How to World-Build Like a Wachowski

The first eight pages of 'The Matrix' (1999) script provide a MasterClass on how to introduce a complicated world

World-building is the bane of every ambitious screenwriter’s life, because so much of genre storytelling requires it and yet most of us lack the skills to do it well. To make matters worse, if you’re working with producers or a studio, network, etcetera, you must also contend with notes constantly pleading for you to clarify rules. These notes, more often than not, presume the audience is comprised of idiots.

Fortunately, there are many excellent examples of complicated world-building economically introduced onscreen without the benefit of narration or opening text — and maybe none better than THE MATRIX (1999) in this regard, which is why I’m going to walk you through the first eight pages of the screenplay in this essay.

Despite the title of this essay, I won’t be telling you how to do it yourself, but rather help you see how the filmmakers did it and, in (breaking the rules and) telling you what the Matrix is, help you develop the tools to start doing it yourself.

Please note, narration and opening text setting up an alien world can work well and is, sometimes, even preferable — STAR WARS (1977) and BLADE RUNNER (1982) come to mind — but I believe it’s always wisest to start your screenplay with the ambition of doing neither unless it’s inherently baked into the concept. You can then course-correct later. One advantage of trying it this way is your audience is engaged from the first minutes of your screenplay — participating in the story, asking questions, trying to work things out — and it’s much more difficult to lose them when that’s the case.

So, let’s dive into the first eight pages of THE MATRIX, written and directed by the Wachowskis and shared with you for educational purposes. This draft is labeled the shooting script and is dated March 29, 1998.

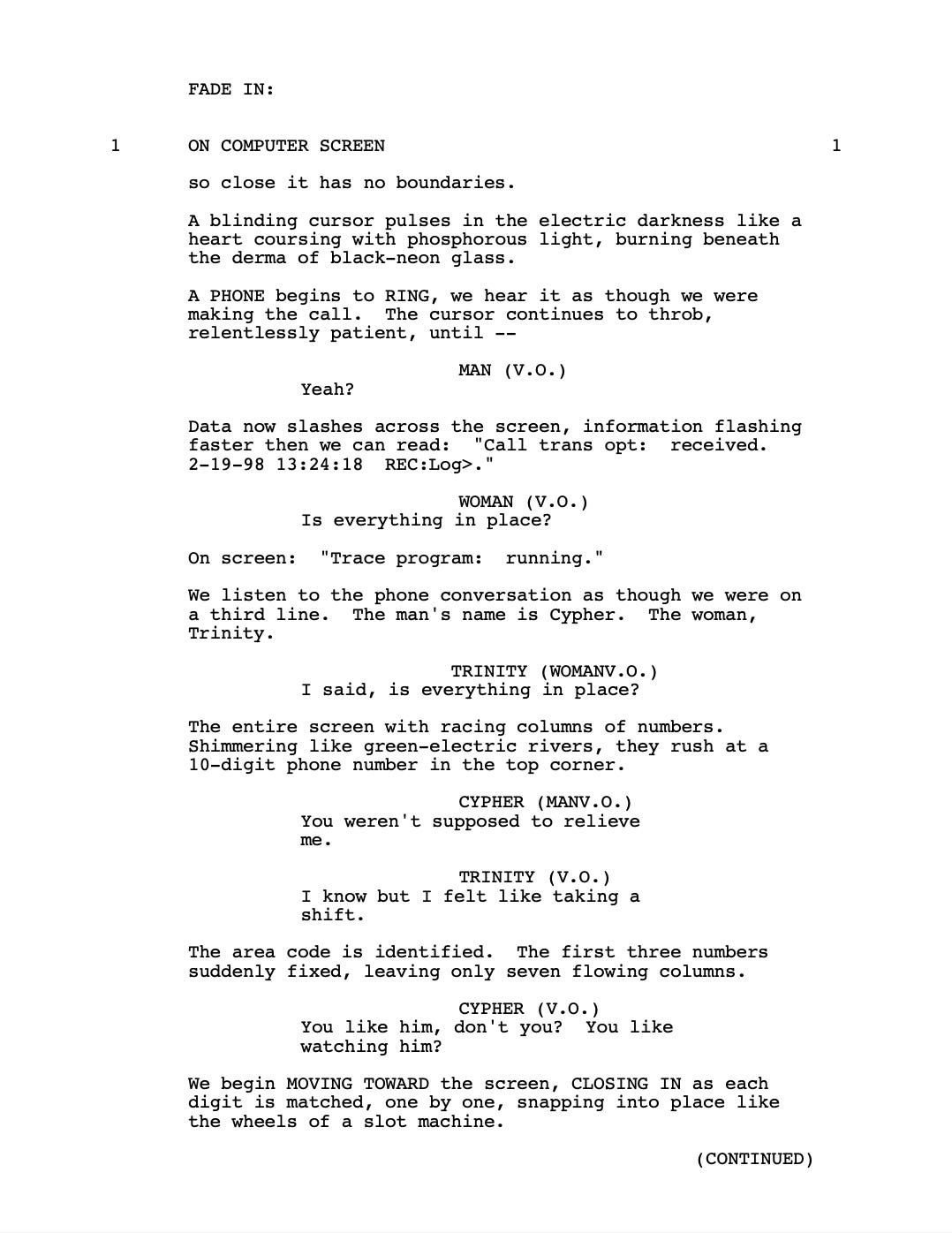

PAGE 1

As I read this page, I’m going to try to imagine I’ve been told nothing about this screenplay except its name and that it is science-fiction. I’m a Hollywood producer, trying to cram this script in between phone calls.

Okay, so there are three significant things happening on this first page as I, Mr. Producer Man, start to read — checks the cover of the script again — THE MATRIX:

The action is happening inside a computer, as near as I can tell. Since it’s probably 1997 as I read this script, the dawn of the Internet Age, something like this feels new and exciting, but also creatively interesting. It’s both servicing the plot and different. I’m hooked.

So many questions. The Wachowskis are generating one after another, and each one I want answered right away. I’m compelled to read more to find out what they are. Why am I inside a computer? What is this place? Who is the “Him” they’re watching? Come to think of it, who are the people watching the mysterious “Him”? And does Trinity like “Him” and, if so, what does that mean? Add in the extra spin that Trinity is a woman and she seems to be obsessed, maybe even stalking this man, and I am, again, hooked.

A ticking clock. “Flashing faster than we can read.” “Trace program: running.” “Racing columns.” “Rush.” A phone number being identified one digit after another. Something is happening…but what? Another question!

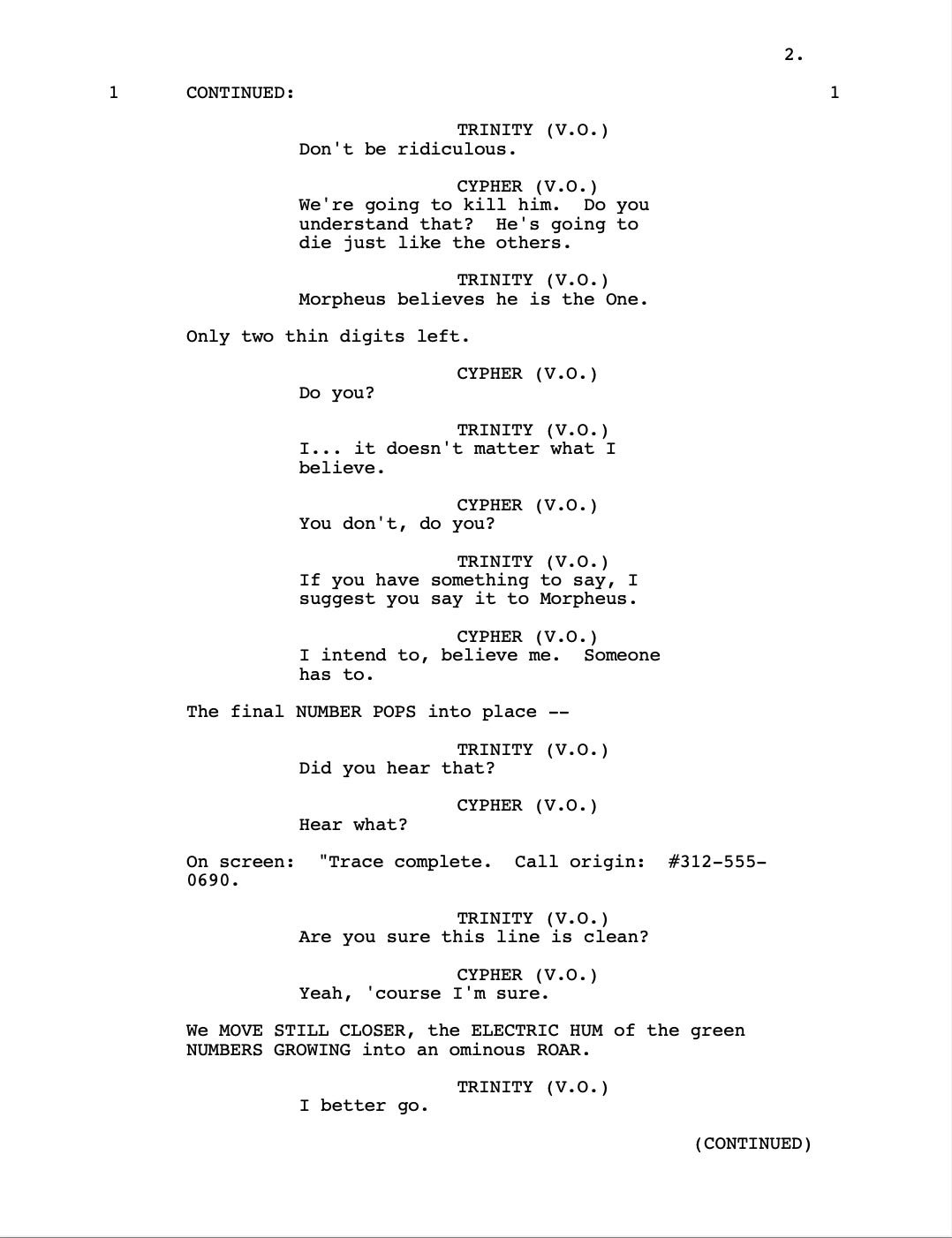

PAGE 2

I’m two pages into THE MATRIX, and the excitement level is mounting because conflict is introduced to the story.

“We’re going to kill him. Do you understand that? He’s going to die like the others.”

Trinity doesn’t argue with that. She simply says, “Morpheus believes he is the One.” That’s all she needs to say.

“Do you [believe he’s the One]?” Cypher asks.

Trinity can’t say she does, and Cypher senses it.

Conflicts established:

“Him” has a mark on his head. That doesn’t sound good.

Morpheus believes he’s the One, which means Morpheus will oppose killing him “like the others.”

Trinity also doesn’t believe he’s the One, but “likes” the man marked for death.

Trinity, Morpheus, and Cypher all have different opinions about what to do about “Him”. I can only suppose “Him” has his own opinions about whether he should live or die, too.

On top of all this: two more questions.

Who is Morpheus?

What does “the One” mean”?

All as the ticking clock continues to race, propelling us forward like the tension between Trinity and Cypher.

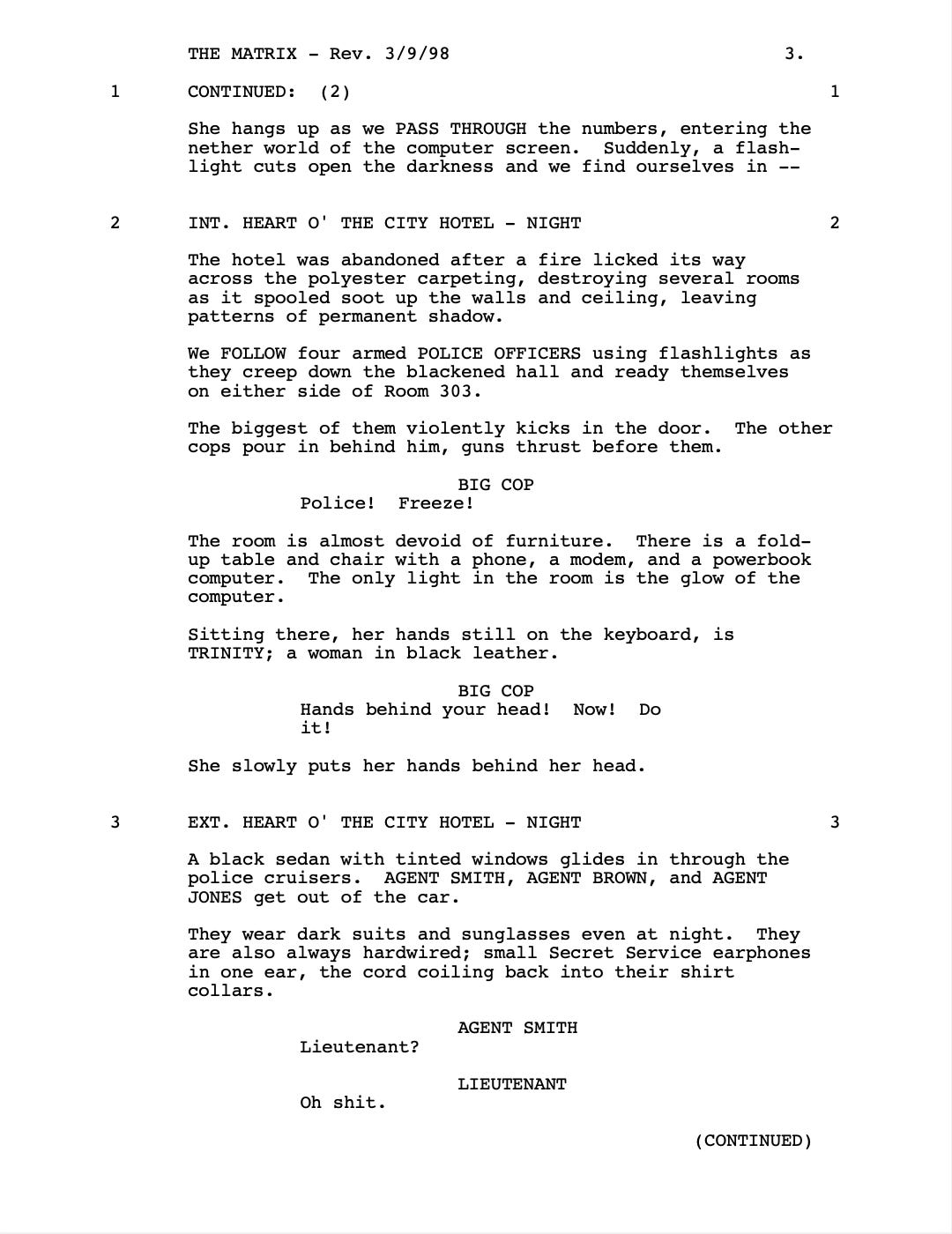

PAGE 3

Welcome to the real world rather than a digital one! Or so I think.

On this page, I suggest you look at the economy of language being used. Descriptions are doled out like shotgun blasts, no waste anywhere to be found. Commas are virtually non-existent, so no run-on sentences. A single semi-colon deftly used.

Additionally, pay attention to the verbs used and how effectively they evoke the images that ultimately show up on screen: creepy, thrust, glides.

The choice I like most is glides to discuss how the arriving car full of mysterious agents arrive. It suggests something almost supernatural.

And then there’s the woman in black leather — Trinity!

Mr. Producer Man is three pages into THE MATRIX, and a rich, complicated world, full of rules I don’t fully understand yet, has been suggested. My ignorance in this case is not the same as being confused or lost.

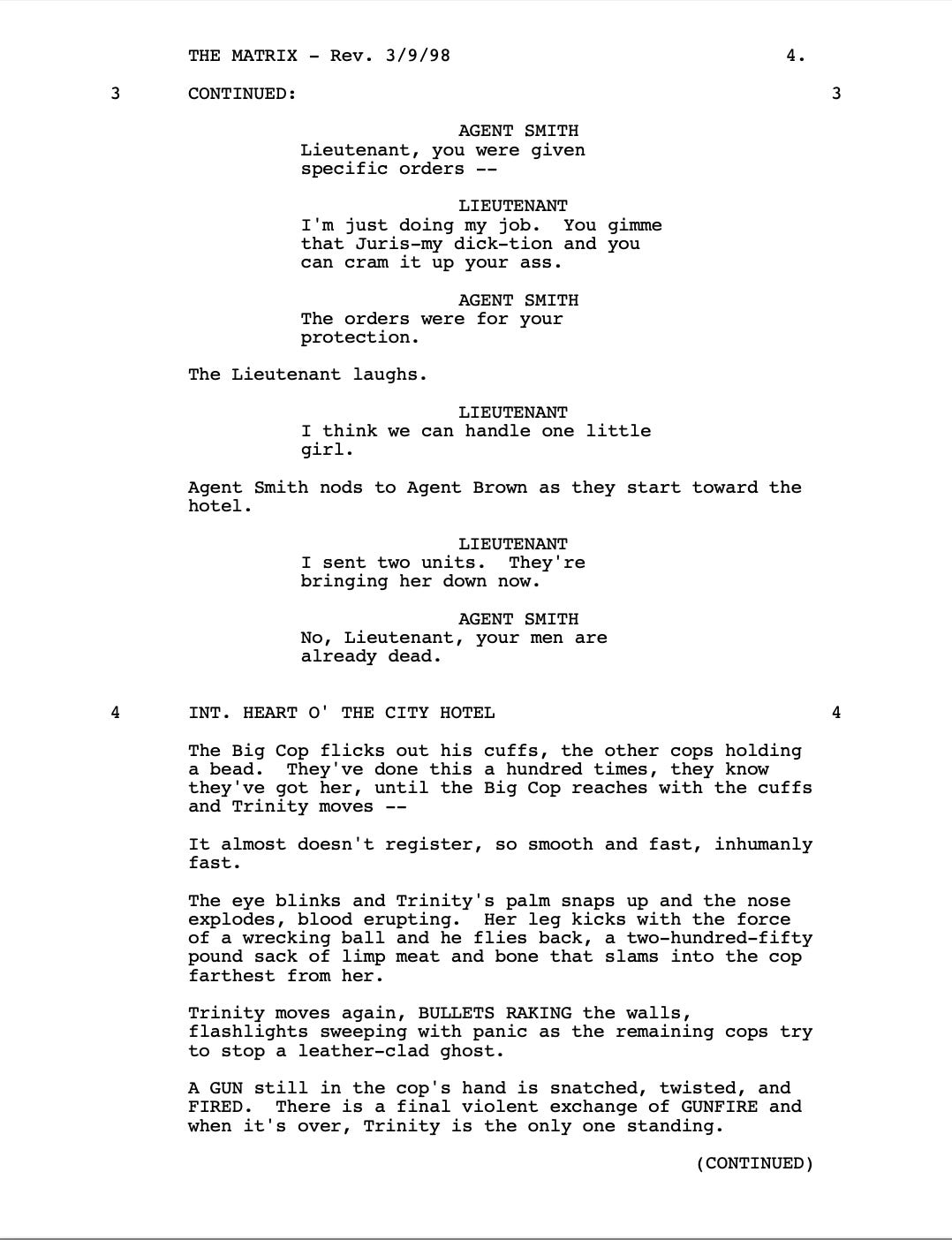

PAGE 4

This page is all set-up and pay-off, though I might argue it’s a darkly comic set-up and punchline.

The set-up:

The cops mistake Trinity for “one little girl.” “I sent two units,” their lieutenant says. “They’re bringing her down now.”

Smith, possessed of a secret knowledge, know better.

“No, Lieutenant, your men are already dead.”

The pay-off/punchline:

Trinity physically obliterates the cops’ bodies.

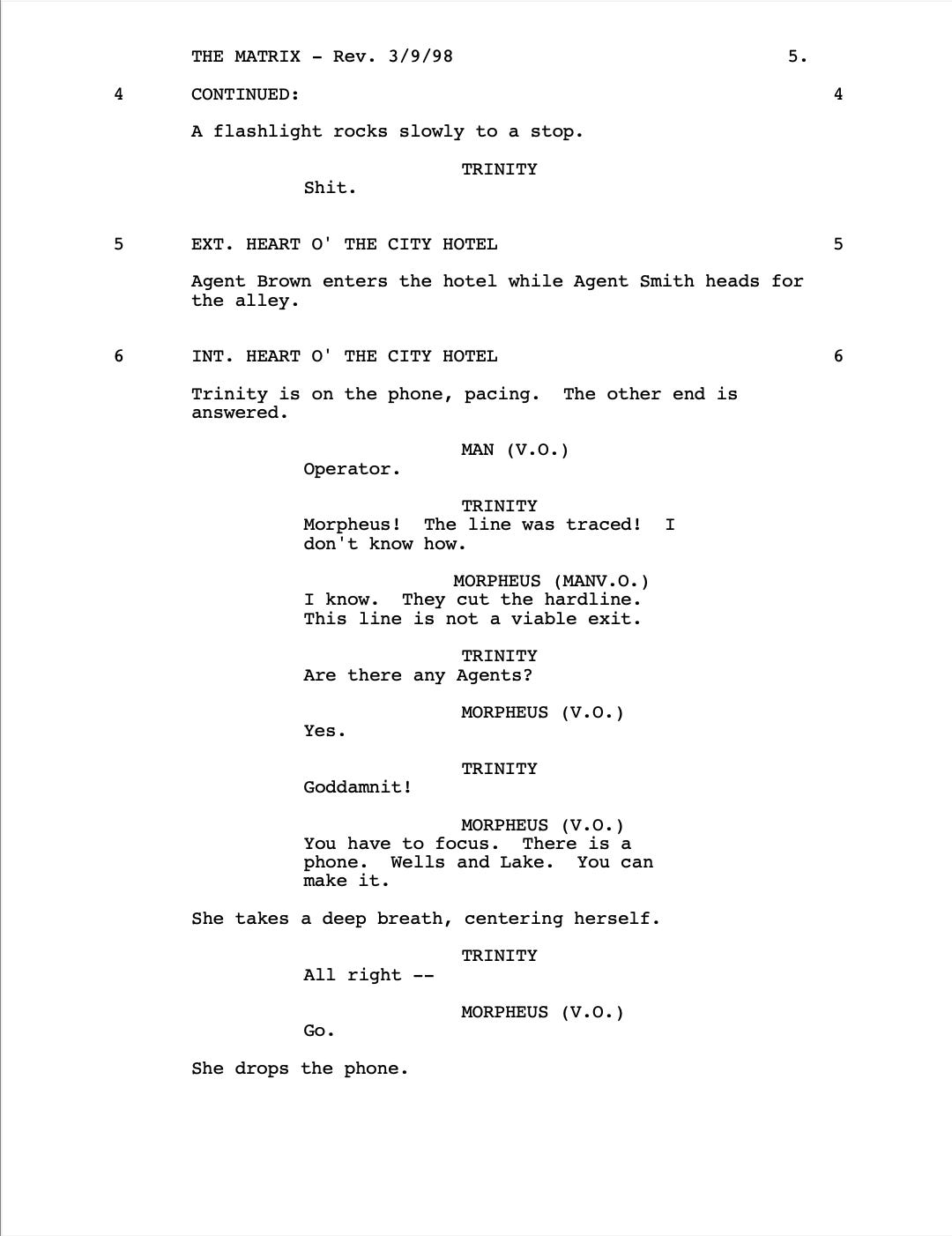

PAGE 5

“This line is not a viable exit.”

“Are there any Agents?”

“You have to focus.”

Don’t overlook the importance of each of these lines of dialogue to THE MATRIX’s story, but, equally important, its complicated mythology — another way to say world-building. As I mentioned a moment ago, ignorance is not the same as being lost.

World-building is happening all around me as I read, such as the concept of “exits” by telephone (wait, what?!), “Agents” as dangerous threats specifically hunting our heroes, and a sagacious line I will ultimately discover is inflected by Morpheus’s relationship to Eastern philosophies.

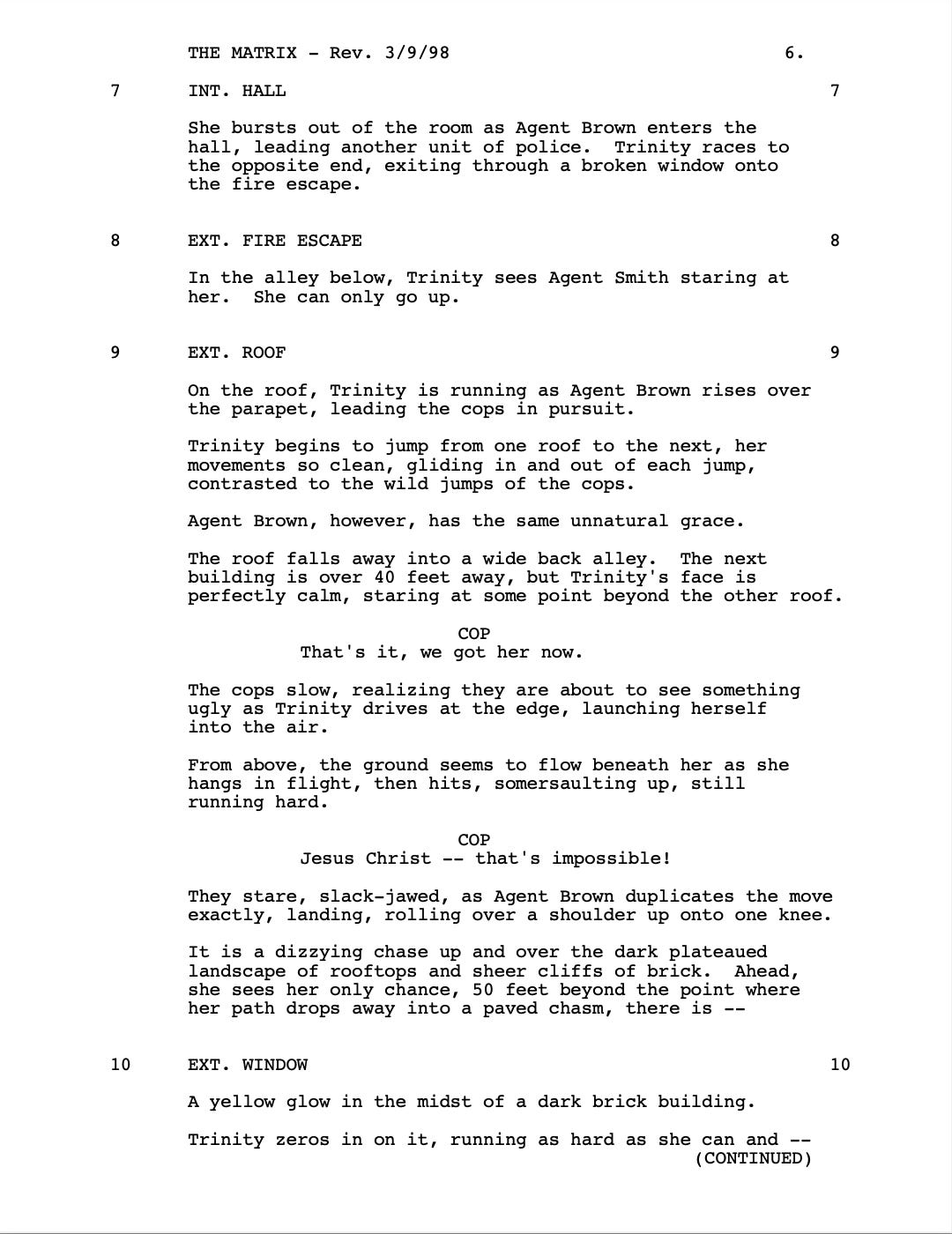

PAGE 6

“The next building is over 40 feet away.”

“From above, the ground seems to flow beneath her as she hangs in flight, then hits, somersaulting up, still running hard.”

“Jesus Christ — that’s impossible!” a cop reacts.

And then, Agent Brown does the same thing.

Translation for me, Mr. Producer Man as I read: holy shit, people in this world are like superheroes in black leather!

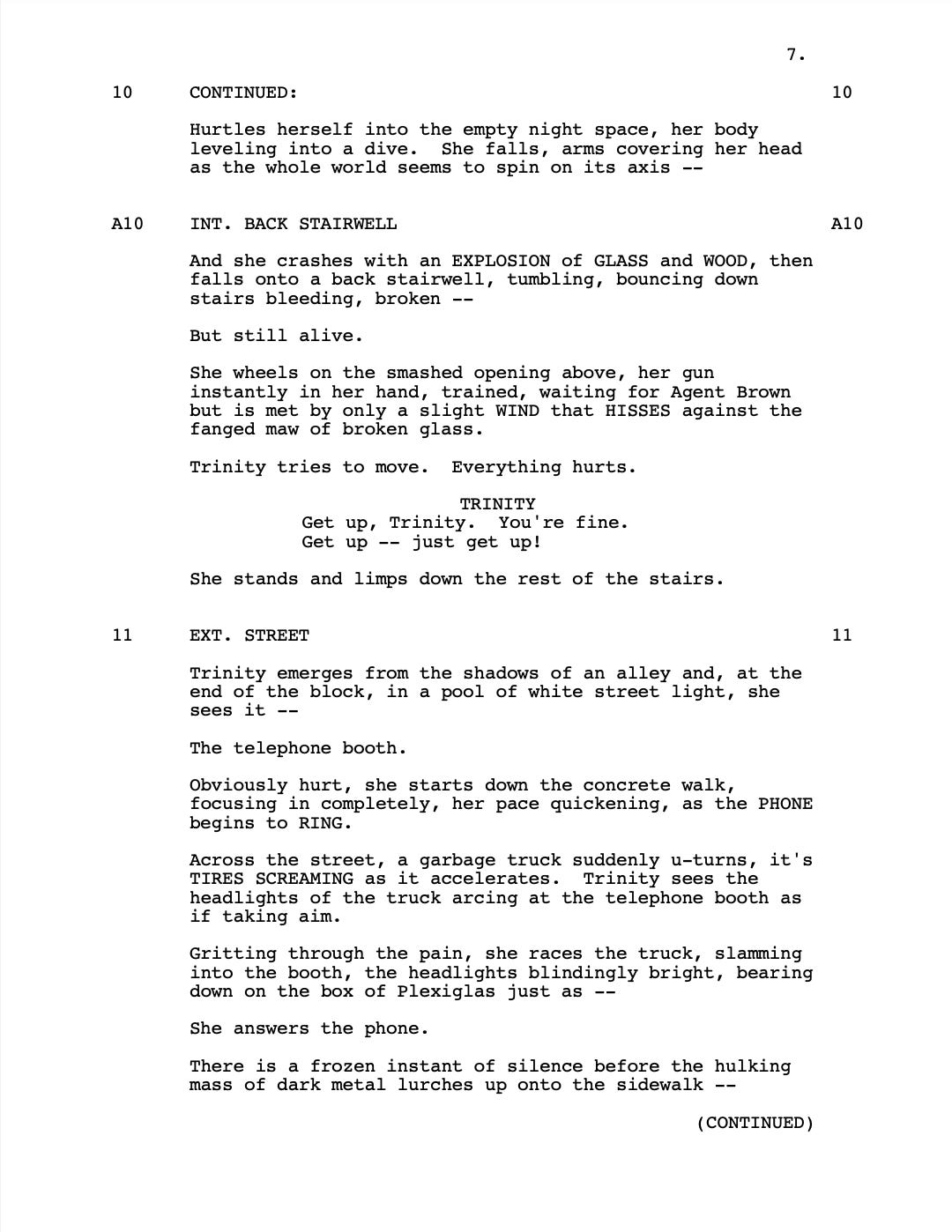

PAGE 7

I’m seven pages into THE MATRIX, and for all intents and purposes, Trinity is the film’s heroine, as near as I can tell. Think about the stakes this sets up, because Trinity, I’ll imminently discover, isn’t even the most impressive member of her team — and “the One” is going to run circles around all of them.

Oh, and there’s a telephone booth. When Morpheus advised Trinity there was a “phone”, it wasn’t cutesy code. He meant a literal phone.

Weird, right? Mr. Producer Man thinks so as I flip to the next page of THE MATRIX (remember, it’s 1997 and everyone reads scripts in printed form; I only just got my first email address, in fact).

PAGE 8

What the what the what?! Trinity disappeared, something to do with the phone…which I also know is an exit. Did she somehow travel through the phone? “She got out,” Agent Jones says. Well, well, it does appear so.

The Wachowskis have not explained to me how this works in their script, but I understand this rule already all the same: people can pass through certain phones and travel elsewhere, which, come to think of it, isn’t much different than how information in the late-nineties used phone lines to travel between computers. Ooh, intriguing.

On top of this, I’ve just discovered some important information about the world that is about to rapidly expand before my eyes:

The Agents have an informant inside Morpheus’s team.

“Him” is named Neo, and now both Morpheus and his team and the Agents are after him.

Oh, and here, I’ll spoil what Page 9 reveals right away:

Think about how much has been established by the time Neo even enters the story — Mr. Producer Man’s mind is blown!

TAKE-AWAY

A film doesn’t have to explain what everything means every time it’s introduced. You can allude, you can set up, you can lay a trail of narrative breadcrumbs to cinematic enlightenment.

Eight pages into THE MATRIX, and the Wachowskis have already established a William Gibson-esque techno-thriller tone, set up their film’s myriad conflicts, and taught me an entirely new vocabulary that they will soon use to explain their complicated world. No narrator, no lengthy text exposition before the film starts, nothing of the sort. Just clean, unbelievably brilliant storytelling that never speaks down to or remotely underestimates the audience.

If this article and the time I spent on it added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is now available from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. Paperback will hit shelves on May 25th. You can order it here no matter where you are in the world:

So helpful, thank you!

Thank you for great read! THE MATRIX was and will be always one of my favourite movies.

Couple of days I’ve read an article on Medium from a writer, who wrote how devastated he was as he tried to create a whole world. The relief came when he understood that you don’t have to explain everything to the reader. He just needs the information to understand what is really required and not everything needs to be explained.

I never try to explain my worlds to the reader. This makes it more mysterious and interesting.