The Problem with How We Write (and Think) About Location

Okay, it's not so much a problem as a problematic lack of acknowledgment of the role that readers often play in the stories we tell

Back in the ’90s, I dipped my toe into the world of independent filmmaking in Michigan. I’m not going to get into what that entailed, mostly because so much of that period of my life is a blur, but there is one memory that stands out and will be relevant to what I want to discuss here today. I paid a visit to the Michigan Film Office. Today, its name seems to have evolved into the Michigan Film & Digital Media Office. Sounds fancy. It wasn’t thirty years ago, that’s for sure. During my sit-down with its head, she received a phone call from someone curious about filming in Detroit. She was curt, then hung up and told me some version of, “This happens all the time. People call. ‘We’re shooting a post-apocalyptic movie and we hear you have deer running through abandoned buildings in Detroit.’ I tell them they’re crazy and hang up.” When I pointed out I’ve heard the same thing, this person admitted, “Well, of course there are. But I don’t want anyone else to know that. That’s not how I want people seeing Detroit.”

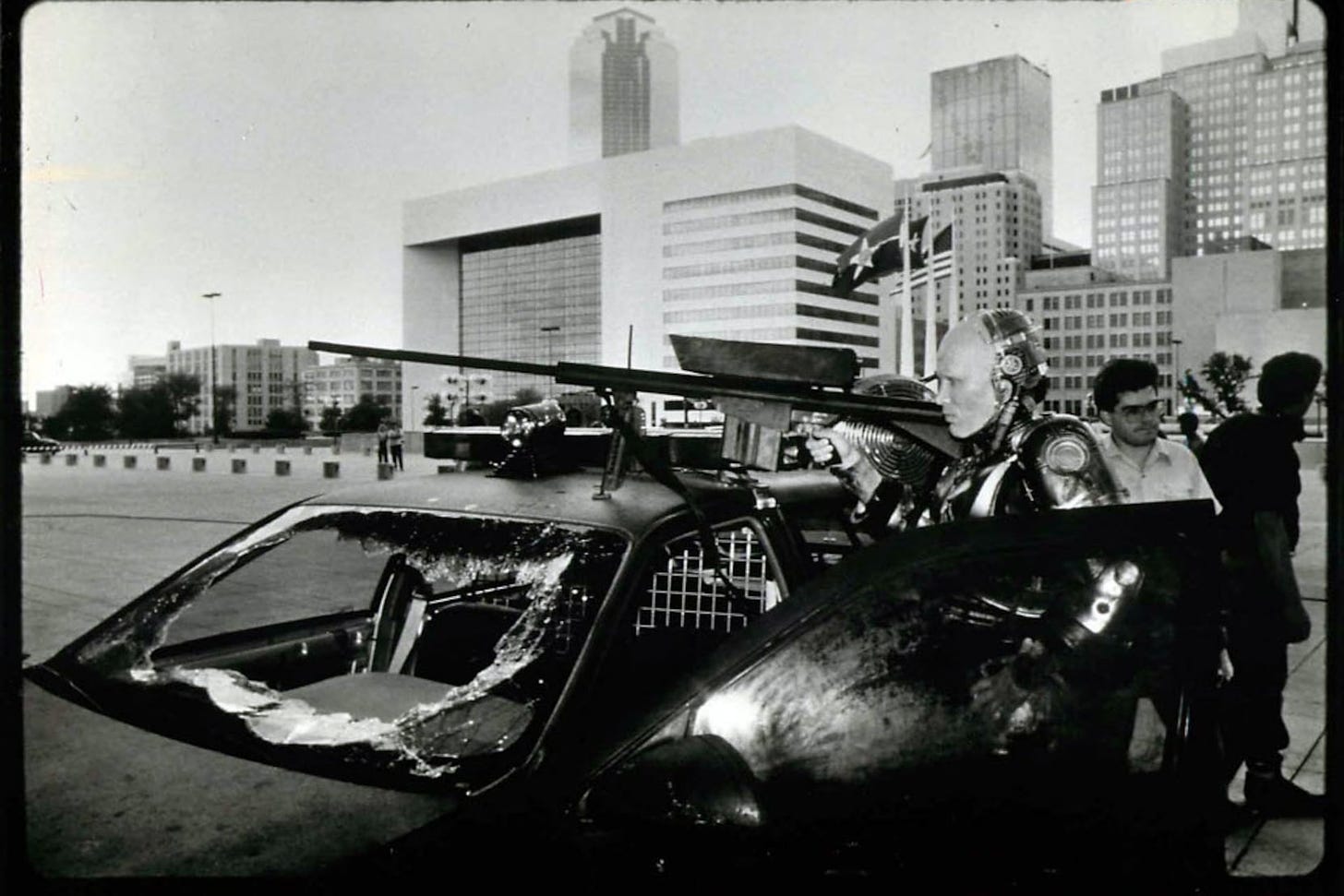

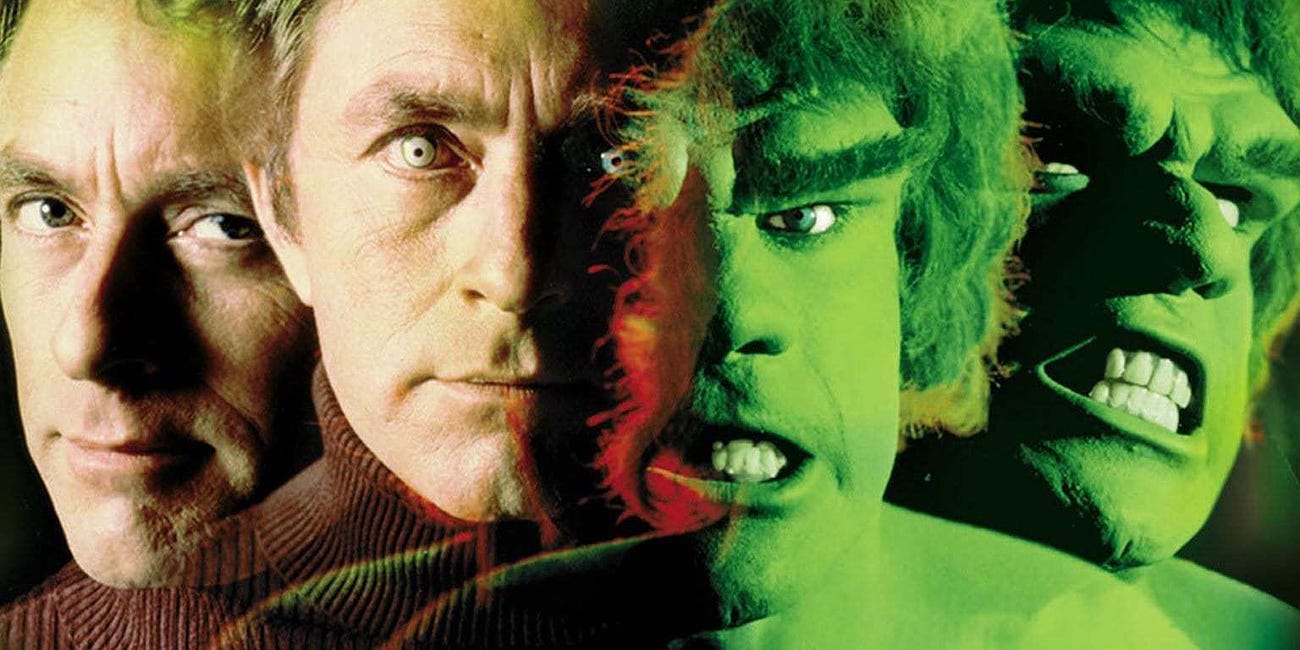

Here's another story for you, from my early days in Los Angeles. Probably 2006. I got into it once with an emerging Texas filmmaker who couldn’t stop shitting all over Detroit, where I’m from – a city I love very much, by the way. This filmmaker pointed his finger at Robocop (1987), which is set in Detroit, as proof of what an ugly, half-ruined hellhole the place is.

In a screenplay, this is where you insert the parenthetical (beat).

“But Robocop was shot in Dallas,” I replied.

Location is a powerful aspect of any stories we tell, both the ones about ourselves that we share with our families and friends and the ones we tell on page, on screen, and elsewhere. We’re told to bring these places to life through details, details, details. Typically, these details are technical. Myself, I prefer to find ways to do so emotionally, connecting foreign places to my readers through their own lives. What I mean is, every location is unique, but quite often the way we experience them is universal. Finding that balance between specificity and shared emotional pasts/truths is part of the process, I find, or at least mine. Readers of Stephen King — whom I’ve been rereading a lot lately — will recognize this is a defining characteristic of his writing.

But all this said, there’s another way that location can be defined, too. And that’s based on the reader’s assumptions about said location that were acquired by way of other media – such as my anecdote about Robocop.

This requires a bit more example-giving, I think.

In the ’90s, the vast majority of Americans’ knowledge about Detroit was based on two things – the nightly news regularly remind them that it was the murder capital of the country and the shitty state of the place as depicted in Beverly Hills Cop in 1984. Four years later, Robocop only confirmed this image of the city for these Americans - a violent, blood-soaked, collapsing dump. Racism obviously played a part in all these ideas, but that’s a conversation for another day.

By the time Out of Sight was released in 1998 –a significant part of which is set in Detroit – there wasn’t anything about its (yes grimy, but also) beautiful portrayal of the city’s history, architecture, and distinct urban character that could erase the damage that had been done by the nightly news and other films. Watch it today, and it’s still difficult to separate what you think about Detroit from the reality of Detroit as shot by director Steven Soderberg and his DP Elliot Davis. Thanks to all those earlier, ugly images, thermal steam escaping from manhole covers on a wintry day can’t help but look “ghetto” rather than the uniquely poetic feature of the city that it is. In fact, very little onscreen since the ’90s has done much to rehabilitate how pop culture still thinks and talks about Detroit today.

What I’m trying to get at here is this: your reader isn’t always just going to be responding to your words regarding a place fixed in both space and time. They’re very often going to bring their own ideas about it, their own biases, their own erroneous history.

Now, I suspect there are writers who don’t want to take this into consideration. In fact, I know there are because I’ve been told by many of them that they cannot write with the audience as part of their process. Including the reader, incorporating them into the experience in some way, can feel unnatural and wrong to many artists. If we do so, we’re allegedly ceding our artistic integrity in some way, corrupting the process, ruining the purity of our art. I get it and I don’t argue with anyone else’s approach.

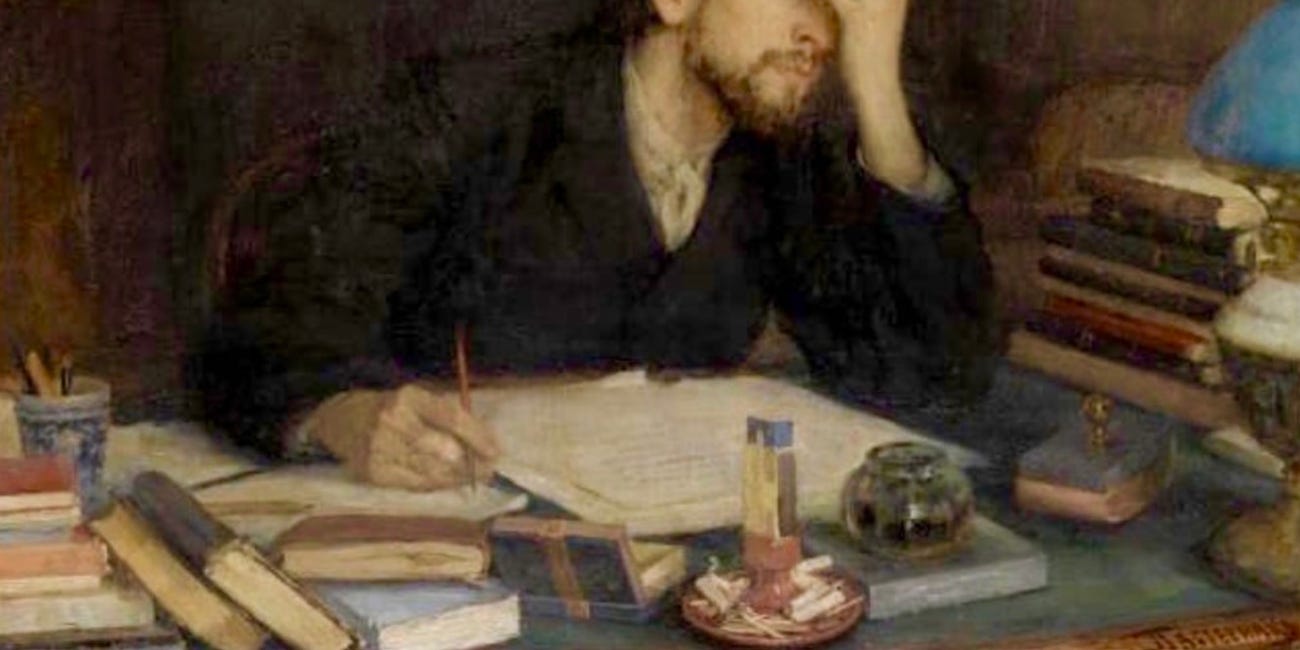

But for me, there is no getting around the fact that our audiences exist. A painting isn’t just a painting, after all. It requires a viewer, someone to move around in front of it and “converse” with the composition, someone who is also quite often the target of the image itself. As Ansel Adams said of photography, “There are always two people in every picture: the photographer and the viewer.”

I believe novels, films and TV, and comic books are no different.

Which is why I choose to engage with my readers’ knowledge of, but also misunderstandings about a place (or a time). For example, in my debut novel Psalms for the End of the World, I described numerous locations I had visited, many of which I had come to love. I had studied many of these extensively. But as I worked, I knew others didn’t have the same knowledge of them. More often than not, they would have ideas about these locations based instead on things they’d seen on the news, or in a docuseries, or, more likely, a film or TV series. Some of these ideas are technical, factual you might say; some of them are purely romantic. Was I supposed to pretend this away? (In Psalms, art has a reciprocal relationship with the dimensions of reality, so it also in some ways served the story - but this is too difficult to explain here and, more, would ruin aspects of the novel for potential readers.)

Consider: Everyone thinks they know what both Rome and Ancient Rome look and feel like, but in the case of the former, very few of Earth’s residents have actually visited Rome and, in the case of the latter, even Romans today have very faulty understanding of the city’s deepest history and daily way of life (not that I am a master of any of it). What this means is, if you leave blanks in your text, readers will fill them in. Hell, they’ll crawl in between words and fill in non-blanks, too, whether you like it or not. Readers cannot unknow something they think they know, no matter how great your writing is or how it seeks to serve as a corrective.

Consequently, I prefer to incorporate the reader into the narrative experience. I don’t pretend away what pop culture has done to popular understandings of locations (and history). I count on it. Very often, I even use it against the reader to surprise and challenge them and subvert their expectations.

These observations might not seem immediately actionable, but I believe it is. You have to ask yourself two questions to start:

What do I think I know about Location X?

What does the reader think they know about location X?

The distance between the two is important to measure, I think. If it’s vast, you either have a lot of work to do or a lot of opportunities to play on the readers’ expectations of the place – for better or worse.

Maybe my best example I can provide about this is Hallmark Christmas films.

Yes, Hallmark Christmas films.

Every single one is set in the same collection of locations even though the location names change with every film. No aspect of these locations has to be established anymore. They simple are. We the audience have preconceived ideas about what each of them are, and the filmmakers anticipate that. If Hallmark deviates from these preconceived ideas, it’s immediately noticeable — even startling — to its audiences. In this case, such deviation suggests opportunity for exciting interplay with people tuning in at home. You can use their expectations against them, to confuse them, to surprise them, to thrill them.

Now, do the same with what audiences might think about your quaint English village, or your Midwestern American suburb, or the “tropical paradise” you call home. See what I mean?

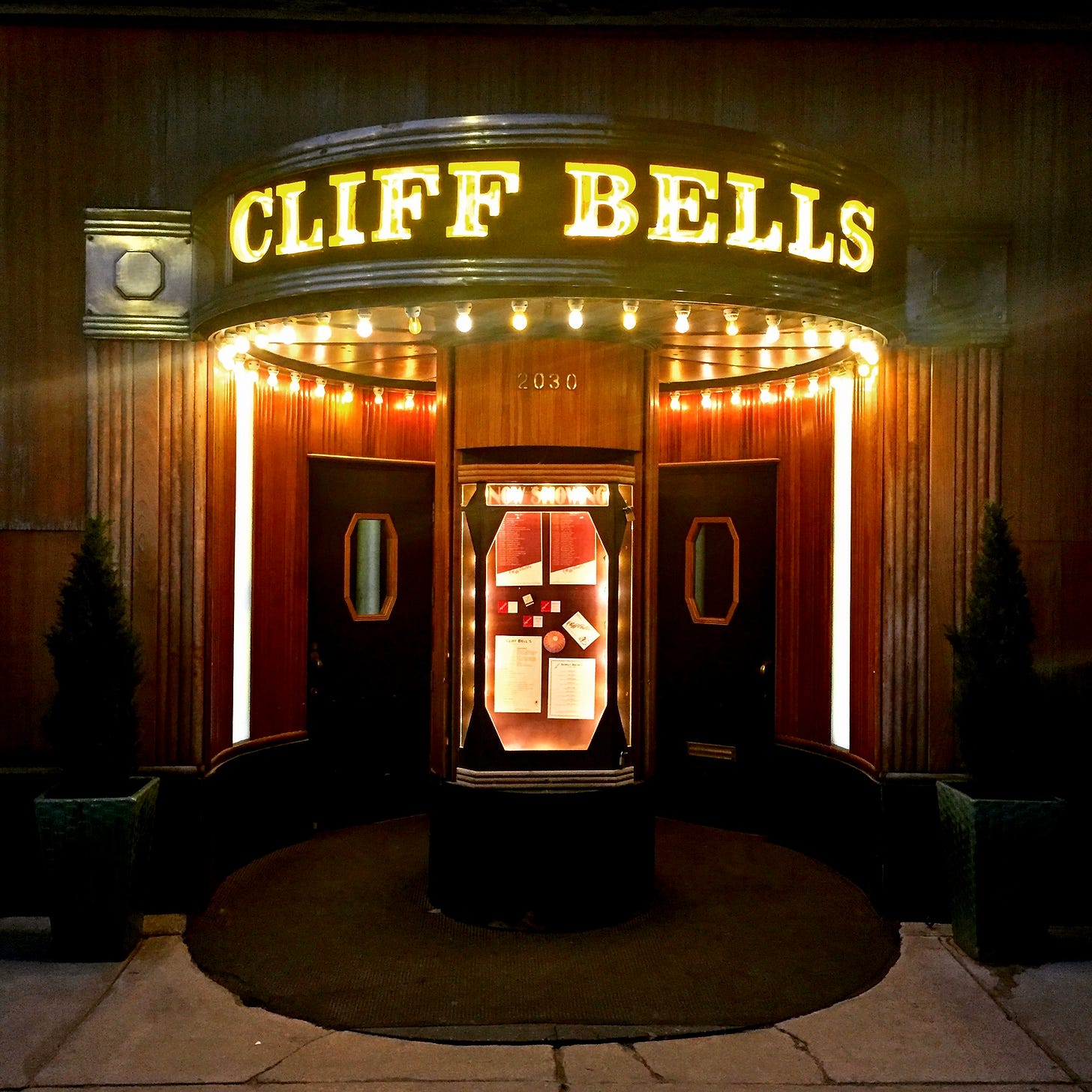

I’m going to close today by sharing some photographs of Detroit I’ve taken over the years. If for no other reason than it’s a location near and dear to my heart. Maybe some of these pics will challenge your own ideas of the place. I find pointing a camera at thing helps reveal how I truly feel about it, and typically only then do I feel wholly comfortable writing about the place. In fact, I’m writing about Detroit and the suburbs that grew up around it right now - it’s my first time “going home” on the page!

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

This is an important post for me because I am from New Mexico, and grew up outside Albuquerque, NM. Now, people don't believe it these days, but previous to Breaking Bad it was very, very, VERY common to run across Americans who did not know that New Mexico was a state. This was regardless of where they were from. I had cousins, related to me, that did not know their kin lived in a state.

I tell people that today and they literally are like "I mean I always knew New Mexico was a state" but no they didn't. I grew up taking road trips to people asking me how I was white, how I spoke English so well, did I need a passport to enter the US? Even to this day, after I tell people where I'm from, most of the time their brain defaults to Arizona. They remember me saying I'm from a Southwestern state, I guess they figure "I would have remembered if it were Texas, sooo... Arizona?"

Anyway, this is all to say, New Mexico and Albuquerque specifically have sort of a history regarding representation on television. Namely that the reality show COPS caused Albuquerque to ban television production because they were tired of being featured on it so often. So when Gov. Gary Johnson (whom most people know more for being the perennial Libertarian candidate than for the state he governed) started and Gov. Richardson finished the process of developing film incentive tax credits in the state, they had to do so by basically convincing Albuquerque to let go of its "city of crime on tv" bias.

The tax incentive program did nothing to help New Mexico be recognized by the rest of the US until Breaking Bad came along. Productions beforehand were more like "Albuquerque kinda looks like LA so that's some discount location shooting." Breaking Bad was the real breakout of "No this is a specific place with a specific character." Everyone now either thinks they know Albuquerque because they saw it on Breaking Bad, or they are humble enough to ask "Is it anything like Breaking Bad?"

Which, to give Breaking Bad a lot of credit, its location scouting is ... whoof... outstanding. Anywhere in that show where anything happens is more or less where that sort of thing would happen. It doesn't necessarily ACTUALLY happen, but if it did... yeah, that's... that's where that would happen. I caught that vibe when there was a scene in the Triple-K near what we call "Ghetto Smith's" where Jesse and Walter are trying to pretend not to know each other while talking over the junk food displays: yeah. I've been to that Triple-K. That happens there.

But, as one person once pointed out when I was telling him basically this exact same thing: "So, are you saying you'd rather be known as meth dealers than Mexican?"

I used to joke that Breaking Bad terribly misrepresented Albuquerque because everyone there is on heroin, not meth, but I'm tiring of the jokes in general and really wanting some solid Burqueño filmmaking about all the cool stuff there. I for one want to make a feature based off of some of Lucia Berlin's short stories from A Manual for Cleaning Ladies, but unfortunately I can't secure the rights to them (I'm under the impression that Cate Blanchett owns them). But the point is there is a ton of good story potential, not just in Albuquerque but the region, that deserves more than just leaving it to the Breaking Bad universe and moving on.

Oddly enough, Mr. Haddon, your pics of Detroit remind me of many parts of my own hometown, though a much smaller, anachronistically old and new city, Norfolk, VA. Elements of the very new, very old, beautiful and downright trashy exist right around the corner from each other...! This article has made me think more about the settings of my scripts, varied to say the least. Guess that's the point, right?! Much enjoyed the read - perhaps even more so the pics. Sure bends my perceptions of your hometown!