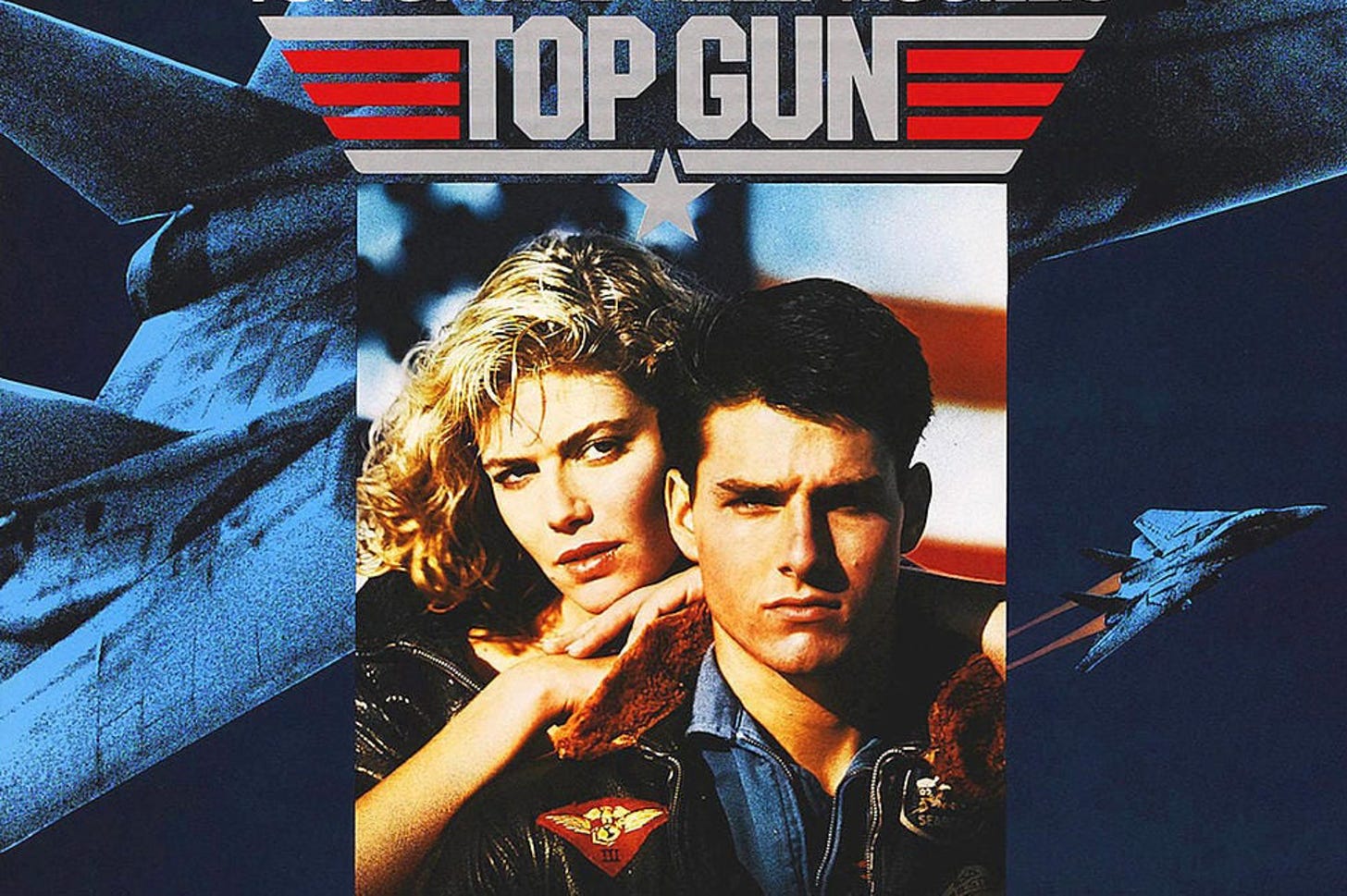

What if Maverick Is 'Top Gun's' Real Villain?

For all of the film's machismo, director Tony Scott's classic is actually a deconstruction of toxic masculinity

Last year, I shared an essay that breaks down why Top Gun: Maverick (2022) is a Master Class for storytellers in how to introduce your protagonist to audiences - which you can read here. Now, I want to share some thoughts on the misunderstood themes at the heart of the original Top Gun (1986).

For starters, Top Gun’s script — from Jim Cash and Jack Epps, Jr. — is tight and close to perfectly constructed from a contemporary cinema perspective. For another, it’s beautifully shot and edited. And another, it’s a hell of a thrill ride. But I think what makes the film truly great is something rarely discussed.

Some context first. For most of my time working in film and television, I’ve heard people in Hollywood refer to Top Gun as a “hyper-masculine film” or similar. Fun, sure, but definitely a great example of bro’d-up toxic masculinity from director Tony Scott.

But here’s the thing…it’s not.

Ironically, it’s a vociferous deconstruction of the very hyper-masculine culture people sometimes mistake it for. Consider Tom Cruise’s hotshot pilot Maverick - who is not Top Gun’s hero when we meet him. He might be our protagonist, but he’s very much a villain from the POV of his peers.

Maverick is a tragic villain in this case, sure — sad backstory and all (dead dads have always helped us forgive a lot in our male characters) — but the reason he’s so unpopular is that he’s a threat to the good guys in the story.

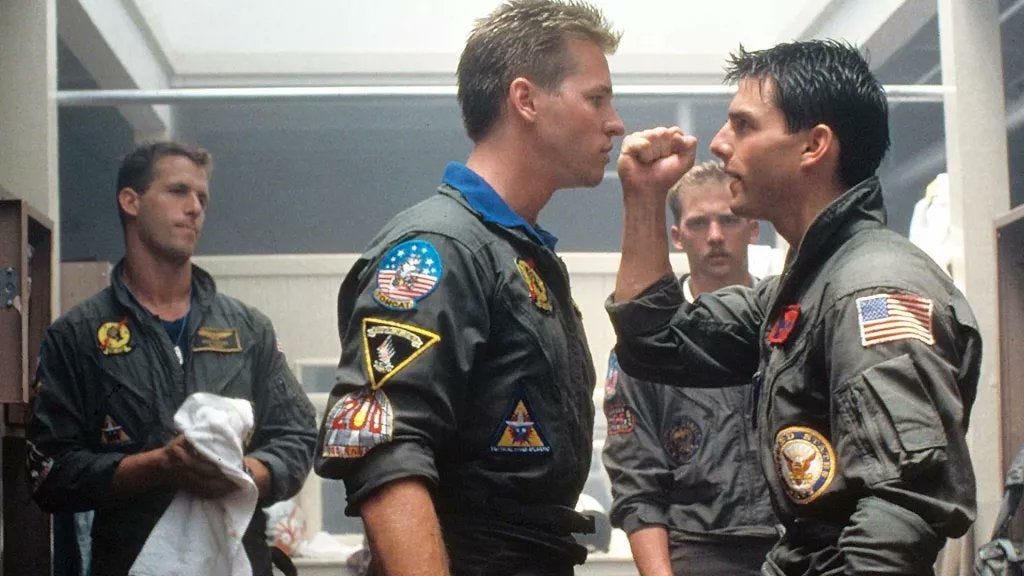

The other pilots, led by Val Kilmer’s Iceman, are afraid of him.

He’ll get them killed.

They keep him at arm’s length, never embracing or trusting him, because he believes he can go it alone, the rules somehow don’t apply to him, that his exceptionalism will also excuse him.

Maverick’s arc — which hits its low point when Goose (Anthony Edwards) is killed during a training exercise that may or may not have been Maverick’s fault— is to redeem himself. The bad guy must become the good guy if he is to become a true hero for the ages. And he is supported in this journey by a legion of men who only want to see him succeed, from Iceman to his mentor Viper (Tom Skerritt).

As for the toxic masculinity the film deconstructs, consider that for all the bravado the pilots seem to radiate, they spend almost no time on screen actually competing with each other despite the (fictional) “Top Gun” competition at the center of the film.

These pilots also waste only a couple of comments on anything that one could call “locker room talk” or even more broadly offensive. Locker rooms in Top Gun are instead used to offer emotional support and confront recklessness that endangers the group.

Many also toss around the term homoerotic to describe Top Gun, inevitably citing its infamous volleyball scene. Narratives about the military have historically hummed with such so-called homoeroticism, given the intimate relationships men develop with each other in war.

But is this homoeroticism or actually men, straight and queer, developing deep, meaningful relationships with each other that we, as a wider culture, cannot accept as emotionally healthy and free of the very toxic masculinity we spend so much time denouncing today?

In the case of Top Gun, while it certainly feels homoerotic — as much because of the content as how we’ve been engineered to perceive male intimacy, as I just described — I think that “homoeroticism” is instead the result of director Scott shooting a film for the female gaze rather than a typically male one. Rewatch those locker room scenes. Rewatch the volleyball scenes. And ask yourself if these half-naked, ripped men glistening like Greek gods are there for the entertainment of the straight men in the audience…or women (and gay men and anyone else who gets off on it)?

Of course, attraction and eroticism confuse gender lines, including for straight people. This analysis is not meant to dismiss the complexities of sexual orientation and how anyone enjoys other human beings.

Top Gun isn’t a “movie for macho men”, is my point.

Instead, Top Gun is a film made to confront toxic masculinity, which both men and women have reacted to over the decades. It’s also meant to provide a lot of eye candy, which both men and women have enjoyed. Unfortunately, I think the sugar has too often distracted from the substance.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

I love this reading of the film. I’ve watched it many times, but not for a few years. I’m keen to go back for another look.

But is this homoeroticism or actually men, straight and queer, developing deep, meaningful relationships with each other that we, as a wider culture, cannot accept as emotionally healthy and free of the very toxic masculinity we spend so much time denouncing today?

Thank you. Tangential but the "hahaha they're gay" shitty takes about Frodo and Sam in LOTR it drove me up the wall