14 Perfect Minutes: Breaking Down the Opening of 'Jaws'

From character introductions, to dialogue, to world-building, Steven Spielberg's third film is a master class in cinematic storytelling

Jaws (1975) is a master class in literally every aspect of filmmaking, but today I want to focus on its screenplay. In particular, how its opening pages set up its world and characters so well that fourteen minutes into the film you’ve already learned more about both — and the plot — than most films manage in an entire first act.

Because what shows up on screen is different than what’s on the page, I’m going to primarily discuss the screen experience, but, as I do so, I’ll also draw attention to how what I’m describing appears — or doesn’t appear — in the script. This will, I hope, help you to see how decisions during Jaws’ turbulent production and, later, in the editing room led to a more economical, effective story. What I just wrote should not be interpreted as criticism of Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb’s brilliant script. But in realizing it, exigent production realities and editing led to director Steven Spielberg making calls that streamlined certain details and made others land even more effectively.

Start to finish, this conversation is going to be about economic storytelling that makes audiences lean in while never resorting to lazy exposition.

EXT. BEACH

The film’s TEASER is iconic, of course. Two potential young lovers separate from a late-night/early-morning beach party to skinny dip together. The man, too drunk, struggles to disrobe on the beach. The woman dives in…and, moments later, is attacked by something that is only identified by John Williams’ now-iconic “duh-duh” “Jaws Theme”. The sequence lasts until about 05:03 into the film before the image of a blinking buoy in the night slowly dissolves to a virtually identical shot (sans buoy) — but it’s morning now, the sky blindingly bright.

The fact that five minutes have passed is important because I’m discussing the film’s first fourteen minutes here. That means everything else I’m going to get into happens in only nine minutes, even less time than I first suggested, given how much is narratively accomplished with them.

INT. BRODY HOUSE - BEDROOM - EARLY MORNING

(By the way, the sluglines I’m sharing here are lifted directly from the screenplay. You’ll find a link to it at the end of the article.)

Returning to my description of the shot of the ocean, blindingly bright — a shadowy figure rises into in the extreme foreground, peering out at the ocean that we’ll later learn scares him so much. In other words, his introducing is staring down his existential enemy — the thing he’ll have to overcome to ultimately triumph. This is a man vs. nature story.

As this happens, the radio issues a report about AMITY.

The location — the “world” — of our story has been established.

This, it should be noted, is different than the screenplay where other geographical details are mentioned instead. While what’s written is realistic, it confuses how the audience locates itself in the events they’re experiencing.

“How come the sun didn’t use to shine in here?” the shadowy figure asks. We still don’t see his face. Steven Spielberg is making us lean in, pay more attention.

His wife, ELLEN, lies in bed. We do see her face. She tells them the sun is so bright because they bought the house in the fall and it’s summer now.

Ah, they’re newcomers to Amity.

Her husband, whose name is BRODY, rises. We still can’t see his face, just hints of it. We’re leaning in hard now. Ellen asks him, “You see the kids?”

They have kids.

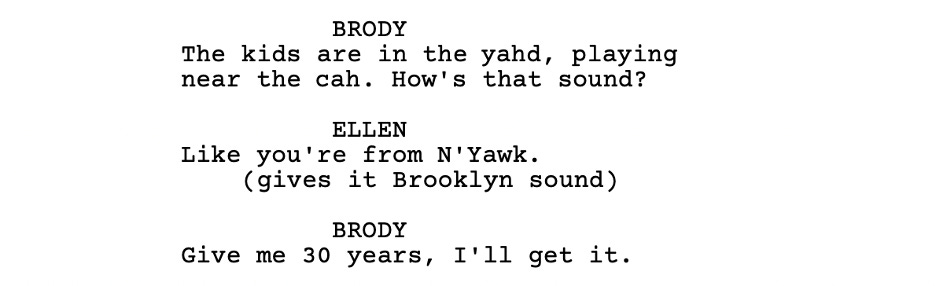

Brody looks out the window. “They must be in the backyard,” he says. But this isn’t some throwaway detail. It leads to a fun exchange between this loving couple that reveals even more about them.

Even if you miss the Boston accent Ellen slaps on the word “yard”, the intent is clear.

At this point, Brody finally turns to the camera, revealing his face. His next words answer the question about where they’re really from. Do you see what the script/film is doing? It’s making you, the audience, ask questions. Why is the sun so bright? What does Brody look like? Where are they from?

Got it, they’re from New York.

What’s more: They’ve moved to Amity for good.

You can interpret a lot from this. They newcomers, still settling in, still getting used to whatever “Amity” is after a huge life decision.

INT. BRODY KITCHEN - MORNING

Here, the phone rings. Brody answers it…except there’s nobody there. That’s because he picked up the wrong phone. He grabs the receiver off a second phone, beneath the other one.

See, another question for the audience to keep them engaged: why does this guy have two phones?

Consider how this plays out in the screenplay:

Spielberg’s staging of this is vastly superior because, again, you’re leaning in, you’re asking questions, you want to know more.

As for Brody’s dialogue, it’s vague and real. He’s responding to what someone else is telling him about events obviously related to our teaser…but why is anyone calling him about this? You’ll note, nobody has referred to him as a police officer of any kind yet.

An element of the screenplay that’s cut from the film is setting up Brody’s new glasses. Here:

These glasses were meant to be relevant to the finale of the film, when Brody, stripped of his glasses, is forced to take a critical shot at a pressurized air tank wedged in the titular Great White’s jaws. The film obviously works without it, so it was cut.

But it’s a lovely detail all the same.

This is followed, in the script, by Ellen kissing her husband as he leaves with a travel cup filled with coffee:

This isn’t what happens in the film, though. Spielberg moves this exchange outside the Brody household, to create a sense of movement to the act, where Brody climbs into a convertible SUV. It’s only here that Ellen calls him “Chief” for the first time.

“Listen, Chief, be careful,” she calls out. “In this town?” Brody replies. In other words:

Nothing dangerous ever happens here.

But it’s not just that. It’s subtle, but Brody’s ignorance of the double phone and the way Ellen calls him “chief” suggests something else:

This is Brody’s first job as the Chief of Police anywhere.

As he shuts the SUV’s door, we see AMITY POLICE DEPT. on it.

EXT. ISLAND HIGHWAY - MORNING

Brody drives past a sign that reads:

AMITY WELCOMES YOU

50TH ANNUAL REGATTA

In addition, the date July 4th is thrown out there.

Whether we realize it yet, the STAKES for Brody’s antagonists has been established. It will be explicitly stated within a few minutes.

EXT. AMITY BEACH - DAY

Brody questions the young man who failed to score with the young woman who was attacked in the teaser. This feels a bit extraneous at first, since it’s presenting information we more or less understand already, but two important things happen here you might miss on a casual viewing.

The first, the exchange establishes that the young man is a rich kid. Meaning, there’s a class component to Brody’s place on this island.

He is working class.

The second thing this scene establishes is the social hierarchy of the island and, again, Brody’s place in it. The young man might live off the island, but he was born on Amity. “Yeah, I’m an islander,” he says - establishing a special language appropriate to the setting. Then, he asks Brody, “You an islander?” Brody answers, “No, New York City.”

So, Brody will never truly belong on Amity Island - he is an outsider.

A moment later, only 08:40 into the film, the body of the young woman is discovered. We only catch a glimpse of her hand sticking out of a sand and mob of crabs.

INT. BRODY'S OFFICE - DAY

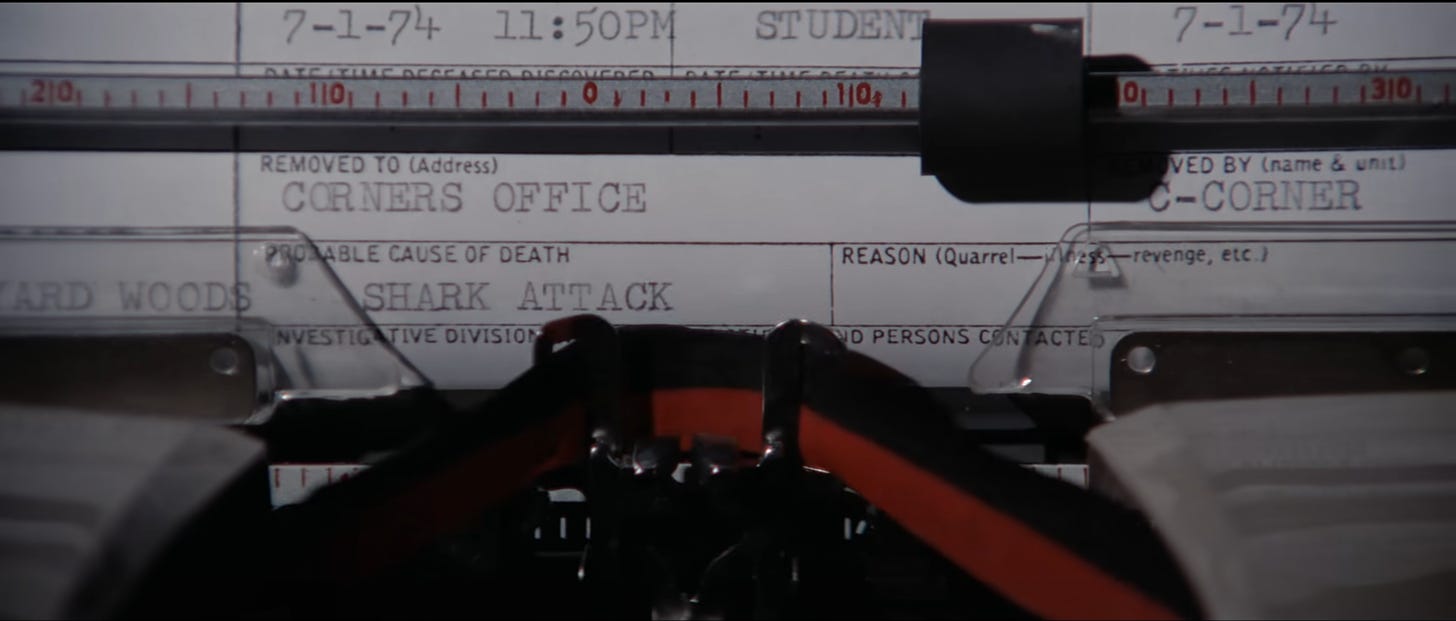

This is a frantic little scene that introduces Brody’s amusing secretary who doesn’t notice the horrible tension when she arrives for work. She can only prattle on about the minor issues Brody typically deals with like kids “karate-ing fences” as he fills out a form at his typewriter.

Brody’s job is a cakewalk compared to his life as a NYC cop.

The CORONER calls and tells Brody the answer to the question you might’ve had about why the police chief is typing right after discovering a dead body. In the space for Probable Cause of Death, Brody types what the film’s poster already told us:

Brody jumps up and asks his deputy, “Where do we keep the ‘beached closed’ signs?” He’s told, “We never had any.”

Brody now has a mission: close the beaches!

EXT. AMITY MAIN STREET - DAY

Brody hurries out of the police station to solve the problem created by the lack of appropriate signage in his department’s supply closet. In doing so, he gives Steven Spielberg the opportunity to visually establish the geography of this seemingly perfect small town. It couldn’t be more beautiful. There’s even a marching band rehearsing for a parade (how Norman Rockwell!) and birds singing loudly. Another sign reminds us that the July 4th celebration is almost upon us, to reinforce the antagonists’ stakes.

INT. HARDWARE STORE - DAY

Brody sweeps into the local hardware store to buy paintbrushes, boards, and other supplies to make signs. In the background, the store’s owner complains to a delivery guy about his order not being fully completed. He lacks the beach goods — like beach balls — to capitalize on the holiday. In case we’ve missed it:

The beach and, in particular, this holiday event drives the island’s entire economy.

EXT. AMITY MAIN STREET - DAY

Brody exits the hardware store as his deputy arrives to escalate the stakes with new information:

The Boy Scouts are in the bay testing for their mile badges.

Holy shit, kids are in danger! Brody speeds off to handle it, leaving the deputy to paint the signs. Meanwhile, THE MAYOR arrives and ask the deputy what all the hubbub is about.

“Listen, we had a shark attack,” the deputy says (I’ve trimmed a bit of dialogue here). “Fatal. I’ve got to batten down the beach!”

Note that Spielberg doesn’t show us the Mayor’s reaction to this. In depriving us of it, he creates yet another question for audiences to lean into: how does he react? Well, you’ll have to keep watching to find out.

EXT. FERRY LAUNCH - DAY

This location doesn’t appear at a ferry launch in the script. Brody just rocks up to the beach, to solve the problem, but Steven Spielberg, always keen to find movement on screen even when the camera isn’t moving, to create action or the implication of it, the sense of things happening, moves the scene to a ferry launch instead.

Brody boards a small car ferry and instructs the driver to take him out to the Boy Scouts. That’s when another car arrives, pulling right on to the ferry. Out climbs the Mayor, selectman/city paper editor MEADOWS (played by screenwriter Carl Gottlieb), the Coroner, and a couple others.

As the ferry heads toward the Boy Scouts, a visual ticking clock, the Mayor says he’s heard Brody is going to close the beaches “on [his] own authority.” Brody is confused. “Well, what other authority do I need?” he asks. It turns out quite a bit for something this significant.

“We’re really a little anxious that you’re rushing into something serious here,” the Mayor says. “It’s your first summer, you know.” Brody reacts by asking what he means by that and, while the Mayor is polite about it, it’s clearly a threat.

Ah-ha, the Mayor is our villain!

“I’m only trying to say that Amity is a summer town,” the Mayor says. “We need summer dollars.” If people can’t swim here, they’ll go to other beaches, he warns.

The economy is all that matters to the Mayor.

Implicit in this concern is maintaining his position of power in the community. He is an agent of commerce, of capitalism, of dollars over human lives.

Brody expresses his concern about prioritizing summer income over the threat of a shark, only to be dismissed by Meadows. “We never had that kind of trouble in these waters.”

It’s at this point that we, the audience, realize the car ferry isn’t approaching the Boy Scouts as we thought. It’s pulled a U-turn, and is already heading back to the launch ramp. In other words, Brody has already lost, even if he doesn’t realize it yet.

The Coroner goes on to suggest that the young woman’s death wasn’t actually a shark attack, as he first said. It was a “propellor accident.” When he’s challenged for changing his story from what he told Brody on the phone, he says, “I was wrong.”

While Brody accepts that the Coroner has reconsidered his professional opinion solely on the basis of evidence, we in the audience know better:

Money will change the interpretation of reality regardless of the risk to this community.

“It’s all psychological,” the Mayor warns Brody. “You yell ‘barracuda’, everyone says, ‘What, huh?’ You yell shark, we’ve got a panic on our hands on the Fourth of July.”

This is what Brody is up against - the island’s elite. It’s working-class cop versus the upper class. And people will die because Brody accepts his place in the island’s social hierarchy.

The Mayor tells the ferry driver, “Okay, you can take us back now.” Scene over.

The car ferry scene concludes at 13:40 into Jaws having established in a brisk, but naturalistic way everything we need to know about this world and the characters in it to understand the rest of the film. In many ways, a three-act play has actually transpired to accomplish this, too.

Act 1: The Teaser with an Incident Incident (dead body)

Act 2: Establishing our characters, establishing our conflict, and setting our hero on a mission to save the Boy Scouts.

Act 3: Our hero is defeated by the forces of commerce. Remember, stories don’t have to have happy endings.

After this mini-play, the story almost resets in a new direction when a young boy is attacked by the shark, dying in a bright geyser of bloody ocean water. This death implicates Brody, because he could’ve prevented it. One reading of it might be as the film’s INCITING INCIDENT, setting the film’s real action in motion. But I think that’s a mistake. I would call Brody’s defeat on the ferry the film’s Inciting Incident. Remove it, and there is no film. The boy lives, the great white is hunted down, and this particular Fourth of July just becomes an unfortunate memory for Amity rather than a blood bath.

Now, go look at your latest draft. Look at those first ten to fifteen pages through the lens of this article and Jaws. What are you doing to get readers to “lean in”? What should you have cut out because, while great ideas, they proved unnecessary (like Brody’s glasses)? What dialogue is there to get right to the point as laid out in your outline rather than naturalistically expressing the same thing in a far more interesting, character-driven way? What thematic work is underpinning (almost) every scene?

Basically, what would Steven Spielberg do?

I know, I know, it’s not that easy. But that doesn’t mean you can’t at least try to apply the principles you’ve found here to your own work.

You can read the screenplay for Jaws here.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

You have made me want to rewatch the film and reread the book now. I love Peter Benchley's writing and remember reading both Jaws and The Deep and being immersed. Great, read this.

Did you notice the (literal) typos in that form that Brody is typing? In both places he types “CORNER” instead of Coroner. I wonder if this was intentional, and if so why. Seems a strange, small detail. I can almost hear it said with a NY accent and a Boston accent. Unlikely to have been just a mistake, I reckon. What do you think?