes a splash in Hollywood, the other rule I’d suggest you follow – let’s call it guidance (because rules don’t really exist in art) – would be “grab them with a killer opening.” Specifically, a teaser that hooks the reader on Page 1 and doesn’t give them a chance to second-guess the time they’re spending reading your script until the inciting incident some ten to twelve pages/minutes into the film. If you pull that off, you’ve got them hooked until the Act 1 turn – and if you then nail that plot turn, there’s a very good chance they’re going to read all the way until THE END.

So, let’s get into one way to write that killer opening – emphasis on “killer” – by taking a look at one of my favorite examples of one.

I’m talking about Scream (1996) here.

This is the script that launched screenwriter Kevin Williamson’s whole career, a career that is the dream come true of pretty much every person who’s ever said, “I’d like to write movies someday.” As I write this, his credits include eight films as screenwriter (several more as a producer) and ten television series that translate to hundreds of hours of produced work. It’s mind-boggling how prolific and successful he’s managed to be…but when you read Scream’s script, you quickly begin to understand why.

Scream is also a film that, in many ways, reinvented and reinvigorated the horror genre in the ’90s. It was so successful, in fact, its sixth sequel will be released next year – 29 years after the original was. But I would argue none of that would’ve happened had the opening sequence I’m about to break down — the vicious murder of CASEY BECKER (Drew Barrymore) — wasn’t so effective both on the page and screen.

On screen this sequence plays out over 12 minutes and 52 seconds – a typical length for a grabby opener like this. But in the screenplay I’ll be referencing, dated July 31st, 1995, it’s 17.5 pages long.

This wild discrepancy between script and screen is somewhat unusual, in that pages tend to signify minutes; one page equals one minute of screen time. You might wonder why this difference exists. A casual assumption might be that Williamson overwrote it on the page, bloating the page count as less-experienced screenwriters tend to do, and director Wes Craven had to hack all that fat out during later development or in the editing room once the sequence was shot. But you would be wrong about that.

The 17.5 pages Williamson wrote are realized onscreen with almost no alterations to dialogue or action (which is a kind of Hollywood miracle, by the way). When dialogue does change at all here, it’s only because Barrymore probably found a more “her” way to say something as she tried different takes. The action is almost perfectly transposed to the screen, too.

No, the real explanation for the discrepancy here is the approach to the now-famous conversation between the Becker character and the voice on the other end of the telephone.

You’ll notice at the bottom of Page 3, Williamson describes the voice – identified as THE MAN – as “flirting with [Becker]”. This is key to understanding the first two acts of this sequence. It’s written as a seduction, or at least it starts that way. Specifically, in the tennis match style of romantic screwball comedies. Cary Grant serves, Irene Dunne returns, back and forth, each subsequent return creating greater and greater sexual tension until boom. What this means in practice is a lot of single lines of dialogue, a lot more than in a normal script, which adds up to those extra four pages to the script’s opening sequence.

You might’ve noticed I just said there were multiple acts to this sequence. Whether Williamson was conscious of it or not, Scream’s opening sequence works so well because it’s constructed like a three-act story complete with most of the cinematic turns we’re all accustomed to from Hollywood films. This is not necessary for every scene, of course, but the more I’ve studied great films and their screenplays over the years, the more I’ve recognized that we constantly reference ones that do. Because of this, I’m going to share the sequence in script format according to the acts I see, with clear explanations of its major turns, which I’ve never done before at 5AM StoryTalk.

As you read, I want you to track how each act also entirely changes the sequence’s identity, ratcheting up the stakes: romantic comedy > thriller > slasher flick. In each act, try to “feel” how the tension is building toward some kind of release — the act turns — each increasingly violent. How did Williamson accomplish this on the page? This will help you try to do the same with your own work. Along the way, I’ll flag other important elements of the script that helped grab readers and, eventually, studios that engaged in a bidding war to purchase it.

Let’s dig in together now…

THE MURDER OF CASEY BECKER — ACT 1

What I love there is how the end of the first page is the first act’s INCITING INCIDENT. Not the first phone call, but the second one that signals to audiences there’s something amiss here. Rarely do pages end so perfectly, especially first pages, creating a need in the reader to find out what the next sentence is going to be. “Oh shit, the guy called back. What happens next?! Guess I’ll turn the page…”

Note the description “affluent”, too. This isn’t a throwaway detail. Bad things don’t happen to affluent people in our cultural consciousness. And they certainly don’t happen to cute blonde girls like Drew Barrymore — we’re talking Gertie from E.T., after all.

This is an obvious bit of stunt casting similar to Alfred Hitchcock casting Janet Leigh as the lead of Psycho (1960) only to kill her at the Act 1 turn. Nobody saw something like that coming, just like nobody expected Wes Craven to cast a name like Barrymore, a beloved former child actor, and then whack her off thirteen minutes into his film. In doing so, Williamson and Craven were announcing all bets were off. Everyone can die in this story, even your biggest star.

The phone has just rung a third time, and Casey has answered it. There’s a playfulness to what’s happening on the page so far. In some other film, this might lead to a romantic comedy. But still, there’s a nagging feeling something is wrong. Please, Mr. Williamson, tell me what happens next…

“He’s flirting with her”, like I said…but I’ll add, the flirtation has led to films and, in particular, “scary movies” coming up. This will be relevant in a moment.

You might appreciate that Craven kept this jab at the sequels to his film Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). His original was scary, “but the rest sucked”. But the reference is more significant than a director expressing some bitterness over how New Line cashed in on his work with inferior knock-offs. By including it, Scream establishes two things:

All the horror films that preceded it exist in the same universe, meaning all the people in it have a relationship to slasher films directed by people like Craven. This means the rules of this universe are different than all those other flicks, which makes everything that follows immediately more unpredictable. A reader in the mid-90s would’ve had their minds blown by this.

Craven including this in-joke in the film itself is telling audiences who are familiar with his contributions to the genre that there’s a deeper meta-conversation going on here. The audience immediately becomes a deeper, more active participant in the story taking place on screen because, in some way, Craven is now speaking directly to them.

And there it is, our ACT 1 TURN. The rom-com has turned into a thriller. The reader is on Page 5, and they are hooked hard now. Weird tension has become high tension. Something bad is about to happen…what?! Well, turn the page and find out.

THE MURDER OF CASEY BECKER — ACT 2

We’ve reached Act 2, where the real drama of the this three-act story is going to play out. What I mean is, we know the engine behind the plot now. Casey Becker has been targeted in some way and is now in terrible danger. What’s going to happen to her? Will she survive?!

Midway through this last page, shit just got real for Casey. For a moment there, she thought she was just being messed with by a creep, but that threat, especially the delivery of it onscreen, changes everything.

It’s followed by a very important line of dialogue: “More like a game, really.” While it might sound like a fun toss-away line, it builds on the earlier references to existing scary movies. The killer — whom we’ll eventually identify as Ghostface in pop-culture — is a horror film expert and is using his knowledge of the genre to toy with Casey as he will toy with later victims.

What Williamson is really doing here is announcing how his script is going to also toy with readers and audiences. Again, it’s hard to stop turning the page of a script — or stop watching a film — you’re an active participant in.

More scary movie rules. “You should never say ‘Who’s there?’ Don’t you watch scary movies? It’s a death wish.”

Uh-oh, Steve is fucked.

Again with the games talk. I still remember how terrifying it was seeing all this play out on screen for the first time. I was only twenty, and this whole sequence evoked every lonely night at home I’d ever spent, wondering what those noises were outside. What if someone had tried to terrorize me in the same manner? It certainly wouldn’t have been difficult.

Pay attention to how this tension is being drawn out. Like a rubber band being pulled tighter and tighter. You know it’s going to eventually snap, but you don’t know when. You’re left bracing yourself — an emotional reaction you should want to elicit from your own readers.

This trick is cruel, but also an incredibly rewarding one for horror film fans. Most people who would’ve been sent Williamson’s Scream script would’ve been genre-friendly readers. Friday the 13th wouldn’t have even been fifteen years old at that point. What I mean is, the people making professional decisions here would’ve known the answer to this question right away and would’ve known Casey had fucked up before even she did. That small window of time, where they’re waiting gleefully to find out what happens next, is a special kind of drug in cinema. Again, this is how you get readers to keep turning the page.

Steve’s gory death is Casey’s LOW POINT, to continue to track this three-act story.

Note the word “incite” here, but also “springs to her feet”. That’s another way of saying, “Casey has decided to act.” This is our ACT 3 TURN.

THE MURDER OF CASEY BECKER — ACT 3

If Act 1 was a rom com and Act 2 a thriller, Act 3 becomes a full-fledged slasher flick.

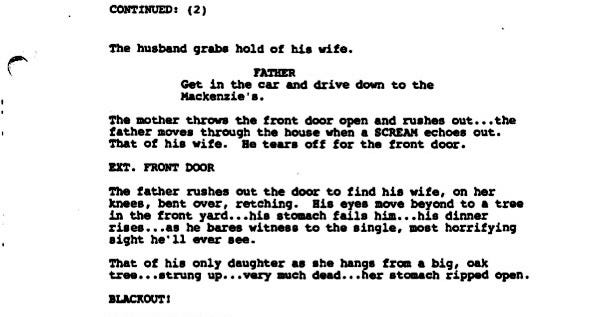

Two things happen on this last page that I feel are important to note.

Ghostface is revealed. “Ghostly white mask”; that’s all readers got at the time. I point this out because it was largely left to their imaginations, which means they could conjure whatever horrifying mask they wanted to.

A potential way out of this nightmare appears in Casey’s story when her parents’ headlights approach, which creates another question for readers: Is this how Casey will be saved? Questions that you make your reader desperate for answers to means they’ll keep reading.

At first, you might question the sudden introduction of new characters into this sequence. Her parents take up a lot of real estate on the page. I think that might be true in most cases, but the payoff here, which is fast approaching, is just too good to not properly set up.

SHE CAN HEAR HER DAUGHTER DYING!

Holy fuck, brutal. Just brutal. There are so many things I love about Scream’s opening, but this is the one that takes it to a whole other level for me. There’s a cruelty here, born from Williamson’s imagination, that is terrifying in a way organs spilling out of a body could never be.

I’ve read this script several times since the early 2000s. There is so much to love about it in its entirety, but this sequence — culminating with this final, devastating block of description — trumps everything that follows except for the finale. That’s what makes it such a killer opening. Once you read it, you can’t imagine stopping. You need to find out how the whole story ends. And in the case of Scream, because the script ultimately sticks the landing in a big way, executives marched it into their boss’s offices and said, “I think our found our next big movie!”

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

God, I love this film! Genuinely one of the most memorable openings ever.

I remember watching this when it first came out and my boyfriend and I nodding knowingly at the mention of Friday the 13th, knowing that Craven had directed it, and this was dissing the sequels. It was one of the first times I remember getting a reference like that.💕 we felt like we were part of a club.

Fantastic analysis and article, Cole. Thank you so much.