Q&A: Filmmaker Scott Frank Doesn't Know What Happens Next

The creator of 'Godless', ‘The Queen’s Gambit’, and 'Monsieur Spade' reflects on time, finding his own voice nearly 30 years after first finding success, and the virtue of making it up as you go along

Let’s start with the story about how I met filmmaker Scott Frank seventeen years ago. He doesn’t remember this story, but I do.

I began my career in Hollywood as an arts journalist, primarily interviewing musicians and filmmakers of all stripes. Somewhere along the way, I realized I had the chance to sit down with Scott, who had written Out of Sight (1998). I don’t want to shortchange his other work before this now-iconic crime film; Dead Again (1991), Little Man Tate (1991), and Get Shorty (1994) are all wonderful - Get Shorty, in particular. But Out of Sight? Jesus, you have to understand what a formative film in my life it was; partly because it recognized Detroit, where I grew up, as an interesting, even beautiful place that deserved to be on the big screen, but also because of how Scott’s script wove a time-jumping mystery that made Pulp Fiction’s non-linear narrative seem simplistic by comparison. Out of Sight was a kind of gateway drug to a new way of telling stories for me. My debut novel Psalms for the End of the World, which disregards linear narrative to an even greater degree, would probably never have happened without this film. Hell, a lot of my work wouldn’t exist, at least not in any way I currently recognize, without Scott’s work on it.

Long story short: I needed to talk to this guy back in 2007. Scott’s newest film, The Lookout – his directorial debut – was about to hit screens, so I convinced an editor I knew that it was worth paying me to cover. I parked six blocks away from the Beverly Hills Four Seasons to avoid paying for the valet (money was tight back then), gorged myself on the press day’s free buffet (money was tight back then), and waited patiently for my turn (working on another article due later that day because did I mention money was tight back then?). Finally, the publicist told me I could head in. Holy shit, I was going to interview Scott Frank!

I sat down beside him on a couch and asked my first question. I don’t remember what it was, but I know I didn’t ask fluffy questions even back then. By the time I started to ask my second question, maybe three minutes into the conversation – four minutes max – Scott interrupted me mid-sentence and asked, “You’re a screenwriter, aren’t you?”

He had recognized right away I was much more interested in story and craft than talking about the stars of his film or getting him to slip me something juicy about his next project I could turn into clickbait. When I answered yes – still a weird thing for me to claim as I wasn’t yet a professional — he told me, "Ask me what you need to ask as quickly as you can. Let's get this over with, and get to the stuff you really want to talk about."

Five minutes later, not even ten minutes into my 30-minute 1:1, I was done with my Lookout interview and Scott had given me efficient answers to what I was after for my article. He then spent the next thirty minutes, exceeding my allotted time limit with him, discussing writing in whatever direction I wanted to take the conversation. This was not a great time in my life, I should point out. I’d been in L.A. for almost two years and I’d failed to make any real inroads in “the business”. I felt like a nobody. But for a brief moment, when I was still dreaming of success in Hollywood, struggling and despairing, Scott behaved like a saint and I will never forget that.

All these years later, I’m now a produced screenwriter with more than a decade-and-a-half of experience behind me. You’d think that would’ve prepared me for my first chat with him in almost as long, but I was still nervous as all hell when I hit connect on the Zoom invite. You don’t get to talk to one of your idols every day. I doubt I was any less nervous than I was when I first sat down with him at the Four Seasons to talk about his first foray into directing.

But once again, Scott was just…well, he’s the man.

What you’re about to read is a conversation that shifts in many different directions, at times craft-centric, at times philosophical, at times affirming (which will make sense later, I hope). What I will say is that I didn’t come into it with a specific agenda beyond wanting to talk about the role and fluidity of time in Scott’s films and TV series. From Dead Again to Out of Sight, from Logan to “The Queen’s Gambit”, time – and memory – are major themes in his work. Because I wanted to just sit back and enjoy myself, come what may, there is an extremely casual flow to what we get into here. I think what I’d like you to pay special attention to, though, is Scott’s reflections on the breadth of his career, how he got here, and the lessons he didn’t learn until he was already a veteran scribe.

COLE HADDON: When we started emailing about having this chat, I shared the story about our first meeting and what your generosity meant to me, as an aspiring screenwriter, at that time in my life. I wanted to start by asking you, who’s the first screenwriting hero – or whatever you want to call them – who took the time to recognize you?

SCOTT FRANK: Well, the first one was my hero – Bill Goldman. I started working in ’84, and I met him in ’90. So, I'd been working for a while when we met, and he just changed every aspect of my life. He’s even the reason I live in New York City today. He was an incredible, incredible mentor.

CH: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Marathon Man, The Princess Bride — I mean, they don’t come any better than him. How did you two cross paths?

SF: It was for a shitty movie that we were working on for Castle Rock called Malice. But he was absolutely amazing, and became a big part of my life from that point until his death. Reading Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid when I was a kid really affected me. I thought, “Oh, that's cool. ‘Butch delivers the most aesthetically exquisite kick in the balls in the history of modern American cinema.’” That's in the script. “Fuck, I'm going to write one of those.” I was eleven.

CH: [Laughs] Yeah, Goldman’s script is truly remarkable. I learned so much about writing for film from it.

SF: The person who changed my life about writing though was Lindsay Doran. She was a studio executive and then a producer, and she – for all intents and purposes – taught me how to write movies. I thought I knew after I'd written Little Man Tate. No, she really taught me how to write, how to write movies.

CH: Can you explain that? In your mind, what did you get wrong before you met her?

SF: I was going too fast. I wasn't stopping and thinking. I didn't recognize that with such little real estate, every bit of it was precious, and so you want to make everything count every little moment. It shouldn't be vague. There should be a specificity to everything you put in the script. It's not just an elevator operator or a shopping clerk or something – there's always room for an attitude, or a character, or a quirk, or something.

CH: Color.

SF: Yeah, she really taught me that. But the biggest thing she taught me was how to solve problems, how to look critically at them – not in terms of the rules of writing, but in terms of just thinking about poetry, or other examples of how they did things, and other stories, and looking at it that way. And there is no right way or wrong. There's just the way that feels right.

And then Steven Soderbergh became not so much a mentor. He is in a way, but more just an incredibly honest, tough friend. That sort of was the next thing I really needed. And he delivered that at exactly the right point.

CH: Soderbergh is a good place to transition to a subject I’m keen to discuss with you. Time is often non-linear, or say flexible, in your work. Memory and fate, past and sometimes the future, all seem to regularly intersect with the present. Myself, I used to think of time as a narrative device, which is how I’d describe its use in, say, Out of Sight – which Soderbergh directed. But as I’ve grown older, as the years have accumulated, it’s taken on a very different meaning for me. It feels more fluid now, closer to how you employ it in “The Queen’s Gambit” — which, for readers, I’ll point out you created and wrote and directed in its entirety. Tell me, what does time mean to you as a person and storyteller? And has your relationship with it similarly changed over the years?

SF: I mean, at this age, time is all I think about. It's all I think about is the fact that there isn't a lot of it left.

CH: [Laughs] Fair. What about when you were younger?

SF: It was constantly on my mind when I was younger, too. We all feared death, but acted like we were going to live forever. That was my sense of time.

CH: What about as a storyteller?

SF: For me, time in storytelling is a storytelling device. It's a way to fold the structure in so that you can look at things in a different way. Sometimes, it's better to just play it straight and sometimes it's really interesting to double back. And sometimes doubling back is a crutch, there's another way to do it. Sometimes it's a great rhythmic thing. It can break things up to go backward and go forward. It can be very novelistic if you do it right, but people can tune out and not be with you if you do it wrong. How many times do you bump when they cut to a flashback? “I'm so not interested in this, I don't need to know why he became a cop.” So, there's a lot of that stuff to consider. But for me, the structure is a thing that you can fold and rearrange and use to have things happen. And as you unfold it, the unfolding of it becomes the story. And so, time is a function and structure is a function of time – or vice versa, I guess.

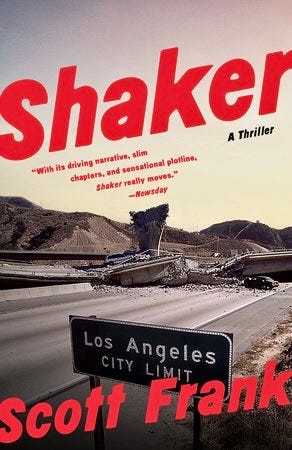

CH: Change, you might also say, is a function of time. A few years ago, after many years as a professional screenwriter, I started writing a novel. It was a terrifying prospect because I hadn’t written prose in more than a decade, and I worried screenwriting and everything that came with it had polluted my voice during the intervening years. I had surrendered something of myself to the craft, to the collaboration, and I felt I had to recover it in Word instead of Final Draft. The freedom I experienced both changed how I wrote going forward and made me look back with mixed feelings about the scripts that preceded it. Can you talk to me about Shaker, your own debut novel? About what you felt just before you started writing it. About the thrill of turning out those first chapters. And about how the book changed you, your creative life, and your screenwriting – good and bad?

SF: Excellent question. I wish I could just write books and still have the fancy life that I have. I really, really wish that more than six people read Shaker; and I'm writing a sequel to it now that no one will read. But I don't care because the answer to your question is, it was liberating because I didn’t know what I was doing. I would come in the morning and just as a kind of warm-up. I would work on the book. I just said, “I'm just going to write and I'm going to have fun with it, and I'll apply a more practiced eye later. I'm going just going to fail through this.”

Listen, no one is going to study my prose in Iowa or Irvine or anywhere. But I felt like, for me, I could tell everything I wanted to tell in the story. And it's why I'm so frustrated with the format with screenplays because it's such a limited, rigorous format, and there's only so much real estate, and you only get sight and sound and that's it. And so, it's really a challenge, and that's why you're using transitions or time or things you're using, every tool you can use to help you augment the fact that you only have sight and sound for 120 minutes or whatever.

CH: Do you think the process of writing Shaker changed you at all as a writer?

SF: It loosened me up because I was able to trust myself. It opened up something. Whereas with screenwriting, I felt like I had hit the hard pan and the reason I directed The Lookout was because I was bored. I felt like I'd sort of done a lot as a screenwriter and I wasn't interested creatively anymore. I just wasn’t. It wasn't that it's difficult. Writing is the hardest part of filmmaking – hands down – the most difficult part to get right. And most movies you don't like, it ain't because of the direction or the acting. Ninety percent of the time it's because the script didn't quite get there – and 90% of my scripts don't quite get there. Whereas, with writing a novel, it was different. It felt like I could spin a yarn, but in a different way, where anything was possible and there was no pressure in the way I feel pressure as a screenwriter.

CH: Was fear part of the enjoyment? You mentioned not knowing what you were doing. I imagine the challenge you face as a screenwriter isn’t as daunting when you've reached a certain level of experience.

SF: Well, every story is a challenge, I would argue. But fear is always a factor, and I always talk about that. But with the book, it was faith. I said, “I'm going to just have faith that it's going to get done, I'm just going to stay with it and see what happens and not give up. And I may go off the rails here or I may go off the rails there, but I have an editor and so we'll see what happens.” Also, because I had such good mentors – excellent, excellent mentors – I had a lot of voices in my head at the time. I wanted to just set them aside for a minute and do my own thing, answer to myself, just hear my own voice. I felt like a new medium was the way to do that. I don't know that that was so intentional, but that definitely became a part of the experience, something that I learned in the experience. It was a great way to build that sort of confidence in my own voice.

CH: Did it force you to reflect on your previous screenwriting? Maybe change how you were working as a screenwriter going forward?