The Three Burials of Some Assh@le Named Cole Haddon

A trilogy of screenwriting horror stories about what can happen when you expect Hollywood agents to keep their promises

1.

The first time it happened, I had only been represented by the agency for a few months.

When I signed with my new team of super-agents, a whole host of them promising to turn all my myriad creative ambitions into a fortune, I asked them to agree to three rules if they wanted to get into business with me.

One, I was only interested in pursuing prestige television projects going forward. Which meant no more network.

Two, I wasn’t interested in pursuing any opportunities that would result in a TV season longer than thirteen episodes. Which, at the time, meant no more network.

Three, they had to make sure I never got into business with anyone like the dreaded Mr. Smiley, my producer on “DRACULA”, ever again.

Everyone said, “Great, love it, love you, let’s do this!”

I then informed the other four agencies I’d met with that I would unfortunately not be signing with them, but I appreciated their time and consideration.

Three months later, I got a call from my new agency. There was a CW project my senior TV agent wanted me to consider.

“But you know I don’t want to do network,” I told them, confused.

The agent asked that I just look at it. I did. It was a spin-off to a series I wouldn’t watch if there was nothing else on television that night. “Thanks,” I said, “but it’s not for me.”

My agent advised me to take the meeting, implying it would be a favor to them. I’m a team player, or like to think I am, so I reluctantly took the meeting. I quickly discovered the project was not just a network series, but it would’ve also required me to showrun more than twenty episodes in a year.

I called my agent back afterward. “It’s still a pass.”

The agent’s voice changed. Their patience had been spent. “Cole, this is a great opportunity.”

“I told you when you signed me, I wouldn’t do network and I wouldn’t create or showrun anything that was more than thirteen episodes long,” I reminded them.

“Everybody says stuff like that when we sign them,” they told me. “Then, we tell them to take the money. Take the money, Cole.”

I did not take the money. My TV agent never got on the phone with me or replied to an email from me again. Our relationship was over, though every year afterward for close to a decade, I inexplicably received a Christmas card from them.

2.

The second time it happened, I signed with an agency that made me three promises:

One, they would fully support my decision to move to the United Kingdom and help me build an international career between Hollywood and Europe. This was necessary because after the 2016 election, my wife and I had decided to leave America. It was time to start over abroad, but I wanted to continue to build on my career in the States. After all the effort I’d already put into it, it seemed insane to abandon it completely.

Two, they had a U.K.-based agent that would represent me there and help facilitate projects between the U.K. and Hollywood. I was going to develop “international TV series” now, or so was the pitch.

Three, I would be represented by senior partners in both film and television – TV being the most important as it had become my primary bread and butter since “DRACULA”. The market had changed, and I had changed with it.

One week later, I contacted my manager and asked why my TV agent wasn’t responding to emails or returning my calls. Over the next two weeks, the situation did not improve.

My manager spoke to the agent, who apologized. Things in their life had gotten out of hand, they said. The agent then called me and similarly apologized. “Let’s do a quick reset,” they suggested; don’t worry, I was told, they were on it.

Two weeks later, every email and phone call from me and my manager had once again been ignored. I had been their client for four weeks, usually the period when agents are most gung-ho to “get you out there” and make something happen, and instead I’d been ghosted.

By the agent who had literally just signed me.

I had no time left to deal with this in the States. I was on my way to the U.K. and reasoned my manager and I would work out a solution soon enough. For example, maybe another agent at the agency more keen to represent me.

But when I got to London, the situation became much, much worse.

I quickly discovered the U.K.-based agent I was promised was not actually a U.K. agent. They were some kind of variant of an agent tasked with finding U.K. talent to sign and get work in the States. In fact, they had no legal standing to even represent clients in the U.K. Nevertheless, they decided to set a slew of introductory meetings for me. Each was worse than the one before, it seemed, until I discovered one development executive I was told to meet with was actually in business affairs. I have no idea why I was told to meet with this person.

Now I was panicking. I had moved across the world presuming I had a team of agents in place to help me make this transition, but most of that team of agents had turned out to be imaginary. When I spoke to the agents who did pick up their phones, they sighed a lot and couldn’t explain why my TV agent had written me off. I asked if they could get me another TV agent, but was told that was internally complicated, so they, my film agents, would just rep me for TV instead. Which is just about the stupidest thing an agent has ever suggested to me in this business, and I’ve heard a lot of stupid shit.

When I left the agency, mere months after signing with it, I was low-key screamed at and made to feel as if I was being unreasonable expecting the agency to live up to even one of its promises.

3.

The third time it happened I was newly signed with the U.S. agency that replaced the “team” I just described.

After much fanfare around my moving to the agency – including a press release that revealed to the world the existence of a top-secret project I’d sold, enraging its producers and my employer – I got a call from my TV agent who told me they had an exciting project for me to consider. It was a passion project of theirs. “Ooh, tell me more,” right?

I was sent a novel and was asked to consider adapting it for television.

I then read this novel, which I found…enh…okay. But because it was my agent’s alleged passion project, I had to tread carefully. I told them how much I enjoyed it.

“I have some thoughts, but it's a very exciting opportunity (cough- bullshit-cough).”

Then, my agent explained there was a pilot script already. Now I was confused. There was a script?

Yep, another client had written one on spec. This, I said, concerned me. I didn’t want to steal another writer’s project.

Oh no, I was told. I wouldn’t be stealing, I would be rewriting.

“I’m sorry, what?”

My agent didn’t want me to adapt the book myself. They wanted me to come onto the project as a co-creator, fix a new writer’s problematic script on spec, and then showrun it.

“But I don’t co-create,” I said slowly, panic already tugging at my voice. “I don’t co-write. I do my own thing.”

The agent grew increasingly frustrated and annoyed as it became clear I wasn’t going to do free work on someone else’s project I didn’t even think was a strong premise for a TV series anyway. Somehow, I was in the same situation I was way back when I turned down that CW project. My agent expected me to do what they told me to do and I, in saying no for completely legitimate reasons that wouldn’t have surprised anyone who’d spent five minutes with me talking about my career, was ending that relationship.

Which is exactly what happened.

After I hung up the phone, I never heard from the agent again in any form.

All of these stories took place over a five-year period after my TV series “DRACULA” was cancelled. In the first two instances, I had passed on numerous other agencies and management companies that had wanted to sign me instead. But you can’t go back to someone after you told them they weren’t your first choice, even if it’s to say, “You don’t understand, the other guys lied to me!”

In other words, by the time I signed with the third agency in this story, I had few alternatives left anyway. Especially not with a reputation for being “hard to represent” because, in part, of the shenanigans at the first two. I had become the kind of writer “life was too short” to work with.

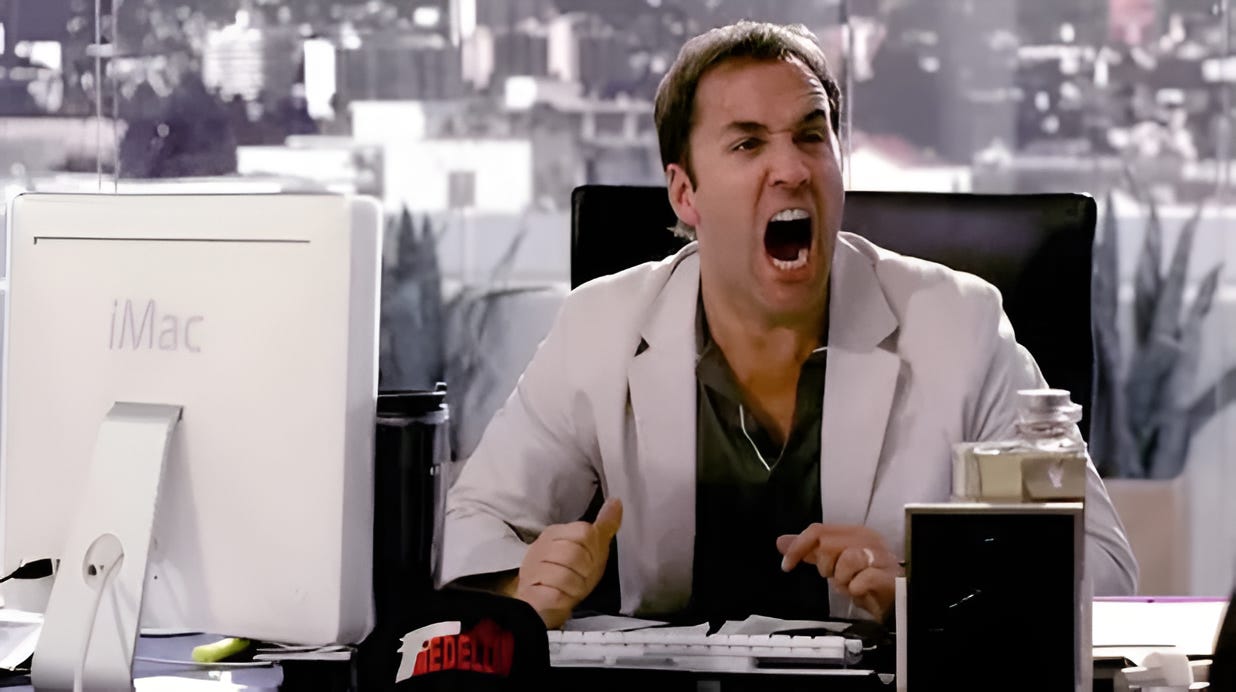

In the years since all this went down, I’ve had other American representatives. The experiences have rarely been much better. My mental health suffered from it to such a degree that I would grow agitated for up to twenty-four hours before I was due to hop on the phone with one.

You know how you have to be careful with a feral dog or cat that expresses interest in you? It gets close, curious about you, and you tense up even though you want to play with it. You change your voice, you don’t make any sudden movements, you try to inspire the animal with your own excitement…because you know, despite how much you like animals, it could bite your face off at the drop of a hat. And when it’s over, you can’t help but notice a sense of relief it didn’t go wrong.

That’s what it was like for me dealing with U.S. agents (albeit with a few exceptions I still call friends). So, I just stopped instead. I now rely entirely on my U.K. to handle my film and TV business. I’ve never dreaded a phone call from any of them, nor do I think I ever will. All of them express confusion that anyone could ever find me difficult to work with.

At the end of the day, I’m still here despite these three stories of agency abuse (or whatever euphemism for that I should probably refer to it as)…but only because I refused to let the bastards bury me.

A career in the arts means you will inevitably have to develop business relationships with people who see you as nothing but a number on a spreadsheet. To very few of them are you an actual human being with things like a pulse, emotions, or bills to pay. The trick when it comes to the Hollywood variety of agents as partners — that is, if there is one to master (and I don’t know if I ever have) — is to somehow never say no to them, never make them feel like you know more than them about anything, and to make sure every idea you have is one they can take credit for. Or better yet, just avoid them, if at all possible.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

The F@cked-Up Amount of Free Work It Takes to (Not) Sell Something in Hollywood Today

When I sold my first feature screenplay in 2008, all that was required of me was a solid logline and a rambling, generally unfocused fifteen-minute conversation inspired by notes I had scribbled down the day before. Other projects I sold in the late aughts and early teens involved no more than a five-minute reply to that classi…

Every Screenwriter Dreams of Creating a TV Series...But What Happens When You Can't Bear to Watch the End Result?

This article is part of 5AM StoryTalk’s celebration of the complete and utter shitshow that was 'DRACULA' (2013) on its 10th anniversary. The TV series, which I created for NBC and Sky, remains the most painful creative experience of my career because of elements within the production. You can read more about its development and greenlight in

Why You Shouldn't Trust Hollywood Talent Agents

So, here’s the thing: there are a lot of amazing agents in Hollywood. But here’s the other thing: there are a lot more terrible ones. From my experience, this is a cultural/institutional problem, in which agencies attract smart people who want to work in the …

Ooofff. I always wondered if I might have been more at home with the industry abroad, approximately 200 yrs ago

Subscribed! And so happy to have found your Substack. ♥️🙏🏽 Funny (not really), a while ago a took a bunch of (LA) meetings for a pilot I wrote that did well on The Blacklist. I was told the writing was fantastic, etc, but there was no way a Korean (or Asian) woman could carry a dark comedy. 🤷🏻♀️ This was right before Killing Eve. It really c*ntpunted me for a long time. Only recently began writing again but am way more drawn to international TV since living in Europe the past few years after that aforementioned c*ntpunt. I look forward to learning from - and following - your journey. Thank you for putting it out there.