Q&A: Writer-Director Chris Weitz on What He's Learned from Growing Up (and Older) in Film

THE CREATOR scribe takes me on a tour through his family's long Hollywood history, the evolution of his craft, and the balance he's finally found as a filmmaker

“Do you think that’s the silent film actor Conrad Veidt, star of THE MAN WHO LAUGHS, standing next to your grandfather in the photo?”

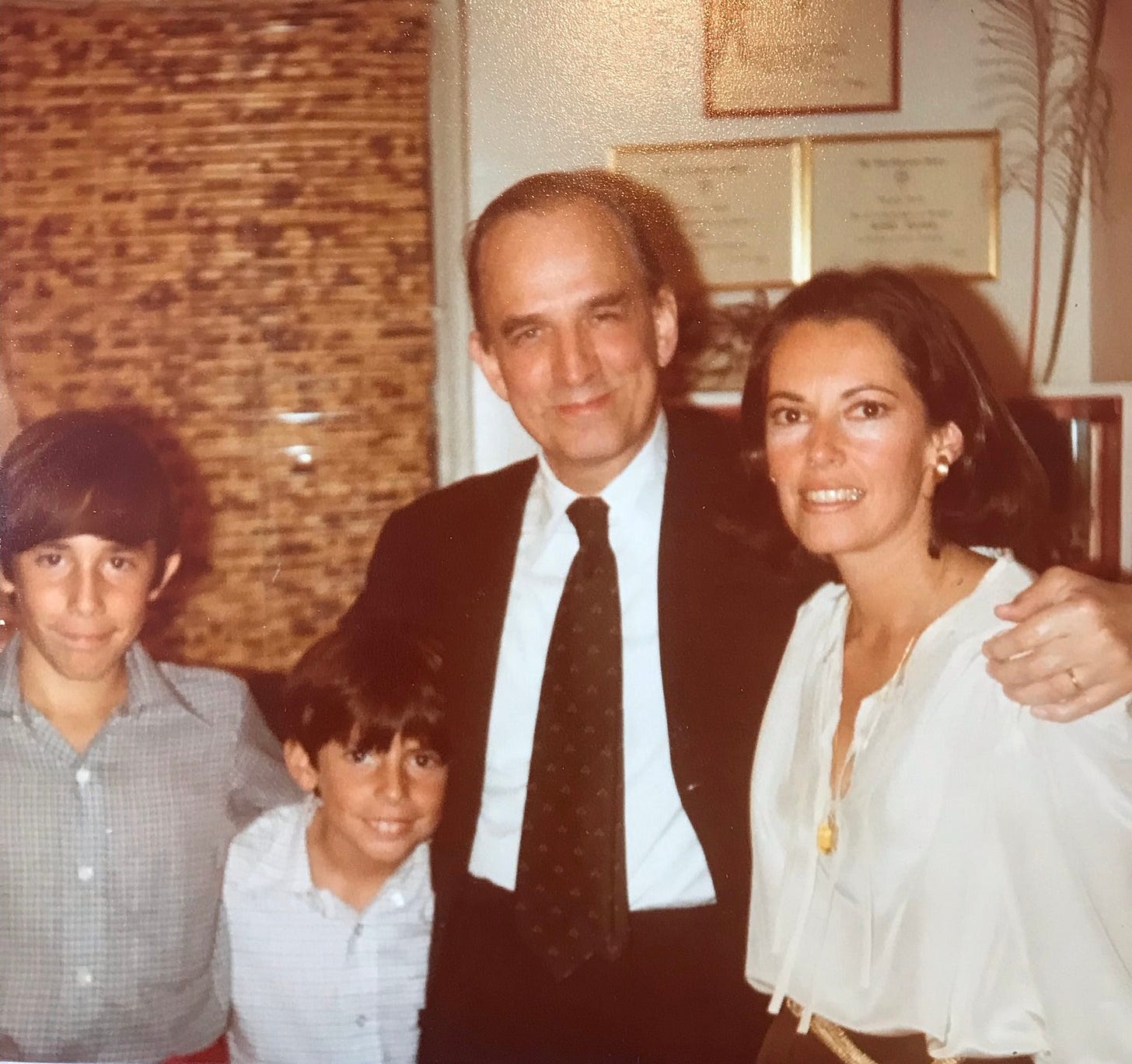

This is not kind of email I send every day, but, for a cinephile like me, it made my morning. The B&W photograph it was referring to was one of several that filmmaker Chris Weitz sent me to include in my latest artist-on-artist conversation, each a little piece of his family’s long history in Hollywood. This history goes back to the nineteen-twenties and includes an eclectic line-up of international characters ripped from a Wes Anderson film. It culminates — at least for now — with Chris and his brother Paul Weitz, who together broke into the movie business as screenwriters before directing AMERICAN PIE (1999) together. The high school sex comedy — which I adore, as you’ll read below — led to the pair writing and directing a handful of other pictures together, including ABOUT A BOY (2002), before they began working apart (they still run a company and produce together, including each other’s work).

Chris has intrigued me for many years now because he has been so successful at resisting being classified as this or that type of screenwriter or director. This is the guy who wrote ABOUT A BOY1, CINDERELLA (2015), and, most recently, THE CREATOR2 (2023) – three spectacularly different films in terms of genre, tone, and likely audiences. He’s also the guy who directed AMERICAN PIE, THE TWILIGHT SAGA: NEW MOON (2009), and A BETTER LIFE (2011) – again, three films that couldn’t be more different. As you’ll read, part of the reason for this variety is the creative DNA that his culturally diverse family provided him.

One more thing I feel it’s important to note: Chris doesn’t write every film he directs and he doesn’t direct every film he writes. This is much rarer than you might think, as, historically speaking, most screenwriters tend to leave screenwriting behind, at least for others, when they finally get the chance to direct. Not Chris, who actually has more credits in the second half of his career as only a writer than he does as a director.

What follows is a unique opportunity to learn about a filmmaker and his life through the lens of three generations of his family’s Hollywood story. The century-long creative odyssey comes with many lessons, as you’ll see.

COLE HADDON: Your career spans about a quarter-century now, which you’ve spent as either a screenwriter or director, but only a few occasions as both. What is your relationship to both crafts like these days?

CHRIS WEITZ: Yes, I am old. Wait, I’m not supposed to say that, because my axons and dendrites or something are listening and will decide to give up the game. In fact, I am very young and energetic. Let’s see. It’s actually more like thirty years doing this, but twenty-five years since my brother Paul and I first got official credit on something.

Directing a film — properly doing it — is a year of your life or more. It’s bound to take a physical and mental toll because — while it’s a position that benefits from a single “vision”, or whatever they’re calling it these day — it’s actually more work than one person should do. It’s not great for families. You’re away from your children physically and/or mentally quite a bit. I would rather be a decent father than a great director - this may be my downfall.

CH: Not given the way I measure life, my friend. You’re doing it right.

CW: Thanks, man. Well, in the past, my wife Mercedes and I would up and take the children to wherever I was shooting, Vancouver or Buenos Aires or wherever. But that was when the children were little. Uprooting them at this stage would be bad for them. I decided it would be better to shoot in Los Angeles if it were possible. So, the last film I directed, for Blumhouse, was set and shot in Los Angeles. The Blumhouse people are very cool and humane and were willing to back me in keeping it local, which was amazing.

Side note: the film got a California rebate on the budget, which was great, but it is still less than other locales offer, and it is a terrible shame that the center of the film industry is not where most of the films get made.

CH: You’re talking about THEY LISTEN, right?

CW: Yeah. I wrote the script myself, which helped. I felt as though I held the key to it.

CW (cont’d): I’ve enjoyed directing films written by other writers, or based on other people’s work, but this time it felt as though I needed to have been in on the ground floor. Even other stuff I’ve written and directed, like ABOUT A BOY or THE GOLDEN COMPASS, owed a debt to the writers whose books I was adapting - and I take that responsibility seriously.

The writer’s dream is to see her or his script brought to the screen with minimal fuckery on the part of other people with a “vision” for things. By directing, I’m taking out the middle man. Nobody to blame but myself, less guilt towards the original writer.

CH: How do you like writing for other directors?

CW: I love writing for other directors, too. And I like to think that they feel I’ve been in their shoes, so I will try to get them to where they need to be not just creatively and pragmatically. I’m much happier subsuming my identity when that happens. I’ve written on two movies for Gareth Edwards — [ROGUE ONE: A STAR WARS STORY and THE CREATOR] — and they’ve been his thing. What’s good about them is because of him — minus some Buddhist malarkey I keep trying to secret into them — and they make me happy. And I think, there is no fucking way that I want to direct that epic battle sequence in Thailand for THE CREATOR, and no way I could have equaled it if I did.

“The writer’s dream is to see her or his script brought to the screen with minimal fuckery on the part of other people with a ‘vision’ for things. By directing, I’m taking out the middle man.”

CH: Directing, as you say, is a monumental undertaking. The commitment consumes your life compared to screenwriting, which I’m assuming is part of why you aren’t as prolific as a director as you are as a writer – especially over the past decade or so. Being such a multi-hyphenate — because you also produce other people’s films, such as Lulu Wang’s THE FAREWELL that you know I love — do you have a core identity when you think of yourself? Are you, more holistically, a filmmaker in your mind, or are you, say, a screenwriter who happens to direct from time to time?

CW: I’d say I’m a kid who played D&D and loved eighteenth-century British novels and couldn’t figure out how to make that a career and then lucked into screenwriting, then got into directing in theory to protect my scripts, and who is still learning on the filmmaking front. Because I got lucky early on with the reception of some of my films, I was given a — probably limited — supply of pixie dust to sprinkle on some other people’s work. I know a good thing when I see it, so that’s how something like Lulu’s film happened. It was her thing and my colleagues and I were able to help it along.

CH: Let’s talk about how you ended up a storyteller at all - because I think it’s fair to say you were born into a family of them. Your mother is actress Susan Kohner, who gave one hell of a performance in IMITATION OF LIFE, for which she was even nominated for an Oscar. Your father John Weitz was a novelist amongst other talents. Your grandmother was Lupita Tovar, who starred in the Spanish-language version of the original DRACULA and she was married to Paul Kohner, a successful film producer until he became an even more successful talent agent. And, of course, your brother Paul is a screenwriter and director. Tell me, what was it like growing up in a family so steeped in the arts?

“You get to the last thirty minutes, and Max von Sydow shows up. Except, to me, ‘Uncle Max’ shows up.”

CW: In retrospect, it was weird, but as a kid you take everything as given. I had a strange experience of that the other day.

CH: How so?

CH: I was re-watching THE EXORCIST. [Its director] William Friedkin had just passed away and, also, I was thinking of the scary near-subliminal cut in the dream sequence in reference to THEY LISTEN, which I’ll be finishing when the strikes are over. So, people should watch THE EXORCIST if they can stomach it, it’s a truly shocking movie. I think the only contemporary moviemaker who can shock in this fashion is maybe Ari Aster. Maybe Gaspar Noé. Anyway. You get to the last thirty minutes, and Max von Sydow shows up. Except, to me, “Uncle Max” shows up.

CH: I hadn’t realized you two had a relationship.

CW: My grandfather was Max’s agent, so I knew Max and his family from childhood. I have very particular associations with him, his warmth and decency and kindness. So, Father Merrin’s appearance — I know, he’s in the first part in Iraq, as well, but by the time he gets to Georgetown the charge has diminished — hits me strangely. On the one hand, it increases the unreality. On the other hand, it makes it 100% more upsetting when Merrin is struggling and when he dies. There was a weird porousness, conceptually, between “normal life” and movies for me.

CH: What a lovely, surreal description. Haunting even.

CW: You’re kind. And then, vis a vis being steeped in the arts, my dad’s background was Weimar Berlin, British public school, Oxford, the works. He was a designer, and on the side wrote novels and also biographies of prominent Nazi party members. I was his research assistant – he used to send me to look for obscure German diplomatic histories at the Main Branch of the New York Public Library. So, it felt as though it would be entirely reasonable to have a career as a writer or put another way, as an artist - if that’s the word. It always feels weird to deploy it in this context, since I work in an industrial setting much of the time. A film set is an industrial setting to manufacture and capture pretend stuff. You try to make the process feel creative and artistic.

“Nobody was going to give me and my brother a job because our grandfather represented a bunch of guys with funny accents a million years ago. But the sense that it was something that people actually did made all the difference.”

CW (cont’d): On the other hand — the world of my mom and my dad and my grandparents was an old world — quite specifically, Central European. Most of the actors and writers and directors had strong accents. They referred to canonical cultural works, they were as out of contact with the movies as they were when I started writing. Nobody was going to give me and my brother a job because our grandfather represented a bunch of guys with funny accents a million years ago. But the sense that it was something that people actually did made all the difference. I’m very conscious that this was a privileged position. Paul and I worked really hard at it, but we were lucky in a hundred ways, and one of them is an accident of birth.

CH: I’m a Douglas Sirk fanatic, so IMITATION OF LIFE means a great deal to me, but the 1931 Spanish-language DRACULA played such a huge role in setting your family’s Hollywood story in motion. You and Paul are even adapting a memoir about your grandparents’ romance. Can you remember your reaction to seeing these two films for the first time?

CW: Let’s see. With IMITATION OF LIFE, I guess it was like that thing with Uncle Max that I mentioned. I was a kid, and the mom in the movie was a younger version of the person I knew. At first, it was very, very strange to see her in a movie, and needless to say, it affected the way I received the film. But all the same, I cried at the end as though the obvious impediment to the suspension of disbelief wasn’t a problem. Interestingly, my mom was often cast in “ethnic” roles. Biracial in IMITATION, an Arabian princess in THE BIG FISHERMAN, Native American in THE LAST WAGON. She was half-Mexican - that’s the entirety of her genealogical qualifications to play those roles. But that relatively small distinction was enough to make her seem different in the Hollywood of that time. Her mom was Lupita Tovar, who was scouted in Mexico by Robert Flaherty - director of the documentary NANOOK OF THE NORTH. It was a sort of PR stunt. He was sent to find “the most beautiful girl in Mexico” and put her under contract for Fox. She came to Los Angeles with her grandmother as her chaperone and started working in silent films.

CH: How did DRACULA happen then?

CW: The Spanish version of DRACULA is the result of my grandfather’s convincing Carl Laemmle at Universal to re-use the sets of English language movies to shoot foreign language versions. So, my grandma would start shooting in the same sets as the Bela Lugosi version, but from midnight onwards, through the night. There are partisans who prefer the Spanish language version. One way or another, it’s an interesting angle on Mexican Los Angeles, immigrant America, and Hollywood. To make the whole thing even more meta, we’re doing the film with our uncle Pancho as producer. I remember seeing the restored version of the Spanish DRACULA for the first time at the Dallas Film Festival – someone had found a missing reel in Cuba and it was possible to see the entire cut.

CH: What was that like?

CW: I guess my impression — I was already making films by then — was the continuity of the job of making films from the nineteen-twenties and nineteen-thirties to the, then, nineteen-nineties. On the surface of it, the industry had changed entirely. But really, people were still just playing pretend and capturing it to replay, same as before. The other thing — which is maybe a bit of an abstruse point — was the variety of the Spanish-speaking world. My mother was Mexican, Dracula was played by a Spaniard, and the love interest was an Argentinian guy with the unlikely name of Barry Norton.

“I don’t think that I would have had the guts to do it if we hadn’t been working together.”

CH: Okay, so you come from this spectacularly artistic, incredibly international family – I haven’t mentioned yet for readers your family also includes German émigrés fleeing Nazi Germany. Mexican, German, Jewish, pretty much an all-American mélange as a result. Was it challenging at all to develop your own creative identity within a family such as yours?