Luke Skywalker Isn't the Hero You Want Him to Be

George Lucas might've given him a 'hero's journey' to follow, but that doesn't necessarily mean the character is on a quest to become one

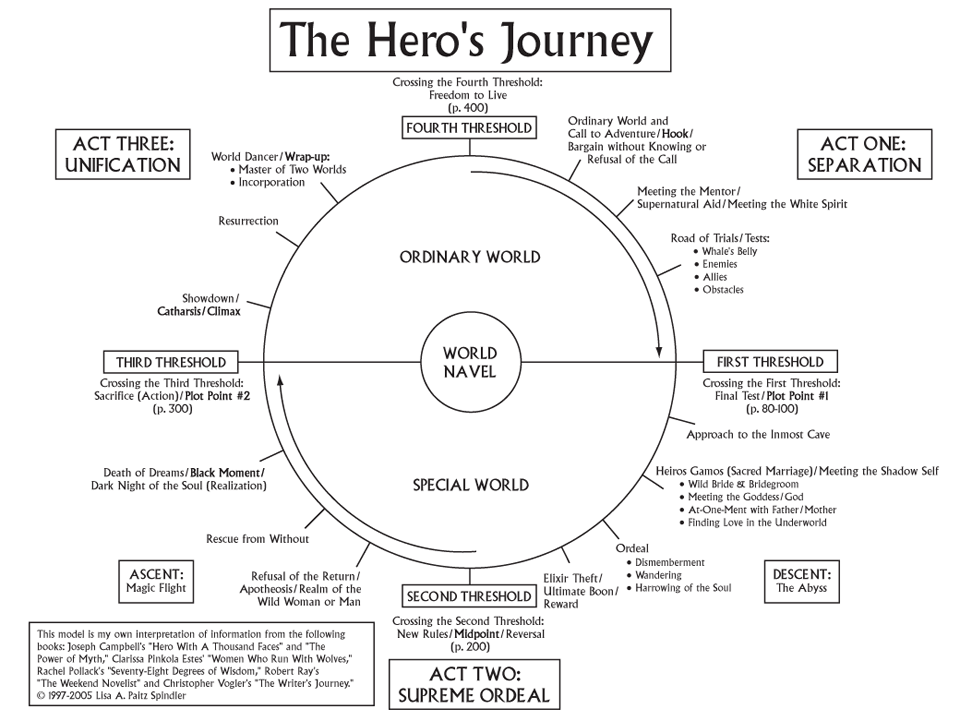

If you’re a serious STAR WARS fan, you almost certainly know the Original Trilogy was constructed around Joseph Campbell’s theory of the monomyth, or, as it’s more commonly known, the “hero’s journey”. In his book, THE HERO WITH A THOUSAND FACES (1949), Campbell proposed a common template of stories — what you might call a repeating pattern of myths across cultures — that involve a hero who goes on an adventure, is victorious in a decisive crisis, and returns home somehow changed or transformed by secret knowledge. He even broke the template down (which you’ll find below). Not even three decades later, George Lucas then slavishly followed this template when telling Luke Skywalker’s story in A NEW HOPE and then, again, when expanding that story across three films to tell an even more epic version of his young protagonist’s transformation.

The problem is, Luke doesn’t fit very neatly into Campbell’s template despite how we’ve all become accustomed to saying he does. This is mostly because Luke lacks any serious emotional motivation for most of the series, a stark contrast to, say, the Greco-Roman myths that Campbell obsessed over. Odysseus had to get home and take back his kingdom, for example. Hercules needed to atone for murdering his wife and kiddos, as another. Jason has to quest with the Argonauts after the Golden Fleece as a means to reclaim his father’s throne.

But what similarly drives Luke?

“Become a Jedi like his father before him” just doesn’t cut it. One of the reasons this narrative pickle exists is that Luke Skywalker lacks any kind of discernible moral core, outside of one personal rule, to compel him in any direction. He has no stated mission that matters both to him and to the galaxy. Instead, he has a mythical mission — which is to adhere to Campbell’s template of the hero’s journey — that he spends most of the trilogy trying to avoid.

Consider the following:

On one hand, we know Luke’s journey is a hero’s journey because it hits every one of those mythological beats we understand deep in our race DNA at this point. In fact, he does what Campbell tells us “heroes” do — and what pop culture in general tells us heroes should do — and he performs those responsibilities with gusto. Except he does all this without discernible reason or, if you dig really deep into what’s going on, most typically for the wrong reasons from a narrative POV.

On the other hand, Luke begins as an ignorant, immature and impetuous, emotionally erratic man-child prone to overblown attachments to relative strangers. More problematic, he demonstrates increasingly selfish and self-destructive behavior over time and always prioritizes his perceived inner circle and family over the greater good of the galaxy.

Another way to put this is: Luke’s real journey isn’t to become a hero according to Campbell’s definition of one…but to grow up.

When we begin to consider this “coming-of-age story” as not just a minor aspect of STAR WARS: THE ORIGINAL TRILOGY, but the only one that truly matters, the films becomes far more emotionally logical and richer. This is my only point in discussing any of this - not to blow up STAR WARS for you, or spark controversy, but merely to provide you with a new way to look at it and, perhaps, enhance how experience it.

AN AIMLESS TEENAGER, ANXIOUS FOR BUT TERRIFIED OF HIS FUTURE

LUKE: But I was going into Tosche Station to pick up some power converters.

OWEN: You can waste time with your friends when your chores are done.

On its surface, this is a throwaway exchange between Luke Skywalker and his Uncle Owen. It’s meant to convey a sense of Luke’s relatable youth. He’s a teenager just like you in the audience, anxious for what comes next – whatever that is, of course. The future is a scary place whether you’re born in Modesto, California, Detroit, Michigan like me, or on Tatooine. Think of him as no different than any of the kids in George Lucas’s first film — and his most personal — AMERICAN GRAFFITI (1973).

But this “throwaway exchange” also tells us everything we need to know about Luke and his core priorities in A NEW HOPE (1977) and throughout its sequels, THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK (1980) and RETURN OF THE JEDI (1983).

His friends are all that matters to him.

In fact, Luke’s most important superpower across the Original Trilogy is his loyalty to his friends - not the Force.

His faith in those he cares about provides him more strength than mystical powers ever could.

But his loyalty to his friends is also his Kryptonite as they endlessly distract him from his real responsibilities (such as chores or, you know, saving the galaxy). They’re even the key to his potential undoing as we discover in THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK and the final act of RETURN OF THE JEDI.

This is because Luke lacks maturity and, more, any kind of moral core when we meet him and throughout most of the trilogy – an irony considering how he’s been held up in pop culture as such a heroic icon for decades.

It’s worth observing here that there is a deleted scene in A NEW HOPE that reinforces this problem of Luke’s and would’ve set it up as his character’s arc both in the film and greater series had it not been cut. The scene in question is part of Luke’s original introduction, which sees him hanging out with his friends — a gaggle of equally aimless kids like the one in AMERICAN GRAFFITI — and reconnecting with his best bud, Biggs Darklighter.

Biggs is briefly back home after graduating from the Imperial Academy. He confides in Luke that he’s going to defect to the Rebel Alliance. “The Rebellion is spreading and I want to be on the right side - the side I believe in.”

Luke childishly complains about how he’s stuck here on Tatooine because Uncle Owen won’t let him leave for the Academy just yet. There’s been trouble with Tusken Raiders, he says. Biggs points out that this decision isn’t one Luke’s uncle can make for him, implying Luke is just avoiding taking a position on this war (and his future).

“Luke, you're going to have to learn what seems to be important or what really is important. What good is all your uncle's work if it's taken over by the Empire?”

I’d go so far as to argue this entire exchange is the most “real” thing in all of A NEW HOPE. It’s about standing up for what’s right, avoiding being drafted into military service you disagree with, and changing the galaxy for the better. It’s about being young in America in the sixties and seventies.

But without this scene, the information we’re left to inform our understanding of Luke’s character is no less damning. And to be clear, this is how we must understand Luke, by what’s on-screen.

He’s self-involved, selfish, and utterly disinterested in anything except hanging out with his friends, going as fast as he can, and escaping his “hometown” (even though he’s too afraid to actually do it, as I’ve shown). It’s a description that could be applied to any of the characters in AMERICAN GRAFFITI, by the way - all of them teenagers on the cusp of adulthood, all of them desperate to understand what their future holds for them, and all of them scared shitless by that future.

But more problematic, Luke is even willing to join the Imperial Academy to get what he wants, suggesting he’s more than fine aligning himself with — and ultimately killing for — a tyrannical and fascist imperial superpower if it means he can get off Tatooine.

As I said, no moral core.

And without the Biggs Darklighter exchange, there isn’t even the suggestion that Luke might need to develop one. In so many ways, STAR WARS: A NEW HOPE would’ve been much better had the content of the Biggs scene — the film’s true thematic conflict — been retained.

MORE ON LUKE’S MISSING MORAL CORE

How many times have you watched STAR WARS: A NEW HOPE at this point in your life? I expect a lot if you’re reading this article. So, tell me then: when in the film or its sequels does Luke Skywalker express anything that amounts to a political opinion other than the Empire is theoretically, probably, maybe kind of bad?

Consider: when C-3PO brings up the Rebellion in the Lars homestead workshop, Luke doesn’t ask the droid about making contact with them or about how the Rebellion itself is actually going – anything to suggest he genuinely cares about its mission. He just wants to know if the droids have been in many battles.

It’s a child’s question.

Later, when Obi-Wan Kenobi tells Luke he needs his help getting the Death Star plans to the Rebel Alliance, Luke whines, “I can't get involved! I've got work to do! It's not that I like the Empire. I hate it! But there's nothing I can do about it right now. It's such a long way from here.”

Mark Hamill’s performance doesn’t help here. It sounds like a temper tantrum, reinforcing the sense that Luke has a childlike mentality.

Another way to look at this scene is: when faced with the reality of an all-powerful battle station that will kill untold numbers of people if he doesn’t act, Luke says, “Nah, I’ll sit this one out and let others fight instead. I know I won’t shut up about getting off this planet, but what I mean by all that is, to…you know…do cool shit I can Instagram about and make friends jelly with.”

Okay, it’s fair to say this is what’s required of a hero according to Joseph Campbell’s template, as this is the point where the so-called “hero” must reject his call to action. But it’s also a character trait that isn’t contradicted by anything else presented in the entire trilogy. Luke Skywalker just doesn’t care about the greater good, at least not enough to ever say so or do anything about it. He cares about what he cares about — which is his friends — and everything else can go to hell.

That is, until RETURN OF THE JEDI when Luke finally gets with the program in a way that feels organic to his — or, rather, any — character evolution. More on that later.

AN IMPRESSIONABLE YOUTH

Luke Skywalker’s lack of a moral core in A NEW HOPE and most of the Original Trilogy is part and parcel with an utterly unformed personality. I called him a child earlier, and it’s best to think of him as such – an impressionable youth.

Better yet, think of him as a super-adorable baby sponge so lacking in genuine curiosity about the universe, he unthinkingly soaks up whatever ideology you throw at him next. He really is an uneducated desert hick in this manner, so of course he buys whatever the mystic wizard with a laser-sword is selling for a few credits. After Luke agrees to join Obi-Wan Kenobi on his “damn fool crusade”, he never once questions any of the insane philosophy the old man spews. No evidence? No problemo.

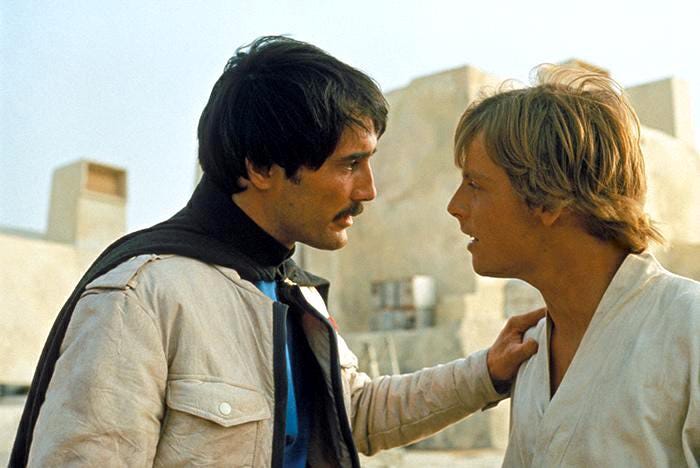

Even Han Solo can’t take the kid’s gullibility seriously.

Listen, I know this is a space opera. It’s fiction. But what we’re talking about here is a complete lack of serious character motivations beyond a concerning kind of attachment disorder. We have a kid whose only motivating force is escaping his terrible life on Tatooine to such a degree that he joins a space cult and, later, signs up for a suicide attack on a moon-sized space station just to impress a girl. Obi-Wan, Han, and Leia Organa (the girl) all end up at the receiving end of his puppy-dog loyalty for no other reason than they crossed his path.

Something else to consider is how Luke internalizes these insta-relationships:

Obi-Wan is cut in two by Darth Vader…and Luke reacts like his father died rather than some guy he just met in the desert literally two days ago.

Han is a spice smuggler who agrees to help Luke and Obi-Wan for loudly mercenary reasons…and Luke reacts to Han flying away with his credits as if his best friend has just stabbed him in the chest with a lightsaber.

Then there’s Leia, a character Luke imagines an entire identity for via a one-foot-tall hologram and the mere title of “princess”…and whom he immediately begins pining for as soon as he meets her despite not knowing a lick about her.

Things get even more problematic by the time Luke reaches Yavin 4. There is just no way to seriously explain why he agrees to join the Rebel Alliance’s suicide attack on the Death Star.

Does he believe in the Rebel Alliance now whereas before he couldn’t care less? Has he finally developed some sort of moral core at last based on anything he’s witnessed or experienced during his previous forty-eight-hour adventure? Is it out of blind obedience to his dead religious instructor or to impress the girl?

Or, does he just show up and join the party because that’s what Joseph Campbell said mythological heroes should do?

Ding-ding-ding.

It's fair to suggest this overly simplistic character work is a result of George Lucas’s general handicap when it comes to such things — he is much more of a big-picture thinker and thematic painter — but AMERICAN GRAFFITI has many young characters that feel fleshed out and believable by comparison. No, I think the bigger problem, again, is the need to make Luke comport to the hero’s journey template rather than let him drive his own actions.

FROM MOISTURE FARMER TO SUICIDE BOMBER

We should talk about the X-Wing trench run, which is thrilling and unbelievably fun and spectacularly insane from anything like a character perspective.

After joining the Rebel assault on the Death Star, Luke Skywalker steers his fighter into a kind of mechanical canyon full of deadly laser turrets to try and land a photo torpedo in a tiny exhaust vent. At this point, no more than seventy-two hours have passed since Luke, Obi-Wan, and the droids reached Mos Eisley. Luke has received maybe eight hours of religious instruction in the ways of the Force. He couldn’t even begin to explain the subject with the same level of detail found in the opening paragraph of any Wikipedia article.

What I mean is: there is no way to convincingly explain why he decides to listen to a voice in his head telling him to trust a supernatural power he didn’t know existed at the beginning of the week. Nevertheless, Luke turns off his targeting computer and puts the future of freedom in the hands of…his feelings.

First off, I know the Force works in mysterious ways. I know it’s calling to Luke in some way we’re just supposed to intuit. But Luke’s behavior before this sequence is what undermines my ability to trust it’s just the Force rather than his ongoing lack of critical thinking skills. He makes nothing but stupid decisions - and suddenly I’m supposed to think this is a smart one I should get behind?

Second, okay, sure, Luke is successful here according to the hero’s journey - but what has he accomplished as a human being that we would call the act of an actual hero?

He’s swallowed an obscure religious doctrine hook, line, and sinker without a moment’s skepticism, rescued a princess because he’s got a crush, joined a quasi-terrorist rebellion probably, mostly because he wants to get laid, and has now blown up a military superstructure, killing hundreds of thousands of people, all because he heard voices in his head. Along the way, yes, he’s made some choices, but they’re never predicated on anything like personal convictions or ideologies, serious concern for the well-being of others or a belief in any kind of greater good.

They’re instead predicated on what his friends told him to do.

Consequently, we’re left with the possibility that he does heroic (and lethal) things for unthinking, naïve, or outright immature reasons. We cheer for him despite this. So does the Rebel Alliance, which gives him a cool medal for being such a good little soldier.

THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK

Things don’t improve for Luke Skywalker by the time THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK rolls around, though the film itself does pose a significant evolution in his larger hero’s journey because this time he’s actually asked to consider the ethics of his generally erratic, still immature, and often selfish and self-destructive decisions.

When we meet Luke again, he’s now a commander in the Rebel Alliance, which feels like a bit of a vanity promotion since all he did was blow up a Death Star. It’s a few months later, and now he’s in charge of actually leading people even though he’s had no time to develop leadership skills. And his friends are still the center of his universe…including, as it turns out, the Force Ghost of Obi-Wan Kenobi who likes to haunt him and continue his training as a Jedi, or so we presume.

Obi-Wan directs Luke to go to the planet Dagobah and seek out the Jedi Master Yoda. This time around, it at least makes sense Luke listens, too, because Obi-Wan was right about “trusting the Force” to blow up the Death Star. Luke finds Yoda in short order and dives into — if my math is correct — less than forty-eight hours of Force training.

For most of this training, Luke is a great big dick, too. Unlike with Obi-Wan, he’s petulant and openly defiant with the 900-year-old Jedi. This is the same Luke who used to whine to his Uncle Owen - except now he’s super-charged with the ego of someone who singlehandedly blew up a space station.

Yoda has no patience for this kid’s attitude and immediately lays into Obi-Wan about it. “This one a long time have I watched,” he says. “All his life has he looked away - to the future, to the horizon. Never his mind on where he was. Hmm? What he was doing. Hmph. Adventure. Heh! Excitement. Heh! A Jedi craves not these things.”

In every possible way, Yoda nails Luke’s emotional shortcomings – with Jedi a euphemism for adult in this circumstance.

They’re shortcomings made all the more evident when Luke later asks, “But how am I to know the good side from the bad?” This doesn’t seem like an especially difficult question, at least not for anyone with an actual moral core.

Luke then senses a cave filled with some kind of malice. He asks Yoda what it is, and Yoda says, “That place...is strong with the dark side of the Force. A domain of evil it is. In you must go.”

So, he does. But he takes his lightsaber with him even after Yoda tells him not to do so. Again, this is meant to convey how young Luke is, how unformed he is, but the problem doesn’t resolve itself in this film.

It only gets worse.

LUKE’S FIRST ETHICAL QUANDARY

Soon after the cave, Luke has a vision of his friends in danger.

Friends, you say?

Yes, friends.

His superpower, as I told you…but also, his Kryptonite.

This leads to Luke’s first ethical quandary of the Original Trilogy, which is perplexing given the fact that the Original Trilogy is based on a reductive bifurcated view of good and evil. Luke participates in his space cult’s philosophy without ever actually being forced to make a real decision of his own. Well, that changes right now.

“Decide you must how to serve [your friends] best,” Yoda tells Luke. “If you leave now, help them you could. But you would destroy all for which they have fought and suffered.”

In other words, Luke should stay and finish his training, putting the greater good above his loyalty to his friends. This is what a real hero would do. Luke, of course, doesn’t have any of that, climbs into his X-Wing, and flies off (running away from his responsibilities again).

LUKE’S SECOND ETHICAL QUANDARY

On Cloud City, Luke Skywalker’s decision to put his friends first rather than the freedom of the galaxy comes back to bite him in the ass when his father, Darth Vader, cuts off his hand. Whoops.

Luke is then faced with his second ethical quandary of the series – join his pappy in the Dark Side or…actually, he’s not given another choice. That’s it, join the Dark Side. Luke chooses an unexpected alternative to becoming evil.

He leaps to his apparent death.

The problem is, the motivation for this act is, like so much of what Luke does…murky.

On its surface, it strikes me as very noble and sacrificing. What a heroic thing to do, right? Except Luke isn’t prone to doing anything based on any kind of personal ideology, as we’ve found time and time again. He’s never professed one except, as I keep coming back to, friendship. He’s more of a “bros before galaxy” kind of guy, I mean.

Because of this, it’s hard to understand what drives him to throw himself to his death. This isn’t to say the act itself cannot be viewed as genuinely heroic, but simply that it is not predicated on any discernible moral framework that holds his character together. We’re left to rely only upon Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey framework to explain why any of this has happened. The hero had to hero, so he hero’d, it’s really that simple.

WHY EMPIRE IS ACTUALLY SO DARK

In the aftermath of his encounter with Darth Vader, Luke Skywalker must confront the reality that Obi-Wan Kenobi lied to him about who his father really was. The Jedi, he now knows, are liars or, at least, capable of lying for their own purposes.

It’s important to recognize how necessary this is to Luke’s emotional growth beyond stunted man-child. The space cult he joined is imperfect and fallible. If its senior adherents lied about this, what else have they lied about? More, if Luke allowed himself to fall for this lie, what else has he — in his unthinking, unquestioning manner — also fallen for?

Back in A NEW HOPE, Obi-Wan told him, “You have taken your first step into a larger world.” But in hindsight, that statement feels disingenuous. Touching the Force wasn’t spiritually transformative for Luke in any way. It was, however, narratively necessary to move Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey — and George Lucas’s trilogy —forward.

The reality is, Luke’s real first step into a larger world is the realization that the power structures he has dumbly believed in so far are actually morally complicated and, thus, susceptible to moral decay and corruption. Remember, Lucas was a child of the sixties and created the Empire as an allegory for America’s slide into authoritarianism. He was as anti-establishment as they came at the time.

More than any other aspect of the film, this is why I think THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK is such a dark story. Our protagonist, our noble hero, discovers everything he naively accepted as true is a bunch of horseshit…which, when you consider it, is pretty much the story of any of us growing up and realizing the world is far more morally flexible than we initially believed it to be. It’s not all Light and Dark Side out there.

Now, it's time for Luke to become an actual adult rather than just pretend to be one.

RETURN OF THE JEDI

RETURN OF THE JEDI begins with the epic rescue of Han Solo by now full-fledged badass Luke Skywalker, who shows up wearing baller new robes, performing aerial somersaults, and swinging a brand-new green lightsaber. But this sequence, which takes up the whole first act of the film, is just more of the same from Luke. His friend is in danger, and so he puts everything else aside to save said friend.

It’s important to bear in mind here that it’s one year later when RETURN begins.

Put another way, Luke has spent a whole year of the Rebellion training and preparing for a single rescue mission. And when I say “training”, I don’t mean going back to Dagobah to study under Yoda some more. He hasn’t talked to Obi-Wan Kenobi in a year either. He’s just been on his own, running around telling everyone — including the biggest (pun intended) gangster in the galaxy — that he’s a Jedi Knight.

Wherever Luke was at the conclusion of EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, he’s clearly decided not to make any forward progress as an adult at this point. It’s almost as if he learned nothing from his mistakes in the last film. But hey, it’s also one of the coolest sequences in the entire series, so I’m not exactly complaining.

IS THERE ANYTHING LUKE CAN BELIEVE IN?

After Han Solo is safely back aboard the Millennium Falcon, Luke Skywalker finally returns to Dagobah to find out if Darth Vader really is his father. I mean, think about that. He waited a year to find out the answer to this foundational question about his whole existence. I’m not even going to begin to explain the logic of that decision when Dagobah was a mere few hours via hyperspace from Hoth last time around. Let’s just…you know…skip that point.

Anyway, Yoda tells Luke, “Yep, sorry I am, true it totally is,” then promptly croaks – but not before also telling Luke that he won’t actually become a Jedi until he confronts Vader again.

Outside Yoda’s mud hut, Luke runs into Obi-Wan Kenobi’s Force Ghost and politely goes off about being lied to about Vader killing his father. Obi-Wan gently insists he was telling the truth…well, kind of.

“Luke, you're going to find that many of the truths we cling to depend greatly on our own point of view,” the Force Ghost continues.

It’s Truth with a capital T the dead Jedi is sharing here, but it’s a brutal truth that complicates every day of our lives as adults.

Again, it’s not all Light and Dark Side out there in the real world.

Luke is then sent off by his cult to kill his father…something he insists he cannot do. Not because murder would be wrong. He clearly knows Vader needs to die for the safety of the galaxy, but he foolishly believes there is still good in his father and can save him if given half a chance.

Subsequently, Luke reunites with his friends, but it’s a short-lived team-up of the super-friends. After telling Leia Organa that she’s his sister — another of the lies/omissions Obi-Wan is guilty of — he breaks it to her that he has to face Darth Vader again. More, he must try to help their father. You see, Luke’s friend circle has expanded by this point to accommodate the transformation of his friend Leia into his sister and the introduction of a biological father into the mix.

It’s worth asking yourself who Darth Vader is in danger from. I’d suggest it’s threefold in his mind: the Emperor’s twisted machinations (call this spiritual peril), as well as both the Rebellion and the space cult Luke equally serves (physical peril).

What this means is, Luke has now pitted himself against the whole galaxy in an effort to save a genocidal supervillain.

Family is hard.

LUKE’S THIRD (AND FINAL) ETHICAL QUANDARY

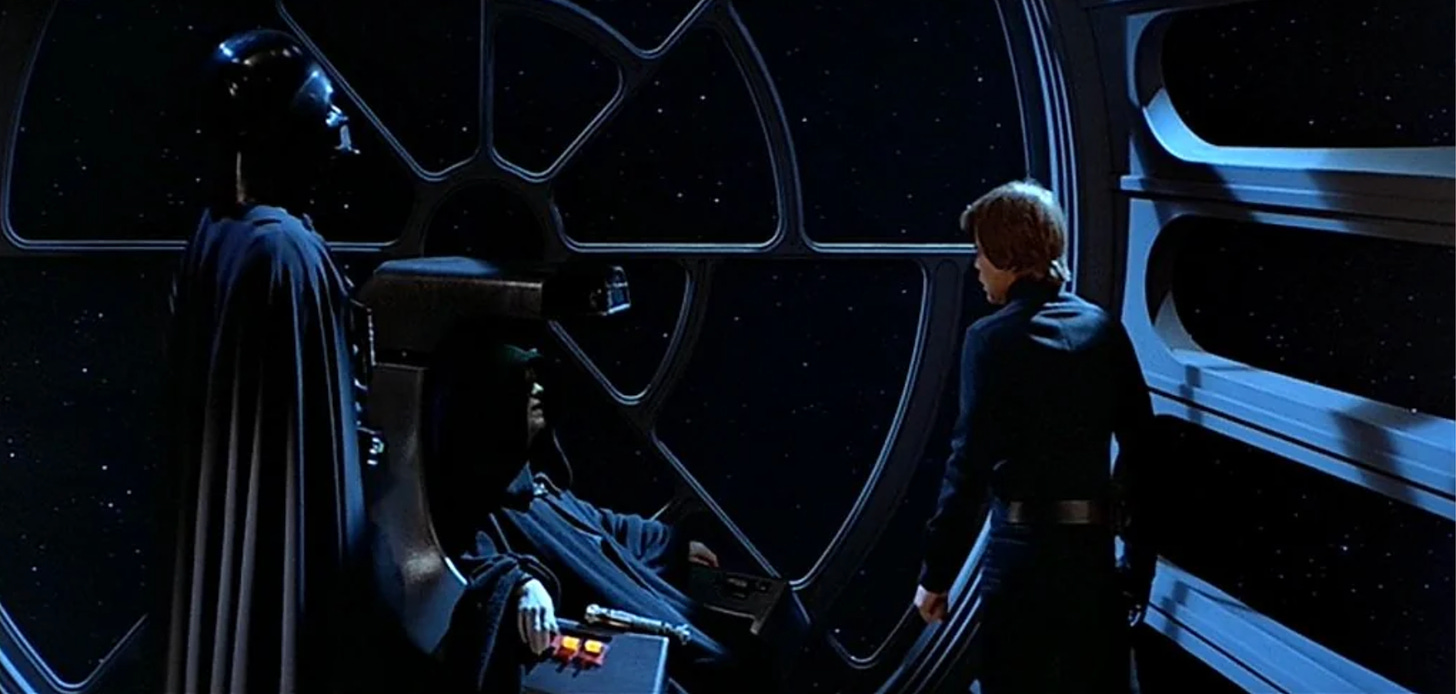

Consider this exchange on the Death Star between Luke and the Emperor:

LUKE: You're wrong. Soon I'll be dead...and you with me.

The Emperor laughs.

EMPEROR: Perhaps you refer to the imminent attack of your Rebel fleet.

Luke looks up sharply.

EMPEROR (CONT’D): Yes...I assure you we are quite safe from your friends here.

Vader looks at Luke.

LUKE: Your overconfidence is your weakness.

EMPEROR: Your faith in your friends is yours.

Okay, a few things here (besides how beautifully economical the action descriptions are here):

First, Luke showed up assuming he isn’t leaving alive. It’s another suicide run for him — his third, in fact — and I’m now beginning to wonder if this kid just wants to die.

Second, the Emperor’s final line here: “Your faith in your friends is yours.”

He outright says that Luke’s Kryptonite is his friends, what I’ve been saying all along here. It’s even what the Emperor uses to get Luke to give in to the Dark Side and attack him.

EMPEROR: The Alliance will die...as will your friends.

Luke can resist no longer. The lightsaber flies into his hand. He ignites it in an instant and swings at the Emperor. Vader's lightsaber flashes into view, blocking Luke's blow before it can reach the Emperor. The two blades spark at contact. Luke turns to fight his father.

Matters only get worse as Luke battles Darth Vader because Vader gets into Luke’s head and discovers the truth about Leia Organa’s parentage. The danger to Leia morphs Luke into a savage, lightsaber-swinging monster who, fueled by John Williams’ terrifying score, beats back his father, knocks him down, and ultimately hacks off his hand.

But it’s at this moment that Luke sees what he’s done, how he’s touched the Dark Side, and decides to throw away his lightsaber even if that means he’ll die. Unlike the conclusion of EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, which saw Luke similarly choose death over spiritual decay, his decision here makes absolute sense based on the journey he took to get here.

He is at last a Jedi like his father before him.

Moments later, Vader, overwhelmed by the sight of his son on the verge of death, lifts the screeching Emperor over his head and hurls him into the Death Star’s bowels.

YES, THE ORIGINAL TRILOGY IS A HERO’S JOURNEY…BUT NOT IN THE WAY YOU PROBABLY THINK IT IS

If you’ve read this far, you might assume I don’t fanatically love STAR WARS: THE Original Trilogy. You would be wrong there. I do, and it’s a love affair that has pretty much spanned and enriched my entire life. But that doesn’t mean I, as a storyteller, am not interested in exploring the tension between George Lucas’s intentional creative engineering and the deeply personal coming-of-age story he ultimately showed himself to be much more interested in telling. The unintentional alchemical reaction produced by the interplay of this tension is why I believe STAR WARS has endured for nearly fifty years.

More specifically, it defines the thematic journey and resolution of the series.

Maybe I should remind you how Joseph Campbell’s monomyth plays out. It concludes with the hero acquiring “the ultimate boon”. This is the achievement of the goal of the quest – what they went on their journey of enlightenment to get in the first place. The hero must then return changed, transformed somehow by “secret knowledge”, and then change his world with it.

In the Original Trilogy, Luke’s apparent goal, if he has one at all, is to become a Jedi like his father before him. But that’s his perceived goal. You could say it’s actually saving the galaxy, but, again, he never states a political belief or expresses a deeply held moral position that defines his actions above all others. If anything, he spends most of his time acting like that isn’t even a priority for him, often even complicating that larger mission through endless selfish rather than selfless decisions. No, becoming a Jedi — and keeping his friends safe — are his only real commitments.

But Luke’s true goal, the one that Lucas is far more concerned with from the character’s introduction in A NEW HOPE, is to acquire a different kind of secret knowledge – maturity.

Luke Skywalker must grow up.

At the conclusion of RETURN OF THE JEDI, Luke fulfills his forced obligations to Campbell’s hero’s journey. He returns changed – check. He has been transformed by a secret knowledge – check. And he changes his world with it – check.

But what is “his world” in this case?

The Jedi Order.

He’s resurrected it with a new kind of moral core based not on the old ways of the Jedi, but on the maturity he’s gained from a series of immature mistakes he barely survived and the discovery that even the alleged good guys are liars. The future of the Jedi will be shaped in response to an establishment he no longer agrees with.

Luke is the future now…as we all must eventually become.

IN CONCLUSION

Yes, STAR WARS: THE ORIGINAL TRILOGY is a hero’s journey as defined by Joseph Campbell, but most of the time that journey is in deep conflict with the emotional journey the actual “hero” seems to be on. This is especially evident in A NEW HOPE, where Luke lacks motivation for pretty much every decision he makes (which has always, I’ll add just for kicks, made it easy to project whatever motivation you want on to him). But over the course of the trilogy, Lucas’s own anti-establishment views eventually redefine Luke’s emotional journey, making it a deeply personal coming-of-age story for the filmmaker. By the trilogy’s conclusion, the traditional hero’s journey template is hijacked by a far more universal — and simpler — story of a kid finding out how to live in a world that doesn’t live up to his childhood understanding and expectations of it.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, you might also find something of value in these:

Love it! Had no idea about that deleted scene and yes it would change SO much. Really enjoying reading your work!

Star Wars has never been the "hero's journey" that Lucas claimed it to be. (And that's OK.)