What's In the F@cking Box?! (Or: What Quantum Mechanics and Art Have in Common)

It's impossible to pretend away the fact that what we create changes once it interacts with the rest of the world...but what if we embrace that?

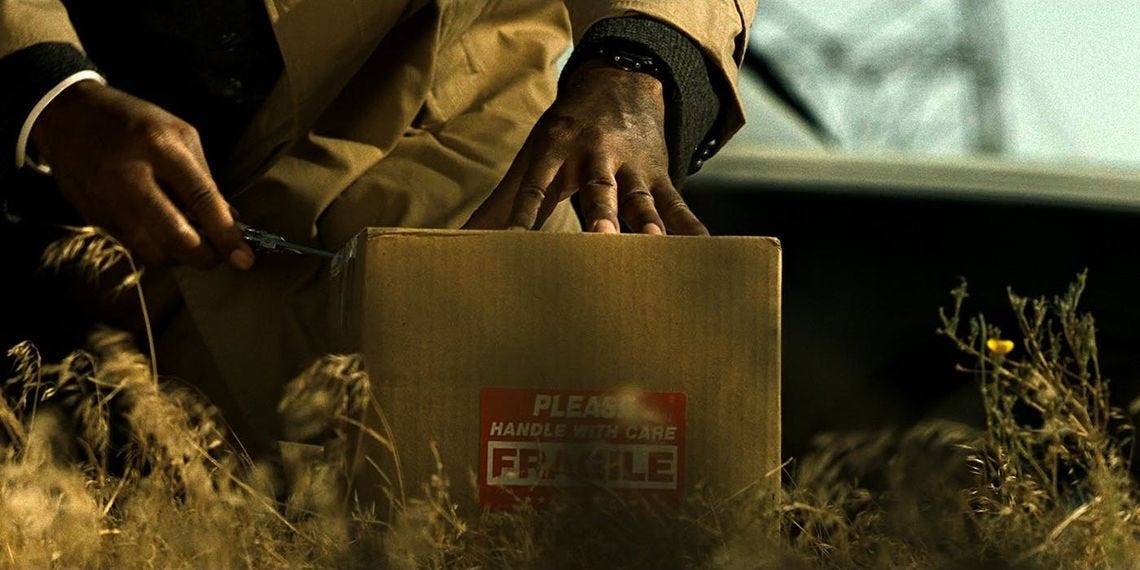

Brad Pitt is standing in the desert outside Los Angeles, shouting at Morgan Freeman to tell him what’s in a box that’s just been delivered to them by a FedEx guy who deserved but didn’t get a big tip for driving all the way out here to the middle of nowhere. Pitt’s character, a cop, suspects the answer is the decapitated head of his wife, but he needs to know for sure because, come on, who wouldn’t want to know if his wife’s decapitated head is or isn’t in a box? It’s one of the most horrifying moments I’ve ever seen on a movie screen.

“What’s in the box?” he cries out, his face twisting with anguish. “What’s in the fucking box?”

Everything you’re about to read won’t make any sense…until it does. And when it does, you might just find yourself embracing the unknown in your storytelling.

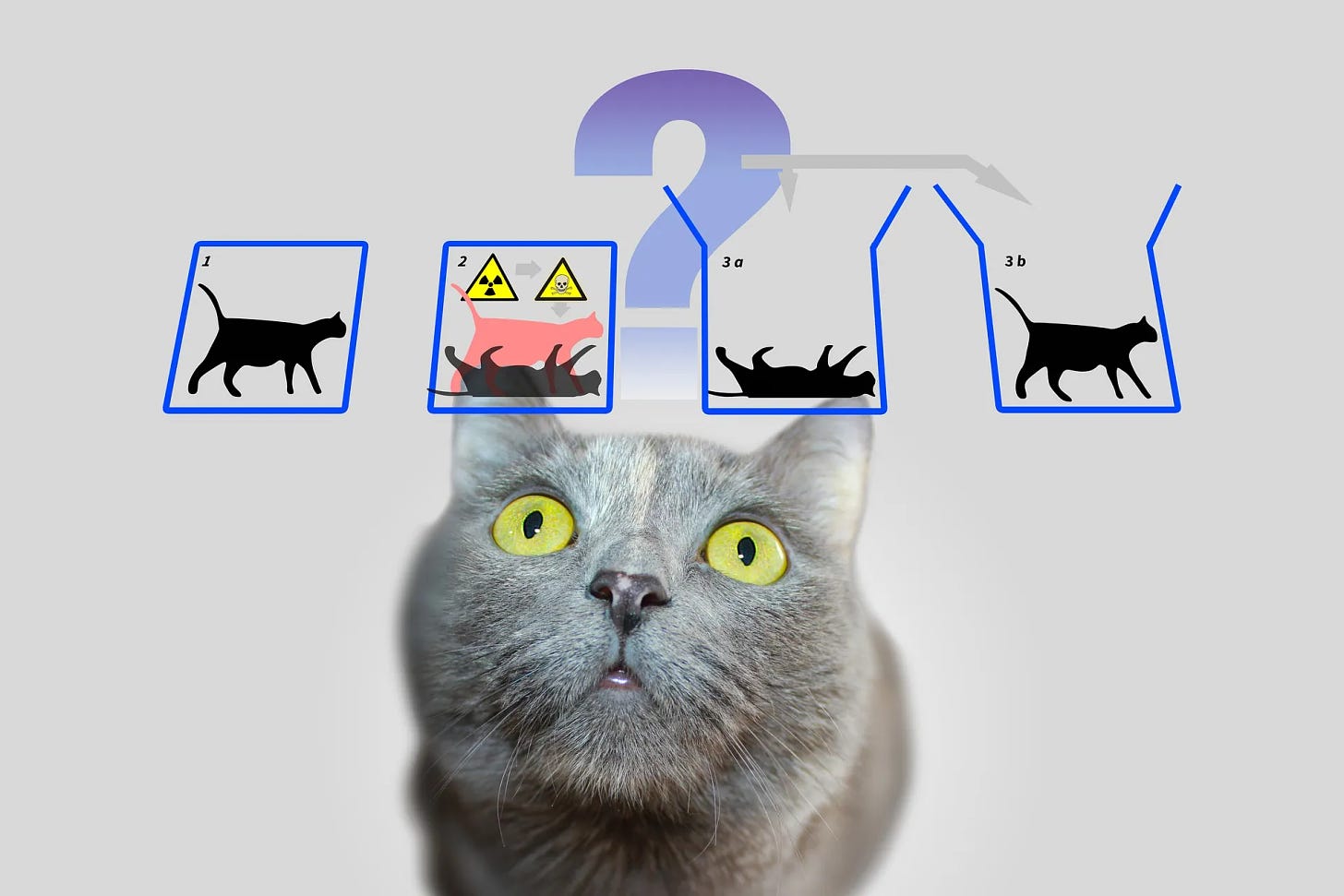

Do you know the thought experiment called “Schrödinger’s cat”? I learned it in grade school, which in hindsight seems a bit mad, trying to teach such young children about quantum physics. But that’s what the experiment is, an attempt to illustrate the paradox that is known as quantum superposition.

If you don’t know, quantum superposition is the idea that a quantum particle can exist in mutually exclusive conditions at once that, until observed, won’t settle on being one thing or the other. For example, a photon can be polarized so that the electric field inside it wriggles vertically, horizontally, or even both ways – all at the exact same time. It’s essentially a photon with multiple personality disorder.

According to the Copenhagen interpretation, a quantum system remains in such superposition until it interacts with or is measured — until it is observed — by the external world in some way. When this happens, the superposition decides on one of its many possible states.

In Edwin Schrödinger’s thought experiment, there is a cat in a sealed box with a flask of poison, a radioactive source, and an internal monitor. If the monitor detects radioactivity, the flask releases the poison and the cat dies. But you would never know which state the cat is actually in because the monitor doesn’t alert you either way. In other words, it is simultaneously alive and dead because it cannot be either until you, a human observer, open the box and look inside to find out.

It might even be said you decided the cat’s fate.

Quantum superposition is a subject I’ve long been fascinated by, almost as much as I am the nature of our reality, which I explore in my debut novel Psalms for the End of the World. I find it fascinating that so much of quantum mechanics can be explained by imaging our universe as part of a digital conversation. Here’s a passage found late in the book:

“Let me ask you this,” Jharna said. “Your kids, do they play video games?”

“The youngest one,” Mimori said.

“What’s her favorite game?”

“It’s one of those first-person shooter games,” Mimori said, unconsciously shuddering at the thought. “I hate it. Super Zombie Killer Force, I think it’s called.”

“My son loves that game,” Jharna said. “It’s VR, so it requires a lot of computing power given how large its environment is. I presume you’ve tried playing it with her?” Mimori nodded. “There’s a building in it outside Atlanta somewhere. Abandoned, broken windows, but you can’t see inside. You don’t know what’s in it, but you think you should find out because you’re running low on bullets and zombies want to eat your delicious brains. What do you do?”

“Go inside.”

“Of course you do. But ask yourself: was the building interior already loaded as soon as you powered the game up, or was it waiting in deep storage, along with all the possibilities that might exist within, for you to open the door before it loaded? In the first case, that’s a lot of computing power. If every building, if every location in the game is fully loaded all the time, the game would crash. In the second case, only the world immediately around you taps all that computing power and, as a result, you get a more convincing first-person experience.”

“So, the inside of the building doesn’t exist until I step through the door. You’re talking about Schrödinger’s cat again.”

“I’m talking about the human element, which is excluded from all quantum theory. Human consciousness, more specifically. Human beings give shape to reality in a computer simulation, explaining the measurement problem. Quantum physics is too absurd, too unexplainable by any model we’ve come up with, because every time we take a peek at something in the quantum realm, we change it. There are no zombies on the other side of the door until you walk through the door, Mimori. The goddamn cat doesn’t even exist until you open the goddamn box.”

Jodie Foster is discussing the writing process on the podcast The Screenwriting Life not so long ago. She observes how lonely it is compared to her own experience of the creative process as a director and actor, which comes much later. A screenplay in production, she suggests, reacts like photographic paper when it’s exposed to oxygen.

“Stuff happens,” she says, “because some person that you're working with asked you a question or the [actor] that you're working with isn't good at [something], or can't bring this one part of the character because it doesn't feel true to them. Or they had some idea about a funny hat they were going to wear - and suddenly everything has to change because [the screenplay] came into contact with other human beings. And of course, as a director, this happens 140,000 times a day because other factors — whether it's the weather, whether it's the schedule — all of it impacts on some idea you had all by yourself.”

I’m chatting with multi-Eisner-winning comic book writer Matt Fraction for one of 5AM StoryTalk’s artist-on-artist conversations. He’s discussing Plot Style, in which a comic artist works from a writer’s story synopsis/plot rather than a full script. The artist then illustrates the book, creating page-by-page plot details of their own, at which point the work is returned to the original writer for the insertion of dialogue.

Fraction tells me that back in 2009, fellow writer Brian Michael Bendis argued “Plot Style wasn’t really writing, that it was lazy and non-committal.” As for Fraction, he found the idea of it unsettling. “It made my stomach hurt a little. It felt like I’d be taking my hand off the wheel of the car or something. It was intimidating in the utmost. So, I decided that, well, fuck it, I at least had to try.”

The result?

“It kicks ass. I find it 100% more collaborative, more surprising, and the results more visually powerful. Less taking my hand off the wheel, it’s more like taking a trust fall. It feels more like improv or something – yes and-ing back and forth until the printer comes to take the book away.”

Fraction continues: “The practical reality is, I think – I know – it made me a better, more open, collaborator. I love being surprised by a thing that used to be mine, but now is ours. I love when the thing becomes more than the sum of its parts.”

My editor at Headline Books and I are having a Zoom a few months after he bought Psalms for the End of the World. Toby Jones — the editor in question — wants me to know how much he adores the structure I used to tell Psalms given how it helps ease the reader through an otherwise narratively complicated book.

There are three “books” within the novel, which is what he was referring to; or, a “three-disc concept album” as I prefer.

The thing is, this wasn’t the novel’s original form.

The manuscript I submitted to agents was roundly rejected by all except one because, I now believe, it lacked such structure “to help ease the reader through an otherwise narratively complicated book.” That came later, after I had signed with the one agent interested in my work (who, thankfully, I also found brilliant).

This new book agent, an exceedingly lovely man named Jon Wood (RCW Literary Agency), had a question he wanted me to consider: is there any way to make the book easier to read while not losing anything that we both agreed was special about it?

I bristled when he asked this, worried he wanted me to dumb the novel down in some way. I was accustomed to this note from Hollywood producers regarding my screenwriting. But he was insistent that was not the case here. I wasn’t to change anything about the actual story, but…well…could I just think on it? Consider it a challenge.

Now, I wasn’t necessarily surprised by this note. Once Psalms left my hard drive and entered the real world, where others could react to it, interact with it, and tell me what they loved or even hated about it, it was inevitable it was going to change in some way. I could either resist or trust myself to help the novel settle on its true form.

I returned a couple of weeks later with a solution. I had reformatted the non-linear chapters along three themes of spiritual awakening: Liberation, Suffering, and Rebirth. This is the structure I’ve already described - three books, or a three-disc concept album.

My book agent responded a few days later. I had done it. Within a couple of weeks, he began submitting Psalms for the End of the World to publishers.

Today, I believe Psalms was always supposed to exist in this form, the one that manifested when my agent “measured it”. If you ask me what it’s about, I still typically demur, pretending it’s too big of a book to describe. But really, I prefer it to define itself based on the life experiences of each reader. It’s not much more than a pile of paper and ink without that interaction to provide it with unexpected, wholly subjective dimensions.

Jodie Foster suggests writer-directors have the most trouble accepting how their screenplays react to the realities of production:

“They come up with something in their hotel room, and they think it's perfect and it's just amazing, and they live with it for months and months at a time,” she says. “And then they come onto a movie set and they are unwilling to understand that the whole beauty of it is that it's all going to change the second that it comes into interaction with other people.”

Kevin Spacey’s serial killer character is taunting Brad Pitt because he wants Pitt to kill him. It’s the fulfillment of his sick plot, which revolves around the Seven Deadly Sins. Pitt must answer his alleged envy with wrath for him to be victorious.

“What’s in the box?”

Morgan Freeman, Pitt’s partner, is in a bind. He knows what’s in the box, but he’s looking at a second box of his own, this one metaphorical, in the form of Pitt’s character. In this moment, Pitt simultaneously exists as both a good detective and as a vengeful murderer with no future. He’s both alive and dead, in a manner. If Freeman tells him the truth, Pitt will have to decide which he is.

Freeman looks at his partner, unable to hide what’s written all over his face. He reasons and he pleads. And Pitt reacts, becoming wrath.

The story of your art doesn’t actually end when you type THE END at the into your novel or screenplay, or paint your name along the bottom of a canvas, or finish working the kinks out of the next song you intend to record. It’s just the beginning of a larger mystery as confusing and demanding of patience and consideration as quantum physics. It can surprise, it can terrify, it can illuminate. Just don’t be scared of it happening, because it will whether you like it or not. Sooner or later, it’s time to find out what’s in the box.

My debut novel Psalms for the End of the World is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Fantastic post. Love your insight on the struggle between being a creator and being a collaborator and how the story always finishes in the mind of the audience. It reminded me of another another piece I read (I think on substack) about "serialized" novels written by Dickens (and others) who had their stories constantly tested in the market place by real world readers and how those stories were shaped week to week/month to month...compared to the Hemingways who agonized in the dark over single pages...

Fantastic