Why You Shouldn't Trust Hollywood Talent Agents

They're not all bad, but let's talk about their institutional inability to be honest with clients (with one hell of an example from my own career)

So, here’s the thing: there are a lot of amazing agents in Hollywood.

But here’s the other thing: there are a lot more terrible ones.

From my experience, this is a cultural/institutional problem, in which agencies attract smart people who want to work in the entertainment business and then slowly, methodically corrupt them and turn them into assholes in expensive clothes incapable of ever being entirely truthful to their clients because their two greatest objectives – preserving their position and maintaining the rep-client power-balance (the illusion they know everything and everyone and you do not, thus you cannot survive without them) – make being so a professional risk.

For example, I once asked my former agent what they thought about me rebooting a comic book property for television after its feature adaptation fell flat several years before. The agent told me they were looking into the situation at the studio, which I followed up on several times over three months until said agent, realizing my query wouldn’t go away, finally admitted they had never read the comic book or seen the film despite saying they knew it well. Consequently, they hadn’t even bothered to approach the studio about it. Now, this agent could’ve simply said this upfront, but the fear of admitting they didn’t know something was too much for them. Lying and hoping I’d just forget about it made far more sense to them - and this wasn’t even about anything important.

Today, let’s discuss one of the most egregious examples of representatives deceiving me — this time about something genuinely serious — and what you can learn from it.

The set-up: I get a call from a producer I respect. They ask me if I’m a fan of Director X, whom I will not name, but let’s just say they’re one of the biggest international filmmakers in the world, feted wherever they go, and absofuckinglutely I’m a fan of them, I quickly declare.

That’s good because the producer has a project with Director X, and the producer thinks I’d be perfect for it. After I pick my jaw up off the floor, things progress quickly and I find myself attached to adapt a novel for Director X. We’ll take it out to the town as a pitch, but first, given how much talent loves Director X, we’ll go out to actors first.

A few names come up, but we settle on Brock Rockwell. No, not the actor I recently described in “Screenwriting Tales: The F@cked-Up Amount of Free Work It Takes to (Not) Sell Something in Hollywood Today”. I’ve just decided I love this ridiculous name and will now use it for every leading man I talk about in these stories but am unwilling to specifically name because I don’t want to burn the wrong bridges or get sued.

Brock is sent the material by my agents who, I should add, work at the same agency as Director X’s. It’s a team effort, and I’m assured this is going to make a huge, splashy deal. “You’re getting a movie made, just don’t mess it up,” I’m told multiple times in multiple iterations.

These agents soon inform us that Brock is wildly interested, as he’s a huge fan of Director X. I’m told they’re just going to hash out the details with his team. He wants to meet Director X, too.

High fives all around. “Yeah, bro!”

I don’t actually say this: “Yeah, bro!”

But it’s the kind of thing you heard a lot at agencies before they began to hire more than the handful of women that they used to use to avoid accusations of being misogynistic frat houses full of Ari Gold wannabes. (Note: This half-assed effort did not work, as nobody ever mistook agencies as being anything other than boys’ clubs until more recently).

Anyway, back to my tale…

This has all been so easy, I think — being Director X’s pick, landing Brock Rockwell — I can’t believe it. But I’ve worked hard and tell myself this is what all that hard work was always going to eventually get me.

A couple of months pass.

Any attempts to get my agents to update me about what’s going on gets some version of, “We’re working on it. These things take time.”

Sure, that makes sense…right?

A couple more months go by.

Everyone on the project wants to go pitch this, but we don’t have a star yet even though we were told we have a star. Do we not have a star after all? Who knows? My agents certainly won’t say.

This is all confusing and, with every deflected question, increasingly infuriating.

Director X can get us any meeting we want, so, with the producers, we decide to take a few while our agents continue to work on Brock. Better to play it safe.

It’s now two weeks until Director X and I have to pitch this project to buyers.

Director X is flying in for it between shoots, so it’s a whole affair. My agents keep insisting I need to calm down, as I’m sending daily emails at this point trying to work out what’s happening (or not happening). They’re working on Brock, they insist. They’ll make it happen, bro.

It’s now a week out.

Still no Brock.

I email my agents and outright tell them they need to stop “pretending to be agents” and get this done. I’m told I need to get control of myself.

But I’m desperate and don’t understand why any of this is happening.

I call a good friend of mine who happens to also be friends with Brock. “Listen, I would never ask this if it wasn’t such a big deal for my career. Can you just text Brock and ask him if he’s ever heard of this project?” I ask.

Ten minutes later, I get a call back: Brock has never even heard of the project.

My agents and Director X’s agents have apparently been lying to us the whole time.

None of us can explain why.

Maybe the best explanation is that Brock is represented by a rival agency and our agents didn’t want to facilitate that. But if this is true, bear in mind that it means these agents were willing to kneecap deals for two of their clients, deals that would have been astronomically larger with such an attachment, just to avoid involving a rival agency’s client with the project.

A week later, Director X, producer, and I sell the project in the room. No star attached. My agents never discuss Brock Rockwell with me again and another party involved warns me to let it go if I know what’s good for my career.

At the end of the day, I never got to the bottom of why my agents spent months telling me an A-list actor wanted to attach himself to my project. Maybe it was one agent who deceived the others, maybe it was all of them colluding.

So, what can you learn from all this? That’s why you’re reading, right? Or are you here to gasp at my professional horror stories the way you do a car wreck you can’t look away from?

Don’t worry, I understand. I have a lot of these and the only way to make sense of them today is by sharing them with you. Hopefully, you take something from them that helps you in some way, that makes you feel less alone in this crazy business, or just entertains you.

First, the key takeaway is agents can be great people but the profession generally makes them poor business partners. There are exceptions, yes, but you should – at least from my vast experience with agents, in particular – always demonstrate a healthy degree of wariness.

Second, always trust your gut when you think someone is lying to you in this business. The more they assure you everything is okay when you voice concern, the worse that typically means the lie is.

Third – and this is incredibly important – lean on your lawyers if you have them. They have an obligation to only speak the truth to you and can often point you in the right direction even if they’re not directly involved in the conversations being had. In the case of the months-long Brock Rockwell lie, I only came to understand the potential conflict at my agency over attaching a rival agency’s client through my lawyer’s counsel on the matter. (On a future occasion, I’ll write about negotiations and why you should never agree to any deal with your agents until you’ve privately spoken with your lawyers.)

As for how things played out with my agents after all this happened?

Well, I wasn’t repped by the agency within a couple of months of my sale - no doubt because of the “you need to stop pretending to be agents” email. It’s a professional relationship I’ve never mourned because I have no idea how any client could ever trust their reps again after a deceit of this magnitude.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

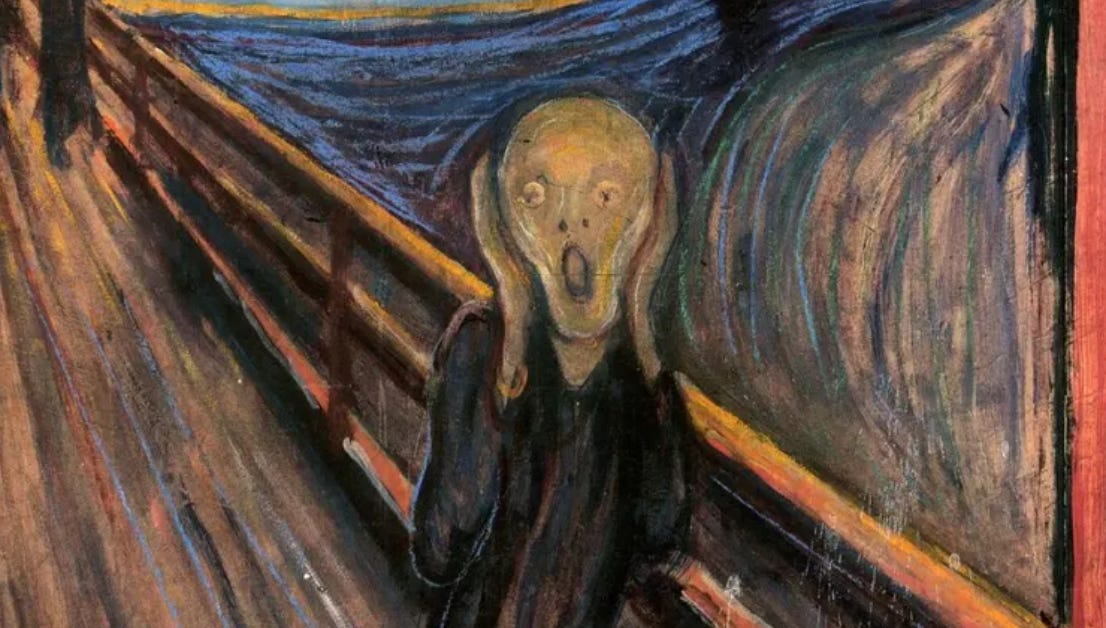

That might be the best use of The Scream I've seen.

Thanks for the play-by-play of EXACTLY how CAA (and WME, ICM, UTA, Paradigm, et al) operates (been there, done that). When your project is a home run for them, it's good for you. When it's "just another one of your ideas," or when you become "older than most of our clients," you're invisible. That's why I sued them and won.